Mirrored Ball Ornament, date unknown; Mirrored plastic, foam, and string. Bruce A. Goff Archive, Ryerson and Burnham Art and Architecture Archives, The Art Institute of Chicago.

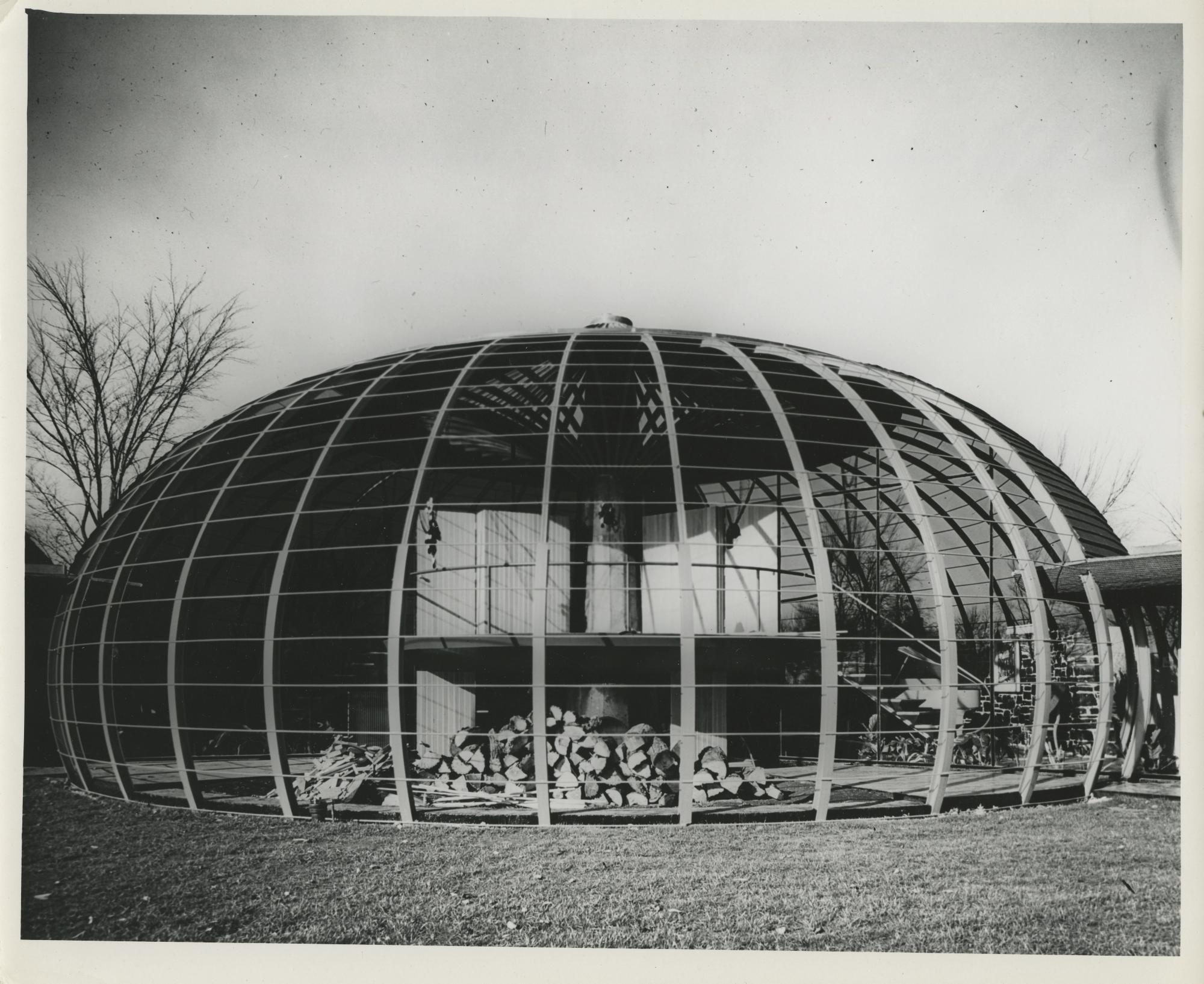

Glen and Luetta Harder House, Mountain Lake, Minnesota, 1980. Photograph by Julius Shulman. © J. Paul Getty Trust. Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles (2004.R.10).

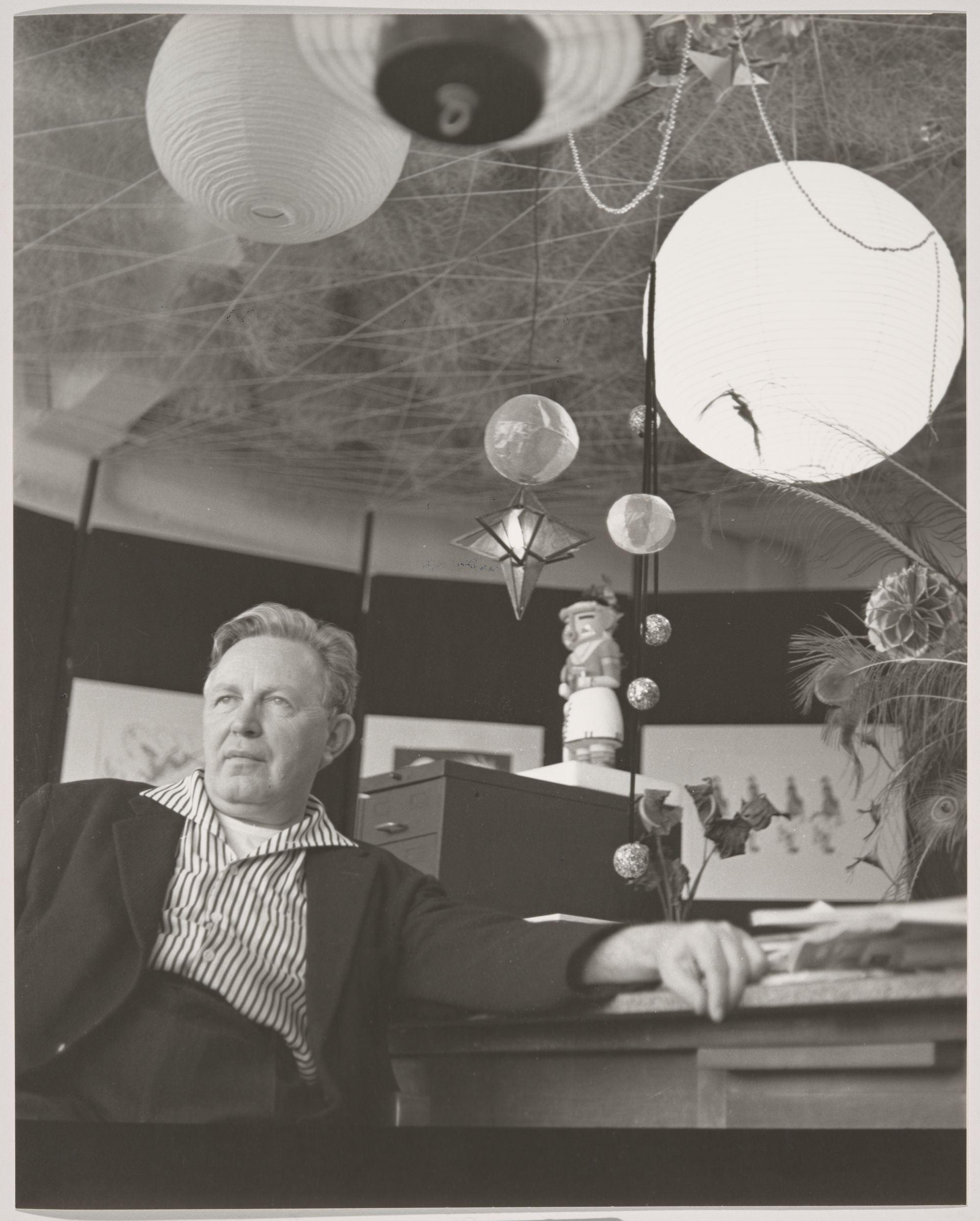

Shocking architecture eventually fades into the background. Like electricity or the automobile, modernism has been so thoroughly digested that it can be difficult to understand how new and radical it once felt. The work of Bruce Goff is different. Instead of looking commonplace, his endlessly inventive buildings from the midcentury seem stranger than ever. A young savant who got his start in design as a teen, Goff began an early correspondence with Frank Lloyd Wright, who encouraged him to preserve his wild imagination by avoiding a formal East Coast education. Instead, he stayed in Tulsa, drawing from the city’s thriving artistic scene before moving to Chicago to teach and open his own practice in 1935. Deployed in the Navy in 1942, he found new ways to use his skills, creatively reworking quoinset hut frames to form a chapel, bringing out beauty latent in the mundane. Landing back in Tulsa after the war, Goff embarked on a series of unique residential commissions throughout the Midwest. Colorful, twisting villas made of collages of unusual materials like ashtrays and tinsel, these exuberant works pursued a new architectural American vernacular, combining technological optimism, roadside novelty, and the overabundance of consumer culture. Over nearly a decade as its chairman, Goff reshaped the University of Oklahoma’s architecture school, influencing a generation of designers before being pushed out by McCarthy-era persecutions of gay individuals in positions of power. His extensive archives, art collections, and personal effects were donated to the Art Institute of Chicago, where Bruce Goff: Material Worlds, curated by Alison Fisher and Craig Lee, is on view from December 20, 2025–March 29, 2026. The exhibition is designed by the New York-based firm New Affiliates, who spent months diving into Goff’s legacy to develop a show that could bring the vibrancy of his spaces to this eclectic archive. Below, New Affiliates principals Ivi Diamantopoulou and Jaffer Kolb share how the show and Goff’s little-seen work could influence a new generation of American architects.

Exhibition view of Bruce Goff: Material Worlds at The Art Institute of Chicago, designed by New Affiliates.

Mirrored Ball Ornament, date unknown; Mirrored plastic, foam, and string. Bruce A. Goff Archive, Ryerson and Burnham Art and Architecture Archives, The Art Institute of Chicago.

Exhibition view of Bruce Goff: Material Worlds at The Art Institute of Chicago.

Oscar Peña: You’ve designed exhibitions about history, art, music, and film, but one of the challenges of an architecture show is communicating spatial properties. How did you approach that challenge of representation?

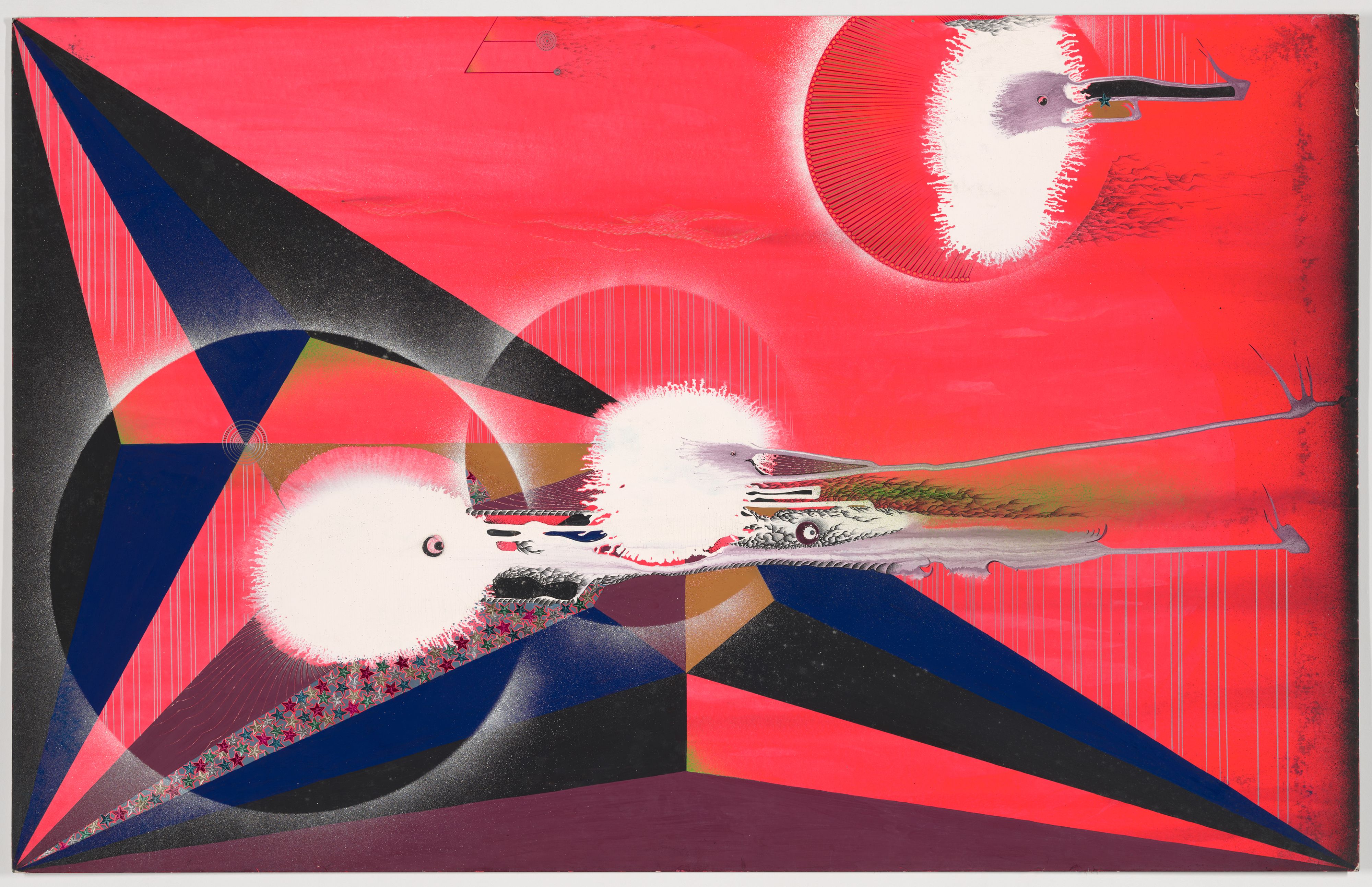

Ivi Diamantopoulou: I feel like we’ve always had a little bit of an excuse when curating. We’re not art historians. But here it felt too close to home to not take a position on this alongside the curators. On Tumblr, you’d find snippets of his work, just one or two out-of-context images, so I always thought of the work as image-based. When I dove into the exhibition material, I realized how radically different from Modernism his work really was. Planometrically, his buildings and homes are organized differently: no thresholds, no defined rooms. There are familiar 1950s and 60s details, but all the Modernist tropes — continuity, sightlines, alignments — are actually completely dematerialized.

We imagined the exhibition as a series of slippages, where even though the exhibition is organized into eleven episodes of Goff’s career, you’re never totally enveloped by one. You’re always between periods, getting a glimpse at what comes ahead. You’re in this ambiguous space between his built work and his speculative work, always anchored by his paintings.

Living Room of Etsuko and Joe Price House, Bartlesville, Oklahoma, 1972. Photograph by Horst P. Horst for Vogue.

Myron Bachman House, Chicago, Illinois, date unknown. Photograph by Don Tosi. The Art Institute of Chicago, Ryerson and Burnham Art and Architecture Archives, Bruce A. Goff Archive.

Ruth and Sam Ford House, Aurora, Illinois, date unknown. Photograph by Wayne W. Williams. The Art Institute of Chicago, Ryerson and Burnham Art and Architecture Archives, Bruce A. Goff Archive.

Jaffer Kolb: We also used these sectionally stepped platforms and display surfaces that recalled the midcentury interest in floors and walls that act as embedded furniture.

ID: It’s difficult to put furniture on a pedestal without it looking like a store. It felt nice to bring more domestic architecture into play. That’s how the stacked platforms came to be: looking at some of Goff’s conversation pits or sunken hallways. The floor raises itself for you rather than a pedestal that’s a discrete object.

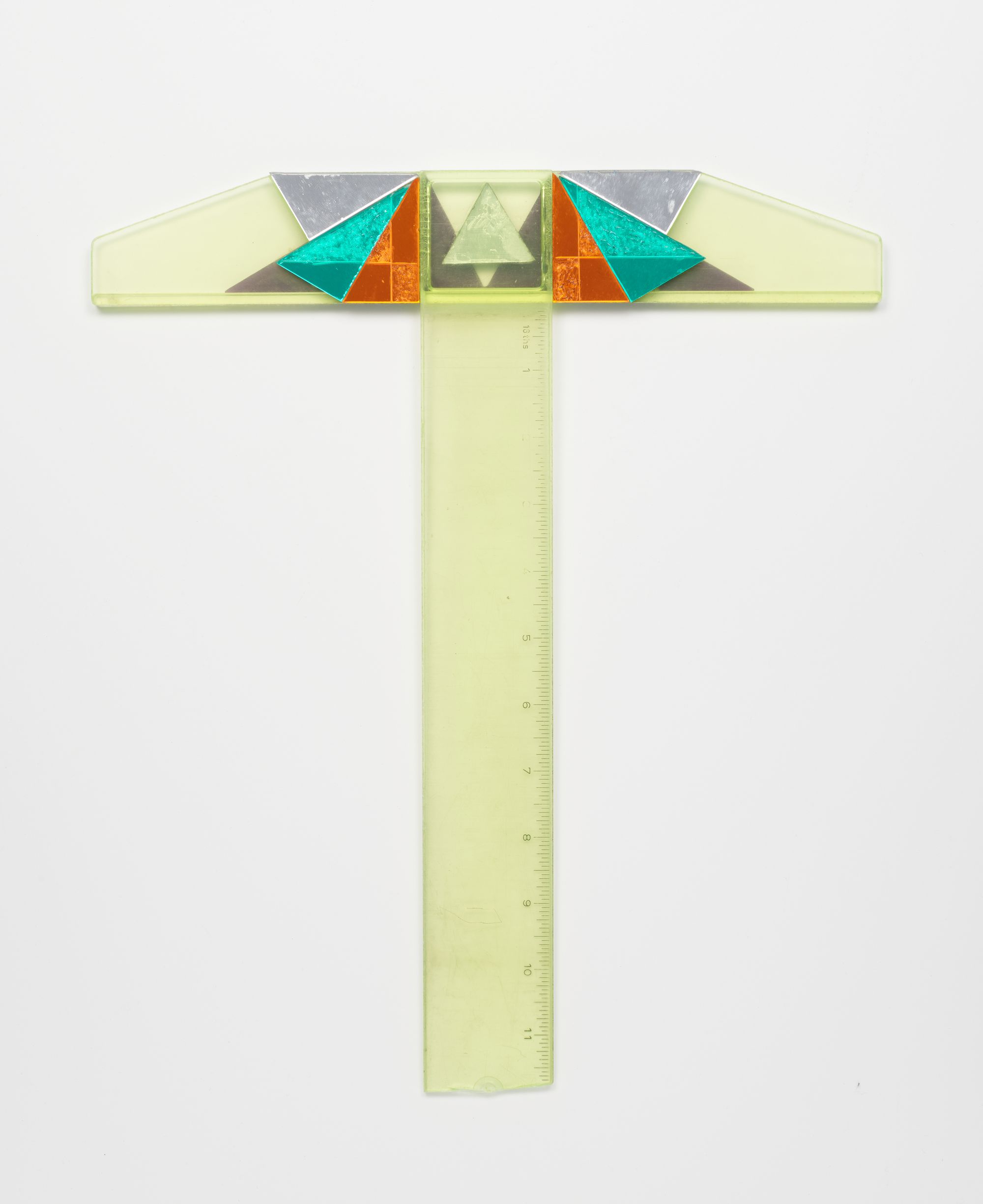

JK: Architecture can’t be communicated only through models or drawings or photographs. One thing that’s interesting about Goff is how much the spatialization of the work is contingent on the materials. Between a model, a drawing, and a painting, you might get three material samples, like a carpet tile or a little hanging ball lamp. For some architects that wouldn’t really communicate what their work was about, but for Goff, it does. By juxtaposing materials with more typical architectural representations, we can produce some kind of spatial consequence or configuration.

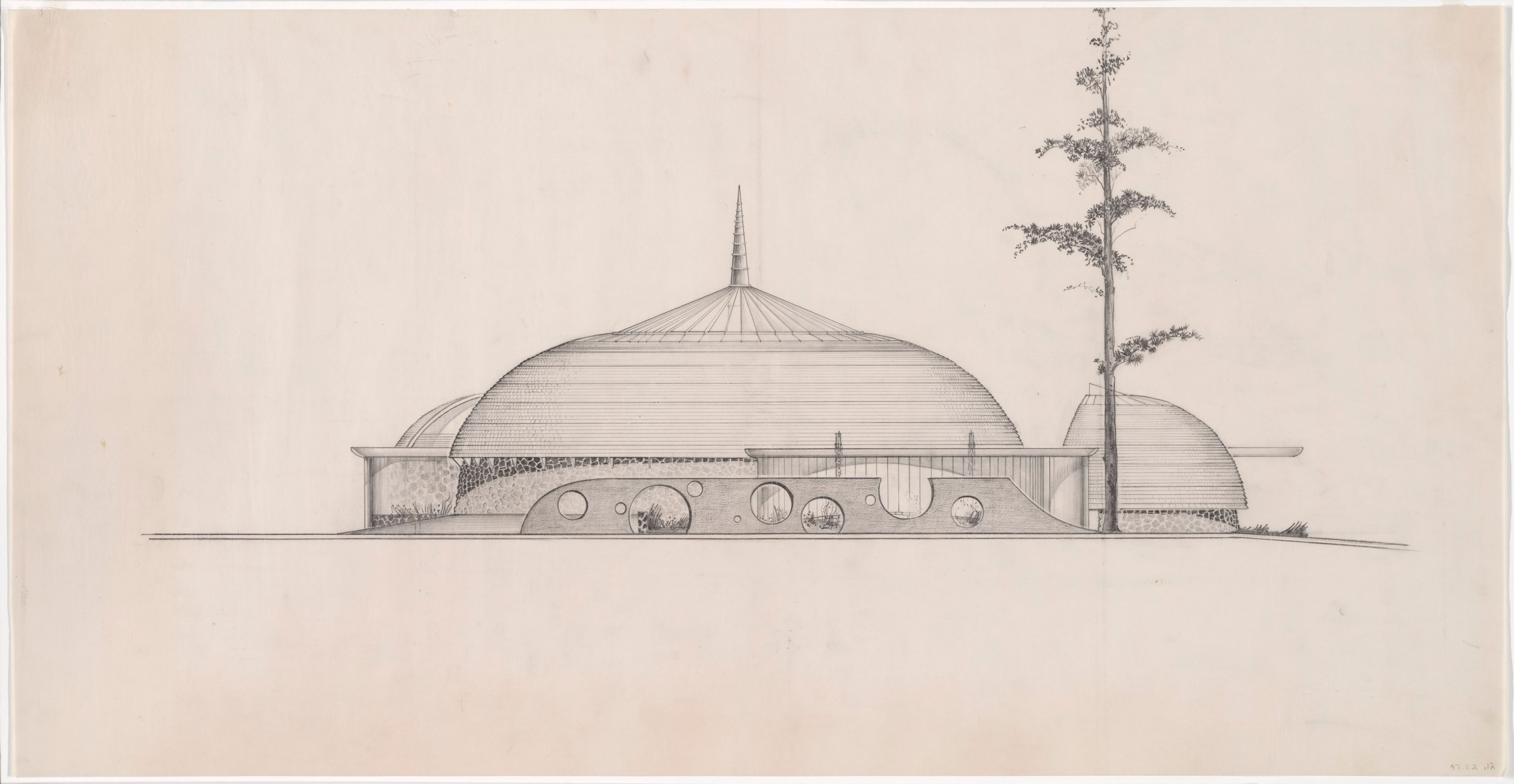

Bruce Goff, Viva Casino and Hotel, Las Vegas, Nevada, Perspective [unbuilt], 1961. The Art Institute of Chicago, gift of Shin'enKan, Inc.

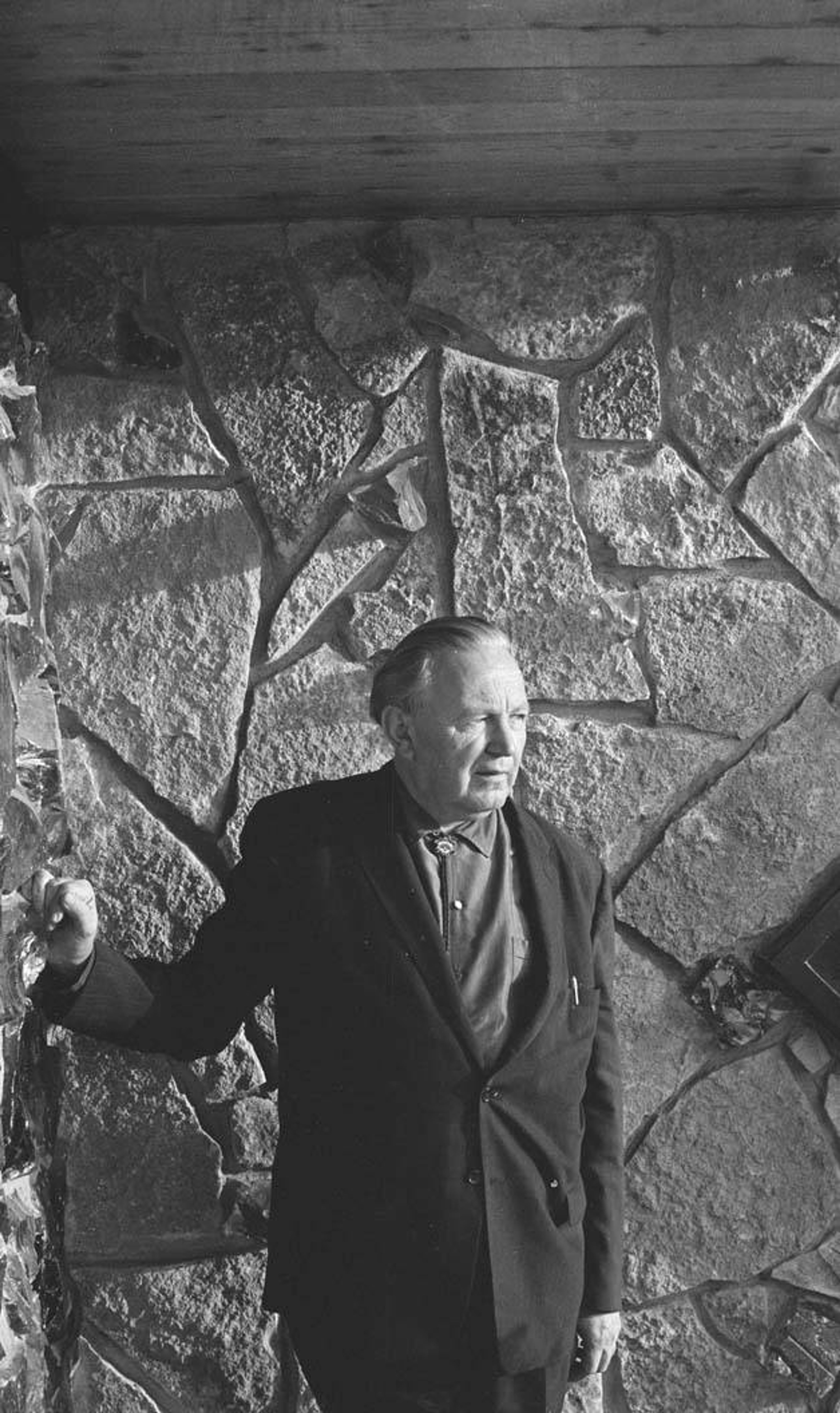

Bruce Goff in his Office at the University of Oklahoma, about 1954. Photograph by Philip B. Welch. The Art Institute of Chicago, Ryerson and Burnham Art and Architecture Archives, Bruce A. Goff Archive.

Bruce Goff and Herb Greene, Eugene and Nancy Bavinger House, Norman, Oklahoma, Elevation, 1950. The Art Institute of Chicago, gift of Shin’enKan, Inc.

It’s very rare for a museum to accession all of those “non-art” materials. The architectural historian Sylvia Lavin talks about this distinction between the flat file and other archives, where people are always looking at architects’ drawings, but a lot of how a design comes together is revealed in other correspondence and ephemera. The Art Institute kept his seashells, record collection, his clothing — how did you think about building an environment where those two categories could be in conversation?

JK: The first thing you see when you walk into the gallery is a tiny, mirrored disco ball. It’s a little artifact that produces this refracted light. Entering into a materially conditioned space is such a Goff move.

ID: There’s an aesthetic regime in Goff’s universe. It’s not just work; it’s the way he exists in the world. You see these little objects, but then you also see his collections of non-architectural materials — dolls, indigenous artifacts, his obsession with Japanese prints — and you start to see the way he designs and how he is in the world. But that was extremely difficult: how do we make this feel like a point of entry and not a little junkyard? We tried to amplify their presence. Every one of his objects has its own plinth. Before seeing much of the architectural work, it asks you to immerse yourself in a material world.

JK: We wanted to ensure that the artifacts weren’t isolated, but always seen through, against, and between other forms of more typical architectural representations. The fact of the matter is that Goff’s drawings were not sufficient to build buildings. A huge story about Goff is the labor. With the Bavinger House, his clients were two artists, and they used students from the University of Oklahoma to build it. They were all onsite figuring it out as they went along. As a way of designing and building it’s so novel and special, and that cannot be communicated through typical plans and sections.

ID: For example, we visited this one project of his, the Ford House. We had studied the house and seen all of the drawings, but when we walked in, it was nothing like we’d imagined. It’s really magical. You walk into the house and the first breath you take, you can smell the rope-clad ceiling after all these years. Even talking to the current caretaker of the home, there’s an intensity to living in a home that is so ad hoc. He had this amazing story of how Goff would show up and stick the marbles in the wall himself.

JK: Many of the houses were off the beaten path, done with clients who didn’t want typical contractors. I think that it ties into radical fairy stuff in the 70s. D.I.Y., figure it out. It’s highly idiosyncratic and only possible through the accumulation of different laborers that come together without a delineated plan. Building as an act of sociality, a barn raising. It’s roadside Modernism meets a quasi-rural collective building project.

Exhibition view of Bruce Goff: Material Worlds at The Art Institute of Chicago.

Bruce Goff. T-Square with Mirror Mosaic Pieces, date unknown. Private collection.

Bruce Goff. Folding Screen for the Myron Bachman House, Chicago, Illinois, 1942. The Art Institute of Chicago, gift of Sidney K. Robinson.

Goff mainly operated in Oklahoma and the interior of the country, away from larger cities that would’ve connected him to the field’s mainstream. He was intentionally provincial. What struck you about this regionalism and how it impacted his work?

JK: The postwar period had this proliferation of new industries and material systems that architects were exploring, like aluminum or bent plywood. But with Goff there was this directness, like taking the Quonset frame and turning it into the frame of the Ford House. He wasn’t looking at industrialism or technology at large, which are intellectual abstractions. He was someone in a place, looking around for himself and figuring out how this new world would inflect the actual materials, the labor of construction, and its formal outcomes. And I think that couldn’t have really happened anywhere else. I cannot imagine Paul Rudolph or Charles Moore going through that.

ID: What I find fascinating about him is that he’s able to detach himself from Wright at a moment when everyone is trying to be his protégé in Taliesin. Goff was able to cross paths with Wright but move away and do his own thing. I think that independence is so formidable as a maker and designer.

JK: But there was never any sense of negativity or critique in Goff’s writing or work. You never got the sense that he was reacting against Wright or industrial Modernism. He just seemed interested in trying stuff. He wasn’t like, “Modernists don’t use curbs, so I’m going to.” There was something in him that just wanted to make things instead of reacting against them.

Bruce Goff, Untitled (Composition), 1939. The Art Institute of Chicago, gift of Shin’enKan, Inc.

Bruce Goff, Untitled (Composition), about 1925, The Art Institute of Chicago, gift of Shin'enKan, Inc.

Bruce Goff, Untitled (Composition), 1939, The Art Institute of Chicago, gift of Shin’enKan, Inc.

Bruce Goff, Hopewell Baptist Church, Edmond, Oklahoma, Perspective, 1948–49. The Art Institute of Chicago, gift of Shin'enKan, Inc.

Taliesin is interesting because Goff was chair of University of Oklahoma’s architecture department and developed his own group of protégés called the “American School of Architecture.” He rejected both the Beaux-Arts model and the Bauhaus model of education. As educators, what did you think about his teaching activity?

ID: Schools have now evolved to be a bit of a catchall, where you get multiple orientations, and you can try a little bit of everything and situate yourself in a wider landscape. There’s a lot less of a dogma, and much more opportunity for dialogue and different ways of thinking. It’s something that I appreciate about American education in particular. You don’t have a generic system, but a lot of people coexisting.

JK: One of the things architecture education suffers from is an insistence that everything has to have a thesis or argument. The argument-as-architecture was so ingrained in me and I feel like I’m constantly trying to break myself of that habit. The model that Goff taught and practiced was much more about the transdisciplinary act of making and assembling things. He was a prolific painter. He was obsessed with music and poetry. He had this polymathic approach that privileged doing stuff and making sense of it, which is how his buildings evolved as well — as crafted things. We’ve moved away from that, and it’s nice to be reminded that there’s an alternative.

Ruth and Sam Ford House, Aurora, Illinois, date unknown. The Art Institute of Chicago, Ryerson and Burnham Art and Architecture Archives, Bruce A. Goff Archive.

Exhibition view of Bruce Goff: Material Worlds at The Art Institute of Chicago.

Exhibition view of Bruce Goff: Material Worlds at The Art Institute of Chicago.

You also did some Goff-inspired drawings for the show. Can you tell me about those?

JK: We thought we would make these three drawings of different houses, tracking their material histories. Ekin Bilal on our team studied graphic novel traditions and led this drawing project with us, so that factors into this final representation. We were trying to operate between architectural drawing conventions and storytelling.

ID: And maybe unlock a different way of reading the houses, because the form is always so dominant when you look at these structures. It’s very hard to see past the Bavinger House’s spiral, so we unrolled the spiral to call out the genesis of the many materials that came into the project.

JK: Starting with lumber from this tree and then blowing up rocks to form the exterior walls.

ID: His students are there mining the rocks on the site.

JK: Which was actually what happened.

There’s this quasi-ecological thing with the materials being collected so nearby the site.

JK: It’s a form of what Kenneth Frampton would call critical regionalism, except the region is not just about the sensitivity of certain organic materials or about the weirdness of industrial byproducts. So it was all hyperlocal, but it doesn’t obviously register that way.

ID: And the materials are very inclusive. Of course it’s postwar, so the oil industry and aircraft are present, but you also have fishermen’s nets. It feels additive.

JK: It’s a funny way to take military technology and turn it into this completely expressive, joyous outcome. Pure Goff.

Bruce Goff at Redeemer Lutheran Church and Education Building, c.1950s-1960s. The Art Institute of Chicago, Ryerson and Burnham Art and Architecture Archives, Bruce A. Goff Archive.