Rock Paper Rock by Anna Neimark and Andrew Atwood of First Office. Architectural reinterpretation of Stonehenge. Photography by Marco Zorzanello.

Sylvia Lavin's Venice Biennale project in James Stirling’s Book Pavilion. Photography by Marco Zorzanello.

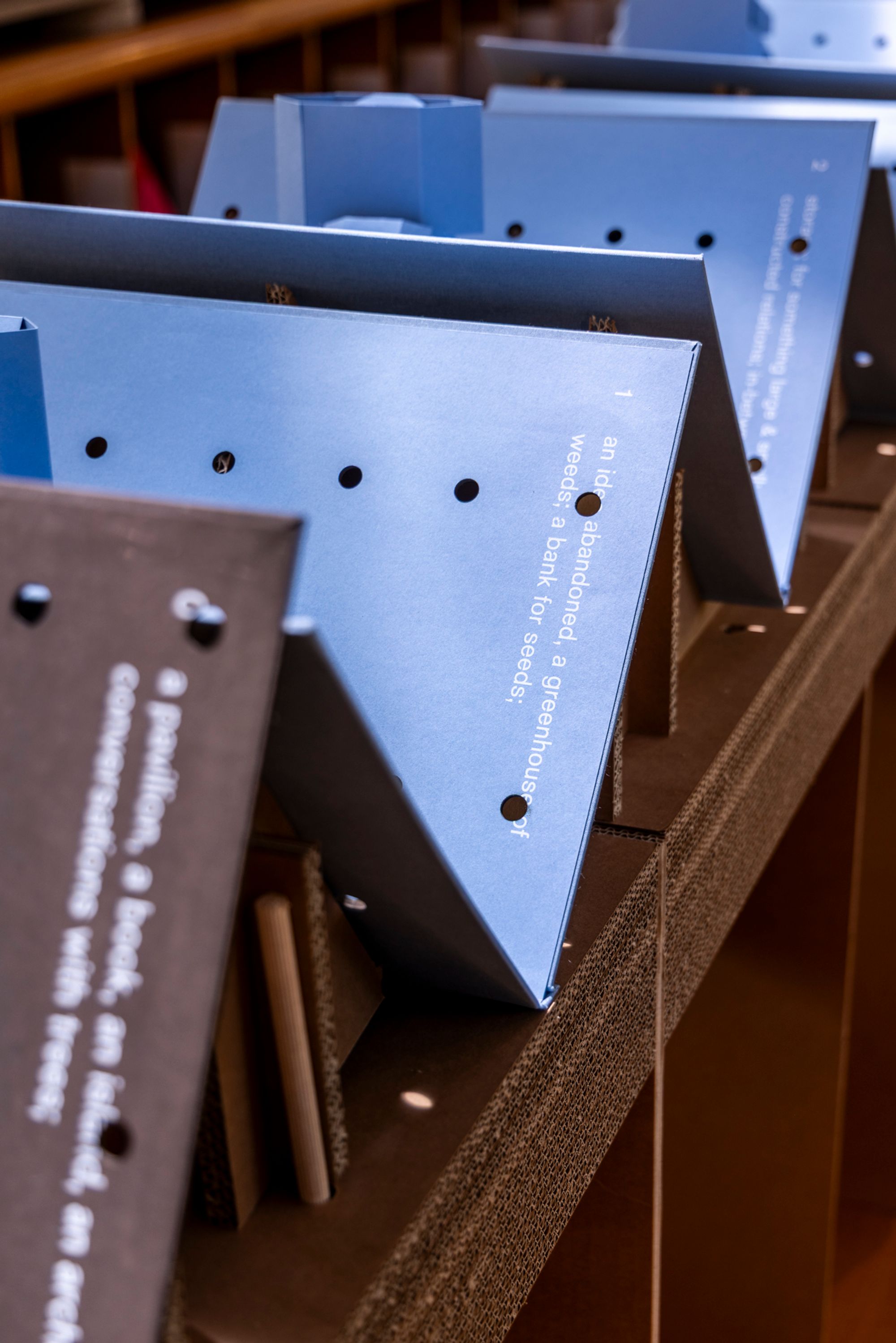

In a Biennale largely preoccupied with forward-looking solutions, Sylvia Lavin’s project makes a compelling case for looking back. Though she describes herself as someone who was never particularly sentimental, Lavin has created one of the most evocative interventions at the Venice Architecture Biennale this year. Installed within James Stirling’s iconic Electa Book Pavilion (Stirling, Wilford & Associates with Thomas Muirhead, 1989–91), her project is a meditation on architecture’s long and often uneasy entanglements with matter — earth, water, air, fire — and with books. An architect and historian who now admits to feeling déçue with her discipline, Lavin has crafted something featherlight and weighty all at once: delicate models made from Carta Azzurra — an azure paper once favored by Renaissance artists — are exposed to sun, humidity, and wind, while facsimile books trace architecture’s environmental and colonial legacies. Beneath the Venetian sun — perhaps the fiercest element of all — Carlo Antonelli sits with Lavin, two Diet Cokes between them, to unpack how her elemental imagination and intellectual precision have produced a project that quietly, and confidently, steals the show.

Sylvia Lavin’s The Perimeter of Architecture: Amid the Elements at the Bookshop Pavilion.

James Stirling and Thomas Muirhead’s Venice Bookshop Pavilion, 1991. Courtesy of Archiweb.

Have you always admired the James Stirling building, or did it just seem like an ordinary bookshop?

The wonderful thing about the Stirling Pavilion is that even though it comes from this moment in which the architect genius was such a cult figure — and Stirling is an enormous cult figure — so many of the architects who have been to the Biennale time after time will have no idea it’s a Stirling building. It’s amazing he was able to fly under the radar like this — the idea of the invisible Stirling is wonderful.

In a way, it’s an example of architectural reuse.

It is reuse. And they’re building a new book pavilion, as I understand it, for two reasons: you can no longer have a bookshop without a café, and you can’t put a café in the Stirling Pavilion. It points to how bookshops are no longer about books — they’re about social gatherings. Even if people did not know the pavilion was a Stirling creation, it was very often a meeting point. “Let’s meet at the bookshop.” So even though it was intended to be super-focused on books, it was also a social magnet, almost in spite of itself. I don’t think that was the point of the design, but it became that.

The great thing about buildings is that they can do whatever they want, in a way.

They have a way of collecting people and practices. That’s all. The other thing that I find very amusing about the Stirling Pavilion is that its interior environment is not very good for books. So it’s both accommodating and hostile in elemental terms. Carlo Ratti, who curated this year’s Biennale, focused this year’s programming on the “perimeter of architecture.” In my understanding, for the Stirling Pavilion, he had in mind a kind of three-dimensional bibliography in which there would be some display of books about morphology and psychoanalysis, which was a trend among architects in the 90s.

Soil Assemblages by Erin Besler of Besler & Sons. Blue model of a building under construction. Photography by Marco Zorzanello.

So let’s give some limits. Let’s put up a perimeter in cartographic terms.

I think for him it was about what is just outside the fence. I don’t think it was about containing. It was about what is on the edge of architecture. How far has architecture gone? And then, I found two drawings in the book pavilion’s archive that I found really deeply fascinating. One was a structure for displaying books that was never built. The top surface of the bookcase was designed so that you look at books through the window and from the inside — there were two books on each side, and you could see different ones depending on which way you looked at them. So the perimeter was porous. I thought, okay, if we’re in a building that imagines its own perimeter to be open, we have to do something that straddles the interior and the exterior. It’s almost like a membrane. I suppose it’s part of a Modernist fantasy because there’s no glass — it’s actually just open. Stirling made many sketches of the building. Some show the building as a Corbusier ocean liner, and others showed it as what they called in the 80s a primitive hut: a big roof with four columns.

First of all, why this focus on porosity? It comes up a lot in this year’s Biennale, and Ratti talks about it very frequently.

I assume it’s because porosity can be a critique of architectural hermeticism. I think fixed perimeters are the common denominator of architecture’s outsized carbon footprint. So whether it’s borders, temperature, wind, or light, anti-porosity, or perimeters that allow nothing to cross them, has been one of architecture’s biggest contributions to climate change.

Plants as Collaborators by Besler & Sons/Erin Besler. Cerulian model of an amphitheater decorated with vibrant vegetation. Photography by Marco Zorzanello.

But the real question is: why have you always been interested in elements?

Well, for me, elemental philosophy is a way of looking at the world. It makes earthly matter philosophical. I’m anxious about the data-driven positivism of most climate environmental discourses. It leads to more technocratic solutions, which are always a problem. I’m not against practical solutions, but I think they can’t be drivers alone. They have to also be philosophical and intellectual. So elements, or what is called elemental philosophy, I think is an umbrella that enables all of those things to remain together.

What kind of elements of this philosophy did you put in the pavilion?

I tried to group them in ways that were particularly salient to architecture. Earth, when it takes the form of stone, is more obviously architectural than some other things. Air, when it comes into contact with humidity, is a huge dimension of environmental control systems. So I curated the elements to make salient points of contact with architecture. Fire is an interesting one, for example. Fire has such a fascinating and long history.

Especially now.

Yes, but the Arsenale is famous for having had fire after fire, not because of the climate crisis, but because gunpowder depots would explode. Or sugar, which is highly flammable, and came to Venice even before it was developed by colonists in the Caribbean. It was stored in basements and would catch fire. So there’s a pyrological history to the Arsenale that is absolutely fascinating. And the model in my exhibit is particularly interested in fire as a weapon against books in particular.

Everything Is in the Process of Becoming Something Else by Michael Meredith and Hilary Sample of MOS. Centerpiece made of carta azzurra, a popular Venetian paper during the Renaissance. Photography by Marco Zorzanello.

Rock Paper Rock by Anna Neimark and Andrew Atwood of First Office. Architectural reinterpretation of Stonehenge. Photography by Marco Zorzanello.

A World Previous to Ours by DESIGN WORLD. Organic sculpture of carved and layered cardboard. Photography by Marco Zorzanello.

In general, though, the basic element of the exhibition is books.

I wanted to make sure that a book pavilion would not be misunderstood as an information pavilion. In fact, when the building was finished in 1990, it was the height of textuality in architecture. And in the famous Strada Novissima [the 1980 Venice Architecture Biennale installation featuring works by Frank Gehry, Hans Hollein, Rem Koolhaas, and more], architecture is a screen, [built by the Ente Gestione Cinema in the workshops of the famous Roman film studio] Cinecittà — flat like a film set. This flatness was a metaphor for the page of a book, in which a façade was not something structural — it was a text to be read. This was the conceit of that period: architecture as text. Book culture is expansive. Books are also made out of paper. They’re industries. There are machines for reading. Books draw people around them, and so forth.

And you incorporated carta azzurra, the handmade blue paper that became a favored material for artists and printers in early 16th-century Venice.

The minute you say book, paper, and Venice, you get to carta azzurra. And, of course, carta azzurra is also fascinating because it is elemental in all of these senses. Ratti is very interested in circularity. When I started looking into the history of paper production in Venice, I realized it stretched as far as Genoa. I had no idea. It was such a huge thing. Paper production extends all that way, and it requires people moving around rags that are dyed with indigo or smalt to mills in the Valle delle Carteria [a historic alley in Bologna once associated with papermaking and bookbinding]. When paper became white, it was this moment when paper production started its journey towards becoming one of the most toxic industrial processes ever. Artists were encouraged to think of the blue as atmospheric, but they eventually figured out how to make naturalistic images without needing blue anymore. So blue paper, for me, was elemental — to go from a rag to the invention of atmospheric perspective, to me, is a fabulously suggestive dynamic of how earthly matter and ideas work on each other to produce what becomes a convention.

Rock Paper Rock by Anna Neimark and Andrew Atwood of First Office. Installation hangs from the ceiling of the Book Pavilion. Photography by Marco Zorzanello.

Nyame Dua (Akan Twi, “Tree of God”) by DK Osseo-Asare of Low Design Office. Photography by Marco Zorzanello.

Terra non Firma I by Rachaporn Choochuey of all(zone). Photography by Marco Zorzanello.

And then you used the blue in this floating, paper architecture in the middle of the exhibition.

I was interested in certain books about underexplored architectural and elemental possibilities. Stonehenge, for example. From a certain point of view, it is a peripheral monument in multiple senses. It was literally on the edge of the Roman Empire — about as far north as you could go and still remain within its borders. It’s on the edge of history because it’s prehistorical — it’s on the edge of written language. When British travelers started to look at it again in the early 16th century, their only way to conceptualize such big pieces of stone was to imagine them as a Roman temple. There are these crazy drawings of architect Inigo Jones and other people trying to understand how Stonehenge could be assembled as a Roman temple. In that case, I gave architects who I knew were interested in prehistoric stone books on Stonehenge and commissioned them to make me something that shows how the encounter of architecture with Stonehenge was a different story than the one that we’re familiar with.

Were you fascinated by pop-up books when you were a kid?

I was not a very sentimental kid, but I love book technology, like Victorian theatre boxes, all of those things. Those books do sort of stand in for books as technological artifacts.

You also made a tribute to James Stirling with the models.

I wouldn’t call it a tribute.

Well, there’s the Stirling Pavilion in one of the models — the one in the center.

Stirling was asked not to cut down any trees when designing the pavilion so, in protest, he made a series of sketches proving to Francesco Dal Co that if you left all the trees you would end up with a bad building. Stirling won and the trees were removed but I wanted to suggest that designing around the trees might have produced even better architecture. The pop-up models by MOS, although they begin with Stirling’s sketches, embrace and even amplify the complexity that he wanted to avoid.

Everything Is In the Process of Becoming Something Else by Michael Meredith and Hilary Sample of MOS. Close-up of the carta azzurra centerpiece. Photography by Marco Zorzanello.

Nyame Dua (Akan Twi, “Tree of God”) by DK Osseo-Asare of Low Design Office. Typical view of the installation: architectural model presented along side books. Photography by Marco Zorzanello

How many books do you have in your house?

A lot, but I don’t like them.

What do you mean?

I don’t like to collect books.

Me neither.

First of all, that’s for libraries. Go to the library. People are so fucking lazy that they can’t go to the library. Also, there’s a kind of orgoglio [a strong sense of pride] — “I have this many books, or you have a first edition of this or that.” I’m not into it.

But in any case, you’re a book lover.

I do love books. I do love books.