CABARETS, CURRENCIES, AND THE ARCHITECTURE OF DISCOMFORT

Irena Haiduk Talks Through Nula at Shanghai’s Rockbund Art Museum

by Whitney Mallett

Irena Haiduk. Photo by David Born.

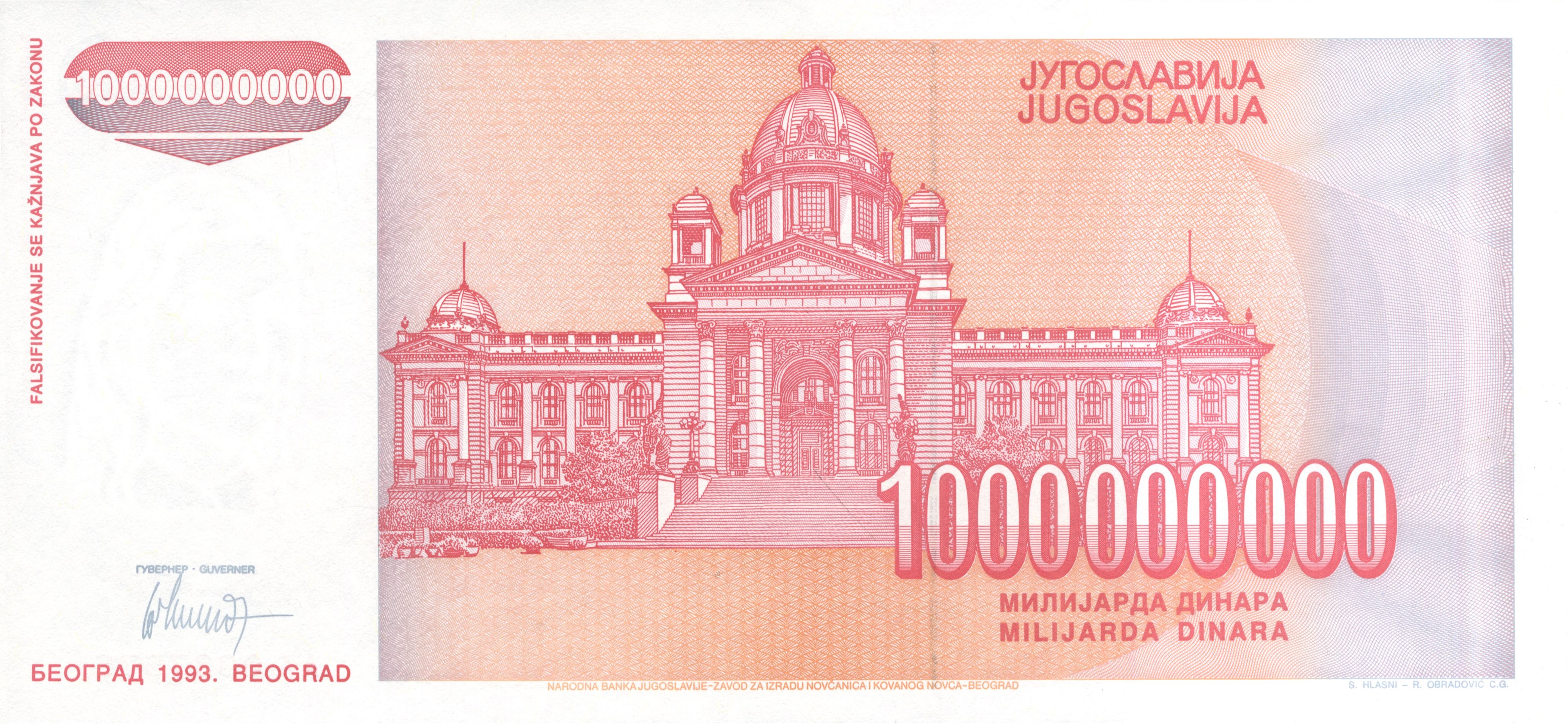

When you step into Irena Haiduk’s exhibition Nula at Shanghai’s Rockbund Art Museum (RAM), a story unfolds spatially. Imagine an Escape Room art-directed by David Lynch, an underground cabaret amid the chaos and hyperinflation of war. From the outset, the exhibition absorbs visitor entry processing into its narrative: cloaked museum staff greet you, pulling you into a fantasy world inspired by the war-torn former Yugoslavia Haiduk grew up in. You’re handed a wad of cash — bills printed with so many zeros they echo the billion-dinar banknotes circulating in mid-1990s Yugoslavia. With these you can attend different events and talks throughout the course of the exhibition’s run until February 2026. At check-in, you’re invited to fill out a form choosing a character to inhabit during your visit. The list presents a constellation of interconnected figures, each modeling a different strategy for survival and desire in a society under collapse.

The exhibition draws its source material from a novel of the same name that Haiduk co-wrote with writer and visual artist Blakey Bessire. Set to be published this fall, its logline reads: “As the curse of war disfigures all, a family of three women — a bank illustrator, a statistician, and a teenager — transform into a forger, a prostitute, and bait.” The story is abstracted from Haiduk’s personal experiences as a teenager, when a cabaret became a lifeline for her and her family. Adolescent Haiduk worked as a prop assistant, while her mother performed in the theater’s after-hours burlesque show — a form of wartime survival sex work. Haiduk has previously reimagined this formative venue, most notably in her otherworldly Cabaret Économique performance at Hamburger Bahnhof, Swiss Institute, and Anita Berber. For Nula, the stage is transposed into the RAM installation, and a larger world built around it, including the cabaret MC’s office and a smuggling tunnel. Moving through the rhizomatic rooms there’s a stylized worldbuilding drawing from typologies as different as nightclub, haunted house, carnival hall of mirrors, and concept retail store. Their interconnectedness is intentionally fractured. Backstage, for example, exists on a different floor from the main stage, heightening a sense of dislocation within the immersion.

Nula is not only an exhibition but also a site of production over its ten-month run. A narrative feature is being filmed inside the installation during this time, adapting the novel’s story with cinematography by Manuel Alberto Claro, the lens-based virtuoso behind Lars Von Trier’s Melancholia and Nymphomaniac. RAM has been deeply collaborative in the process, even assisting with casting local actors and performers. Haiduk credits her 13-year relationship with the museum’s director and chief curator, X Zhu-Nowell, as foundational to the concept: “X was always interested in the writing I was doing to ground my practice, the ‘Against Biography’ text and the incorporation documents for Yugoexport,” Haiduk explains, referencing her earlier conceptual project for documenta 14 in 2017, which also probed bureaucracy and alternative economies. When Zhu-Nowell invited the Belgrade-born artist to imagine what they could realize together at RAM, Haiduk was adamant that she wasn’t interested in the exhibition format alone anymore; she really wanted to make this film. Focused on socially-engaged, research-driven practices and new commissions and experimental forms, RAM — an independent, privately-funded institution in Shanghai’s historic Bund district, celebrating its 15th anniversary this year — has proven itself a rare partner capable of bringing Haiduk’s unconventional vision to life. Housed in a 1932 Art Deco building originally designed for the Royal Asiatic Society, RAM is part of a cluster of buildings David Chipperfield Architects updated in the early 2000s in this district that was briefly a hub for foreign banks before a century of openness ended in 1943. Today, the neighborhood has reemerged as an international cultural locale, increasingly populated by blue-chip galleries such as Almine Rech, Perrotin, and Lisson — an apt setting for Haiduk’s investigation of desire and exchange.

Installation view, Irena Haiduk, Nula, Rockbund Art Museum, Shanghai, May 2, 2025–Feb. 8, 2026. © Rockbund Art Museum, Shanghai. Photo: Yan Tao.

Whitney Mallett: The theatricality of your show fits in so well into Shanghai’s historic Bund district where even the doormen have these period-costume uniforms and cosplayers use the Art Deco buildings as backdrops for their photos. The cloak that the museum staff wear as part of your exhibition-experience is not that different from those anime-character costumes. How did you approach this context of the neighborhood and the museum’s architecture?

Irena Haiduk: There were so many times when I felt, “I’m flowing in the river of fate.” Four years ago, when I found out he’d passed away from COVID-19, I took a button given to me by [the cabaret MC] Lane [Gutović], broke it up, and placed it in pearl oysters. Those pearls were already maturing when I made the site visit here and found out Shanghai is a huge place for pearl production. This area was a banking hub, so it just clicked, because the work is really about economies. The highly performative culture around the museum made me think that it would be natural for people who are entering the museum to enter the building and become these characters. I love the in-between-the-wars Art Deco minimal Modernism peeking through the museum’s architecture. The curved edges. It’s a place that could have been built in the 1950s or 60s, or in the 20s or 30s. There’s something very timeless about this form. I really love the difference in ceiling heights on every floor. There’s something charming about that, and also demanding and non-standardized. What the Renaissance people used to call Vitruvian: in relationship to a body. I wanted to make the space strange, like a collaging of interiors. I had this Kafkaesque idea from The Trial. There’s this disorienting rhizomatic form in that book. You’ll have a person in an office, and then under the table there’s a small door, and you pass through the door, and there’s a painter’s studio, and you pass through another door, and there’s a room where someone is being whipped, and the next room is a cathedral. I really like these unexpected cuts that also make the experience of a person moving through space disorienting and surreal. Creating these emotional spaces, each room is differently colored. When you come in, it’s very bright, very retail. Then the MC’s office is quite moody and red, like the bathroom from The Shining. The smuggling tunnel is, again, quite bright and infinite. Lots of set techniques have been installed into this physical theater of the body moving through space. Each space feels different.

You’ve suggested an important part of your practice is a belief that we can’t be told what to do; we have to be seduced into doing something. The many-angled silver room, with a mirrored floor and undulating ceiling lights, in particular, is very seductive.

If our ambition is to create new desires that are unlike the ones we have had before, then we need to also be very generous with formulating an aesthetic that is different. Differences even within the exhibition are important for me. My biggest ambition is to be so generous that when people enter a space, it is acting on them as much as they’re acting on it. I think that silver room is probably the most effective, because it’s meant to disorient but also make one want to go into every nook. I really like non-orientable spaces. For example, I was sitting there this morning, and I saw this guy who kept coming in and going out because he didn’t know how to go to the other side. And then he just sat down. I think the general idea of the labyrinth, and a person being willing to follow the red thread, is key. I was a topologist, so this idea of orientability as a dimension comes up.

One-billion-dinar banknote printed in the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, 1993. Image courtesy of Irena Haiduk.

I don’t know what topology is. Was this your specialty when you studied mathematics?

Yes, algebraic topology. Oh, my God, it’s awesome. So in topology, a donut is the same as a cup, for example, because it has one hole and no edge. Topology is a way to probe into classing objects. When you get into fourth- and fifth-dimensional objects, you can’t see them. You can only describe them by affecting them with things. And these are called dimensions. If you puncture the object, that’s a dimension. Another dimension is being able to orient something, or not. Non-orientability is important because it really allows the person walking through the space to get to know it without having a predisposed set of rules. It’s like experimental cinema; you see a film that’s six hours long, and for the first 30 minutes, you’re bored to death. But after that, your attention span changes, and you’re able to sit with it. You give in. Good experimental space allows you to learn how to be in it through a process of being in it. I think you have to be generous to make people want to do that. I really believe in demonstration. It’s so important to demonstrate to people that something is possible. In whatever sphere of life, if they can experience it, they’re more likely to want to do it themselves, than if you’re just telling them what to do. People are highly intelligent bodies, and when they’re in a space that makes them move in a different way, they will sense it, literally. They will feel what’s going on.

Installation view, Irena Haiduk, Nula, Rockbund Art Museum, Shanghai, May 2, 2025–Feb. 8, 2026. © Rockbund Art Museum, Shanghai. Photo: Yan Tao.

Can you expand on this term you’ve used before — the “fiber optic image”?

I like to separate images into fiber optic to mean this thin, infinitely distributable image, which is very quick and appears to show something that is real. This is the image that I have a problem with and the way it circulates — the speed at which it circulates, how it circulates, and what material it carries. I’m not against images. I’m into image ecology. We need to slow down our image consumption a little bit and be aware that we’re able to perceive more than we’re conscious of. Images do a lot of work in who we are and what we will become, which is why it’s important to be open to them, but also to be very aware of what they do to us. It took us 500 years to understand what the medium of the book does to us; it took us forever to understand what speech — and everything that is not fully embodied within the brain itself — does to us. With all these images on our cell phones, we don’t know what it means to be touching glass all day, not any other texture. This is the primary sensory intake that we have. This smoothness of the world.

The point is not to be critical of images. The point is, how do we make an image that makes us want to live? And how do we make a narrative that connects to people? This mediated life through the optical world is like the enlightenment-based justice system which captures us at birth. The Enlightenment really developed this idea of capturing bodies and the idea of the state being that you surrender your body for rights. That your body then can be imprisoned or captured if you don’t follow the rules. Roman law is based on always owing in flesh. You’re in this condition by birth. You were never asked to participate. Locke’s social contract theory and theories by Hobbes and Rousseau all start from the axiom: you always owe in flesh, and you are always born a debtor. I think the most radical thing that you can do with art is: one, to allow people to understand that they’re captured, and two, to allow them a means to get their bodies back.

Having a spatial, embodied experience is part of that?

It’s very important to understand that we live in space because of what our devices are doing is this optical-image death drive. All the media is flattened, but there’s more capability to render things in higher and higher resolution. On one hand, we’re in an ecological disaster, and then there’s this world of images, which is so haptic and high-resolution; we’re substituting our world. We have a beautiful image of a beach that will no longer be able to exist, but you can embody it in a video game. We’ve been preparing ourselves to get rid of our bodies. So in a way, living in all senses and in three-dimensional spaces is radical all of a sudden.

How did you design the installation to work against this? You mentioned M.C. Escher as a reference.

Collaging is amazing because it makes your eye make the image; there are things that don’t fit together, and then your eye actively has to compose the image for yourself. Escher has this great way of making you go deep. He has depth and shallowness at the same time With [Giovanni Battista] Piranesi, also, there’s this amazing inability to discern what is up and what is down; what is texture and what is a real thing. Gaetano Pesce’s foam work is also a reference because it has something so organic about it. Having been through bombing and explosions, I became slightly obsessed with the shape of smoke. When a building collapses from a bombing, it creates a very ink-in-the-water feeling of the shapes. I love the way Pesce uses foam to create that shape, but somehow it also looks like a sea rock. So this idea of water is also very important in this space. We projected an almost water-like reflection on the ceiling. The surprise upon coming into the room is meant to create this feeling that you don’t know what’s going to happen.

Installation view, Irena Haiduk, Nula, Rockbund Art Museum, Shanghai, May 2, 2025–Feb. 8, 2026. © Rockbund Art Museum, Shanghai. Photo: Yan Tao.

Was there a moment when you really felt the violence of abstraction?

Before the war, Yugoslavia had been very open to the West. People were watching TV shows like 90210. I remember them cutting the pipe when I’d just gotten into the X Files. Episode nine. I was 11. It was very strange for me. We didn’t see any TV from the West after that. We saw it again for the first time in 1999 with the footage of CNN showing Yugoslavia being bombed. I remember when the Avala Tower fell. I was with my friends, and we were so close to it that there was no time to run. We were engulfed by radioactive smoke for two hours before they dragged us out. You can’t outrun these clouds when the buildings fall. The reality of an exploding or crushed body was such a violence for me to see. But even experiencing the bombings every day, sometimes twice a day, didn’t affect me as much as seeing the CNN footage and knowing no one cared about what happened to us. We thought we were human, but we were not. We were just clouds.

Way later, I read [Walter] Benjamin for the first time. He wrote about one of the most characteristic forms of fascism as abstracting violence and using aesthetics to do it. Reading that, I remembered that moment when I saw us as these night-vision clouds and the entirety of this violence being completely abstracted. The only thing that could heal me was experimental metal music. I think that bombing, generally, is so violent because you’re absorbing the destruction of your home through its vibrations. This is why it’s so traumatic for populations all around the world. What’s happening in Palestine, in Ukraine, and anywhere that there’s war is that they’re usually using cluster bombs and radioactive, or at least semi-radioactive, bombs with a very long half-life, which no one talks about. Not only are they destroying your home, your loved ones, and the architecture of their lives, but also your body accumulates radiation and absorbs these sounds. That’s something I was really aware of. You can close your eyes, plug your nose, cover your skin, but you can’t shut out vibration. It enters your body no matter what.

How does the myth of Medusa relate to your understanding of image ecology?

Every culture has a character that’s a mermaid or a gorgon. There’s something so archaic about this idea that we want to dispose of ourselves. There is language for it in our oldest myths. I thought of Medusa’s head as the first camera. Pessos comes into Medusa’s cave with a shield, reflects her own image back at her, and she is startled by how horrible she is. He severs her head, and keeps it to kill the people that wronged him. For me that’s the first perfect depiction of this camera that annihilates. And for us to think that we can wield it? For us to think that we know the difference between what is alive and what is dead in an image? This thinking is very sick. There are so many channels of the image that we do not understand. It’s the same eye that thinks it can, by the act of looking or the act of speech, transform something from a living thing into a dead thing and back. When you look at a Dutch Golden Age still life, you’re looking at this beautiful arrangement, but you’re also looking at extreme violence committed through colonial trade. The lemon is dead. The butterfly is alive. Or, think about Wanderer above the Sea of Fog by Caspar David Friedrich. The Rückenfigur makes you join the viewer in the painting. There’s no choice. You’re behind him, so you’re following him. He’s looking at this ambiguous landscape which is infinitely available to him. What will he conquer next? It induces this wanderlust that the Germans have invented, which is love for the far away, which is very close to colonial imagination and the explorer’s mindset. The mind that thinks everything’s available and everything can be mapped is the mind that thinks they know what’s human and what’s a thing, and can turn a human being into a thing.

The idea of differentiating, or not, between a human and a thing makes me think of the uncanny, which feels important to your exhibition. The root of this word comes from unheimlich, which means home. You’ve said before that your art is your home.

What the theater and art were for me when I was younger, I have to be that person for other people now, and I’m capable of this. Making this show was one of the ways to be responsible. I don’t belong anywhere except in my art. What I learned from the theater was how much love and fun there is in being together and making things together. So art is not just my home. I want to welcome people into it and for it to be a home for them. I want to get away from the idea that an uncanny feeling is negative or scary. I want people to be comfortable with the agency of everything around them, and also to be okay with being uncomfortable. The second-floor space in this exhibition is not a comfortable space, but if you are okay with learning how to be uncomfortable in a space, you can enjoy being anywhere after a while.

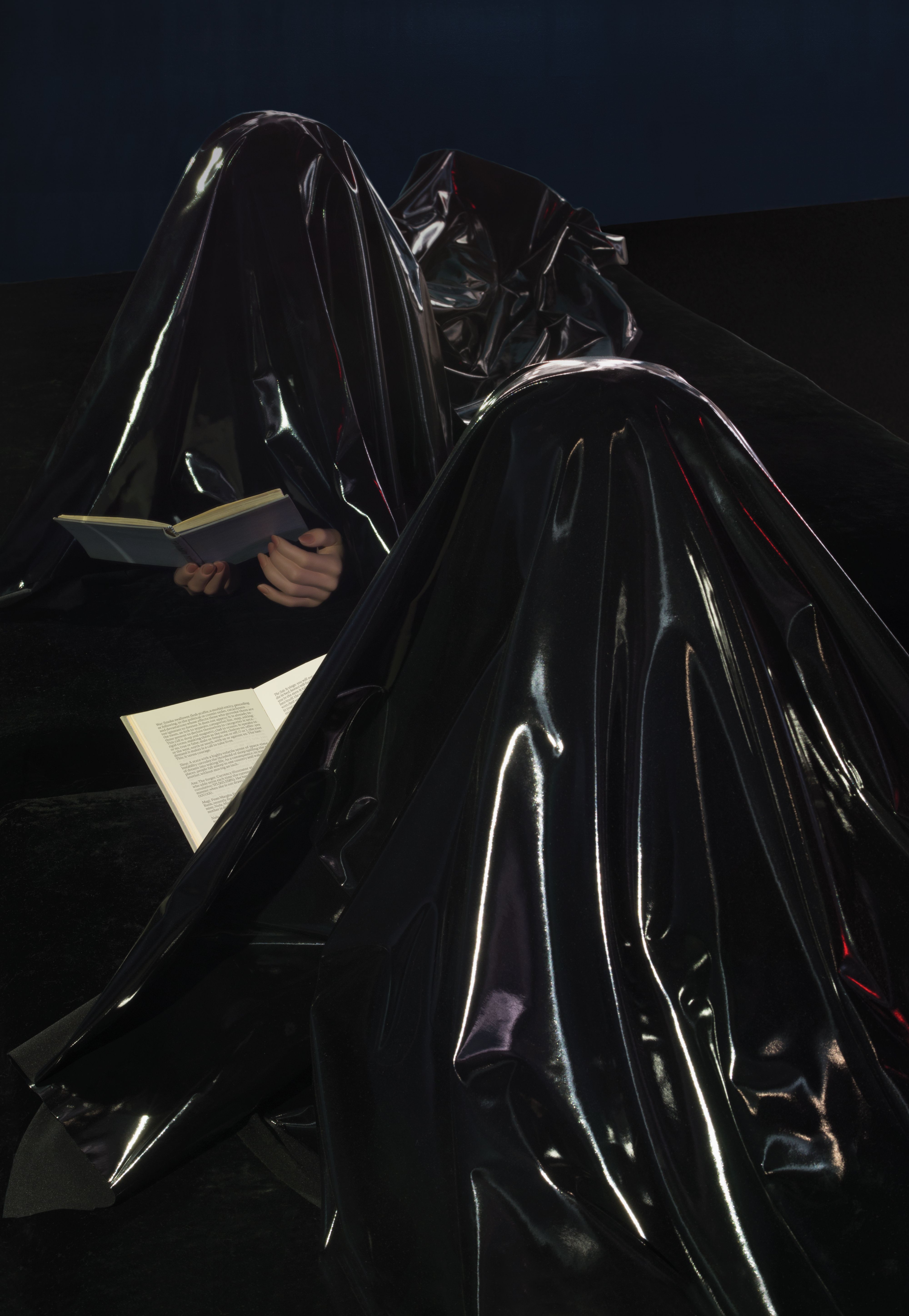

Irene Haduik, NULA, 2024, feature film vertical ad for digital formats. Produced by Yugoexport and the Swiss Institute. © Irena Haiduk. Image courtesy of Irena Haiduk. Photo: Anna Shteynshleyger.