A NEW CARTOGRAPHY OF INTIMACY

Meet Blake Gallagher, the Architect Who Built Sniffies

by Michael Bullock

Blake Gallagher photographed by Daniel Trese for PIN–UP.

Blake Gallagher doesn’t cruise. He codes, building the platform that lets others do it better. A former architect turned tech founder, Gallagher is the quietly compulsive mind behind Sniffies, the real-time queer cruising app that maps desire across physical space. Since its launch in 2018, the platform now draws close to 1,000,000 daily users and a near-religious following among those for whom sex is less about secrecy, more about strategy. Despite its explosive success, Gallagher has remained largely unseen: the anonymous host behind the map.

Gallagher grew up in San Diego in the 90s in a quieter, more controlled version of the clichéd freewheeling California of lore: think subdivisions, strip malls, desert air. Military families. Polite repression. In a city that projected openness while enforcing conformity, boys like him didn’t exist — or at least it felt that way.

He studied structural engineering and went to grad school for architecture, then spent 14 years shaping spaces where strangers navigate rules, authority, and vulnerability: airports, hospitals, courthouses, and high-rise residential towers. The experience gave him a critical view of how people encounter one another in public. All the while, he was busy building a side project: the first version of Sniffies. He framed it as a question of interface: Could a social network be mapped onto real space? He folded together psychogeography, urban theory, and his own gay experience. What emerged wasn’t just an app — it was a spatial proposition. Cruising, reimagined. Visibility, proximity, and risk, rendered in real time.

Of all the apps to follow in the wake of Grindr’s 2009 debut, Sniffies is the first with a real shot at challenging its dominance, even amid its current fight to get back on the Apple Store (in mid-May, Apple removed Sniffies for “ongoing content restrictions.”) It isn’t just the interface or branding that sets it apart — it thrives by breaking from Grindr’s conceptual DNA in two crucial ways. First, it rejects the “love is love” respectability politics that shaped early gay tech, with those benchmarks of assimilation — dating, marriage, monogamy — that ultimately sanitized how its users expressed desire. Sniffies centers the uncensored pursuit of carnal pleasure. Instead of curated profiles, it offers the goods directly.

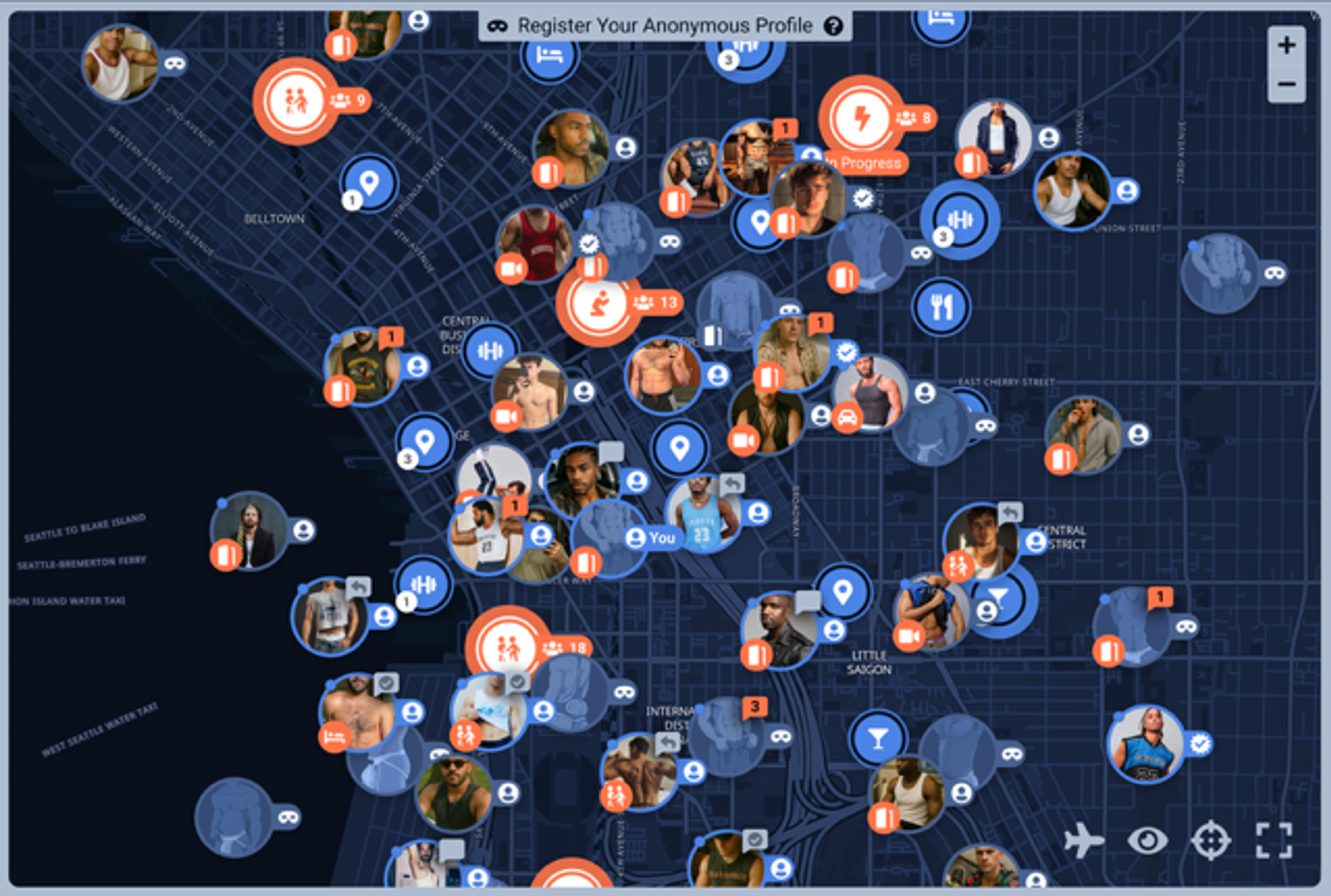

An example of the Sniffies map. Courtesy of Sniffies.

Second, where Grindr and its copycats flattened queer intimacy into an endless feed, Sniffies re-inscribed it onto the fabric of our cities and towns. Gallagher introduced a subtle but seismic shift. Sniffies doesn’t re-closet sexuality. It begins with the premise that any space can be queer space, and shows its users — through elegant audacity — that the streets they move through already hold that potential. It doesn’t seek to replace analog cruising, but rather supercharges it, adding digital velocity to something ancient and embodied. It makes sense that a gay architect was needed to reclaim what other tech entrepreneurs had accidentally erased: the physicality of gay space.

An image of Gallagher is beginning to emerge — a shadowy, latter-day Hefner, a digital libertine presiding over a pleasure empire of his own design. But like an architect crafting fantasies he doesn’t fully share with his clients, he seems to have built a world he doesn’t entirely belong to. Gallagher champions a sexual revolution — ideologically, professionally — but whether he partakes in it personally remains unclear. Ironically, the man who put everyone else on the map is too private to place himself.

Photography by Daniel Trese for PIN–UP.

Michael Bullock: Before Sniffies, what were your early experiences with cruising? What was your original perspective on that kind of activity?

Blake Gallagher: I didn’t encounter cruising in my adolescence. I grew up in San Diego. I was born in the 80s but came of age in the 90s. The world was a different place — especially when it came to sexuality. Southern California, and San Diego in particular, was more conservative than people might assume. In my community, sexuality wasn’t something people talked about. When you’re a kid trying to make sense of the world, you don’t even have a concept of sexuality yet — let alone the idea that you might fall on some spectrum. At some point you realize: not everyone’s experiencing this the same way you are. That’s when the search begins. For me, it was about finding others like me.

When you realize your sexuality is different from your parents and your peers, the search for people like you isn’t a choice — it’s a drive.

Totally. The need to search, to identify. And once you start looking, you begin picking up on signals — codes that have evolved out of necessity. For most of modern history, queer people had to exist in silence, so we developed a covert language — vocabulary, mannerisms, and other ways of finding each other. Codes became our cultural shorthand.

When I was a teenager, I assumed being gay meant being an outlaw. That was the shape it took — furtive glances in mall bathrooms, coded looks at highway rest stops. What I didn’t understand then was that public sex wasn’t just about being deviant — it was logistical. The suburbs offered no space for connection, so gay people have always repurposed what’s available. You’re forced to adapt. If you ask for permission, you won’t exist.

Exactly.

So then — architecture. You studied that in undergrad?

I did my undergrad in structural engineering, actually. But I was always on the path toward architecture. I went on to grad school at the University of Washington in Seattle. That program was really formative, especially one professor, Nicole Huber, who was deeply invested in urban theory. I hadn’t thought much about urban design before I met her. She opened my eyes to how architecture exists within broader systems. That idea — that buildings don’t exist in isolation — completely changed my outlook. I practiced architecture for about 14 years, mostly on large-scale commercial projects. Few buildings are designed for just one person. Architecture almost always shapes how people interact. It choreographs behavior.

What kind of projects specifically?

A whole range. I was lucky not to be pigeonholed. Airports, hospitals, courthouses, high-rise residential towers, showrooms, briefing centers — pretty much everything. And in each case, the question was: how does this space shape human interaction? Because every type has its own needs, but at the end of the day, it’s still people occupying it. It’s still about behavior. What became really interesting to me was how urban environments enable or disrupt spontaneous, serendipitous interaction. In a city, you’re a stranger among strangers. You might engage transactionally — with a cashier, a waiter, a cab driver — but real engagement happens when something breaks the script. And I became obsessed with how design can allow for that spark.

Sniffies was obviously built with those ideas in mind — urban design, serendipitous encounters, systems of movement, and proximity.

Yeah. Urban environments generate chance moments. Catching someone’s eye on the street. That energy is what Sniffies tries to recreate.

Have you read Samuel R. Delany’s book Times Square Red, Times Square Blue?

I haven’t.

Delany writes a love letter to Times Square before Giuliani unleashed Disney on it. He talks about the value of cruising there — how it fostered cross-class contact, which for him, led to intimacy and understanding. He applied Jane Jacobs’s “eyes on the street” theory — that regular people watching each other on the street creates a safer, more vibrant community — to cruising culture.

I need your reading list.

I’ll share it.

One design principle that really informed Sniffies is “prospect and refuge.” It comes up a lot in architecture and urban theory. Basically: spaces are most comfortable when they let you toggle between exposure and protection. Think sitting at a cafe with your back to the wall, tucked in, but still able to see the plaza. That’s refuge. Standing on a hill, surveying everything around you — that’s prospect. Good spaces let you do both.

And Sniffies brings that into the interface.

Exactly. It lets users decide how exposed they want to be. You can post to a 30-mile radius or DM one person. You can randomize your location. You can join groups or just lurk. The controls let people move between exposure and retreat.

Grindr is literally a vortex.

Right. A grid is one-dimensional — just a line of people by distance. A map is two-dimensional. That visual context — people in relation to you — creates a topology. It reveals subgroups. You don’t get that from a list or feed. Those flatten people. On Sniffies, you’re not just near others — you’re among them.

Blake Gallagher photographed by Daniel Trese for PIN–UP.

Sniffies introduces a subtle but profound psychological shift. The solicitation of a partner isn’t confined to an app or fantasy zone — it’s mapped back onto the actual world. Sniffies doesn’t stash sexuality in a virtual closet. It starts from the premise that any space can be queer space. It tells its users: the whole world is yours.

When you see someone on the map, at a real geographic point, you’re reminded this is a person sharing space with you. Zoom out, and you notice clusters. You realize you’re not alone. There are others, just blocks away.

You get a building-by-building sense of how gay your neighborhood really is.

Totally. And it encourages exploration. You might spot a pocket of users and think: what’s happening over there? Suddenly you’re walking around a new neighborhood. The app pulls you back into your body, into the world. Unlike a static list, the map moves. Users drift in and out. It’s alive. It builds memory. You know where something happened, and how to return.

And the presentation of self on Sniffies is radically different. It’s not polished. It’s stripped down to a primal shorthand of need.

Right. There’s a visual language. You learn to read the map — who’s hosting, what’s happening. It’s like nonverbal communication. Like cruising in real life — gesture, vibe, code.

Bringing those subliminal, pre-verbal aspects of cruising into a digital interface saves everyone so much time. Thank you.

There’s also something mythic about it. Think of all those utopian renderings of cities — flying machines, sci-fi skylines. There’s always been a fantasy of seeing the world from above. Sniffies lets you do that with sex. You lift off the sidewalk and see desire as a spatial system. It’s primal and futuristic at once.

That overview gives you a sense of control — maybe artificial, but satisfying. You see individuals not as fragments, but as a whole. It shifts how you think about scale.

Exactly. That impulse is ancient. Even cave paintings offered overhead depictions of hunting scenes. We’ve always wanted to understand systems from a higher perspective. Sniffies lets you zoom out and see a community in motion, in context. A kind of scale you don’t get from a feed.

Tagline: Sniffies: A God’s-eye view of desire… So, how did this begin?

It wasn’t a business idea. I’d been working as an architect, but at night I taught myself to code. Coding became a puzzle — translating an idea into an interface. I was playing around with mapping APIs around 2015. One day, I passed a guy on the street. We made eye contact. And I thought: why can’t I open a map and say, “Hey, we just passed each other.” Not a list. Not a grid. Something spatial. That was the seed. I built a prototype, launched it in Seattle, and people started using it.

Sniffies doesn’t share exact locations, right?

No. Everyone’s location is randomized in a way that can’t be reverse-engineered. There are also privacy settings so you can adjust the blur.

So, this wasn’t: “How do I build a better Grindr?”

No, it was “How do I solve this feeling I had on the sidewalk?” That street encounter became the use case. I didn’t want to improve something else — I wanted to start from scratch. I built toward what was missing. Turns out there was a vacuum, but I didn’t set out to fill it.

When did it start to feel viable?

Almost immediately, when I launched the early version in Seattle. It was free, hyper-local. But when people kept returning, I started seeing the potential. I began thinking of it as a serious project — maybe even a life’s work, at least for this chapter.

There’s a rumor it started as an underwear trading site?

Yeah, I’ve seen that. The story is it began as a used underwear and sock marketplace. Totally false. But it’s funny how persistent it is.

So where did the name come from?

Much less exciting. I had a list of short domains that I purchased for other concepts. When the project reached a point where it was ready to go live, I needed to choose a domain so people could access it. I scrolled through my list and one of them was sniffies.com. I kept looking for something more obvious, but nothing was left. Eventually, I realized: sniffing out an encounter is exactly what Sniffies does. It works.

Blake Gallagher and Sniffies Chief Marketing Officer Eli Martin and photographed by Daniel Trese for PIN–UP.

So even as an adult, I’m getting a sense that your own relationship with cruising wasn’t particularly substantial?

I would say, normal.

What would you consider normal?

My relationship to cruising was — and still is — less about the act itself, and more about the parts centered on finding people who were otherwise invisible to me. Even as society has opened up, and queer people have become more visible, there’s still a real need for us to find each other. I also think there’s less of a need for that connection to be exclusively sexual. Physical cruising spots still matter, and Sniffies has shown that the essence of cruising can be translated digitally. But the digital and analog formats rely on each other. Sniffies is geo-referenced — it’s tied to physical space. It still points people toward venues: bars, bathhouses, gyms, clubs. Maybe the app increases the chances of a real encounter. Maybe it pre-arranges something that would’ve once been left to chance. Either way, the physical and digital complement each other in a powerful way. This digital version of cruising lets our community find itself — connect with itself — on a different scale than physical cruising ever could.

In 2016, architect Andrés Jaque — now the dean of Columbia’s architecture school — made Intimate Strangers, a documentary about Grindr that argued the app had directly contributed to the closure of many of London’s gay venues. The film was shown at the London Design Museum. It historicized what most queer people already felt: in the beginning, apps really did seem to be replacing bars, cruising grounds, and whole nightlife cultures. What’s striking is that Sniffies seems to be restoring something rather than speeding up that erasure. And it’s telling that it took an architect to design a digital space that gives something back to the physical world.

Yeah. I think any community needs to be in the same place at the same time, at some point. We’ll always need physical spaces for that to happen. But we’ll also always need digital spaces that support those connections. And for a while, we had neither. The early digital platforms didn’t solidify community — they isolated us from it. And at the same time, they were pulling energy away from our real-world gathering spaces.

And creating a kind of distortion — where the performance of self became so dominant that reality started to feel out of reach. Especially for a generation that grew up entirely online.

Exactly. When it becomes about showing an idealized version of yourself, it can actually become hard to interact at all. What we’ve tried to do with Sniffies is create a structure where people can find one another without having to over-curate themselves. It’s not anonymous in the way older apps were, but it’s not overly performative either. There’s room for curiosity, for proximity, for serendipity.

It seems like Sniffies lets users present the wilder sides of their sexual identity without pretense — it’s not something abstract or internal, or something divulged after hours of back and forth.

Right. We’re demonstrating to each other, in real time, that there are creative, valid ways to be sexual and visible. And that those ways can be shared. They don’t have to live in shame, or in the dark, or behind closed doors. You’re not just seeing yourself — you’re seeing other people with your specific kinks. There’s power in that.

Cruising IRL before Sniffies required work. You had to know where to find it, and if you engaged in it, it was usually unspoken. I think Sniffies, combined with PrEP, has done a lot to shift its perception. I now meet so many guys in their 20s who embrace it as part of their identity, and as part of gay history.

Those spaces were often stigmatized or pushed to the margins. Sniffies says: forget that. This is who we are — and we’re going to show it, grounded in place. That’s the breakthrough. When you see this sexual culture not as othered but as integrated into real neighborhoods, real streets — it’s humanizing.

And maybe not just for queer people.

Exactly. If you zoom out and think about the broader crisis of digital discourse — how anonymous and disembodied we’ve all become — there’s something meaningful about tying identity back to space. What if every profile were grounded in place? Maybe that’s what it takes to rehumanize how we see each other.

Have you brought the project back to your original professor?

I did, actually. I ran into her [Nicole Huber] at a memorial a couple years ago. We hadn’t spoken in years. I told her about Sniffies — what it had become — and I thanked her for the principles she instilled in me, about how space shapes society. They really did influence what I ended up building. She seemed touched. I think most teachers hope their work ripples outward like that.

And now you’ve built something that’s shaping the culture. What have you heard from users that’s really stuck with you?

It’s the unexpected depth. You start with what feels like a fleeting need — but I hear again and again: “I met my boyfriend on Sniffies,” or they meet their best friends. Long-term relationships develop from brief encounters. And that means a lot. That wasn’t something I anticipated, but it’s meaningful. That part feels like a gift.

You’ve implied that this platform is about broader visibility.

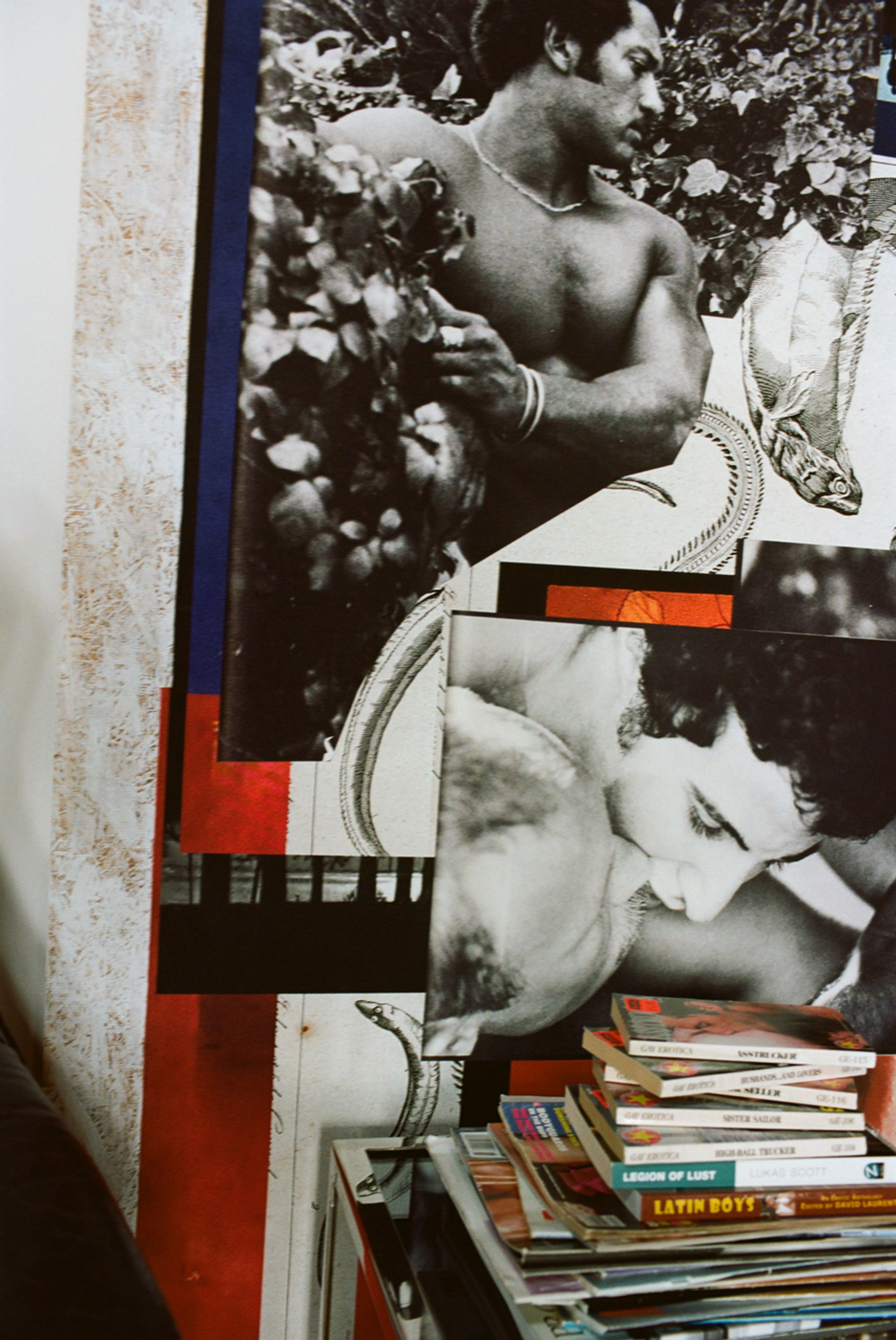

Right. We’re building a culture, not just a product. And you can see that in everything we do — from the design to the merch to the campaigns. People wear Sniffies gear and they’re saying: I cruise. I’m proud to cruise. It’s public. It’s normal. And maybe even beautiful. From the beginning, Eli Martin, our Chief Marketing Officer, has tried to create an imaginary of what an openly sexual society might look like. Not by spelling it out, but by presenting a world that feels free enough for people to project their own fantasies, identities, and fetishes onto it. We leave just enough detail for the viewer to make it their own. Back when the platform was just starting to take shape, I realized I had a specific vision for how I wanted to communicate what Sniffies could be — something playful, open, non-apologetic. Eli was the only person I knew who could bring that to life. He understood the culture, but also had the imagination and marketing instincts to build something new from it. A lot of what makes Sniffies what it is — its visual language, its tone, its refusal to explain itself — is because of him. From the very beginning, our goal was to depict a world of sexual freedom, not define it. The imagery invites interpretation. It’s erotic but ambiguous, designed to let people project their own desires onto it.

So, my last — and maybe most important — question: given your training, your politics, and your platform’s reach — when are you going to give New York City the legendary gay bathhouse it deserves?

Talk to Eli about that. That’s his dream.

And when Sniffies becomes a physical space, what will it be?

It will need to follow the same spatial logic. Prospect and refuge. Circulation and retreat. The best spaces — clubs, bars, cruising grounds — allow you to orbit, to observe, to take a lap. It’s the architecture of potential. That’s what creates the conditions for connection.

Any favorite bathhouse you’d like to cite that does it well?

No comment.

Blake Gallagher photographed in the Sniffies boardroom by Daniel Trese for PIN–UP.