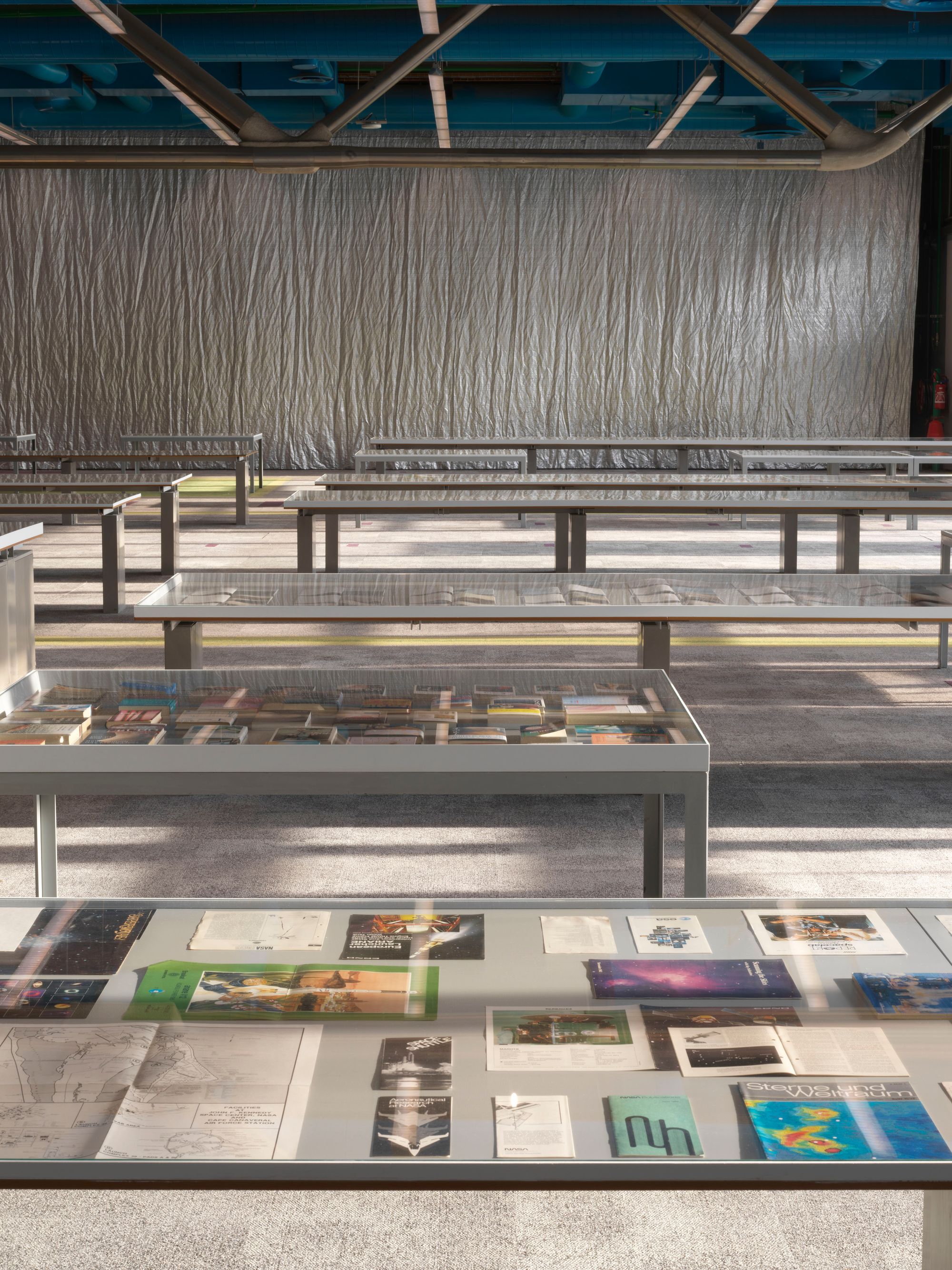

Display tables of works on paper, including PIN–UP. Photography by Jens Ziehe courtesy of Centre Pompidou.

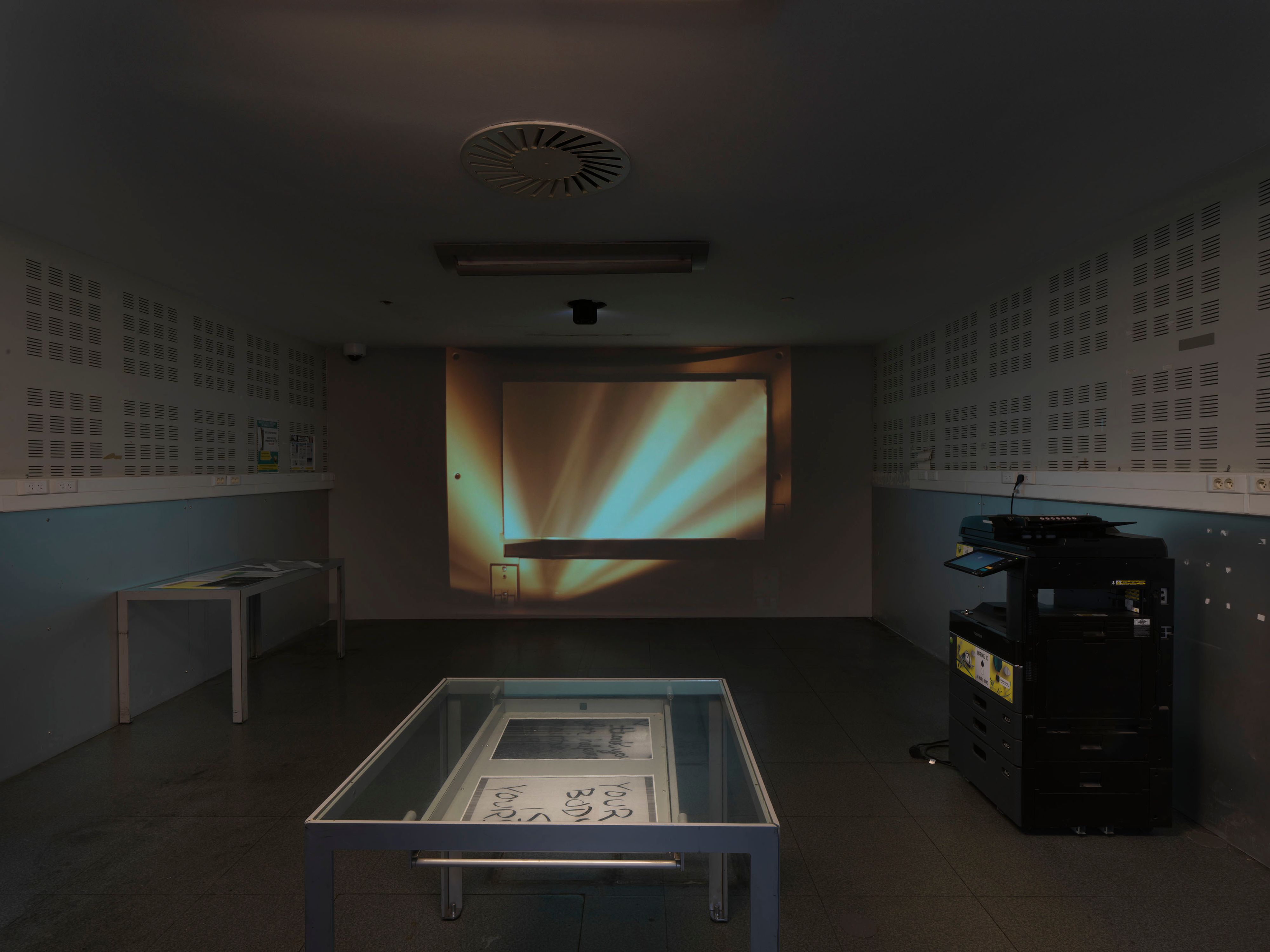

Exhibition view of Wolfgang Tillmans’s Nothing could have prepared us – Everything could have prepared us at the BIP. Photography by Jens Ziehe courtesy of Centre Pompidou.

In January 2027, Paris’s Centre Pompidou, that fun palace of art, cinema, music, and public emancipation, will turn 50. It’s a major milestone for a building that, with hindsight, has come to symbolize both the apogee and the end of postwar dreams of utopia. But no one will be celebrating the anniversary, because the Piano and Rogers-designed monument will be closed for a major refurbishment — this fall, Beaubourg, as it is known locally, will shut its doors for five long years, after which, it is hoped, the building will resume service in an improved form fit for the 21st century.

Instead of a birthday celebration, we have an elegy, put together by the artist Wolfgang Tillmans who was invited to fill the entire 6,000 square meters of the Bibliothèque publique d’information (BPI) — the giant public library on level two that is set to be transformed and enlarged by the architects Moreau Kusunoki and Frida Escobedo Studio. And what an elegy! Nothing could have prepared us, Everything could have prepared us, as Tillmans has titled his show, reads like a stocktaking of our times, a portrait of where we’re at and how we got there, a lament for all our dashed hopes and a catalogue of all those warnings we saw and yet failed to see. Like all great works of art, this massive installation, which bears witness to the extraordinary power of photography, operates on numerous levels — not only the political, the sociological, the autobiographical, the nostalgic, the hopeful, the tragic, the comic, and the aesthetic, but also, in a way unusual for this kind of exercise, the architectural.

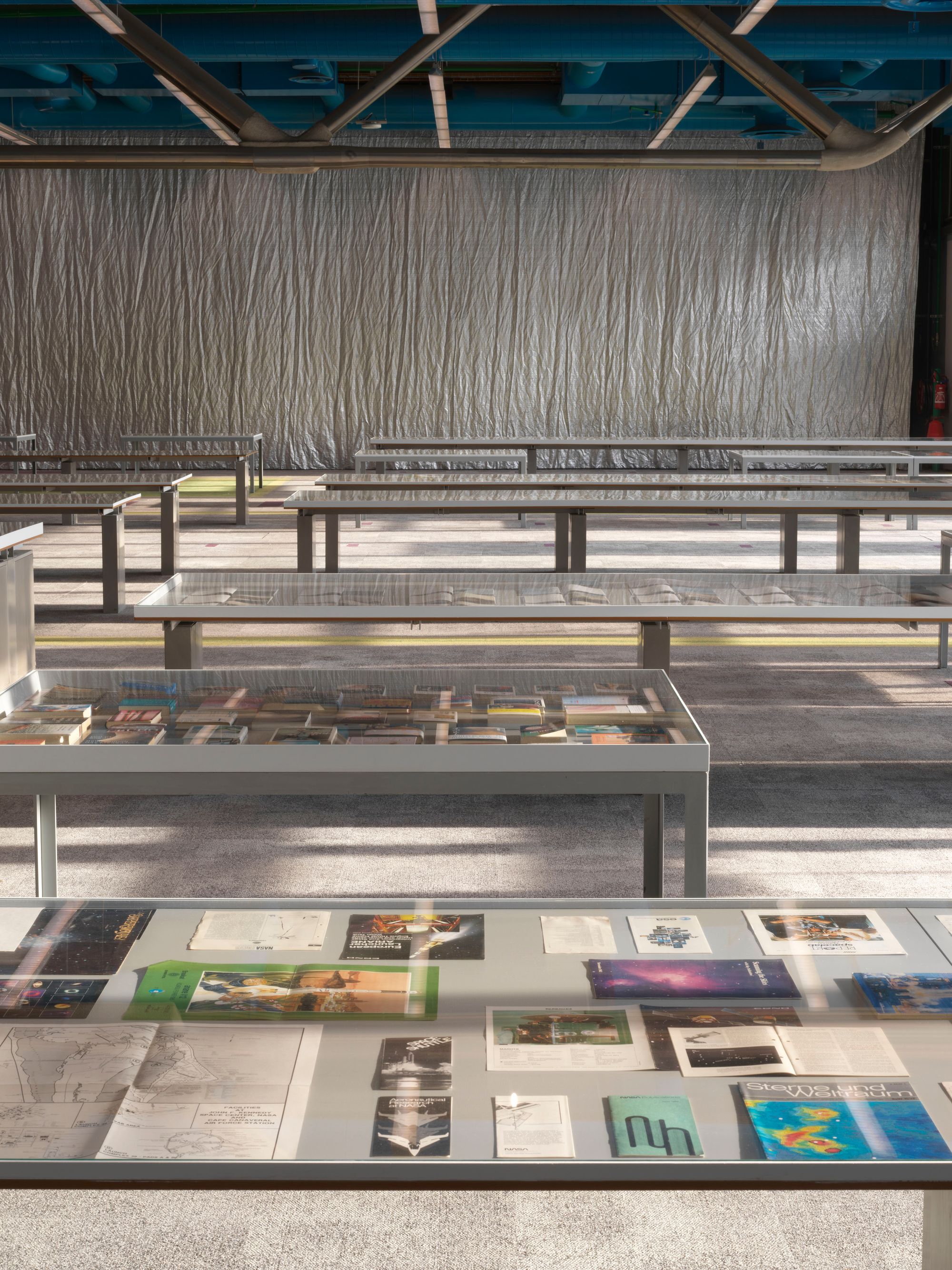

Exhibition view of Wolfgang Tillmans’s Nothing could have prepared us – Everything could have prepared us at the BIP. Photography by Jens Ziehe courtesy of Centre Pompidou.

Display tables of works on paper, including PIN–UP. Photography by Jens Ziehe courtesy of Centre Pompidou.

Assorted electronic and paper displays of Tillmans’s photography. Photography by Jens Ziehe courtesy of Centre Pompidou.

Though most of the millions of tourists who have ridden Beaubourg’s “caterpillar” escalators over the years had no clue it was there, the BPI was central to the Centre Pompidou’s public mission. Intended — in a pre-Internet era — as a place where anyone and everyone could access news, science, and all other kinds of knowledge, it was open until 10:00 pm and free to all, with no need for any kind of registration or membership card. With holdings that count in the millions, it could accommodate 2,200 readers at one sitting. For a bibliophile and paper junkie like Tillmans, whose worldwide fame is in large part due to his work for magazines, the BPI is the perfect setting for an immersive perambulation through his 40-year-long career. “It’s been an incredible honor to be invited to show at the Pompidou,” he said at the press conference, “not only because it’s the last exhibition before closure, but because the building has been an inspiration to me since my early teens. Coming here as an adolescent from a small town in North Rhein-Westphalia was like a realization of what is possible, what culture can do, how exciting it can be, and how technology and culture work together to make new forms.”

Portrait of Wolfgang Tillmans in the Bibliothèque publique d’information. Courtesy of Centre Pompidou.

Filling 6,000 square meters would be a daunting prospect for any artist, but, as Tillmans pointed out, the BPI is especially challenging for him given his penchant for hanging works on walls — the library is largely devoid of them. Among the delights of Nothing Could Have Prepared Us is how he grapples with the found object that is the BPI and turns adversity to his advantage. His approach is typified by his handling of the library’s old gray carpet, which is marked with green painted lines that show readers the way to the different departments. Taking it out would have delayed opening by two weeks, on what was already a very tight schedule, so Tillmans simply left it in place, as a souvenir of the library’s activity and also a sort of metaphor of a circuit board. And as shelves, partitions, and other furnishings were removed, traces of an older, purple carpet emerged — when the gray carpet tiles were laid, around the year 2000, the workers simply cut around anything that was too cumbersome to move, leaving the original in place. In this way, an archaeology of the library’s occupation emerged, one whose manner of creation has certain parallels with the photograms that form part of Tillmans’s oeuvre.

Nothing could have prepared us, Everything could have prepared us installed into fabricated gallery spaces in BPI. Photography by Jens Ziehe courtesy of Centre Pompidou.

Since walls are in short supply, Tillmans uses all those at his disposal, with photos displayed in out-of-the-way peripheral corridors, as well as on the glass façade, in library shelves, and on library tables. Horizontal glass display cases contain all sorts of books, magazines, and paper ephemera, while long mirror-polished tables underline the fact that the building itself is also an exhibit, bringing its famous colored ceiling ducts into the same plane of vision as the other works on show. Indeed, the juxtapositions are pregnant with playful associations: a male nude dialogues with a bright-red fire-hose reel; photos of rats in drains and trash line a corridor strewn with boxes of rodent poison; in an image taken at airport security, the signs marked “Emergency exit” and “Rest of World Passports” point in the same direction as the Pompidou’s own emergency-exit lights; while a tiny photo of two bare-chested boys in a club is taped beneath the label “510.0 math textbooks (secondary level).”

Fabricated gallery walls displaying Tillmans’s photography. Photography by Jens Ziehe courtesy of Centre Pompidou.

Series of Tillmans’s photographs on an architectural display. Photography by Jens Ziehe courtesy of Centre Pompidou.

Wolfgang Tillmans, its only love give it away (2005). Courtesy Galerie Buchholz, Galerie Chantal Crousel, Paris, Maureen Paley, London, David Zwirner, New York.

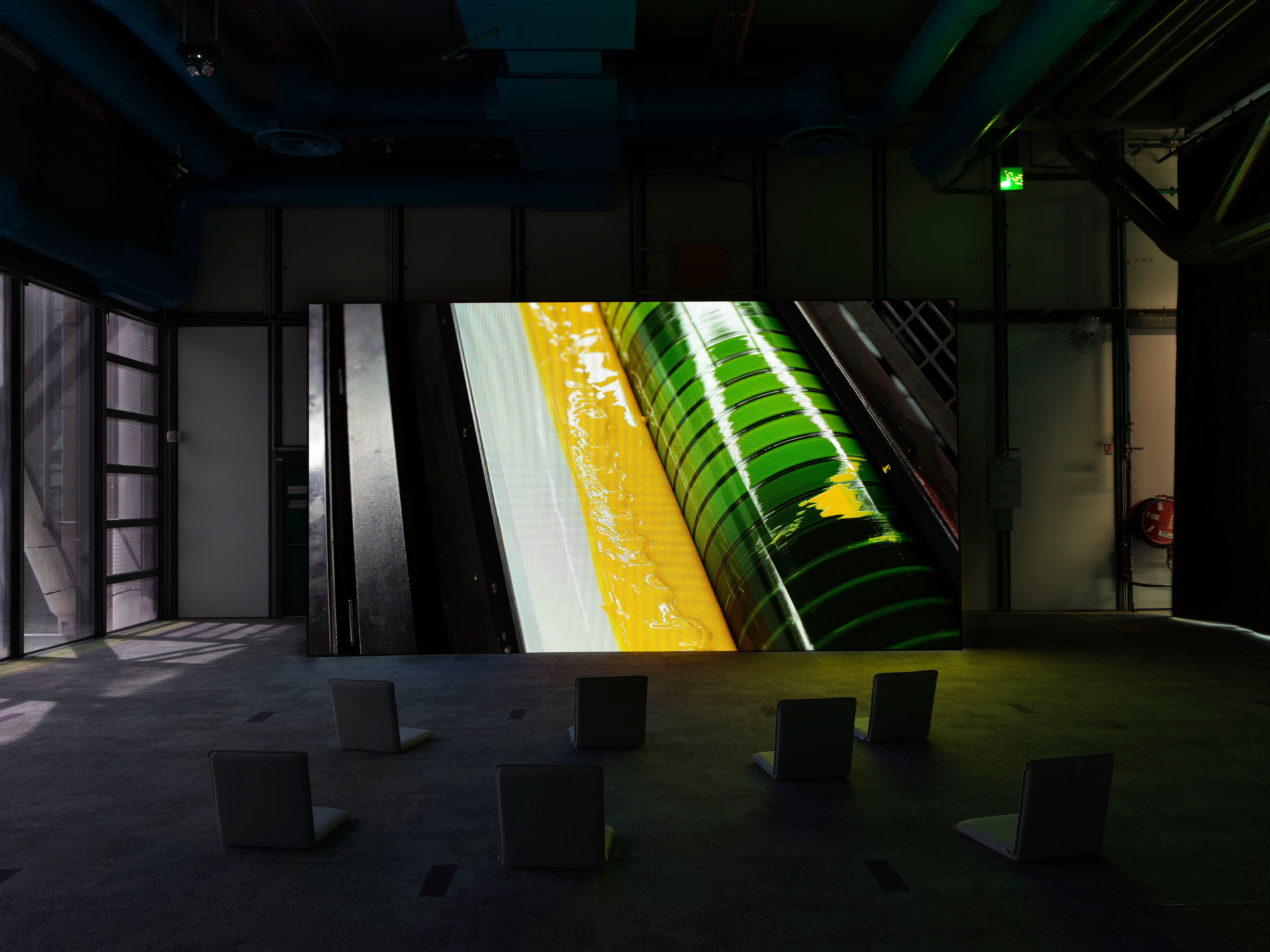

“Architecture has been an interest of mine for a long time, and not only because I realized through the 90s that what I do is actually spatial installations in architectural rooms,” Tillmans explained. “I began observing architecture ever more closely and intensely, and found it fascinating how real, lived architecture is so different from the architecture that is drawn in plans, or even from a building as handed over and photographed on the day of its completion, since almost immediately it takes on a life of its own.” It is precisely this “life of its own” that he celebrates at the BPI: among the works displayed we find BPI portraits (2024), a film he made of the library’s users, and Library shelves with an unusual amount of space around them (2023/2025), a “still life” compiled from 12,000 retired volumes. What’s more, Tillmans has kept the BPI’s photocopy room in operation, a nod to the origins of his own practice back in the 80s that allows visitors a little bit of agency in their interaction with the show.

Projected photographs by Tillmans. Photography by Jens Ziehe courtesy of Centre Pompidou.

Wolfgang Tillmans’s Nothing could have prepared us – Everything could have prepared us at the BIP. Photography by Jens Ziehe courtesy of Centre Pompidou.

Wolfgang Tillmans, Echo Beach (2017). Courtesy Galerie Buchholz, Galerie Chantal Crousel, Paris, Maureen Paley, London, David Zwirner, New York.

Tillmans’s longstanding interest in the lived life of buildings is also present in Book for Architects, a 450-image two-channel projection that he compiled at the request of Rem Koolhaas for the 2014 Venice Architecture Biennale, and which has now joined the Pompidou’s collections. Indeed architecture is everywhere, from portraits of architects — Koolhaas, Renzo Piano, Oscar Niemeyer — or of buildings — Library ladies (São Paulo) (2010), which shows women using the library at Lina Bo Bardi’s celebrated SESC Pompeia. Data Center Warm Air Outlets, Santa Clara (2023) is an ironic nod to the tubes at the Pompidou, and Macau Bridge (1993) contrasts the massive concrete piers of a bridge under construction with Beaubourg’s steel gerberettes. Ceiling Scan (2025), a laser installation intended to focus attention on the Pompidou’s own ceilings, also recalls the artist’s longstanding interest in club culture.

Exhibition view of Wolfgang Tillmans’s Nothing could have prepared us – Everything could have prepared us at the BIP. Photography by Jens Ziehe courtesy of Centre Pompidou.

Exercises in world-building, Tillmans’s exhibitions are meticulously prepared, as he shows us in the BPI display, where we see some of the giant analogue models he used to help devise the hang, a theme he has spoken about in the pages of PIN–UP (the issue in question features in the show's display tables). Organized like a library borrowed from Borges, with a classification system unknown to Dewey and his decimals, Nothing could have prepared us, Everything could have prepared us takes the visitor down myriad rabbit holes, its chance encounters and unexpected associations as rich as anything found on the Internet. Except here, in this labyrinthine walk-in picture book, you grapple with real matter, real objects, real people, and real space. As a paean to the Pompidou, and all it stands for, it’s an absolute triumph.

Exhibition view of Wolfgang Tillmans’s Nothing could have prepared us – Everything could have prepared us at the BIP. Photography by Jens Ziehe courtesy of Centre Pompidou.