Frank Gehry photographed by Buck Ellison for PIN–UP 30.

Frank Gehry photographed by Buck Ellison for PIN–UP 30.

Frank Gehry is arguably the world’s most famous living architect. At 92, does he even require an introduction? Pritzker Prize winner. Iconoclast. Angeleno. His buildings are sculptural and controversial — cultural flash points and crowd-pleasing favorites. Last year, Frank Gehry: Catalogue Raisonné of the Drawings Volume One, 1954–1978, edited by historian Jean-Louis Cohen, was released by Cahiers d’Art. The first of what will be eight career-spanning tomes, the book focuses on early works — designs that predate the titanium and computational dexterity that mark Gehry Partners’ best-known architecture. The 1950s through the 70s were a time of wild growth and experimentation for the architect, from his diploma thesis at the University of Southern California (1954), with its midcentury aesthetic akin to the Case Study Houses and rife with Japanese influences, to Gehry’s own residence in Santa Monica (1978), which exploded any conventional notions of home. The abundant sketches and drawings in the Catalogue Raisonné reinforce an understanding of Gehry as a processes-based architect: iterative and intuitive, rigorously searching for form in what others might see as the arbitrary — methods, perhaps, not dissimilar to those practiced by the cohort of East and West Coast artists he ran with at the time.

PIN–UP sat down with Gehry on a Zoom call just shy of a year after the publication of the Catalogue Raisonné to discuss the archival works. Our conversation lingered a bit in the past, skirting delicately around old beefs and hijinks. Inevitably, it surged forward and leaped over icons like the Guggenheim Bilbao (1997) or the Fondation Louis Vuitton (2014) to reckon with a contentious project in Gehry’s home-town that may rewrite his legacy in Los Angeles.

Portrait of Frank Gehry photographed by Buck Ellison for PIN–UP 30.

Mimi Zeiger: Hi Frank. The first volume of your Catalogue Raisonné was published last year and covers the mid-1950s through the 1970s. What does it mean for you to look back on your career through your archive, the drawings, and the collection of works that Jean-Louis Cohen selected for this volume?

Frank Gehry: I’m not very good at looking back. Some of the things I am proud of and some of the things I have worries about. I don’t want to go back in time, soI just go forward. I’ve known Jean-Louis for a longtime. He knows me as a person, and I trust his judgment. The idea of a catalogue raisonné is to develop it for future generations who are interested in my work — as a teaching tool, as something to look at, argue about, and discuss, be inspired by, or the reverse…

What would be the reverse?

That they don’t like it. The context of some of the work goes with a different politics than we have now.

You say you don’t like to look back, but the archive is pretty meticulous. You kept everything — it’s one of the largest collections at the Getty. Did you always plan to leave an archive as a legacy?

No, not at all. As it grew, I had a couple of exhibitions, but the one that turned me around was at the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art in Denmark [Frank O. Gehry: The Architect’s Studio, 1998]. That show really opened my eyes, because they took one project that wasn’t necessarily my greatest ever — a business school. Not something I would want to show everybody when I exhibit what I do, but we had worked really hard on it. The curator filled a room with all of our models. Every evolution. If you walked into that room and thought about making each one, it was like watching paint dry. Each one moved slightly. We’d finish a model, not like it, move on to another one. I had the team rebuild another one and another one and another one. Those 40, 50 models happened over a couple of weeks, not years. I wasn’t even aware of what I was doing, that there was that kind of precision in the search that I was going through for that building. I don’t think I completely succeeded. Parts of the interior are much better than the exterior, but it showed me that I had to look at myself. I understood it would be interesting to some architecture students to know my way of thinking out loud — thinking visually rather than talking about it, rather than having a philosophy. I came on the scene with the Whites, the Silvers, and the Grays and what not [the Whites, who shared an interest in Le Corbusier, were Peter Eisenman, Michael Graves, Charles Gwathmey, John Hejduk, and Richard Meier; the Grays, who aligned themselves against the International Style, were Charles Moore, Jaquelin Robertson, Robert Venturi, and Richard Weinstein; the Silvers — Craig Hodgetts and César Pelli — were into high-tech]. Everyone had a philosophy, and they would sit and talk about it. They brought in arguments from classical thinkers and people like that. But it didn’t address the issues I was interested in, so it was kind of like noise. I loved reading it, but it was peripheral — like going to a concert or lecture. Interesting, but it didn’t resonate with me.

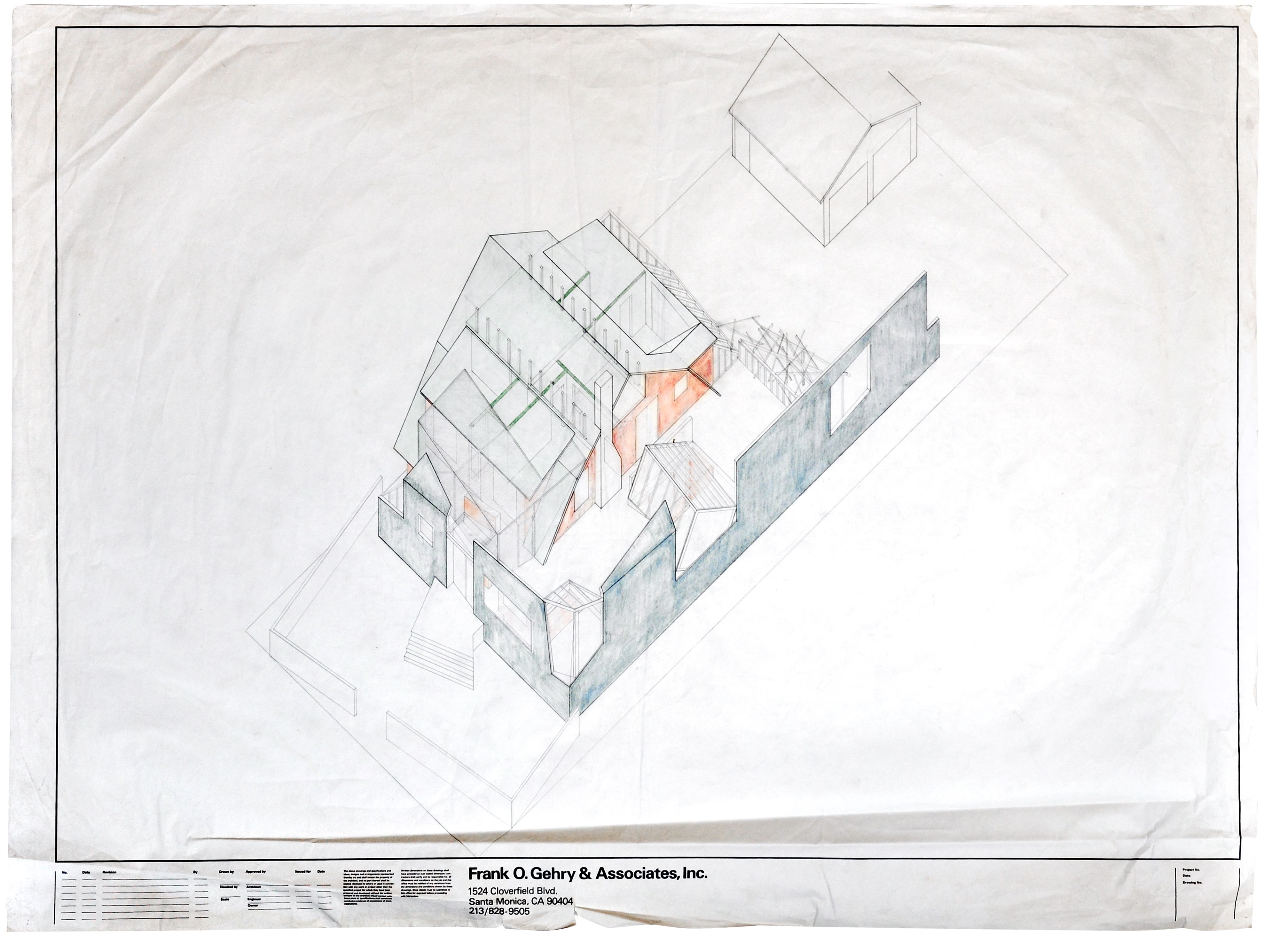

An axonometric drawing of the famous Gehry Residence in Santa Monica. In the early 1990s, the Gehrys would expand the home further to make space for the changing needs of the family. Whereas the original 1978 addition incensed neighbors, the new revisions upset Deconstructivism purists who felt the house now looked too “finished.” Gehry never considered the house part of the Deconstructivist movement, despite being included in a 1988 MoMA survey show curated by Philip Johnson. Sketch © Frank O. Gehry. Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles (2017.M.66), Frank Gehry Papers.

Did you ever think of yourself as an artist?

I took night classes in art at the University of Southern California. I was a truck driver, so I couldn’t go full time. I remember taking an art history class that opened a lot of doors in my thinking. There were a lot of professors who were working artists, and the school of architecture shared the building with the art school. When I got into the architecture school, one of the first things I started doing was trying to connect the artists with the architects and have events, but I could never make it work. It just seemed impossible.You would run into them all the time in the corridor and they didn’t talk to each other.

You’ve spoken about how you prefer to hang out with artists rather than architects — folks like Larry Bell or Ed Moses.

That is probably in my DNA, but it was also circumstantial. When I came out of school and started to work, the art scene was really hot. LaCienega Boulevard every night. I’d go to Monday night art soirées. I met a lot of people, and I loved it. The architecture world at the time wasn’t interested in me or what I was doing. I wasn’t upset by it — I wasn’t connecting with those people. Richard Meier was doing white buildings, and everybody loved that. There was a barrage of philosophy that had nothing to do with what I was interested in at the time. The artists were more intuitive. They came to see my buildings under construction. I didn’t invite them, they just found them. Ed Moses invited me to the club. He was very important in my life. He brought me right into the art scene — the social life, the ateliers, drinking. I went to their studios, I watched them work. I felt comfortable watching Bob Irwin struggle with his dot paintings. I could connect with those artists and through them I met John Chamberlain, Jasper Johns, and Robert Rauschenberg. That fit my psyche better, I must say.

Chamberlain, Johns, and Rauchenberg were all East Coast artists. Tell me a bit about your relationship with that New York scene, especially since the 60s and 70s overlap with the body of work in the Catalogue Raisonné.

I was going to the East Coast a lot with my friends. I was hanging out at a bar and I met John Chamberlain, who became a really good friend. We had a really good time with John. Through him I met Warhol. I went to the... What was the name of his place?

The Factory.

Yes. We met Viva and Ultra Violet, who was John Chamberlain’s girlfriend at the time. I don’t know what they were smoking — they were on some drugs that I didn’t get into. Whenever I was in New York, I spent hours in Bob Rauschenberg’s studio. He would invite me over very late in the evening after dinner. He worked from maybe 10:00 in the evening till 4:00 in the morning on his paintings. And I would sit there with him while he was working and talk.

Portrait of Frank Gehry photographed by Buck Ellison for PIN–UP 30.

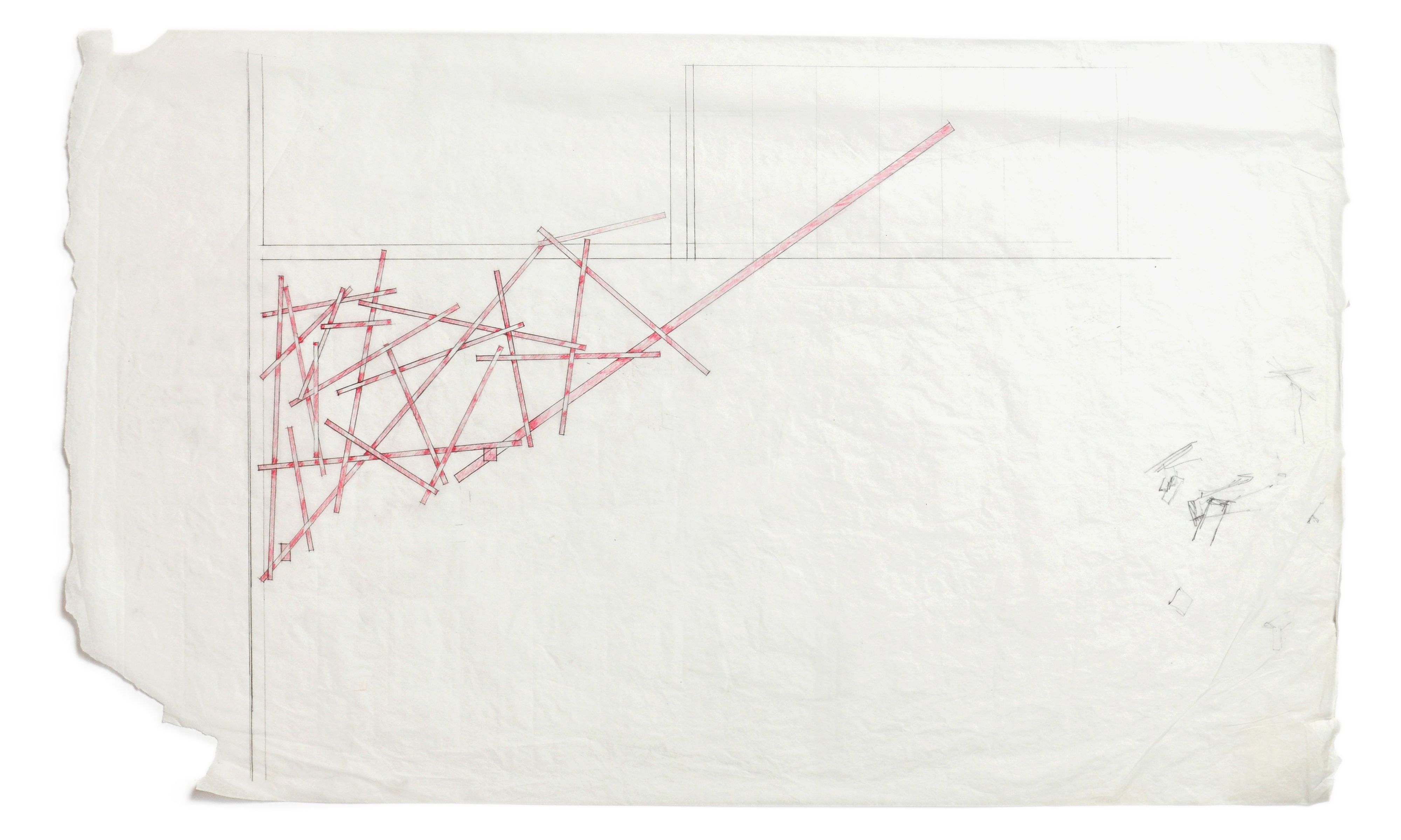

Frank Gehry’s 1968–72 Malibu residence and studio for painter Ronald Davis exemplified his early personal style of using accessible materials to sculptural ends — in this case galvanized steel and plywood. The interior of the trapezoidal structure was divided into open intersecting volumes. Sited against a stark, hilly landscape, the home was among the 1,643 structures destroyed in the 2018 Woolsey Fire. Sketch © Frank O. Gehry. Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles (2017.M.66), Frank Gehry Papers.

And what about the New York architects at that time, like Philip Johnson, who championed your work?

That happened separately. I was really involved with the artists and I didn’t particularly pursue Philip Johnson or anybody. That was off in the distance. I was, however, working with Christophe de Menil on her house. She was a friend of Philip’s, of course, because her mother had worked with him in Texas. So inevitably there was talk of Philip. He came to L.A. and wanted to see the Ron Davis house [Gehry’s 1972 Davis Studio and Residence in Malibu is sometimes called the Tin House because it is entirely clad in corrugated metal]. Ron and I both got scared and smoked a joint and we don’t remember whether he was there or not. After, Philip invited me to come to the Glass House. I would say he was mildly interested in my work — he kept tabs on me. In terms of Peter Eisenman, Richard Meier, and all those people… that was very peripheral. I was introduced to Eisenman through an art connection, whose wife was a major donor to the New York City Library. I joined the board of the Institute for Architecture and Urban Studies, but I was always living these two lives. My real world was the art world. My second world was maybe Eisenman and those guys. I would go to things with them, but I was kind of the outsider.

The last project in this first volume of the Catalogue Raisonné is your own home in Santa Monica, the Frank and Berta Gehry Residence, from 1978. There are more than two dozen pages dedicated to photographs, sketches, and drawings. Could you talk a little bit about the house’s design?

My wife Berta found the house and, at my mother’s urging, bought it. I had to fix it. We had two little kids and not much money. We needed to do something quickly — it didn’t have a large enough kitchen; it didn’t have a bedroom for the second child. I was interested in simple materials — you didn’t have to get fancy materials. I worked with corrugated metal, which I liked galvanized. I didn’t like the way it was typically used, but I liked the aesthetic. And I loved wood, of course, from the Japanese-influenced stuff to wood framing. We had a 12-foot side yard that we could build on. So, I said, “Great. Why don’t we just build a new addition on the side?” That became a foil against the old house — you kind of see the old house against the new construction. From the inside, I was interested in looking up and out rather than sideways, because the neighborhood wasn’t thrilling in terms of architecture. But from the rooftop you could actually see the ocean, you could see the airport. I played with all of those things. That’s why the windows were made the way they are. They take advantage of the large trees on the street and they play with the light. I was also working with the movement of the moon across the sky. You could see it from time to time at different points in the skylights. We would get a lot of reflections on the ceilings and skylights, light bouncing off cars in the street. There was a kind of kinetic lightshow going on, which you could look at or not — it wasn’t an imposition as much as it was just there. We spent 50,000 dollars, which is a very small sum with respect to the whole house. The neighbors got really pissed off. One neighbor from across the street came over and said, “Why did you do this to our neighborhood?” I said, “Where do you live?” He showed me and I said, “Look, your backyard has a trailer. That trailer is made of metal and it’s not very pretty. It’s sitting there, we’re looking at it. Your front lawn has some old car up on blocks. I think I’m just doing what you’re doing.”

How did he react?

Yeah, he had to think about it. He didn’t quite get it, but he didn’t make trouble. The neighbor two doors south of me was a lawyer. She complained to the city and filed a lawsuit and stuff, but she didn’t get anywhere. Finally, she remodeled her house. And guess what she did? She built a new house around her old house. It doesn’t look exactly the same, but she copied my idea.

Frank Gehry photographed by Buck Ellison for PIN–UP 30.

Frank Gehry photographed by Buck Ellison for PIN–UP 30.

Frank Gehry photographed by Buck Ellison for PIN–UP 30.

I’d like to jump forward in time and talk about the big project Gehry Partners is working on right now: the L.A. River. The latest scheme proposes elevated platform parks spanning portions of the river and a 150-million-dollar cultural center. This project’s ambitions are a far cry from your early career working for Victor Gruen. It could be said that his legacy is the American shopping mall. Is the L.A. River yours?

The office is doing great. I have a lot of freedom to explore things that I’m interested in. Los Angeles is where I live, but I had never really been interested in the river. I knew it was there, I drove across it every once in a while. It was concrete and it was whatever. I knew some people liked the concrete, others didn’t. I didn’t think much of it, other than it was a flood-control project and nobody wanted to do much with it. Then, a few years ago, I got a call from two gentlemen from the movie industry who said they were friends with Mayor Garcetti and that they were interested in a recently completed project in New York City called the High Line. They thought it was spectacular that it was not only financially a great success but also a resounding success from a people’s standpoint. They said, “Here we are in Los Angeles with 51 miles of river that connects all kinds of neighborhoods. Would it be possible for Frank Gehry to show us how to build a visual image that would brand the L.A. River?” They were thinking of a graphic program, a landscape program with tall trees, toilet facilities, food kiosks, and so on. They wanted me to develop an image for the 51 miles that would be easily assimilated and make the L.A. River do for Los Angeles what the High Line did for New York. I looked at them and said, “You guys are crazy.” The High Line was a rusty old railway that was about to be torn down. The L.A. River was a flood-control project, which has a different mandate. I said, “I don’t think it could do what the High Line did, but let me look at it.” We did a two-year study, during which we examined everything about the neighborhoods the river went through: the economics, the health issues, what that river did, what its ups and downs were, was it safe, and could you plant. There were some parts of the river where there was already planting on the bottom — it seemed beautiful. Maybe if it was already happening you could do it along the whole river? But the statistics led you to funny conclusions. The river is benign 98 percent of the time. The high flow — the big flood — happens two percent of the time. You say, “Two percent of the time, we ought to be able to handle that!” But guess what — you can’t. When that two percent of the time, which I call Godzilla, comes along, it wipes out everything you do. In neighborhoods like Atwater Village, where there is a soft bottom, you see bicycles in the trees after a storm. The only way to handle the water when it comes through is to find ways to divert it into a holding basin. That holding basin is a lot of land .If you go to these neighborhoods, people are living tight against each other with no open space. If you acquire some of that land for a holding basin, you’re displacing people. Talk about screwing up.

With his personal home, Gehry also laid the groundwork for his working style which famously involves many rapidly dispatched drawings like this one. “I got tons of sketches from him. It was the most kamikaze stuff,” recalls architect Paul Lubowicki, who worked on the project as a 23-year-old. When he showed Gehry the model he’d made based off an initial elevation sketch, Gehry took a knife to the maquette’s entrance. Sketch © Frank O. Gehry. Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles (2017.M.66), Frank Gehry Papers.

Your involvement in the L.A. River has been controversial. There are groups who have worked for years to figure out how to create a riparian landscape along its length.

The people who are still fighting us — I’m the bad guy now — are saying, “He’s trying to put in more concrete,” while they are trying to take it out. I would love to take the concrete out, but we still don’t have a way to divert the water. The only way to do that is to put the water in a channel, like a sewer channel, a big tunnel where the water can go two percent of the time. The cost of that is crazy. After meeting people around world who have done something similar, the way that seemed the most possible was to cover the river in places where you need park space. Which is South L.A. — South Gate, Compton, Bell Gardens, and other communities along the river.

What do you say to the concerns raised about balancing the need for green space in these communities with the fear of gentrification and speculative development that might ensue in those neighborhoods?

We spent a lot of time meeting with communities in South L.A. and talking about open space. We were told that children growing up in these areas have a ten-year-shorter life span. We checked that statement and it was true. We checked the economics, the average income of the people living there. We have done a really thorough analysis and there is a desperate need for low-cost housing, for housing for the homeless, for open space, and for culture. Our idea was to create a park on a platform over the river. I think we should try it at South Gate. There’s potential at the intersection of the Rio Hondo and the L.A. River to create 40 acres of green space within walking distance of many of those communities without displacing anyone. With the county, we are looking at ways we can create low-cost housing in some of these places. It’s a work in progress, we understand the issues. We’re very concerned about gentrification — we’re going do our best to make sure that doesn’t happen. It is a core value of our study and our work. This is a major social-justice project.

It’s also a decade-long project. You may retire before it’s finished…

Well, I’ll be 92 in a few days, so I don’t even know if I’ll be here. I do have a lot of well-trained architects who I am sure will stay on. My son, Sam, is a part of the firm and Meaghan Lloyd [chief of staff and partner at Gehry Partners] knows what to do. We have the same values.

Frank Gehry photographed by Buck Ellison on the cover of PIN–UP 30.