Marva Griffin’s Milan apartment. Photography by Stefan Giftthaler for El País, Spain (2022).

Marva Griffin photographed by Jeremy Liebman for PIN–UP.

Marva Griffin Wilshire is the godmother of Italian design. Since arriving in Milan in 1971, the Venezuelan-born polyglot has made herself a key player in the famously hermetic northern-Italian metropolis. She got her start 50 years ago as the assistant to Piero Ambrogio Busnelli, the charismatic cofounder of B&B Italia, a veritable baptism by fire (stories of the mercurial Busnelli are Italian design lore). For three and a half years she gained experience working closely with what was then the new guard of Italian architecture and design: Mario Bellini, Vico Magistretti, Renzo Piano, Richard Sapper, and Marco Zanuso, to name but a few. A natural communicator, Griffin then moved on to Condé Nast, working on titles such as Maison & Jardin, Vogue Décoration, House & Garden, and Vogue US, establishing herself as an inescapably elegant force in the fashion and lifestyle media landscape. But what Marva Griffin is best-known for today — and what she considers her most rewarding professional achievement — is her role organizing Satellite, the showcase for young designers at Milan’s Salone del Mobile. Griffin, an optimist by conviction, founded Satellite in 1998, after becoming Salone’s director of international press. In the 25 years since, over 14,000 designers have shown their work under the program, many of them moving on to make lasting contributions to the world of design (to this day some of them refer to Griffin as “la mamma”). Though she’s been recognized with a gold medal from the city of Milan, Griffin’s career has also been shaped by her international outreach and experiences. As a pioneering woman and key figure in the evolution of design production and communication over the past 50 years, we thought it was important to connect Griffin with Michelle Joan Wilkinson, one of the foremost design and architecture experts in the U.S. and the curator for architecture and design at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, D.C. The result is a conversation between like minds, across continents, about all things design, heritage, community, and the importance of “the whole story.”

Marva Griffin and Michelle Joan Wilkinson were photographed at the Peninsula Hotel, New York. Photography by Jeremy Liebman for PIN–UP.

Michelle Joan Wilkinson: To frame our conversation, I’ll share a little bit about my own background. I was born in Brooklyn, but my mother is from Guyana, so in that sense we’re neighbors, since Venezuela is right next door. As a child I went to live in Guyana for five years with my grandparents, in a house my grandfather had designed and built in the 1950s. The house held a lot of memories for me that much later kept pulling me back to thinking about space, architecture, and design. Reading about your upbringing in Venezuela, and your memories of rearranging furniture in the house as a child and buying interior-design magazines as a teen, I started to feel this sort of kinship regarding how our earliest experiences sometimes shape where we want to go in life. So I would like to go back to Venezuela and hear about your childhood.

Marva Griffin: I grew up in El Callao, a small town in eastern Venezuela. We had a very large home in a small place, more like a village. It’s where the goldmines are. When the gold was discovered, in 1871, many people from the Caribbean islands came to El Callao. That’s why it’s one of the few places in Venezuela where there’s a strong Black population. And with the wars many Europeans also came to El Callao, which is why you’ll see little Black children with blue eyes, because the father would be Italian, French, German, or whatever. It was a very cosmopolitan place in the 40s and 50s.

What did your father do?

Because of the mining, most people worked in jewelry shops. My father had one that he ran with his son from a previous marriage. He also ran the four cinemas in El Callao, so he would always travel to Caracas to pick all the good films. Every weekend, if we behaved, we had free entrance to the movies.

I was reading about the 100-year-long carnival tradition in El Callao.

Yeah, but I hated it. They have this media pinto character, people covered in black paint, and they would touch you and the paint would rub off, and then they would throw white flour. I remember one year I was hiding in my grandmother’s room and she inadvertently locked me in her closet. I was screaming “Abuelita! Abuelita!” until finally someone found me. So I really hated carnival in El Callao. [Laughs.]

How many siblings did you have?

We were five girls and three boys, so eight in total. I was among the younger ones, along with my brother Héctor and my sister Elena. In the early days, El Callao only had elementary-school education, so my older sisters and brothers were sent to Caracas for high school, and later to Trinidad. By the time I was old enough, El Callao had a high school, but I was still sent to Trinidad, to boarding school at St. Joseph’s Convent in Port of Spain and later to San Fernando. My mom had a sister who was married and lived in Trinidad, so that’s why we were sent there.

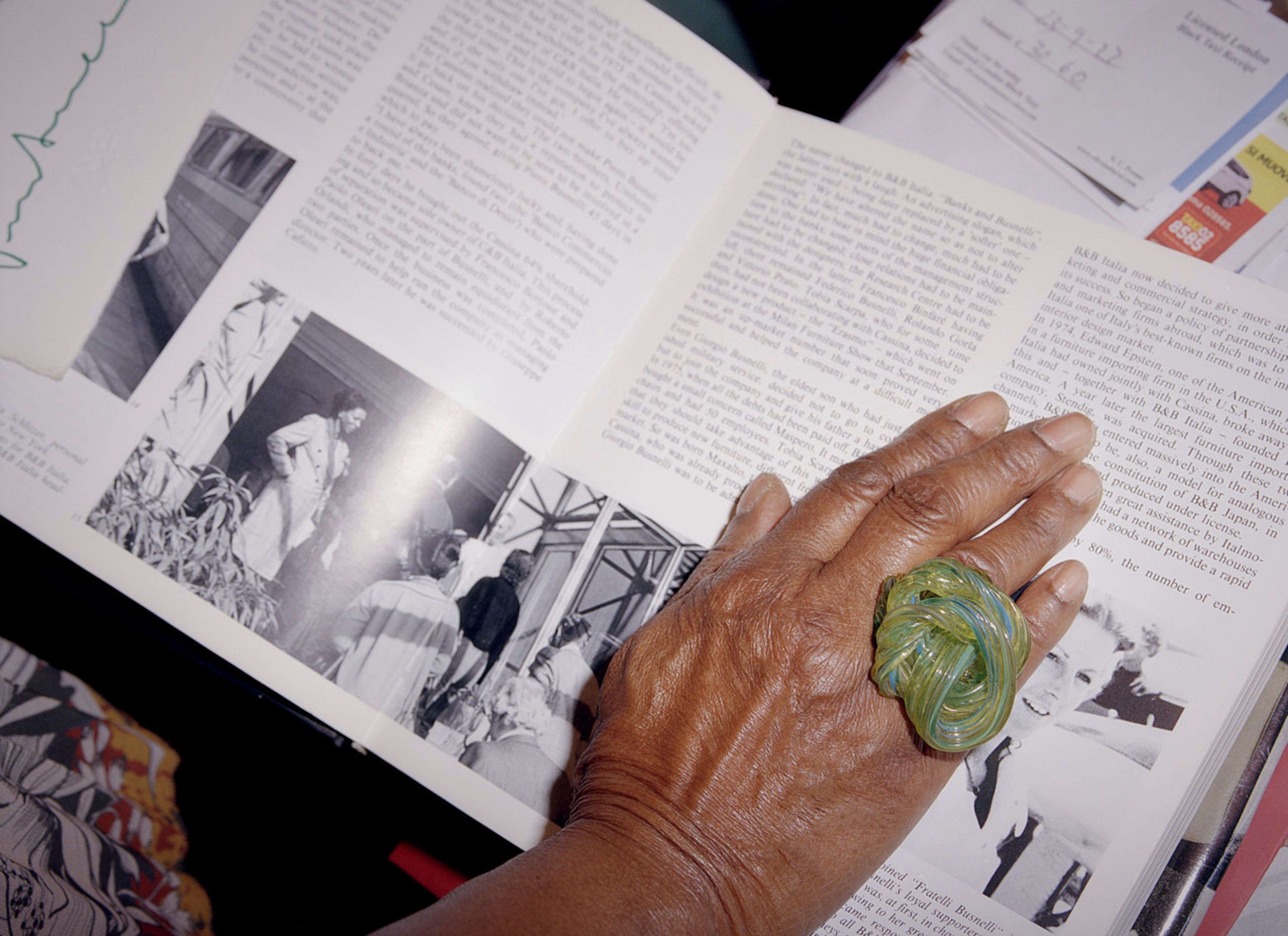

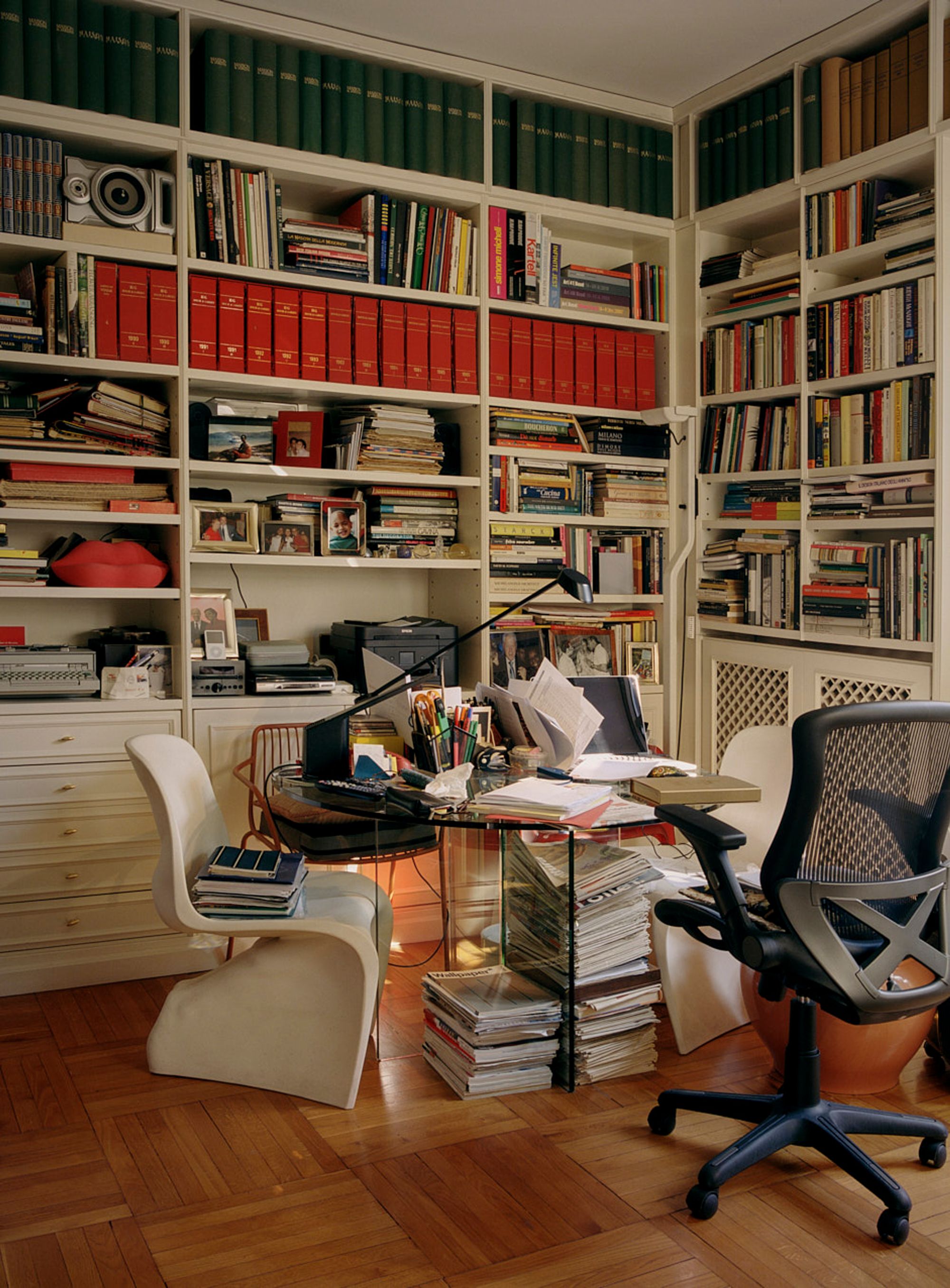

Marva Griffin in her Milan apartment. Photography by Stefan Giftthaler for El País, Spain (2022).

Were your parents originally from El Callao?

Yes. But my father’s family was from Nevis, and my maternal grandmother’s parents were from Dominica, where they mostly spoke French. My grandmother also spoke patois, a kind of French dialect.

What languages were spoken in your home growing up?

Spanish, of course. But my father was very keen for us to learn English because his family was from Nevis and he went to school in England. He’s the one who instilled in me my love for languages. That’s why after high school I went to Caracas to study languages and eventually to Perugia, to Italy’s University for Foreigners.

How many languages do you speak?

Almost five. Spanish is my first language. And then I speak English, French, Italian, and Portuguese. I’m lucky — in one day I can speak all of them with colleagues, friends, and family. With my son, who now lives in Madrid, we always speak in Spanish.

How did your parents respond to your desire to study in Italy?

Both my mother and my father insisted that all eight of us go to school, that we all go to university, and that we all independently decide what we want to do in life. I have one brother who is an engineer, another who’s a diplomat — he was Venezuela’s ambassador to Nigeria in the 70s. One of my sisters worked in the pharmaceutical industry, and the other one became a professor at university. When my mother passed away, she was very happy because all her children had found their own profession. But I didn’t make the decision to go to Italy until much later, after my first marriage. I married very young and then separated from my husband.

Marva Griffin’s Milan apartment. Photography by Stefan Giftthaler for El País, Spain (2022).

Family pictures, design objects, and lots and lots of books: Marva Griffin’s Milan apartment is a testament to the octagenarian’s eventful 50-plus years working at the heart of the Italian design and media industry. Photography by Stefan Giftthaler for El País, Spain (2022).

Why did you want to go abroad?

You must know that Latin Americans love Europe. For us it’s el viejo continente. We are young and Europe is the old continent. There’s a lot to learn, and those who can afford to go will. At school, I was always interested in historia universal, the history of the world. Most Venezuelans go to Madrid because of the language. But I was always more interested in Italy. At the time I went, everyone was going abroad to look, see, and learn, and then going back home to Venezuela. But since [Hugo] Chávez, with the economic and political situation in Venezuela, most people stay abroad. I have 17 nieces and nephews and they’re all over the world — in Chile, in New York, in Budapest, in Iceland. They all went first for studies and then stayed. It’s very sad what’s happening in Venezuela.

You’ve been awarded many honorary titles and prizes, including a gold medal from the city of Milan. When did you know that Italy was home?

I never thought about that. I love Italy. It just came naturally.

Can you talk a little bit about how you made connections and friendships when you first got to Italy?

I knew no one. I first went to Perugia, to the university for almost a year and a half, from 1968 to 1969. And then I was in Milan for half a year, to know the city and to learn, and I made some friends. Then I had to go back to Venezuela because my son Gustavo was still there. But when I got back to Caracas, I knew immediately I wasn’t going to stay. So in 1971 I returned to Milan. A dear friend helped me find a job there. I arrived in Italy on a Friday, and she invited me on Sunday for lunch. She said to me, “Marva, there are two ads in the Corriere della Sera, two jobs that are made for you.” And one was at B&B Italia, or C&B Italia as it was at the time. Incredible. So I found a school for my son, and immediately started working. Mr. Busnelli, the cofounder of C&B, was a great personality. I remember the first day at the office — he said “Miss Griffin, what are you doing this evening? I want you to meet Manlio Armellini,” one of the founders of the Salone del Mobile. He immediately gave me a lot of responsibility. My desk was across from his, and we traveled all over the world. I would translate for him and for Mr. Cassina, who was his business partner at the time. [Busnelli and Cesare Cassina founded C&B Italia in 1966. In 1973, Busnelli bought Cassina out and renamed the company B&B Italia.] They both spoke with a strong dialect from their region, Brianza, so sometimes I had to ask, “Mr. Busnelli, what did you say?” [Laughs.] I did that for three years and during that time I also built up B&B’s communications department. It was incredible because all these architects and designers were there — Bellini, Magistretti, Sapper, Zanuso, Piano — today all icons. Mr. Cassina and Mr. Busnelli would always bring me in when they were discussing new projects. No design school would have given me what I got from that three-and-a-half-year experience. Then I was approached by Condé Nast, so I said, “Mr. Busnelli, I’m leaving.” He said, “Where are you going?” You know, everyone in Brianza knows each other and they’re jealous, and Mr. Busnelli was afraid I was going to a competitor. Everybody knew me because I was the Black secretary — I was like the fly in a cup of milk. [Laughs.] But because it was a different industry, he asked me to carry on consulting for B&B Italia. I did that for 15 years. It was really, really fun.

It sounds like you found exactly what you wanted to do and where you belonged, and you gave a lot.

Yeah. I’m very grateful to the city of Milan. Everyone has been very nice to me. People are always asking about being a Black person in Milan, and I am aware that there is racism in Italy. I also see it with all this immigration of Africans into Italy. But my history is very different. And I’m sure that if I was in another, less privileged position, I would have faced more racism. But I really cannot complain. In a way I’m very happy I arrived in Milan in 1971, when it was still so Italian. For me it was interesting to learn about all this italianità. Afterwards I saw how the city grew and became more and more international — as the Salone del Mobile became international too. Salone wasn’t what is it now — today over 5,000 journalists come to the fair.

Marva Griffin founded SaloneSatellite 1998 as a space for young designers to showcase their work. In the 25 years since, over 14,000 creatives have exhibited there, many of them moving on to make lasting contributions to the world of design. Shown here is the entrance to the SalonSatellite in 2000.

You once said, “Design is a passion that needs to be nurtured in order to keep on growing.” You started at Salone in 1996, and in 1998 you established SaloneSatellite as a forum for highlighting and nurturing emerging designers. Have you noted any major changes in how design and the market have evolved?

You already gave the answer. It’s an evolution rather than a change. I believe in creativity and all these young people. They all have their own way of thinking, their own way of creating. Some are brilliant, some less. But each one has a little something. What has really changed is the technology. I’m not a digital person and I’m not on social media, but designers today have grown up with that, and the digital evolution has been very important in the way we look at design.

What’s been the most rewarding experience in your 25 years organizing SaloneSatellite?

Every year it’s different. For example, this year we decided to also invite schools. Normally we invite individual designers, who pay to contribute. It’s not much, but I think that when you have to make an effort to save money, you make more of an effort in the presentation. But for the schools we decided to give them a free space, as a thank you to all the schools and universities because they are the ones teaching all these people who are coming to us as designers. We invited 28 schools from 18 countries. Some of them are run by people who years ago participated in SaloneSatellite.

Wow.

It makes me very happy that all these people I knew right from the beginning are now doing interesting things.

Can you talk about the process of selection and how you decide which designers participate in the Satellite showcase?

Young designers apply to participate in SaloneSatellite, and I ask them to send us photos of what they have been designing. Then I invite a selection committee, which usually consists of established designers, a retailer, and someone who specializes in production. We sit for a day and review the projects. And then we select. But it’s not easy. I once asked Ingo Maurer to be part of the selection committee. We were great friends, but he always refused. He said, “No, Marva, no. I am not allowed to say that someone’s work is good or bad. You have to have them all. You want 500? Make a list, and whoever comes in first is there. When you’re over 500, give them the opportunity for next year. But you must not have people selecting their work.” Ingo Maurer. He was one of my favorites. And he’s right. It can happen that you cannot figure out from a photo if they’re good or not. It could be something that doesn’t look interesting, but then when the designer shows up in Satellite with the pieces and you see what they’re doing, you’re impressed. I always say to the jurors: “Please be good to these guys. Be generous in your judgment.”

Most of the work we do at the museum is focused on African-American history and culture. We do oral histories, and I’m collecting primarily around design and architecture. But we don’t just focus on objects, we focus on the whole story. So what about your whole story? Are you writing about your life?

I have an enormous amount of friends and writers, journalists, who want to write about me or my life. They say, “Marva, por favor, Marva please.” I always say, “Maybe when I’m finished working I’ll have the time to do it.” [Laughs.] When someone tells me I have to leave a legacy, I always ask, “A legacy of what?” I’m working. I’m doing a job.

I see it both ways. I think you firmly established the legacy with all of the mentoring through the Satellite program at Salone. What you’ve contributed already is profound. As a museum person, I always think it’s important to document. I’ve read a lot of interviews with you, but I would love to be able to refer to a book.

I already am an open book. Everyone knows about me. My close friends know, let’s say, about my love stories. And my family knows that not everything in my life has been glamorous. I’ve also had my problems, but compared to others I think I’m a very lucky person. And I’m always grateful for what I’ve received and for what I’m doing. I believe in God and I pray. I’m thankful every morning. And I’m very optimistic. I enjoy everything. I love my job, I love what I’m doing. If I don’t enjoy it, I don’t do it. I really need to please myself and to enjoy myself.

That’s good advice. Speaking to someone like me, who has been to Milan only briefly and has never attended Milan Design Week, what would you say is the secret to understanding the city?

Milan is a very, very interesting city. But you know what I call Milan? La ciudad escondida. The hidden city. Because in Milan things happen that people don’t know about — some very important meetings of top foundations worldwide are happening there. Things there that will interest you for your work. But if you really want to understand Milan, you have to get an Italian boyfriend. [Laughs.]