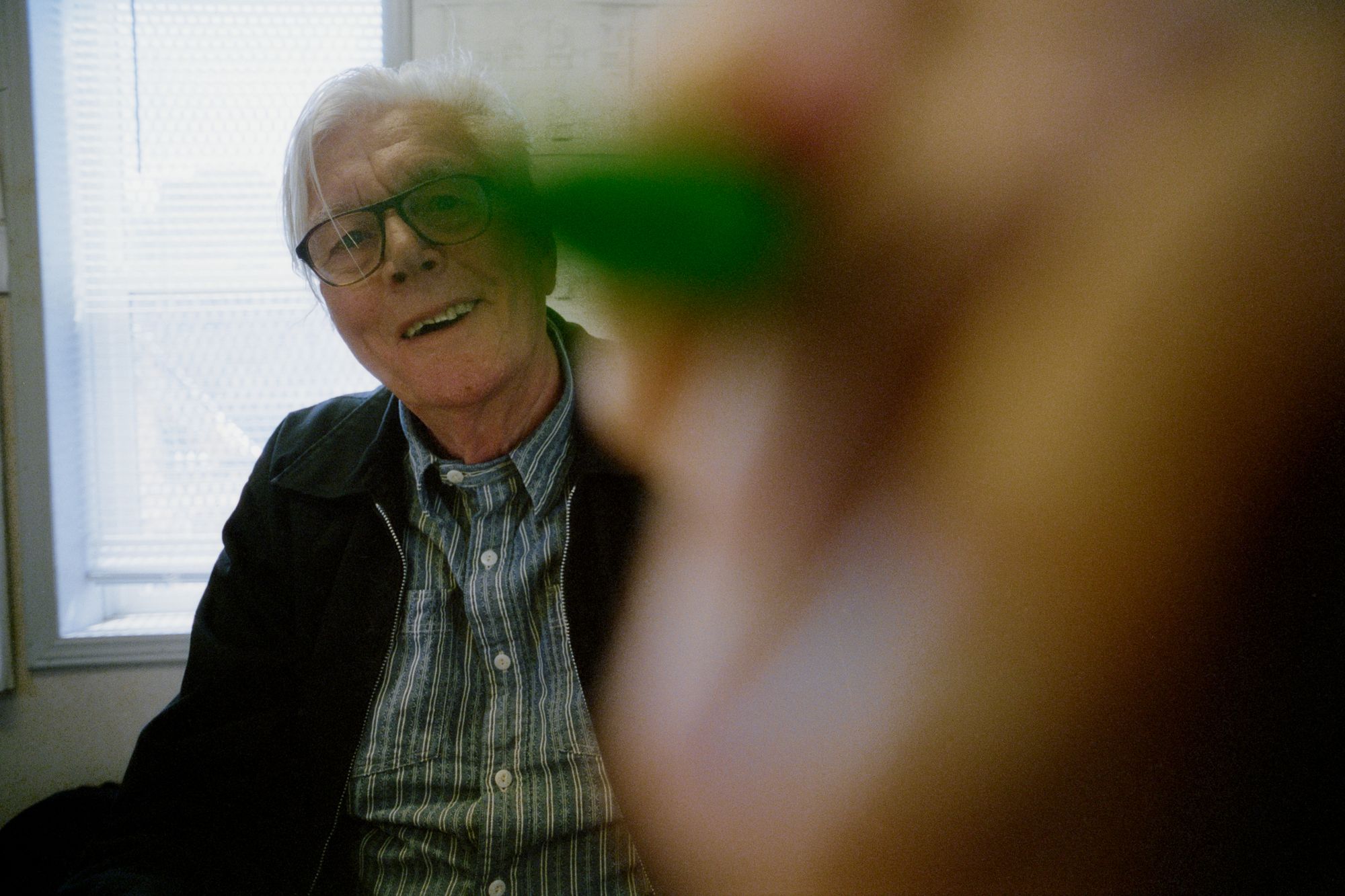

Portrait by Michael Cukr for PIN–UP.

Piet Oudolf on the site at the in-progress Calder Gardens in Philadelphia, a landscape he designed. Portrait by Michael Cukr for PIN–UP.

When Piet Oudolf wakes in the morning and the light is right, he reaches for a camera to capture his garden. The “garden” in question is the three acres he has been cultivating since 1982, the year he and his wife, Anja, bought an abandoned farm in Hummelo, in the eastern Netherlands. It is home to what many consider the holy grail of the new perennial movement. Perennials, of course, is the term for grasses and shrubs, and other plants that — unlike one-season annuals — die back and return year after year. To call Oudolf a landscape designer is correct, but it doesn’t capture the full impact he has had on horticulture over the past 40 years. Not only has he written over a dozen books translated into at least 8 languages, but through his dedication and experimentation on the estate in Hummelo, he has tested hundreds of species — from grasses to trees and shrubs — and developed many new cultivars. In his own garden, you’ll see echinacea, Molinia grasses, burnet, and astilbe — washes of earthy colors creating a shifting, year-round study in shape and structure. Though his works look lush, he emphasizes that nothing you see is wild; gardens, he says, are a “longing for nature,” or an enhanced version of it. His designs are based on meticulous planning with grid-like precision, mapped in color-coded diagrams that, beyond their practical use, stand on their own as works of art. A single project can involve more than 200 species and tens of thousands of plants, which he layers to mimic natural botanical communities. Oudolf’s bump from local hero to international landscape star happened gradually, though arguably New York’s 2009 High Line, a collaboration with Field Operations and Diller Scofidio + Renfro, is the job that made him a household name. Other notable projects include the Gardens of Remembrance in New York’s Battery Park (2003), the Lurie Garden in Chicago’s Millennium Park (2004), the ephemeral garden at Peter Zumthor’s 2011 Serpentine Pavilion in London, Oudolf Field for the art gallery Hauser & Wirth in Somerset, England (2014), and the Oudolf Garden Detroit in Belle Isle Park (2021). His most recent stateside commission is Calder Gardens in Philadelphia, where, alongside a new building by Herzog & de Meuron, he has brought his perennial touch to evolving plantings that frame the late Alexander Calder’s sculptures throughout the seasons. PIN–UP’s Felix Burrichter met with the 81-year-old to discuss garden clubs, getting used to being called an artist, and why his least favorite plant is bamboo.

Oudolf’s garden in Hummelo, the Netherlands, that he has been cultivating with his wife, Anja, for more than 40 years. Courtesy of Piet Oudolf.

Felix Burrichter: The official Piet Oudolf story begins in 1982, when you moved to your country property in Hummelo. At the time you were 38 years old. I would love to know a little bit more about your life before then.

Piet Oudolf: I grew up in western Holland, near the coast, where my parents owned a restaurant next to a nature reserve. I helped out on weekends, and the plan was for me to take over the business with my brother. But, in my 20s, I realized it wasn’t the life I wanted. I wasn’t happy. I took a temporary job at a garden center over Christmas, and they offered me more work after seeing my interest in plants. That’s when I bought a book on botany, because I noticed the staff didn’t know much. I also decided to go back to school to become a certified garden contractor and started my own business, building gardens. After five years, I realized that this world was too small for me, too prescriptive. I became more and more obsessed with plants during that time — obsessed in a healthy way — and wanted to grow them. I realized I could only truly learn about them if we had more space and grew them ourselves. So, in 1982, my wife and I bought a derelict farmhouse in Hummelo, near the German border. To fund the purchase, we sold our home and also took out a mortgage. It was one of those dreams you have but aren’t sure how to make a reality, but we had to make it work. We needed to survive — we had two small children. That’s when we built up a nursery in Hummelo.

Does your wife Anja also have a background in plants?

She was a nurse when we met.

She went from nurse to nursery!

Yes, both involve growing and caretaking. But most importantly, she’s been my partner, always having my back and taking care of the family. I couldn’t have done any of it on my own. She also handles the PR and deals with clients. The first three years in Hummelo were tough — we lived with very little as we worked to grow the business. In the beginning, I wasn’t designing anymore: we were solely focused on growing plants. I started collecting plants from all over — Germany, Scandinavia, England — and the variety attracted many people with gardens. Where we lived, near Arnhem, there were many garden clubs, and they would come to visit.

Portrait by Michael Cukr for PIN–UP.

Portrait by Michael Cukr for PIN–UP.

What are garden clubs?

These were people, mostly women, who would garden, travel, and share the experience together. It was a big trend in the 80s, especially in England, but also in Holland and Germany. They would visit English gardens, and when they returned, they realized we had the same plants they had seen there. That’s when we became a destination for garden clubs. They wrote about us, which attracted more visitors — including people from England — because we had plants from Scandinavia and Germany that nobody else had. Meanwhile, we were also focused on creating our own garden in Hummelo, as an example for people to look at.

What was your inspiration for your own garden?

By that point, I had read countless books on garden design, but I still couldn’t grasp how it was done. [Laughs.] Everything I did was intuitive. I wanted to arrange plants in a way that made people appreciate the beauty of the overall composition, not just the beauty of an individual plant.

Can you give me an example of what kind of plants you were interested in?

We had a variety of over 1,100 plants, but what intrigued me most were grasses and perennials — plants that bloom in the spring, summer, and fall, die back in the fall and winter, and regrow the following spring. The initial interest came about because on special days we invited small nurseries from the Netherlands to visit our property and sell their plants. Through this, we also met people from the wild-native-plant movement, who had a completely different perspective on plants than we did. It was fascinating, because they taught me that a plant could be beautiful even after it had finished flowering, or before it bloomed, or simply when it first sprouted from the ground. Our focus had mostly been on the decorative arrangement of plants, but, by learning from them, I began to appreciate the beauty of plants at every stage of their life cycle. The seedheads, in particular, became important to me. I started seeking plants with multiple characteristics, which ultimately became the foundation of my garden design.

In 1990, you published your first book, Dream Plants: A New Generation of Garden Plants. Was that in English already, or only in Dutch?

At the time, it was only available in Dutch. But someone from a university in southern Sweden saw it in a bookstore in Amsterdam, took it back to Sweden, and translated it into Swedish! That’s how people in Sweden became aware of our work. We started receiving invitations to conferences, and gradually the scope of what we were doing and our audiences grew wider and wider. But I never felt that this was about myself as a person. I just felt I could do something with plants that other people couldn't, and I wanted to share it.

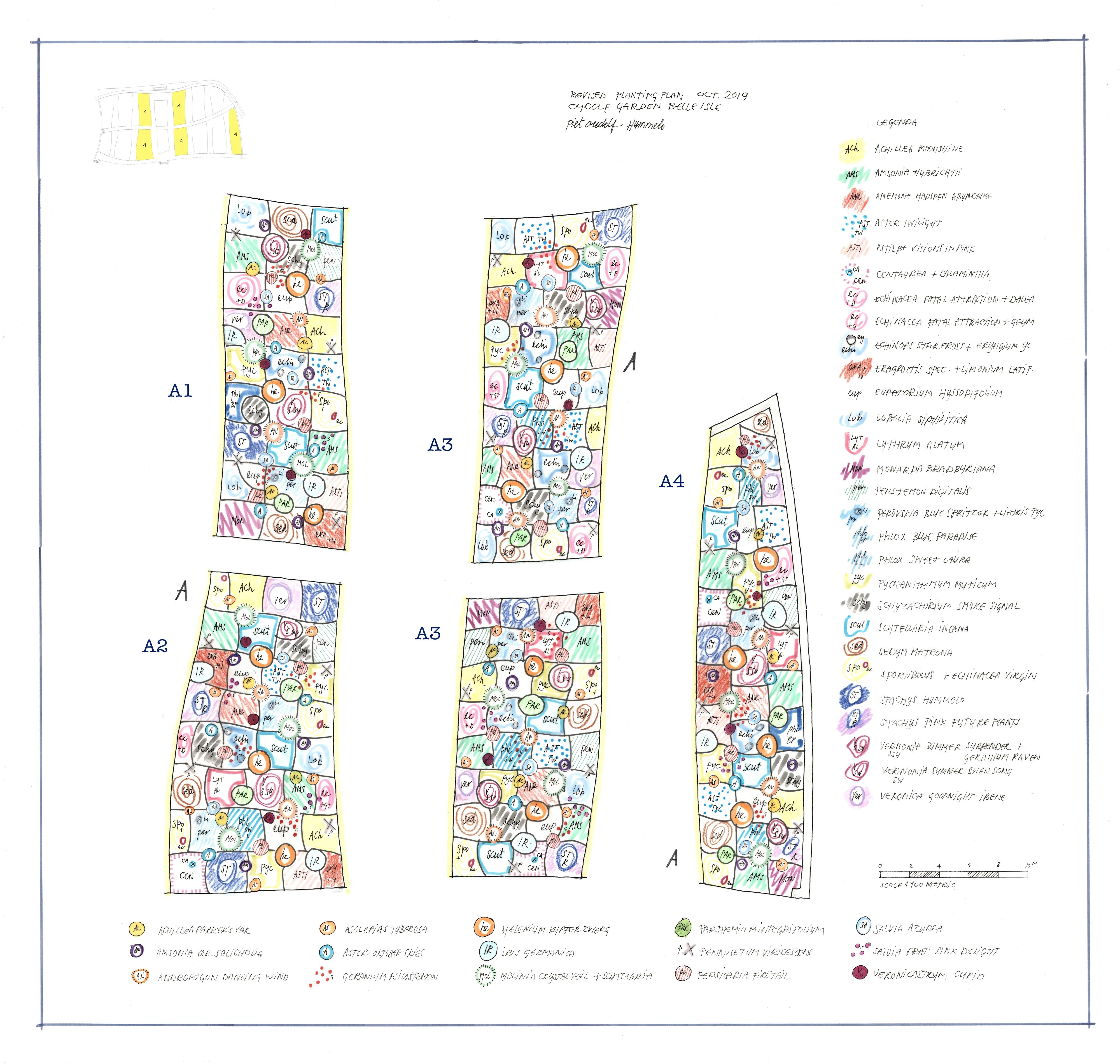

Oudolf’s revised planting plan for Belle Isle (2021), a three-acre garden in Detroit that features more than 160 varieties of perennials, grasses, shrubs, and trees. For his gardens to appear wild, meticulous planning is required, which he works out in colorful drawings that map the sequence of plants — the colors mark structure, height, and timing rather than the hues of the blooms themselves.

A lot of times people call you an artist, which I would too. You’ve refused the term in the past, but over time you’ve reluctantly accepted it.

That’s true. I created a signature that nobody can copy, so in that sense, it’s accurate. The reason I rejected the idea is that I’ve always thought of being an artist as creating work first and then selling it. But I always need a client first.

So who was your first client?

My very first client was a private couple near Haarlem, back when I was just building gardens. Then, after we moved to Hummelo, people from the nursery started asking us to design parts of their gardens, usually inspired by what I had created at home. Later, in 1996, we received a request from a small town in Sweden, Enköping, to design a public project called Drömparken [Dream Park]. It was my first public commission, and it became quite famous, which in turn made me well-known in Sweden. From then on, things happened quite naturally. That same year I also designed my first garden in England for my friend John Coke [Bury Court, Surrey], a well-known English gardener. He inherited a family estate, and we did a great job, which became a major advertisement for us. In 2000, I was asked to participate in the Chelsea Flower Show, the biggest flower show in the world, where we won the “best in show” prize. After that, I just kept designing one garden after another — as many as I could, because I always work alone. I don’t have assistants or anyone else in the office, aside from my wife.

When did you start getting commissioned for work in the U.S.?

The first was at Battery Park in New York City, and then we entered the competition for the Lurie Garden in Chicago [with Gustafson Guthrie Nichol and Robert Israel]. What’s interesting is that, through these public projects, I learned that plants are far more important to ordinary people, to non-architects, than architecture. Not that architects aren’t ordinary people, but I’m referring to the general public’s appreciation. Architects, on the other hand, tend to see themselves as the center of everything — they want the building to stand out. That’s changed over time. Today, architects are very happy if I can help them place their building in an environment of plants. But in general, I feel architects miss something — they can’t quite perceive the mystical element of plants.

Oudolf Garden Detroit on Belle Isle. Courtesy Piet Oudolf.

Portrait by Michael Cukr for PIN–UP.

Portrait by Michael Cukr for PIN–UP.

In a way, the goals of architecture and landscape design are diametrically opposed. Architects always aim to build something that withstands the test of time, while your work is designed to evolve and grow with time.

Yes, when my work is finished, it’s not the end — it’s just the beginning. When I think about plantings, I have to consider the next ten years minimum. For example, how big will this tree grow? You don’t want to lose beautiful plants because they’re too close to a tree that will stress them out as it matures. My thinking is four dimensional.

Can you let go? Or do you show up unannounced and say, “Hey, what happened here?”

I can’t keep up with every garden I’ve designed. If I had to visit them all, I wouldn’t be able to work anymore. Sometimes, when I’m in the neighborhood, I’ll check one out. But if it’s not in good shape, I usually don’t go back. I’ve seen gardens degrade in one or two years because people don’t understand that maintaining them requires someone with knowledge. So, I have to let that go — I’ve done it many times. However, I love returning to the Lurie Garden and, of course, to the High Line. I’ll come back after a couple of years, walk around with the gardeners, and I never stick to the original plan. We see the garden as a process.

Do you try to use only an indigenous plant palette, or do you mix indigenous and non-native plants?

We work with a variety of plants that complement each other, but we’re not trying to create nature. We’re creating gardens. Sometimes the plants come from the same biotope, but other times they come from different countries or regions of the world. In the U.S., for example, we can easily use 70% natives and 30% non-natives, chosen to contribute to the garden in different seasons, attract insects, and so on.

Which brings me to the point about the difference between flora and fauna — how much does the fauna aspect influence your process?

Yeah, there are always things you don’t really want as a gardener like mice and rats, deer, rabbits, hares, etc. You can find a good balance in that, you know, you don’t have to put poison down everywhere. We try to work with very healthy plants that don’t have diseases. Otherwise we don’t use them. We don’t spray plants, we don’t use herbicides. We don’t use insecticides. So we keep it healthy.

The new Calder Gardens, Piet Oudolf’s most recent U.S. project. At the heart of the triangular lot, Herzog & de Meuron’s reflective Calder Foundation pavilion mirrors Oudolf’s planting design, blending seamlessly into the surrounding vegetation. Photography by Iwan Baan. Artwork: Alexander Calder © 2025 Calder Foundation, New York / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

In your books, you make extensive lists of plants that explain how to use them best, what their attributes are, etc. Are there any plants that are blacklisted in the world of Piet Oudolf?

In our gardens we avoid aggressive plants like bamboo. Or Japanese knotweed. That’s one of the most aggressive plants in public areas. Some grasses can be very aggressive too. We made all the mistakes. But we learned our lesson, and in the end you don’t need them. Why use them if you don’t need them?

What if a client says, “I want a bamboo garden!”

I wouldn’t do it. Because a bamboo garden needs scale, and I haven’t designed gardens that were big enough to let bamboo grow without constantly working on it. You were saying I was an artist, and in that sense I don’t do things that people want me to do if they go against my idea of a well-designed garden.

I assume you also refuse a lot of commissions?

Many. People think I have an office with 20 or 40 people, but as I already said, I’m still working on my own, helped only by Anja. That’s why I’m very serious about developers, because the moment you say yes, you are handed over to a bookkeeper, an accountant, and a project manager, people who don’t understand your work, who only care about deadlines. It feels very bureaucratic, so I try to build a personal relationship with a client.

Describe your ideal client?

An ideal client has a clear vision of what they want but chooses me because of my approach. They know my work, they love it, and they won’t suddenly say, “But I want roses there!” The ideal client asks, “What can we do here?” and we engage in a dialogue about the surroundings, the house, the context, and the possibilities. Is it by the sea? In the mountains? Do we create a more wild garden with robust plants, or could we opt for something finer. From there, we can develop planting concepts that reflect that vision. It’s all about understanding and communication.

Piet Oudolf’s 4,000-square-meter garden at the Vitra Campus in Weil am Rhein, Germany, features about 30,000 plants and was completed in 2020. The gardens are situated between factory buildings by Álvaro Siza and SANAA. Photo by Julien Lanoo.

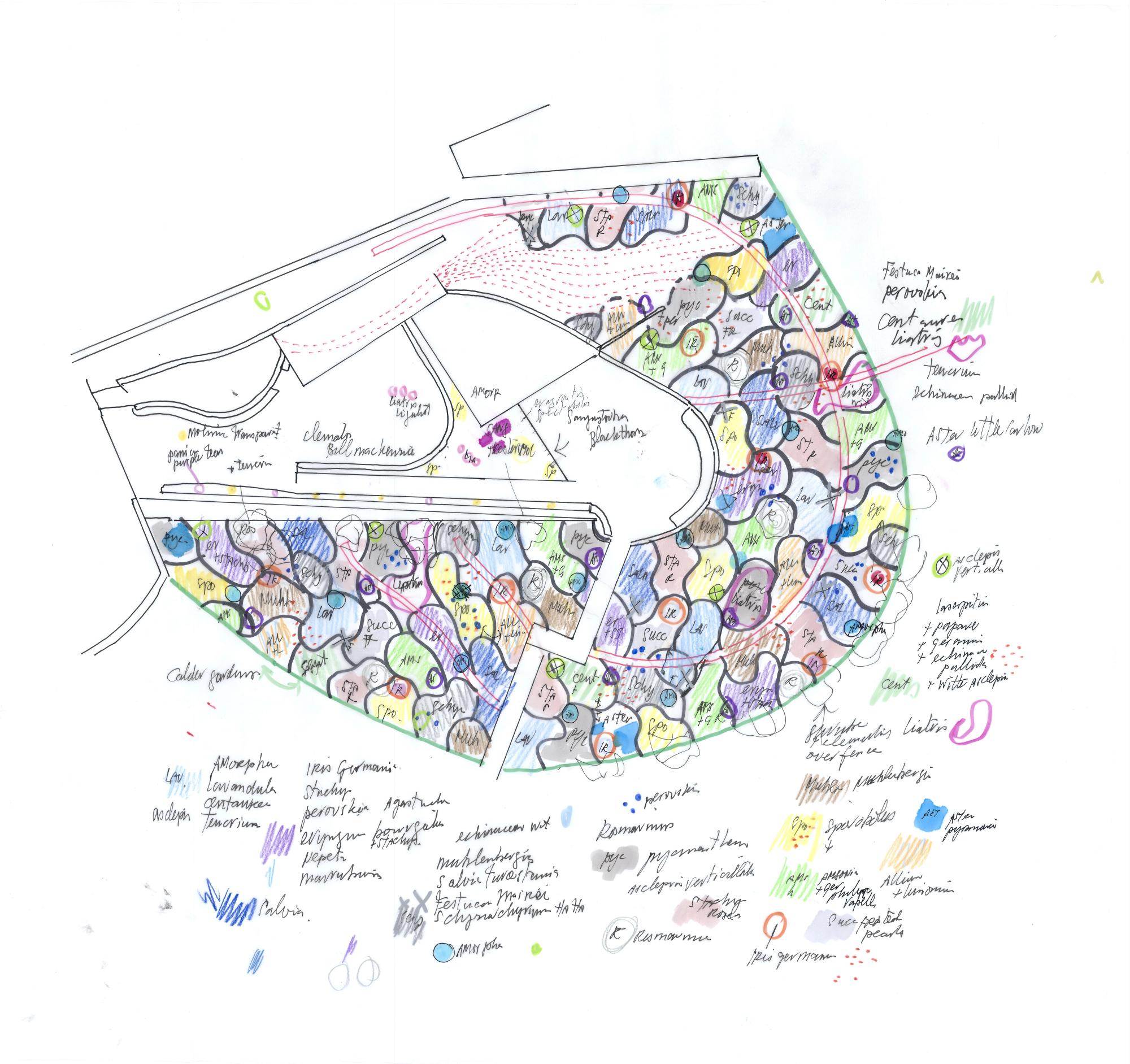

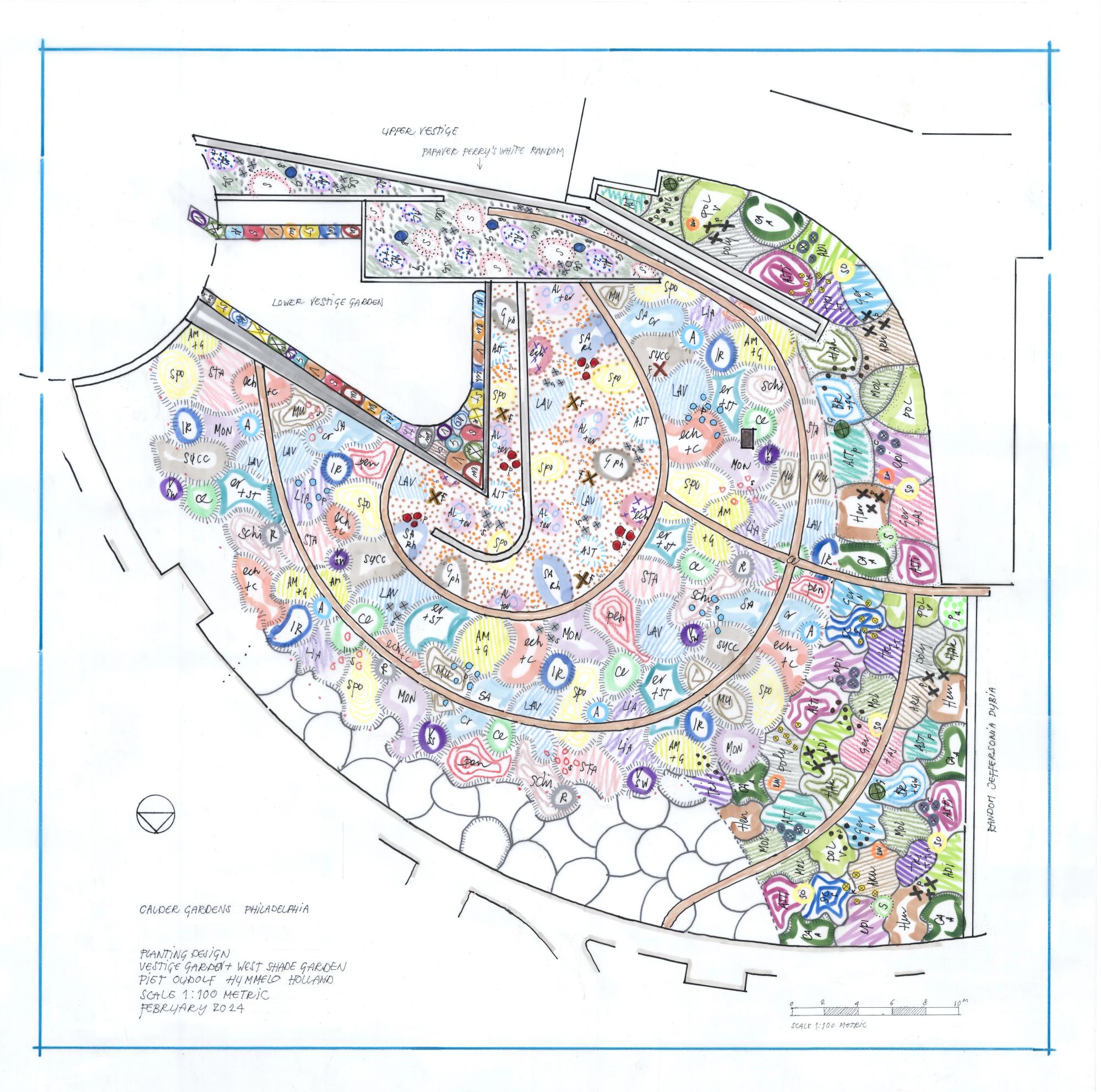

Oudolf's landscape plan for the Calder Gardens in Philadelphia. Courtesy of Piet Oudolf.

Oudolf's landscape plan for the Calder Gardens in Philadelphia. Courtesy of Piet Oudolf.

You just said “wild,” which is a word that people love using when describing your gardens. But when I look at your technical drawings, you create a Cartesian grid which you fill out with plants. There doesn’t seem to be anything wild about it.

No, there isn’t. We use large plant palettes. Some plants are native to wild, uncultivated areas, so you could say certain parts of the garden can look wild.But we use them in a very intentional, non-wild way. I think people describe them like that because my gardens are more loose and dynamic, and you see them change over time, throughout the months.

That’s really fascinating to me — how you grid out the plan and circle the plants in color. But the colors don’t represent the flowers, or the bloom, they represent the type of plant, right?

Yes, exactly. I used to work in black and white, but once I introduced color into my drawings, I realized it made it easier to see the sequence of specific plants. Color is about distribution and repetition. It’s more useful for creating balance in the plan. The color of the plants themselves is an extra layer, because I think primarily in terms of form and shape. Everything I design is based on texture, form, and shape, with color coming on top of that. You can see that it’s all about different shapes, and that’s what makes it so interesting. This is how we begin sketching. I didn’t start using color in my drawings until after working on the High Line.

In 2004, when you first started working on the High Line competition, did you know it would be such a transformative project?

Nobody knew. No one had any idea what the High Line would become. I heard that the original estimation for expected visitors was low — now it’s seven or eight million a year! At the time, I was working on the gardens at Battery Park. In the midst of that, they called me to participate in the competition for the High Line. I thought, “Okay, I’m already working in New York, why not take a look?” It was over a mile, all stretched out. I went online and saw videos of people supporting the project, and it looked fascinating. It was more of an intuitive decision for me. I thought, “If I can do 100 yards, I can do 1,000.” There were 700 competition entries, with big ideas — rollercoasters, swimming pools, and so on. But the board, the local community, and the people who wanted to rescue the High Line were all plant people. We were the only ones who came with ideas of planting, and that’s probably one of the reasons we won.

How has the High Line influenced the way you work?

I had to think differently. Normally, I work with groups of plantings and I compartmentalize — that’s the more traditional approach to my design process. But suddenly, I had to design for a mile and a half. I had to think more conceptually. The entrance is woodland, with tree strips and underplanting, which then opens into a meadow area. We gave names to specific areas, and these names dictated the design. I could only approach it step by step. It was completely new for me. I had to reinvent myself.

Portrait by Michael Cukr for PIN–UP.

Portrait by Michael Cukr for PIN–UP.

Portrait by Michael Cukr for PIN–UP.

Since then you’ve done many projects that also include large art installations, such as a meadow in Somerset, England for Hauser & Wirth, and the garden for the Calder Foundation here in Philadelphia. How do you create this conversation between landscape and art?

I don’t think too much about it. I think a good garden will always contribute to the art, and the art to the garden. You can make a garden where the art is more present and you can create a garden where the art is simply a part of your garden. Sometimes there’s a piece of art in my garden and I think, “What the hell is that doing there?” [Laughs.] But in general, I’m much more critical of myself. If theclient has art, I’m not going to say, “I don’t like this piece,” or “This piece is my favorite.” I just accept what they like because that’s theirexpertise. It’s like good chefs, who have tasted so much. I can say I don’t like it, but I can’t say it’s bad.

It’s funny, because I was going to ask you whether gardening is like cooking.

It’s different. You know, cooking is fixed on a product. And I think that what I do is not a product, it’s a process. You have to keep going over time. Some gardens are 20 years old and still look good, but they’re totally different from what we made. My gardens are not wild at all. They’re composed, like music — it can sound wild, but every note is there, in place.

You said earlier that the color of plants comes last in your approach to using them. But when you have a big red Calder sculpture, like here in Philadelphia, do you think about it in terms of the color palette at all?

No, I don’t. I just do what I think must be true. If I think too much about what other people want me to do, then I would never do it. Of course, when I have the right client, I can do what I like. I explain my ideas, I do it, and they’re happy. I’ve hardly had any unhappy clients.

Do you have a sense of accomplishment that you’ve introduced a new way of thinking to gardening?

I know that for sure, but I’ve worked for such a long time that it feels different to me than it does to other people. For me, it’s 50 years of work. You slowly grow into it — that feels different than when someone who meets you thinks, “Oh, he did that thing.” I’m also not someone who tells everybody I’m the best. [Laughs.] I always felt that I could do something special, but I didn’t know what that was until I met plants.

Aerial view of the Calder Gardens. Artwork: Alexander Calder © 2025 Calder Foundation, New York / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.