SCOTT BURTON’S BODIES IN SPACE

A Sculptor’s Vision for Queer Spaces, Rediscovered and Under Threat

by Oscar Peña

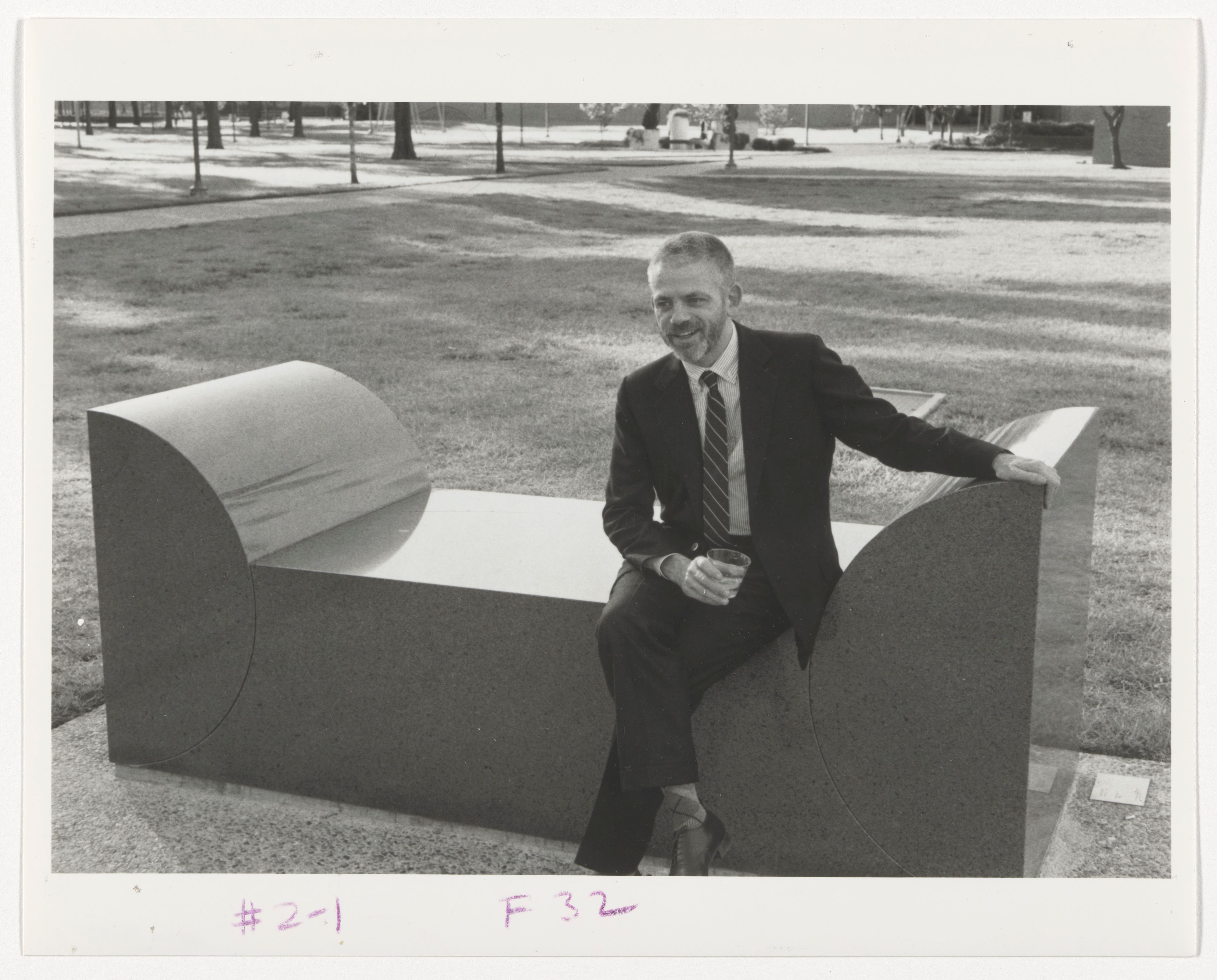

Scott Burton sitting on a granite bench at the University of Houston, College of Architecture Building, ca. 1986; gelatin silver print; 8x10 in. Scott Burton Papers, V.37. Photography by Jonathan E. Jareb.

When an opulent new train hall opened in New York in 2021, most of the commentary focused on one thing: there was nowhere to sit. Walk along its vast marble floors today, and you’ll still see winding rows of people crouched in undignified squats next to their suitcases. In the 1970s and 80s, the artist Scott Burton sought to disrupt this increasingly hostile urban environment by creating more humane public spaces, prioritizing places to sit and spend time in over ones to spend money in and pass through.

Burton was born in Alabama in 1939 and moved to New York in the 60s, quickly becoming enmeshed in the city’s experimental art and literary worlds. In 1969, he participated in a series of freewheeling art festivals called Street Works, contributing subtle, sometimes invisible performances and interventions, like plugging his ears with wax or cross-dressing in a modest outfit. Playing out across New York’s streets, these events collapsed the boundary between performer, audience, and passerby, demanding heightened attention to other’s actions and one’s own. Later moving indoors to small theatres, Burton’s performances grew more complex. He analyzed every gesture to generate a taxonomy of movement and meaning, from subtle shifts in posture to how close one body is to another. These investigations of body language and social presentation remained essential to Burton’s work for decades.

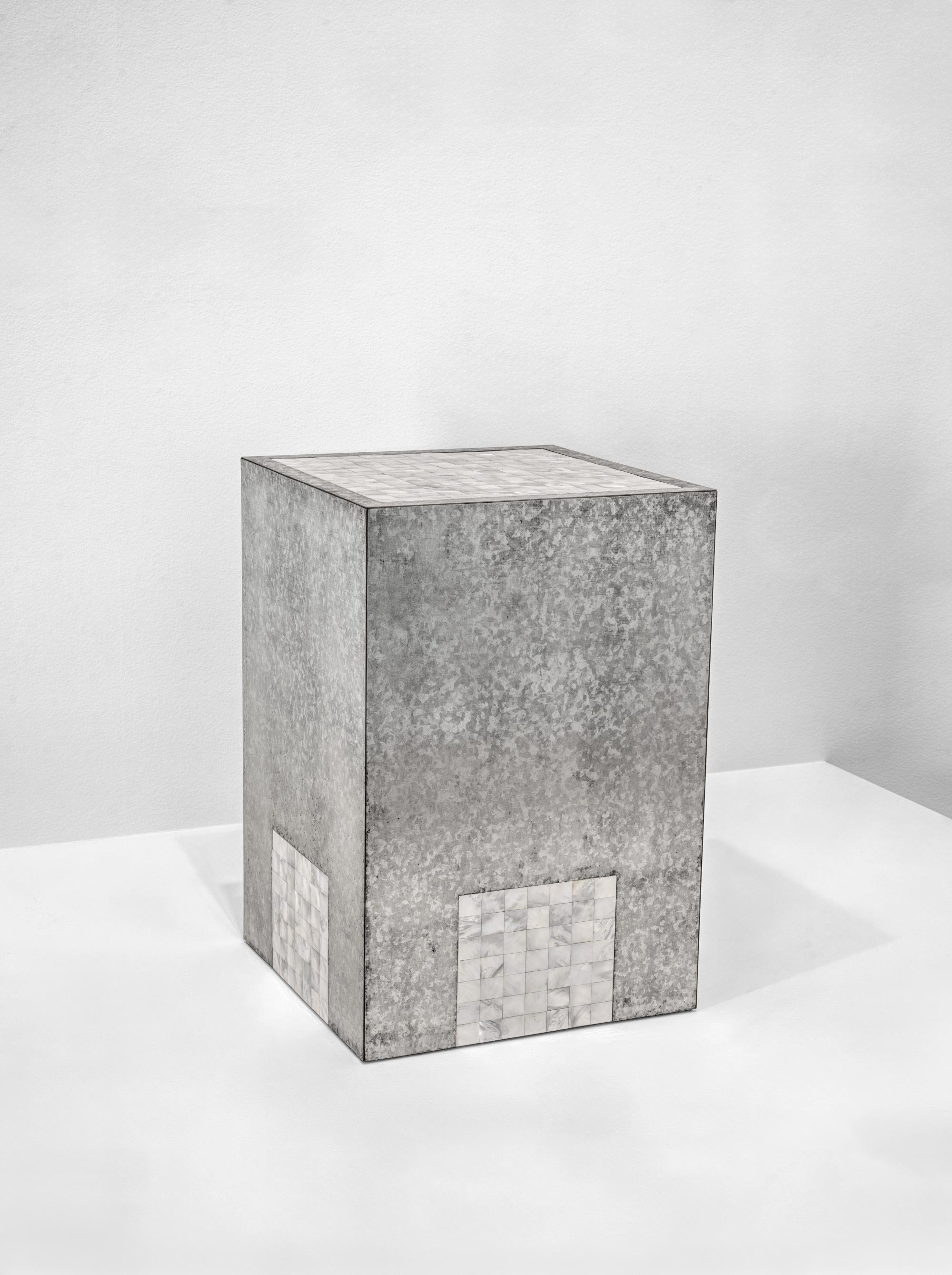

Photography by Alise O'Brien courtesy of the Pulitzer Foundation

Burton was most interested in the ways queer people, especially gay men, study and mimic others’ gestures as social camouflage while developing covert signaling choreographies only legible to those in the know. Bringing lessons from cruising, bathhouses, and bars into theaters and museums, Burton applied conceptual art’s interest in systems, repetition, and variation to how queer people really lived. Since his death from AIDS-related complications in 1989, Burton’s work has been relegated to the fringes of the art world — the kind of artist only other artists would reference. If Scott Burton: Shape Shift, a recent exhibition at the Pulitzer Arts Foundation in St. Louis, is any indication, this is about to change.

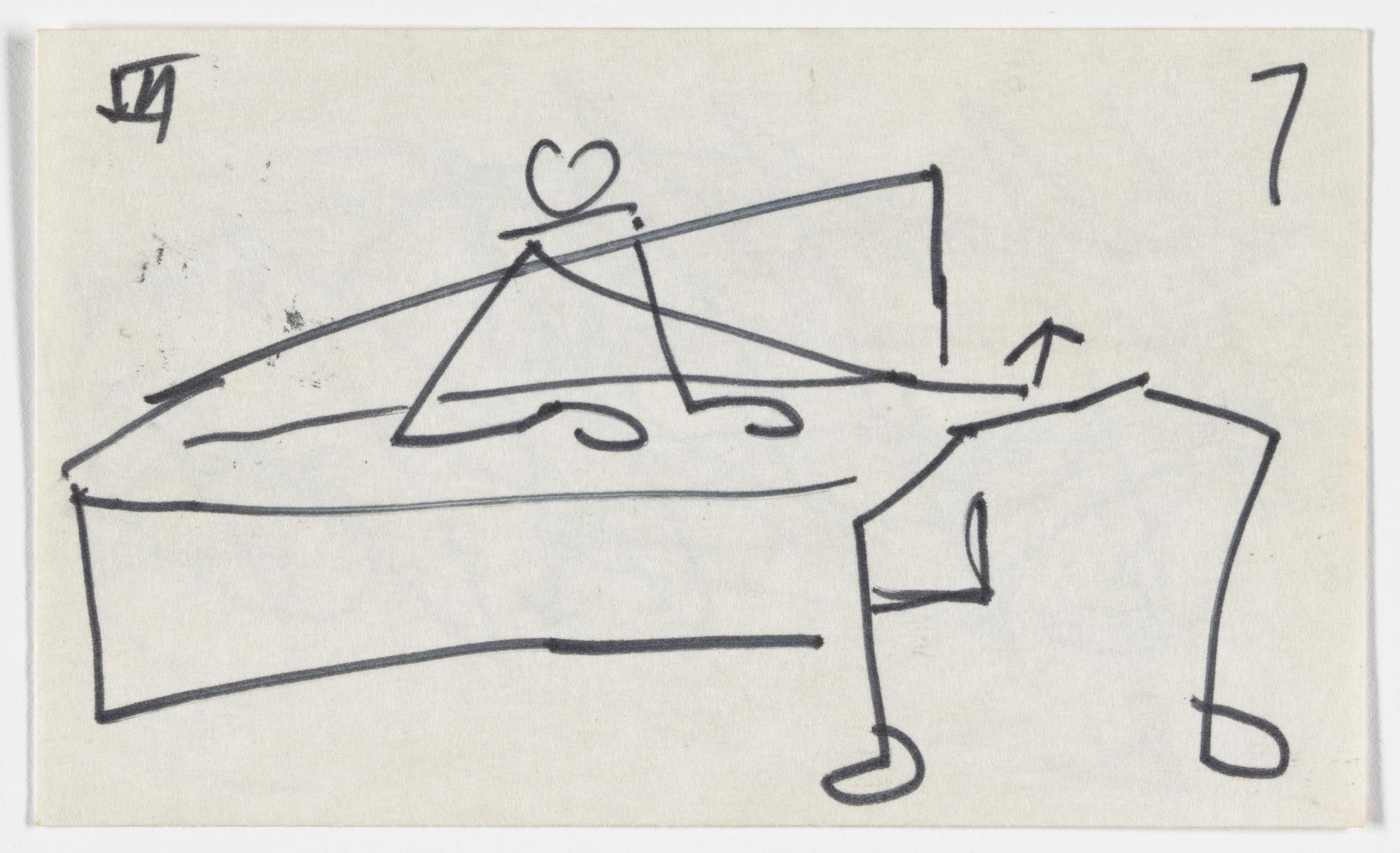

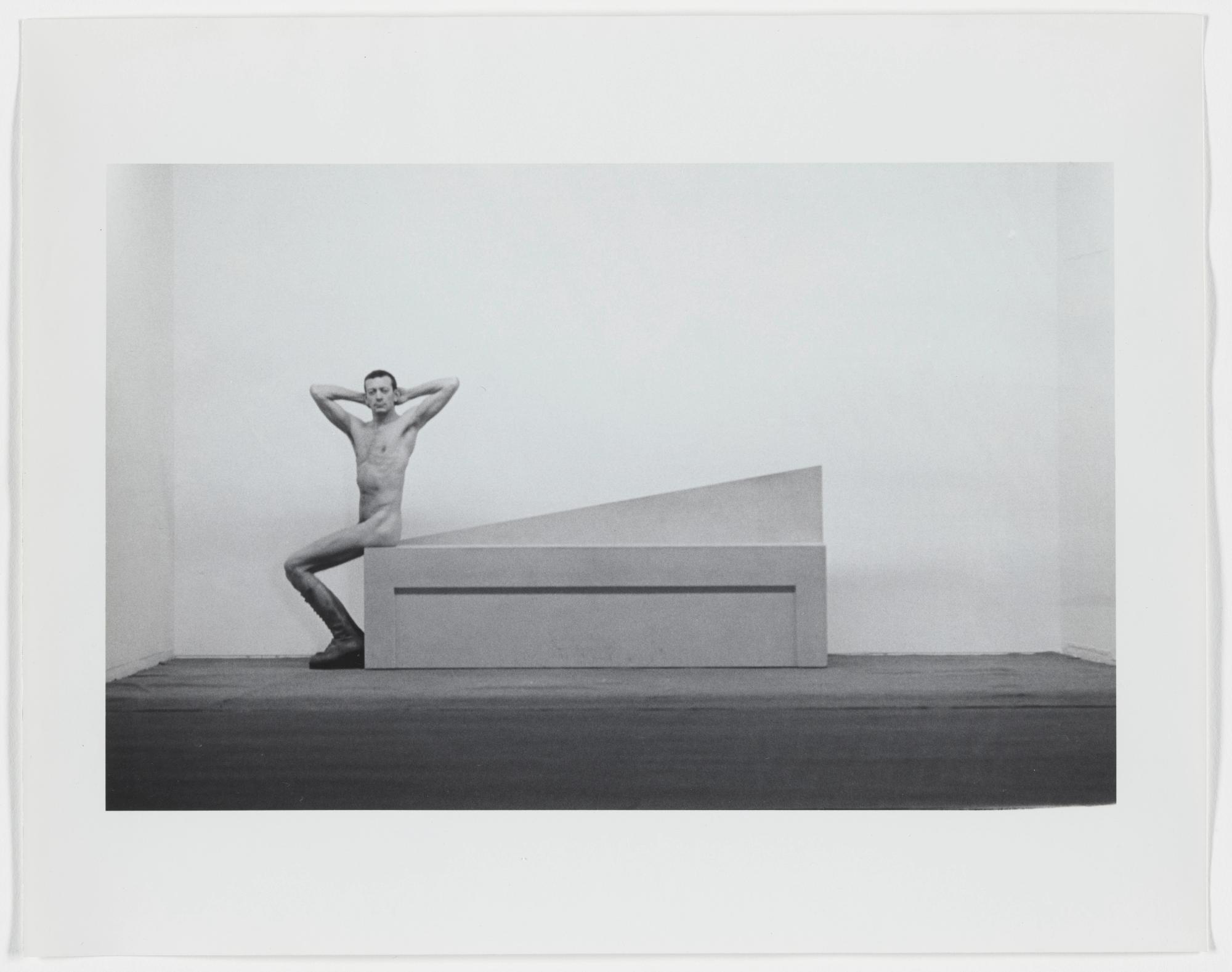

Shape Shift was the largest exhibition of the artist’s work in the United States since his death, and devoted an entire gallery to Burton’s pioneering performance practice, with photographs, notational sketches, and an unassuming wooden stool once used on stage. In his stagings, pieces of furniture weren’t mere props — they defined the actors’ social relations. He even transformed some into performers themselves, with lights coming up on chairs in different configurations to represent group dynamics — no actors required. The use of objects as performers is a heightened take on minimalism’s use of placement, form, and volume to activate one’s spatial awareness. Evoking the surfaces on and around which we live, like tables, chairs, and the floor, minimalist sculptures’ horizontal planes are often subject to unintended use (this year, I have seen a bag set down on a Jackie Winsor cube and a jacket slotted into the gap of a Donald Judd wall stack). Burton’s sculptures affirm this impulse, allowing themselves to be structures of support, fostering physical intimacy between sculpture and viewer.

Individual Behavior Tableaux, choreography note, ca. 1980; 91.3x5 in. Scott Burton Papers, II.

Scott Burton, View of Individual Behavior Tableaux, as performed by Kent Hines, 1980, gelatin silver print, 20 × 25 cm. Courtesy: © Estate of Scott Burton/ Artist Rights Society (ARS), New York, © The Museum of Modern Art/Licensed by SCALA /Art Resource, New York

Scott Burton, Study pose for Individual Behavior Tableaux included in “Documenta 6,” 1977; polaroid; 4.25x3.5 in. Scott Burton Papers, II.75.

Scott Burton, Installation view of Furniture Landscape courtesy of the MoMA.

Later, Burton would also design his own furniture, displays of which formed the core of the Pulitzer exhibition. Instead of a traditional decorative arts presentation with chairs lined up against a wall, the show’s curator Jess Wilcox decided to group them in cliques, conspiring with one another and highlighting Burton’s large material vocabulary. Made of wooden slats, curved steel, formica, and blocks of solid stone, each piece is bestowed with a distinct personality, allowing them to form relationships with one another. Like the studied movements of his performers, these sculptures “perform” being chairs in an uncanny, mannered way.

Photography by Alise O'Brien courtesy of the Pulitzer Foundation

Photography by Alise O'Brien courtesy of the Pulitzer Foundation

Photography by Alise O'Brien courtesy of the Pulitzer Foundation

Photography by Alise O'Brien courtesy of the Pulitzer Foundation

While seeing Burton’s work in a museum setting is impressive, some of his most significant works couldn’t even be shown there. As he developed his sculpture practice, his ambitions grew larger, and he took on numerous public commissions and began to create comprehensive urban environments. His last and largest project is the five-acre Waterfront Plaza (1989) in lower Manhattan, designed collaboratively with the artist Siah Armajani, architect Cesar Pelli, and landscape architect M. Paul Friedberg. The plaza stitches together the soaring atrium of Pelli’s Wintergarden and the Hudson River, with two arms reaching into the water to enclose an angled rectangular marina. Two stepped granite tiers line the perimeter of the building, set back to create a string of raised dining terraces separated from the busy lower plaza by a band of waist-high, shimmering waterfalls. These tiers expand into the lower plaza through eleven repeating sculptural vignettes, with an old-fashioned lamppost standing on the lowest tier above three granite forms on the plaza’s pavers — two low sets of steps flanking a wide cylindrical drum, rising to the middle. Beckoning the public to sit or stand on them, Burton’s pedestals transform people into living statues. Overlooking the water sits a supersized circular settee in granite, a large column rising from its center with a deco-like flared lantern at the top, echoing the Statue of Liberty’s torch visible in the distance. Evoking an obelisk in a piazza, this beacon is one of Burton’s most monumental designs and a testament to his passion for history’s most enduring public urban spaces.

Photography by Alise O'Brien courtesy of the Pulitzer Foundation

Photography by Alise O'Brien courtesy of the Pulitzer Foundation

Photography by Alise O'Brien courtesy of the Pulitzer Foundation

Photography by Alise O'Brien courtesy of the Pulitzer Foundation

This work of Burton’s final years never faded from public view; it quietly became the scenery of our lives. However, in 2022, as part of an initiative to raise the shoreline to prevent flooding, Bjarke Ingels Group was commissioned to “reimagine” the plaza. While other segments of the plan retain existing designs and surgically add flood barriers, Burton’s artwork is due to be razed, replaced with curved seating and grass banks resembling Hudson Yards or Little Island. A paradox of permanence haunts Burton — his most solid and visible works are disposable while dormant pieces in museum storage can reemerge through efforts like Shape Shift. One of the striking things about the Pulitzer Arts exhibition was its framing of Burton not as a marginal figure finally getting his due, but as one of America’s prominent voices in design abandoned by the institutions that supported him during his life. Slipping between art and design, his work challenged these categories and wound up lost, sliding in the cracks between them. As his work finally begins to receive renewed attention, it is shameful that this last, largest piece, designed by a gay man dying of AIDS right in the heart of the crisis, is due to be so casually discarded. Go spend some time there before the wrecking ball comes. We need art like Burton’s, art that asks fundamental questions about how we relate to one another.

Photography by Oscar Peña for PIN–UP

Photography by Oscar Peña for PIN–UP