An eye-catching work from Juan Pablo Echeverri's 2017 series Identidad Payasa. Courtesy the estate of Juan Pablo Echeverri.

A room inside Mansión Echeverri prominently featuring Juan Pablo's 1999 work zooMetidas, a series of photographs with pink backgrounds in turquoise frames. Courtesy the estate of Juan Pablo Echeverri.

Last September, while visiting Bogotá for the 20th anniversary of ARTBO (one of Latin America’s biggest contemporary art fairs), I found myself on the top floor of the Ágora Bogotá Convention Center, a monumental lightbox situated in the Quinta Paredes neighborhood, where I was drawn into the exhibit of Berlin-based Klemm’s gallery by an odd, life-size oval-shaped diptych, a double portrait of two fantastical cat people: equal parts cute and frightening. The seemingly identical subjects were done up in white face paint with blue snouts and a mop of shaggy hair. Each wore a dress shirt, sparkling, baby blue vests, and matching bow ties.

The eye-catching piece was from the multimedia Colombian artist and musician Juan Pablo Echeverri’s series Identidad Payasa (2017), a collaborative project in which Echeverri befriended Mexico City street clowns and invited them back to his studio, photographed them, and then asked each clown if he could wear their costume, for a self-portrait of himself dressed as them. It’s a striking example of Echeverri’s relentless exploration of identity through the many lenses of global pop culture; the petite, wildly exuberant man tragically died of malaria two years ago at the prime age of 43, remembered among his peers for his vibrant obsessions, twisted worldplay, boundless curiosity, and his generative self-portraiture practice.

An eye-catching work from Juan Pablo Echeverri's 2017 series Identidad Payasa. Courtesy the estate of Juan Pablo Echeverri.

For Identidad Pasaya, his 2017 photo series, Colombian multimedia artist Juan Pablo Echeverri photographed himself in the outfits of clowns he met on the streets of Mexico City. Courtesy the estate of Juan Pablo Echeverri.

While he was alive, his body of work went largely unrewarded by the commercial art world. Although this was sometimes frustrating to him, he never let it slow his output, making new work every day for over 20 years straight. Unfortunately, it was only after his sudden death that a much-needed correction to the art historical record began. Friends and family, including his Fragile bandmate, artist Wolfgang Tillmans, who exclusively provided a special portfolio of images for this story, and Juan Pablo’s sister, historian Marcela Echeverri, rallied around his work to ensure it was more widely viewed. In 2023, Tillmans hosted the show Identidad Perdida at his space, Between Bridges, in Berlin, a commemoration of Echeverri’s life and work selected from over 30 unique series of his photographic and video works. Simultaneously, in New York, James Fuentes Gallery hosted a show by the same name in conjunction with the publication of the monograph simply titled Juan Pablo Echeverri by the gallery’s press. “Juan Pablo was a genius for his extreme dedication to portraiture, creating and documenting every possible avatar of himself,” Fuentes says. “For someone who died too young, he left an incredible amount of work — an incredible legacy,” he reflects with a smirk, clearly still amused by Juan Pablo’s singular approach to art and life.

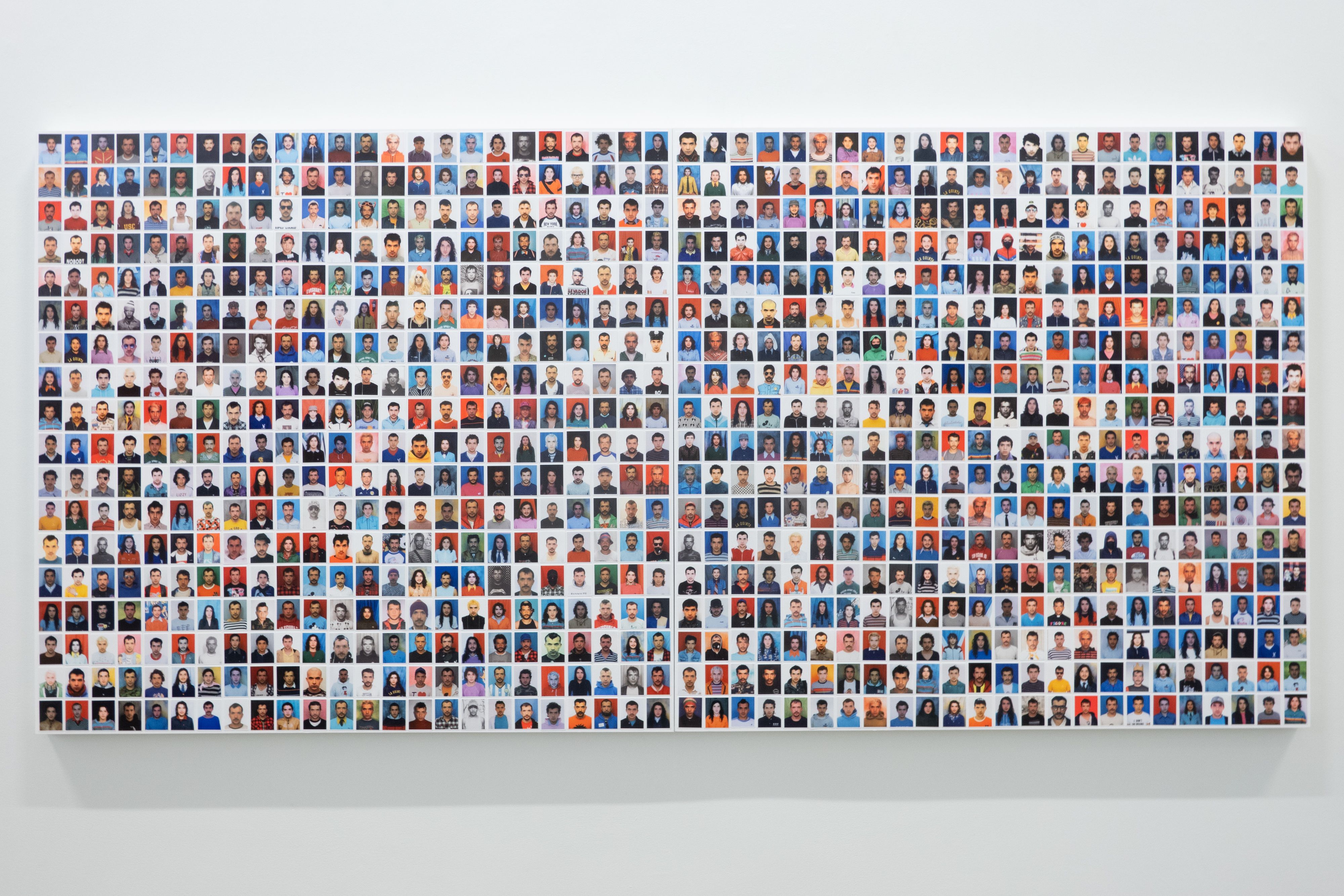

In the monograph’s foreword, Tillmans described his friend as someone who “wanted to trace life, tracking contemporary ways of living across cultures in the modes of du jour — a man with great unfiltered empathy.” The double exhibition resulted in many successes. New audiences discovered his work, and the press celebrated it — Aperture published Tillmans’s foreward, and thoughtful profiles in Artnet and The Guardian followed. MoMA acquired a diptych by Echeverri — miss fotojapón #4 and miss fotojapón #5 (1998–2022) — for their permanent collection. The work is comprised of two collages, each featuring 432 inkjet prints for a total 864 versions of Echeverri’s daily style evolution.

A view inside Mansión Echeverri. Marcela Echeverri, Juan Pablo's sister, and Federico Martelli, a close friend, are working towards preserving Juan Pablo's legacy, and have secured a grant to keep the Echeverri Mansion open in its current form until July 2025. Courtesy the estate of Juan Pablo Echeverri.

The works miss fotojapón #4 and miss fotojapón #5 (1998–2022) on display at the show Identidad Perdida at James Fuentes Gallery in New York, featuring a total of 864 versions of Echeverri's self portraits. Courtesy the estate of Juan Pablo Echeverri.

Echeverri’s home is as much a testament to his exuberant exploration of identity as his artistic practice, which I learned at ARTBO from Klemm’s co-founder, Silvia Bonsiepe. As she excitedly showed me Identidad Payasa, her eyes lit up further when she explained that they had collaborated with ARTBO to make the artist’s home available to the art fair’s attendees as an off-site exhibition. “His house is mind-blowing. It’s the most personal, intimate, and comprehensive insight into an artist’s mind that I’ve ever seen,” Bonsiepe readily offered. “It is a cosmos of thought that never stops. When you enter the house, you enter Juan Pablo’s mind.”

An outside look at Mansión Echeverri, the “Transylvanian-style” house in the La Magdalena neighborhood of Bogotá that Juan Pablo Echeverri lived in from 2017 until his death in 2022. Courtesy the estate of Juan Pablo Echeverri.

Inside Juan Pablo Echeverri’s home. Courtesy the estate of Juan Pablo Echeverri.

The Echeverri Mansion, as Juan Pablo called it, is located on the second floor of a curved, Modernist building that he described as “Transylvanian-style” in the La Magdalena neighborhood of Bogotá. The artist lived here from 2017 until he passed in 2022, and he used the Mansion as much as his living quarters as he did as a showroom, study, and storage space. As I awaited our tour in the building’s outdoor courtyard, I chatted with a handsome forty-something Colombian man who had grown up with Juan Pablo and was still clearly mourning the loss of his friend. The stranger, who preferred to go unnamed, explained, “Juan Pablo was a role model for my generation. He was the first openly queer person in Bogotá. Every day, he fearlessly dressed in over-the-top outfits. That was no small feat in the ’90s in this very Catholic country. Most of the city knew who he was.”

Juan Pablo Echeverri’s home. Photographed by Wolfgang Tillmans.

Juan Pablo Echeverri. Photographed by Wolfgang Tillmans.

The stairway leading to Juan Pablo Echeverri’s home. Photographed by Wolfgang Tillmans.

Juan Pablo Echeverri’s home. Photographed by Wolfgang Tillmans.

Juan Pablo Echeverri in his home. Photographed by Wolfgang Tillmans.

Juan Pablo Echeverri’s home. Photographed by Wolfgang Tillmans.

Juan Pablo Echeverri and friends hanging out in his home. Photographed by Wolfgang Tillmans.

Once inside the building and up a grand curved hallway staircase, we are greeted by his sister, Marcela, who looks so much like her brother that she could have almost been mistaken for his ghost. Upon entering his maximalist living room, it becomes clear why his supporters invested in preserving the apartment. The home itself is a total work of art, Juan Pablo’s biggest and most ambitious installation. Each room has a theme, with collections of memorabilia to match it. The walls are covered in references to his creative heroes, from Almodóvar to Warhol, while art, posters, and collectibles from other artists hang alongside Echeverri’s own, his inspirations and his own creative output coming together in one infinite loop. “It’s kind of like eating something and throwing it up. This has been inside me and now I give it back to the world,” Juan Pablo once said of his relationship with pop culture and art-making. Even with only a few people inside the interior, each space in his home starts to feel like a vibrant party.

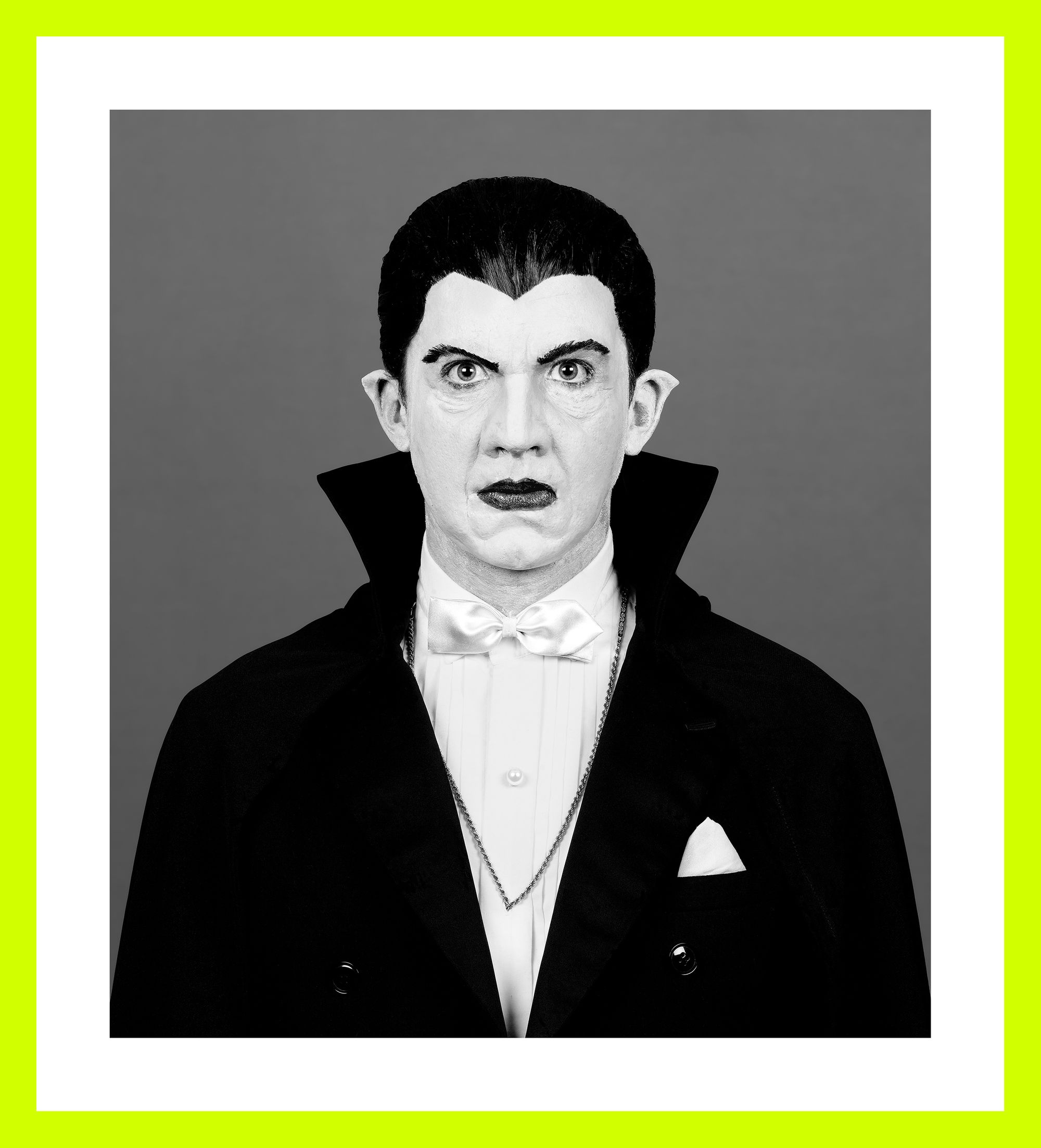

DRÁCULA, Famoustros, 2012. Courtesy the estate of Juan Pablo Echeverri.

FRANKENSTEIN, Famoustros, 2012. Courtesy the estate of Juan Pablo Echeverri.

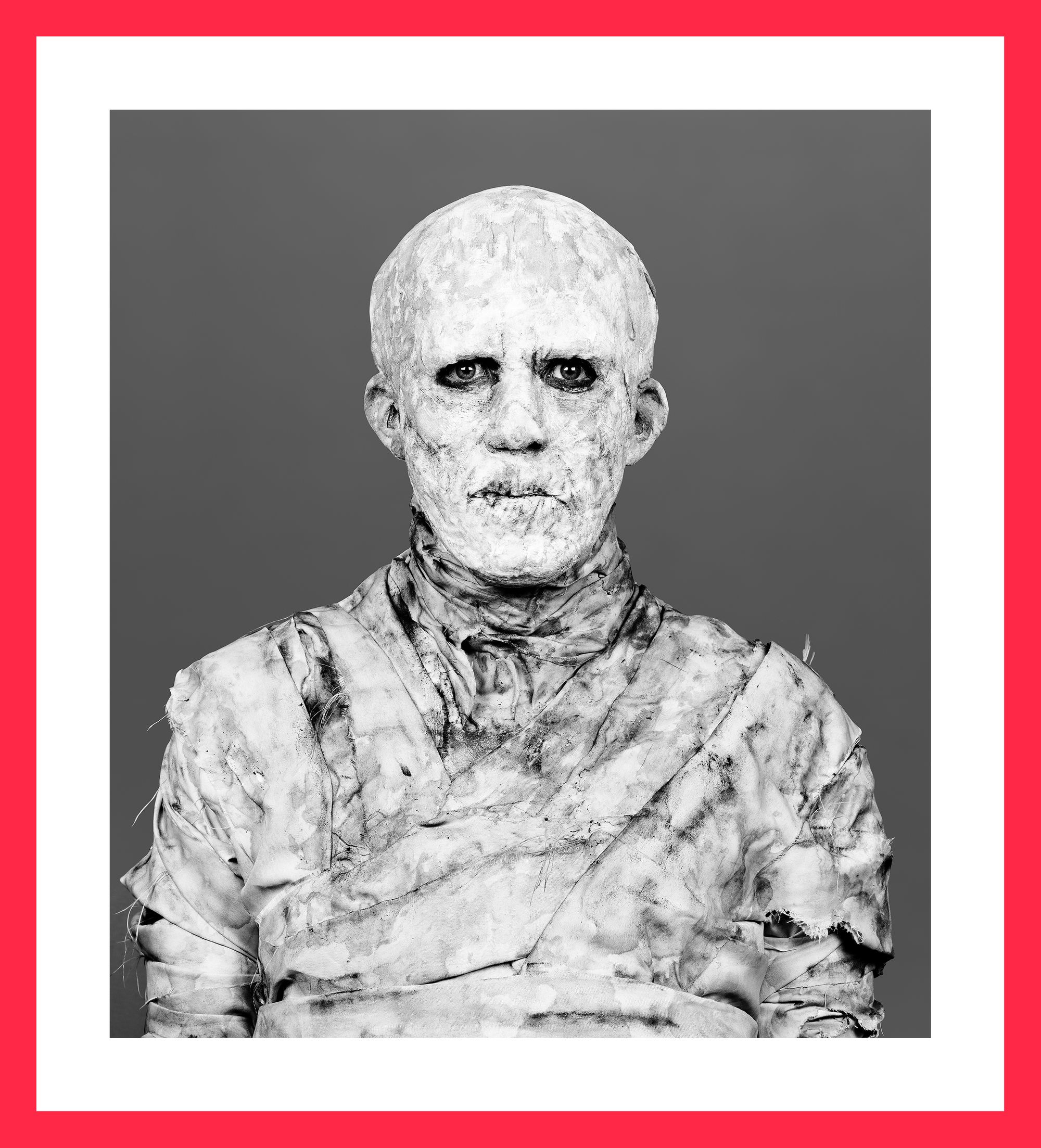

MOMIA, Famoustros, 2012. Courtesy the estate of Juan Pablo Echeverri.

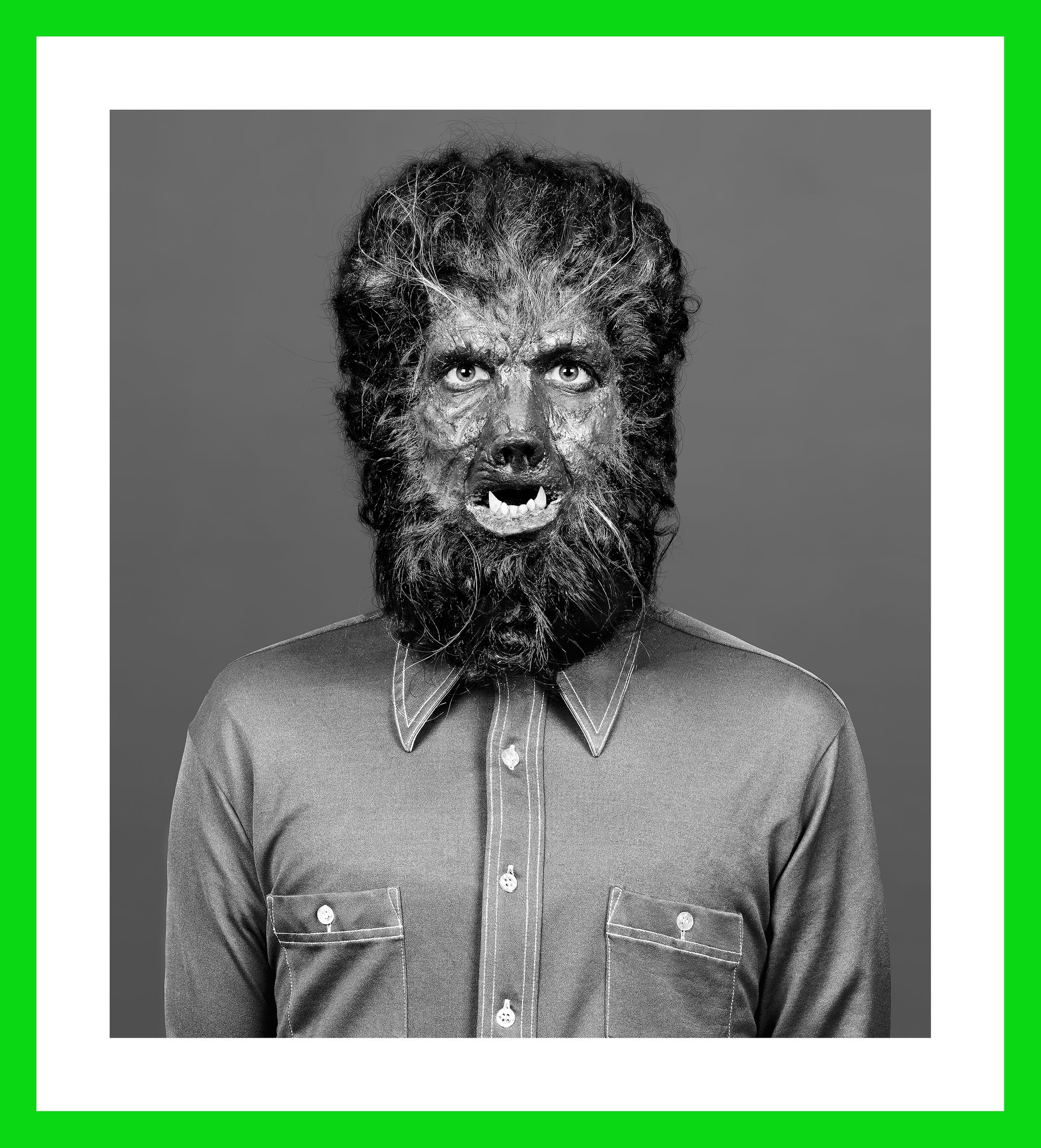

LOBO, Famoustros, 2012. Courtesy the estate of Juan Pablo Echeverri.

The living room’s foreshadowing theme is death, anchored by a bold red and white striped floor and a wall covered in posters from different countries for the ’70s horror film The Eyes of Laura Mars. The mostly black poster features a high-gothic version of the face of Faye Dunaway, her two white eyes piercing through the darkness. All of the posters are positioned to stare across the room, forever fixed on a large portrait of Juan Pablo, playing dead with both eyes closed, dressed formally as if he was prepared for an open coffin. Just as in the film, Laura is viewing a death that becomes art.

In the living room of Mansión Echeverri, Juan Pablo covered a wall with movie posters of the 70s horror film The Eyes of Laura Mars from many different countries. Courtesy the estate of Juan Pablo Echeverri.

La muerte me sienta bien, 2016. Courtesy the estate of Juan Pablo Echeverri.

As we tour each room, with collections of commercial ephemera overflowing, I start to feel supercharged with the energy of pop culture’s most prized achievements, which is how I imagine Juan Pablo must have felt every day. Equal to that energy is the artist’s overwhelming presence; almost everywhere you look, some version of Juan Pablo is looking back at you: the artist as a werewolf, a drag queen, an elderly gay man, a truck driver, an emoji, a tennis champion, or a priest. Echeverri fixated on stereotypes and icons, collecting, enjoying, and repeatedly transforming himself into his own versions of them. As William Van Meter, editorial director of Artnet, astutely observed in his profile of Juan Pablo, “In many ways Echeverri’s art became the act of releasing vast editions of himself to collect.” In the music room that doubles as his closet, our tour guide, his neighbor Federico Ruiz, jokes, “There is definitely pressure to choose a fabulous outfit when Prince is watching you get ready for the day.”

A peek at the pop culture and art-covered inside of Mansión Echeverri. Courtesy the estate of Juan Pablo Echeverri.

Juan Pablo Echeverri’s personal passport photo booth, Foto Japón. Courtesy the estate of Juan Pablo Echeverri.

What seems to be his study is wallpapered in tiny self-portraits. In this room, his sister lists her brother’s early influences: “As a student, Cindy Sherman, Nan Goldin, and Duane Michals were outsized influences on his developing practice.” It’s clear that these artists gave him the confidence to mine his own life, pushing their concepts of identity, character, self-portraiture, and autobiographical image-making into a wild, flamboyantly queer space. He added all the tackiness and bravado of consumer culture, along with his own penchant for performance, drama, obsession, and endurance.

In 2000, long before the selfie came into dominance, he began the project miss fotojapón, in which he committed to taking one passport photo of himself per day — a practice that became an obsession lasting twenty-two years. Reprinted in his monograph, is a 2012 interview with his friend, artist Russell Martin, in which he described being so deep into his practice that his motivations became abstract: “I got to the point where it was a vicious cycle, and I didn’t really know if I was changing for the pictures or taking pictures for the changes.” This room includes one of his prized possessions: a photo booth, a gift from the owner of Foto Japón, a chain of photographic stores after which the project is named. This enormous present was given to Juan Pablo after seventeen years of taking his pictures at their store.

Together, Federico Martelli, one of Echeverri’s closest friends and Marcela Echeverri are working towards creating a foundation to promote Juan Pablo’s legacy. They’ve received a grant to preserve the Echeverri Mansion until July 2025. For those unable to visit Bogotá during this time frame, a virtual tour of the apartment is available, where Juan Pablo’s dynamic world, passport photos, Mickey Mouse figurines, and all, can be enjoyed from afar. Visiting an artist’s home often provides a sharp, intuitive insight into their worldview. In their home, you can get an idea of how the artist lived their art. In the Echeverri Mansion, you come close to grasping the essence of a man who transformed the rejection he faced (from his Catholic country and the art world) into a powerful force for creation. An artist that channeled his discontent energy into world building, every inch of his queer, punk, refuge demonstrates an almost religious belief in the power of image and style as tools for self-discovery, evolution, and reinvention. A vibrant hub of communal creative energy during his life is now a farewell exhibition in his death.

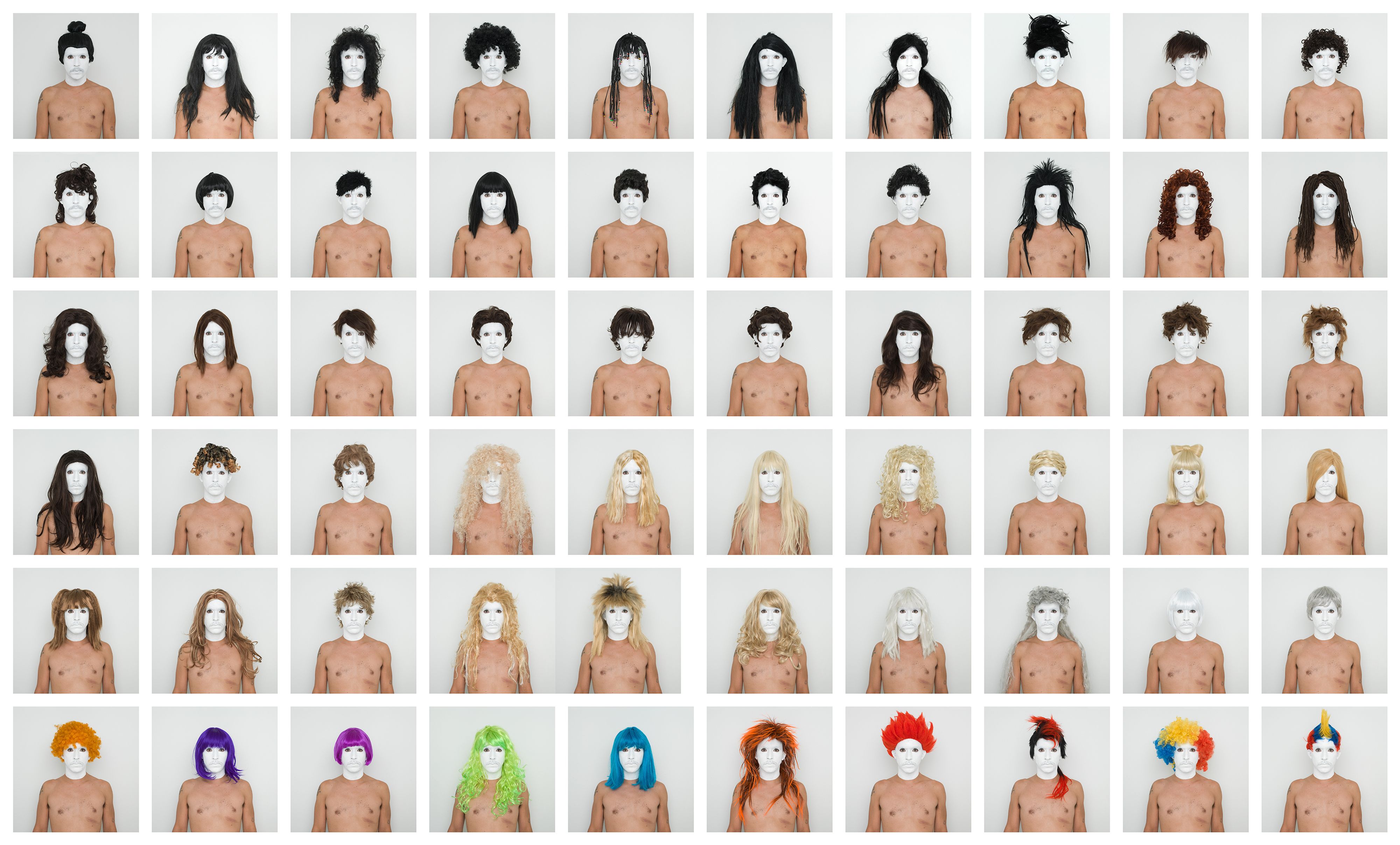

Peloquitas, 2013. Courtesy the estate of Juan Pablo Echeverri.

futuroSEXtraños, 2016. Courtesy the estate of Juan Pablo Echeverri.