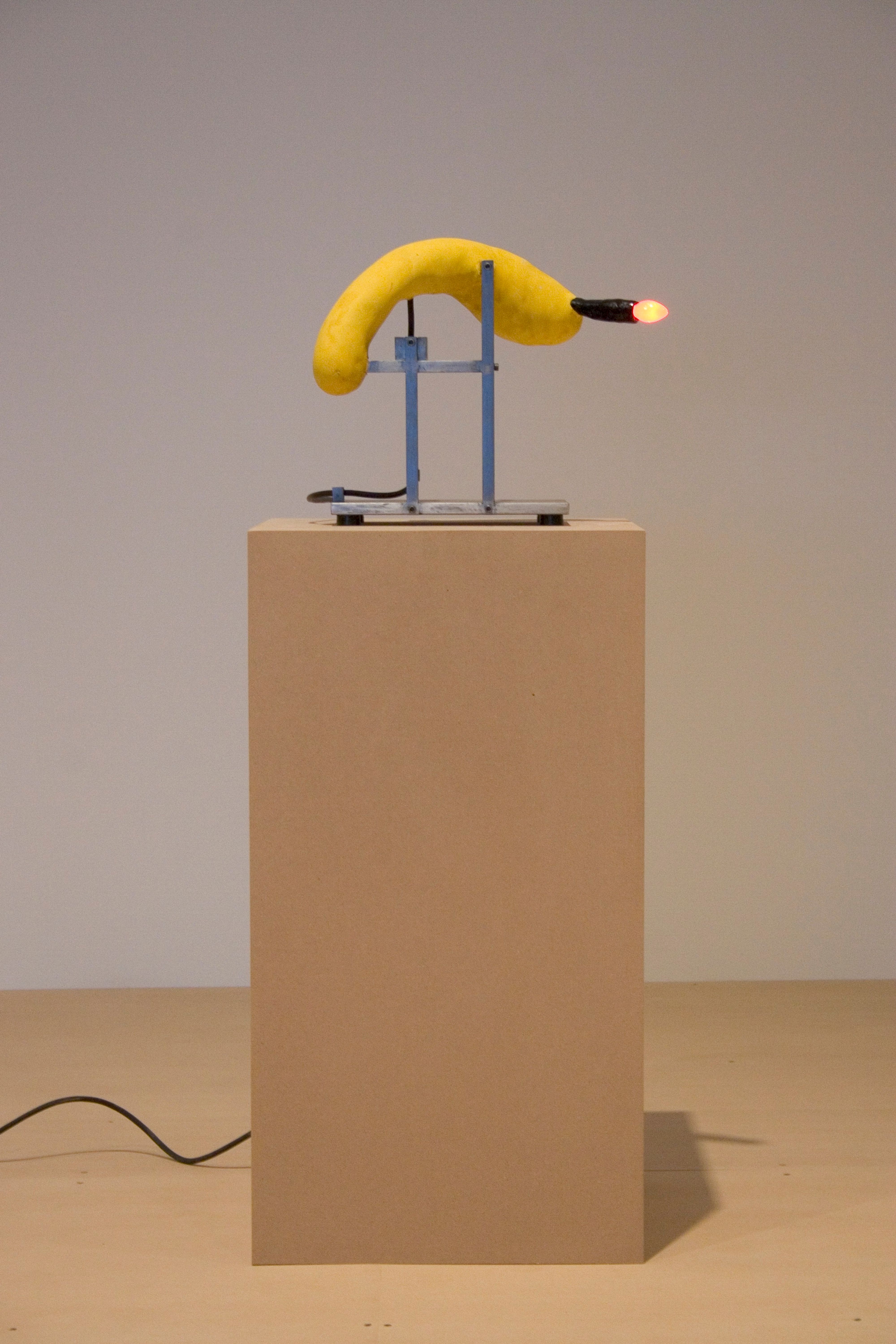

David Lynch, Love Light #2, 2022. © David Lynch, courtesy Pace Gallery.

David Lynch, Zebrawood Top Lamp, 2022. © David Lynch, courtesy Pace Gallery.

Consider David Lynch, lamp designer. In his Red Black Yellow Table Lamp (2011), a libidinal red pustule glows at the tip of a septic yellow phallus, fixed in place by an assemblage of orthogonal metal rods and plates. Its elegant brutality suggests Gerrit Rietveld-designed laboratory equipment. The lamp provides precisely enough light to be useless. On Planet Lynch, seeing clearly is less important than seeing with feeling.

Even people unversed in design history will notice Lynch’s unusual handling of the lamp’s cord. It seems to represent a restraining leash, as though to keep the phallus from wriggling away. On an overlapping wavelength, it expresses architectural Modernism’s fetish for control. Lynch’s cord — a loose, flaccid material — is disciplined by a series of rectilinear metal standoffs, which opens up a third reading: the cord as umbilical. It both supplies a vital current of electricity and it might be severed, setting free the phallus in question. Vitality, repression, architectural critique. What more can we ask of a lamp cord?

David Lynch, Red Black Yellow Table Lamp, 2011. © David Lynch, courtesy Pace Gallery.

A feeling of decisive precision pervades Lynch’s designs. There is a sense that his lamps have arrived at their forms through a process of calculated reasoning. This impression rubs against the precarity of many of his structural choices — in which ad hoc solutions just short of bubble gum hold things together. See, for instance, Love Light #2 (2022), in which the transition between the joined wooden rod and the lightbulb fixture appears to be a wadded smush of epoxy clay.

Lynch is a quixotic individual. For about nine hundred consecutive days he maintained a YouTube account dedicated to two jaw-droppingly mundane daily video series, produced by the auteur with what appears to be a foggy phone camera. In the first series, he picks “today’s number” out of a jar, announcing it with utter sincerity before finishing his script with the text overlay “WHAT WILL TOMORROW’S NUMBER BE?” These videos are as uninterpretable as the portions of his films that critics alternately describe as “inscrutable,” “self-indulgent” and “savagely uncompromising.” Perhaps predictably, they have their own cult following — with initiates creating highly involved interpretations and representations of the selected numbers. In the second series, Lynch provides the daily weather report, interspersing observations like, “It looks like these clouds are going to remain until late afternoon,” with such ponderings as: “I’m thinking about tree trunks and epoxy.” This banality is its own kind of provocation from a man better known, in his precocious youth, for making the film Blue Velvet, in which a psychotic lunatic in a bolo tie opens a scene with, “Shut up! It’s daddy you shithead!”, before huffing nitrous oxide and spluttering on the ground, rising to his knees, demanding his blackmail victim spread her legs, and plaintively addressing her vagina as “mommy” while proceeding to rape her. Lynch also founded a school of transcendental meditation.

The impulse to associate Lynch’s films with his furniture designs may at first seem specious, but as a director he often replaces narrative logics with choreographed atmospheres in which lamps, curtains, and characters diffuse into mood. These moods can be so engrossing that you simply forget, moment to moment, that you don’t know what is going on — or that such knowledge becomes insignificant in comparison to the overwhelming stimulation of the sensual input. In Inland Empire, long shots of ominously amber-colored lampshades are central to the creeping sense of menace. Some of Lynch’s directorial fixations with objects and interiors might be ascribable to his admiration for another filmmaker, the French comic master Jacques Tati. Tati’s crowning achievement, Playtime, is spun out from nothing more than the disastrous interactions between a protagonist and squeaky International Style chairs, anonymous office building façades, and impatient automatic doors. Modernism is the film’s sole antagonist and plot-driver.

David Lynch, Love Light #2, 2022. © David Lynch, courtesy Pace Gallery.

David Lynch, Clear Top Lamp, 2022. © David Lynch, courtesy Pace Gallery.

Lynch has a keen sense of how small changes to the familiar can detonate cataclysmically. Throughout Eraserhead, a plant sits on the protagonist’s bedside table without a pot. What is a potted plant without its pot? Ungoverned nature: something which can, if not suppressed, destroy an entire house, an entire city. Nothing more than a ceramic shell insulates cozy domesticity from this whirlpool of anarchy, atavism, and ominous possibility.

David Lynch is a world maker — and what that means, critically, is that he is not above being a lamp maker. A separate question to puzzle over is why any lamp maker would not have designs on the world. A room, after all, shapes the presence of the lamp. And rooms are modeled by the spaces which precede them, the spaces that enmesh them, and the glimpses they offer of what lies beyond. Our perceptions of luminosity and color temperature are connected to the natural light conditions at a given moment, so a skilled lamp designer may need to adjust the sun to better suit the lamp.

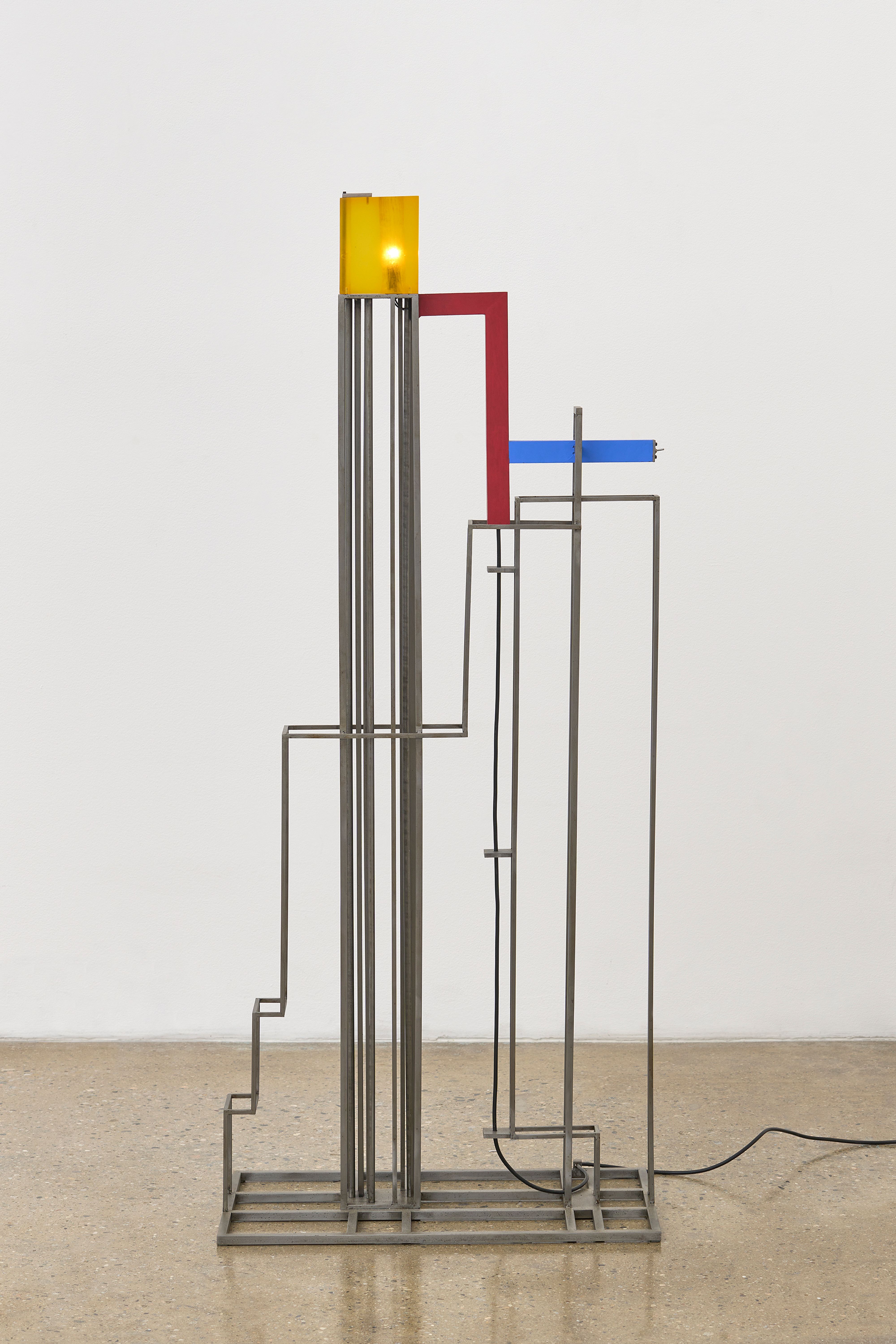

David Lynch, Tricolor Highrise Lamp, 2022. © David Lynch, courtesy Pace Gallery.

In interviews, Lynch has expressed a fondness for the Bauhaus. Like other modernisms, that movement was distinctly utopian — it took as a premise that design might reshape humanity at large. It was also a set of aesthetic preferences: rectilinearity, primary colors, expressive structures, undisguised joinery. All of these can be found in Lynchian works including Tricolor Highrise Lamp (2022). Lynch peels away Modernism’s performative rationalism and relishes its underlying craziness — in which repression descends into fetish. Think of Adolf Loos’s lush, carpeted interiors in relation to his stark raving mad anti-ornamentalist invectives (see his “Ornament is Crime”). Lynch too has utopian inclinations. He says his mission in founding a school of transcendental meditation is to lead humanity into an “ocean of pure, vibrant consciousness.” Out there, in the ocean, the light looks strange.