HOLY TERROR: ANDY WARHOL CLOSE UP BY BOB COLACELLO

by Michael BullockAndy Warhol entered my life when, at the age of twelve, I discovered one of his coffee-table books at the local Barnes & Noble in suburban Providence. Warhol’s nude male “landscape” series and the piss paintings were the first homoerotic art I had ever seen. Why was Warhol respected for making gay imagery when it was banned everywhere else? A few years later, freshly out of college, and freshly out, but with no real-life gay role models to draw upon I turned again to Warhol — or rather to Bob Colacello’s 1990 memoir, Holy Terror: Andy Warhol Close Up. It introduced me to a world I never knew existed: the day-to-day life of a wildly successful gay man who created the physical, social, and psychological spaces that provided refuge and empowerment to all types of outsiders, places where audacity, originality and decadence reigned supreme. I immediately moved to New York City seeking out the contemporary equivalent.

Holy Terror’s 514 gossip-fueled pages resonated with me so strongly because it was the first time I had ever learned about a homosexual who had both cultural and economic power and respect. I was also struck by Warhol’s collective approach to creativity. Once he established his own unique entry point into fame, he was emotionally and economically dedicated to building platforms that amplified his world view, and extending the invitation to other queer people, eccentrics, and societal outcasts. Their eventual fame, of course, was key in expanding his own, but the result was a broad newfound respect for talent that fell outside the narrow mainstream standards of the day. At the center of the center, Warhol created a world where queerness was not discouraged or merely tolerated but harnessed as a libidinous outsider frequency that moved both art and commerce forward. Learning about this in Colacello’s memoir, was the first time I ever realized there was a place in America where I might not have to censor myself in order to thrive.

Thinking about Warhol’s legacy through the lens of architecture, his Factory

could be considered one of most successful queer spaces in history, a clubhouse and workshop that projected images of queer and trans identities and same-sex desire and intimacy all over the Western world. But Warhol’s instinct was never born of politics alone.

Colacello writes: “Gay was not a word we used at the Factory, at least not to refer to homosexuality. Andy preferred ‘has a problem’... [...] Our nonchalance was infuriating to the rising generation of liberated homosexuals who had seen Andy Warhol as a vanguard figure. But Andy didn’t care about the correct political line; he cared about the correct style. [...] In the 60s, to be openly gay seemed daring and different; in the 70s the masses rushed out of the closet in droves. For the Factory, the raised fist of the new liberation movement was as uncool as the limp wrist of the Fire Island set.”

It’s fascinating to re-read these words in a post-AIDS-crisis, post-gay-marriage, post-Drag Race, post-Grindr world where LGBTQ+ people have more mainstream presence than ever before. Colacello’s statement provides a view into his and Warhol’s superficiality but the results of their shared philosophy also allowed their work to have a broader, more impactful, integrative force. Warhol favored world-building over acceptance-activism. He never asked for permission from straight society, creating on his own terms a thriving cultural ecosystem so big that it could not be ignored.

In New York City in 2022 Warhol’s legacy of queer audacity continues to manifest in new forms. In a recent Vogue review of fashion designer Telfar Clemens’s Fall Winter 2022 ready-to-wear presentation, fashion journalist Chioma Nnadi wrote: “Somewhere between a fashion show, public-access TV, and performance art, last night’s event was a full-on 90-minute immersion into the freewheeling creative world of Telfar; call it Clemens’s answer to Warhol’s infamous Factory.” And in this issue of PIN–UP, Rachel Hahn examines Hood By Air founder Shayne Oliver’s multifaceted, world-building strategy with respect to fashion, music, and creative output through his new venture Anonymous Club. At first glance, similarities between Clemens’s, Oliver’s, and Warhol’s enterprises focus on how they have all fostered and amplified their circles’ talents while creating their own cultural worlds that combine art and commerce in a self-sustaining, self-enriching loop. However, beyond these structural similarities lies a deeper philosophical connection. Like Warhol’s, the work of Clemens and Oliver never leads with gay identity while still being unapologetic in its queerness. Staying clear of rainbow flags and pride parades allows them to present more nuanced and subversive aspects of queer creativity to wider audiences. In the words of Colacello in Holy Terror: “Andy’s gayness would become, like his very obvious wig, so out in the open that it was taken for granted.”

Andy Warhol signing autographs in Los Angeles, 1972. Courtesy of Los Angeles Times

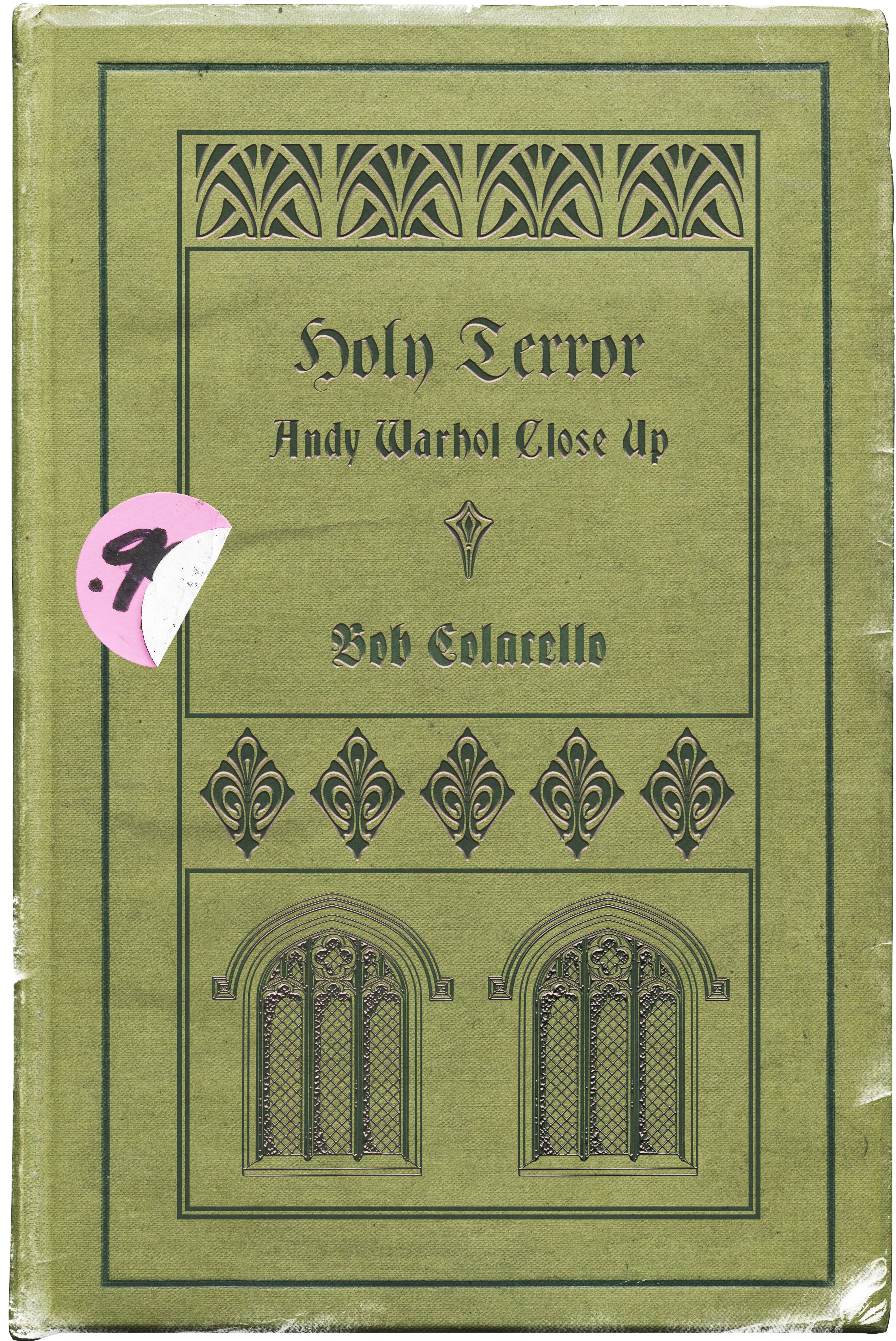

"Fake" book cover artwork by Matthew Raviotta for PIN–UP