Sam Chermayeff photographed by Nadine Fraczkowski for PIN–UP 39.

Sam Chermayeff photographed at home, sitting on a swing and surrounded by his children’s toys, at Baugruppe Kurfürstenstraße 142, a set of semi-communal apartments he designed in Berlin. Portrait by Nadine Fraczkowski for PIN–UP 39.

However much he rebels against it, Berlin-based architect and designer Sam Chermayeff maintains a reverence for Modernism — or at least the stranger strands of it. “I often think of architecture as this universal thing in a Modernist way. But then it’s fascinating to me how that universalism is individualized,” he says of the way people customize their spaces. “Understanding that balance feels like the key to a lot of things.” His projects span scales from lighting, seating, and interiors to housing developments like the Berlin Baugruppe where he lives, a forthcoming six-bedroom home in Rockaway, New York, and a planned mixed-use development in Tirana, Albania. Each time, a freedom of form meets an insistent, if defamiliarized, rationalism. Why should stoves and sinks be 3 feet above the floor and facing a wall — wouldn’t it be better if you could sit and chat with friends as you cooked? Cars take up so much public space — why should they be private? And, speaking of privacy, is that maybe overrated? In his projects, which he has developed through two firm — first June 14 Meyer-Grohbrügge & Chermayeff and now Sam Chermayeff Office — the architect poses questions with a confidence that assures you he’s already found the answer. Even if you’re skeptical at first, you’ll soon be nodding along.

At every scale, his ideas question how design systems, individuals, and groups act on one another, and how they can act differently. Lately, this has required a bit of anthropology, with Chermayeff, who cut his teeth at SANAA in Tokyo, inviting himself over to friends’ and acquaintances’ houses to cook in a bid “to figure out how other people live.” This research has fed into his work on kitchens, of which he’s designed over a dozen, with features such as exposed plumbing, stovetops turned askew, or compact ovens rising to eye-height upon spindly legs. By decoupling these essentials from counters, walls, and the strictly orthogonal, he creates “free kitchens” in which new uses emerge. “I never put things against the walls. I don’t have built-in closets,” says the 44-year-old, who trained at the University of Texas and London’s Architectural Association. “I want to see under it, and I want to see the wall behind it. I have an obsession with that.”

Baugruppe Kurfürstenstraße 142. Photography by Oliver Helbig.

Sam Chermayeff photographed by Nadine Fraczkowski for PIN–UP 39.

Sam Chermayeff photographed by Nadine Fraczkowski for PIN–UP 39.

Other Chermayeff projects reconstruct what elsewhere he’s broken to pieces: the 2023 Triangle Kitchen, the first iteration of which he designed for a Berlin apartment, comprises a metal structure with a dishwasher, fridge, and cabinet space on two of its sides. It also features burners and a sink on separate edges, plus a draining tray that can be used to grow plants. The kitchen condenses an entire room into a single apparatus that encourages interaction when socializing and simplifies usability when solo. The shape recurs in Chermayeff’s 2014 Triangular Bed, which he designed with his former partner Johanna Meyer-Grohbrügge. Shaped like a pizza slice, the mattress — which comes with custom pillows and sheets — is calibrated to human dimensions (feet are narrower than shoulders) and encourages a playful attitude in sleepers of all ages. “You make peace with the fact that on the very same spot you might have an orgy one day or simply cuddle up with a few of your kids the next,” he explains. The architect has a Triangular Bed in his own apartment at Kurfürstenstraße 142, in the Baugruppe building that June 14 Meyer-Grohbrügge & Chermayeff completed in 2022. Consisting of a semi-communal arrangement of six overlapping towers, the 21-unit complex reflects its collective ownership: hallways and units aren’t strongly distinguished; you can readily see into other apartments from both within and from the street unless curtains are drawn; and the entire building can, in theory, be opened up internally. The owners decide how living together looks — a balance between the individual and the collective that Chermayeff sought to redefine, since for him, privacy is a fetish of developers. “I don’t particularly need quiet alone time,” he notes. “Does anyone? Where do those ideas come from?” Answering his own question, he suggests they relate to traditional organizations of labor and the family, including distinctions between work time, free time, and domestic roles, as well as Modernism’s perpetuation of them.

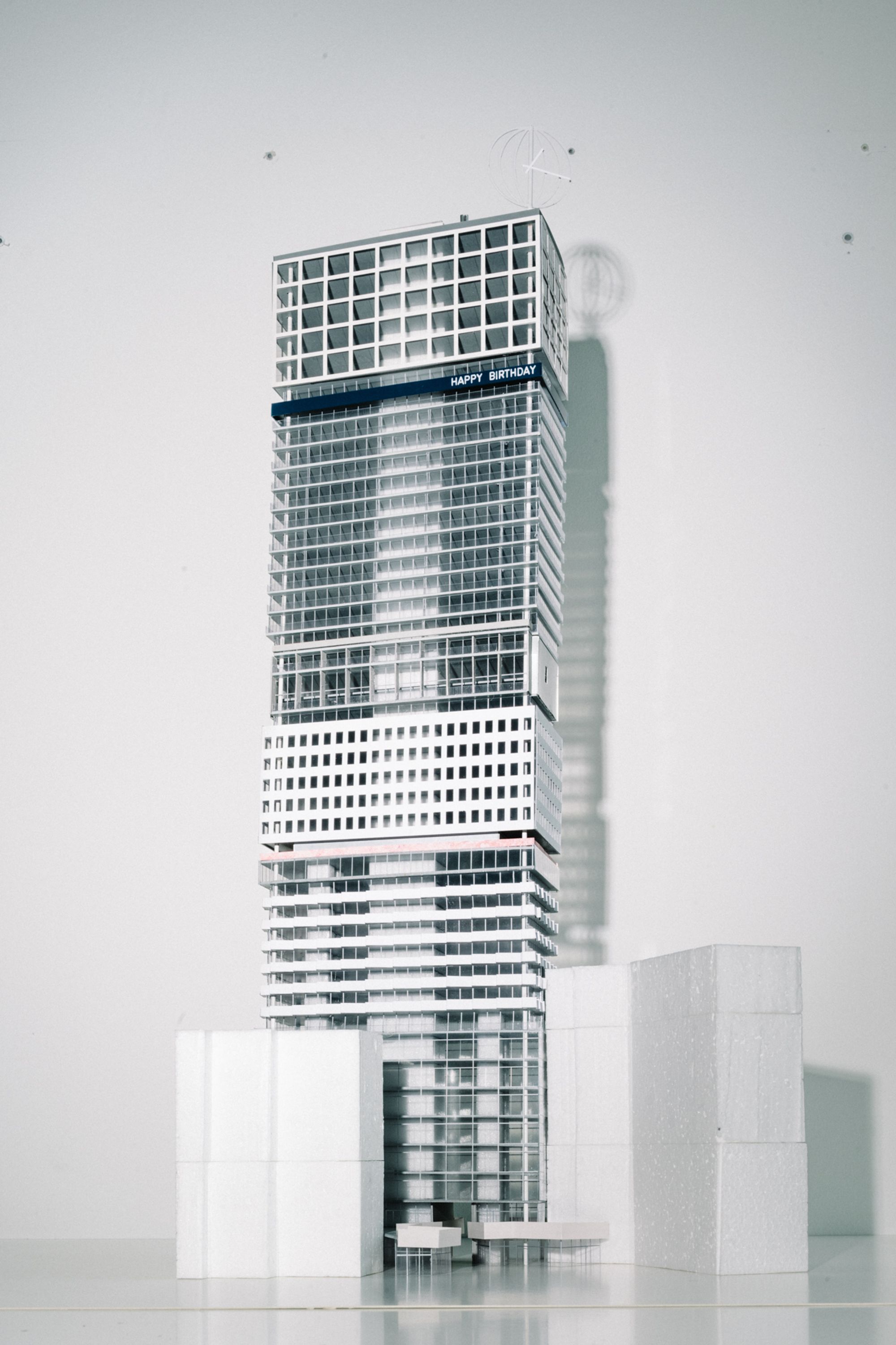

Sam Chermayeff designed Sun Moon Star, a planned 44-floor development in Tirana, Albania, envisioned as a “timeless, everyday” landmark. This 1:200 model highlights the building’s juxtaposed Modernist forms, with distinct sections flowing from penthouses at the top to apartments, a restaurant, a hotel, and offices below. Photography by Oliver Helbig courtesy of Sam Chermayeff Office.

1:200 model of Sun Moon Star by Sam Chermayeff Office. Photography by Oliver Helbig courtesy of Sam Chermayeff Office.

1:200 model of Sun Moon Star by Sam Chermayeff Office. Photography by Oliver Helbig courtesy of Sam Chermayeff Office.

Portrait by Nadine Fraczkowski for PIN–UP.

There is something very personal in this decoding of the 20th century’s architectural legacies. Chermayeff was born in Manhattan to Ivan Chermayeff (1932–2017), the graphic designer responsible for the logos of NBC, the Museum of Modern Art, New York City, and PBS. Noted aquarium architect Peter Chermayeff is his uncle. And his great-grandfather is Russian-British architect Serge Chermayeff (1900–96), author of influential Modernist books such as Community and Privacy: Toward a New Architecture of Humanism (1963, with Christopher Alexander) and Shape of Community: Realization of Human Potential (1971, with Alexander Tzonis). Chermayeff Jr.’s fascination with domestic spaces, he says, has much to do with the apartment he grew up in, as well as with his parents’ division of labor — typical New Yorkers of a certain class, neither of them cooked.

With Triangle Kitchen (2023), designed for Nicolas Hagius’s Berlin apartment, Chermayeff strategically placed stove burners and a sink across a protruding corner, encouraging socialization and interaction while cooking. Photography by Oliver Helbig.

Chermayeff and Maharam’s Tent Typologies (2024), shown at Dropcity during Milan Design Week, play on the ancient form of the hanging roof to create a series of structures both permanent and ephemeral. Photography by Jeroen Verrecht.

Designed and produced alongside the specialized Berlin metal studio ErtlundZull, Chermayeff’s Tiny Stove Table (2018) transforms a design object into a functional kitchen, featuring a customizable stainless steel gas burner built into the table’s surface. Photography by Jeroen Verrecht.

June 14 Meyer-Grohbrügge & Chermayeff’s Free Kitchen (2015) series is a malleable, expandable set of kitchen equipment, including a free-standing sink and toaster, that upholds methodological living while granting freedom of space. Photo by Oliver Helbig courtesy Sam Chermayeff Office.

June 14 Meyer-Grohbrügge & Chermayeff’s Free Kitchen, 2015. Photo by Oliver Helbig courtesy Sam Chermayeff Office.

Sam Chermayeff, Street Light, 2018. Photography by Oliver Helbig courtesy Sam Chermayeff Office.

Sam Chermayeff, Open Sofa, designed for BD Barcelona, 2023. Photography by Oliver Helbig courtesy Sam Chermayeff Office.

Chermayeff’s designs often toe the line between standardization and customization, between private and public space, whether in subtler formal arrangements or in more direct iconicity. A 2018 piece, Street Light, mounts a curvaceous, full-scale municipal road lamp through a powder-coated steel table — like a heavy-duty remix of the Castiglionis’ Arco. Other projects, like the Open Sofa for BD Barcelona, function as a bench-as-platform, with bases, backrests, armrests, tables, and the like that can be rearranged at will. Whether developed with design stalwarts like BD or Maharam or made as custom projects — such as the Juice Bar (2022), a plinth-mounted household blender paired with a log that serves as both chopping board and parasol holder — Chermayeff’s objects demonstrate an insistent awareness of their end user while taking on a life of their own. He calls these creations “creatures” or “beasts,” and has noted that they’re a bit like pets. “They’re body-related typologies,” he says — put them all together and it’s “a little bit like an animal farm.” Still, Chermayeff is far from opposed to the mechanical. He’s an auto aficionado and has staged multiple off-kilter projects with cars. In 2022, Saunarider, a collaboration at Berlin’s KW Institute with art-fashion-design mainstays BLESS, saw a champagne-colored Mercedes-Benz S-Class transform into a sauna with a wood-en-bead interior, while at the 2023 Salone del Mobile in Milan he put on the exhibition Cars and the Public Joy. Created with Berlin collaborators including Andrea Caputo, BLESS, and New Tendency, the show featured automobiles and a motorcycle that had undergone quirky design hacks: an icebox cooler in the boot; a suction-cup lounge chair on the hood; that sauna again. Private vehicles that take up so much public space proposed themselves as Swiss-Army knives of furniture functions, colliding a whimsical attitude with a high-precision design idiom.

This illustrates an impulse running through Chermayeff’s work — from car-sculptures to deconstructed buildings and interiors to hybrid beasts and creatures: the imagination to see beyond what’s treated as “given,” and to cast aside architectural standards in order to liberate how we function in relation to our stuff and spaces.

In 2022, Chermayeff collaborated with design studio BLESS to make Saunarider, unveiled at the KW Institute for Contemporary Art in Berlin. The project transforms a Mercedes-Benz into a mobile sauna, its interior lined with wooden beads. Photography by Oliver Helbig courtesy Sam Chermayeff Office.

Chermayeff and BLESS’ Saunarider at the KW Institute for Contemporary Art in Berlin. Photo by Oliver Helbig courtesy Sam Chermayeff Office.

Sam Chermayeff photographed by Nadine Fraczkowski for PIN–UP 39.