WRAP STAR: THE UNUSUAL FASHIONS OF ADELINE ANDRÉ

The building and rag trades have one fundamental point in common: their primary concern is the provision of a protective wrapping within which the human body can operate. Both industries run the gamut from the mass produced to the bespoke, the dowdy to the fashionable, the generic to the unique art object, and both employ intellectuals to bring artistry to the craft, calling them architect and fashion designer respectively. While fashion designers mostly keep stumm about architecture, architects sometimes sound off about fashion, most notably Adolf Loos, whose strange rants on topics such as gentlemen’s hats, shoemakers, or the English uniform dwelt essentially on the moral implications of external appearances (a manifest concern in his buildings) rather than the practical parallels between the disciplines: the enveloping of the body in ways that facilitate or restrict movement, that make one conscious or unconscious of that movement, and that cause one to feel formal or informal, beautiful or plain, workaday or exceptional.

For Loos, writing in 1898, “The best tailors throughout the world, the ones capable of outfitting someone according to the principles of true elegance, can be counted on the fingers of two hands.” Were he alive today, one suspects he might number Paris-based haute-couture designer Adeline André among them. Dubbed the “mother of minimalism” by The New York Times in 1986, her clothes display a truthfulness to materials, an eschewal of decoration, and a wealth of conceptual detail that could only have delighted the author of Ornament and Crime. As André herself put it: “In 1981 I founded my company with Istvan Dohar, an interior designer, and Nicolas Puech, and very naturally our work focused on the essentials: the cut, the construction, the fabric. We avoided ‘decoration.’ The tactility and intrinsic qualities of every fabric are interesting, from the heavy scratchiness of Harris tweed to the lightness and transparency of silk organza, the crinkly sheerness of crêpe georgette to the soft smooth weight of doeskin. It’s the fabric itself that gives the structure — I’m not at all interested in twisting it out of shape or supporting it artificially. I like it when all that’s seen is all that’s there.”

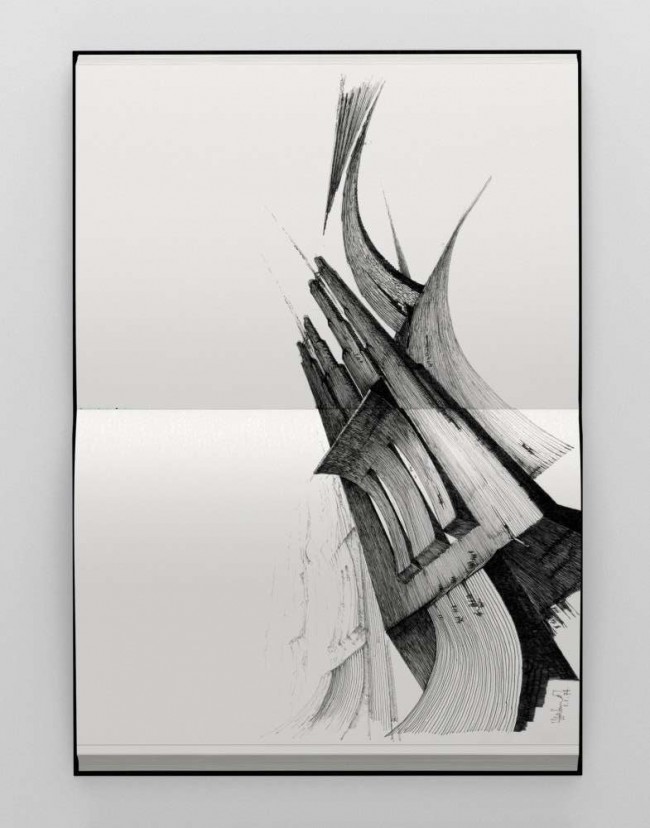

Architect and historian Philippe Duboÿ, who began his career as Carlo Scarpa’s assistant, says that were he to compare André to an architect it would definitely be Loos, although he might define her output as Vienna viewed through Venice given her Scarpa-esque penchant for the telling detail. For Duboÿ, André’s work recalls Loos’s in that at first glance it seems simple, but there is a refinement of thought and detail belying initial appearances. Duboÿ, who met André at the beginning of her solo career, has long been a devotee of her three-sleeve jackets, a design she has patented and which is typical of her approach: garments that do up without buttons, zips, or fastenings of any kind. André uses the three-sleeve system not only for men’s jackets but also for ladies’ coats and dresses, and pushed the concept to its extreme with the 21-sleeve dress she (literally) unveiled at her fall/winter-2009 show, when she slowly spun the runway model down a gauze-hung clothes line.

Architect, urbanist, and landscape designer Alexandre Chemetoff is also a longstanding member of the three-sleeve club, and his collection of jackets dates back to the 1980s. Many of them have become torn and threadbare, but rather than throw them away he has had André repair them in a manner that recalls his own landscape work at recycled industrial sites, where he has patched together the new and the old in narrative dialogue. For Chemetoff, the beauty of André’s work lies in her total commitment to her art, pushing the logic of her ideas to its extreme, as well as in her approach to material. An example he cited was her frequent choice of double-layer fabric, which allows her to create invisible hems by separating the layers and folding them inwards. In this, André’s work is reminiscent of Bauhaus approaches: students on Josef Albers’s preliminary course undertook exercises in the nature of materials, for example producing self-supporting paper sculptures without using glue or producing any off cuts; likewise, André, from a desire to avoid joins and stitching, creates highly sophisticated patterns where one piece of fabric forms a dress or coat with integral belt and pockets that are not tacked on afterwards but are a seamless part of the whole. Her work is also reminiscent of the architectural avant-garde in its use of color: her shades and combinations are as surprising as Le Corbusier’s and, like his, intended to liberate emotion.

At the Renaissance, Italian intellectuals theorized an ideal architecture whose proportions, based on the human body (Vitruvian man as drawn by Leonardo et al.), would govern all the parts so that, in Alberti’s famous definition, nothing could be added or taken away without destroying the harmony of the whole. It is in this spirit that André conceives her clothes: perfectly proportioned creations entirely calibrated on the body (limp phantoms on the hanger, André’s garments spring to life when worn) where absolutely nothing is superfluous. The result is a breath-taking simplicity of line that belies the years of research that went into perfecting it. But for André, her art is like song or ballet: “One must never feel the effort — only pure emotion should remain.”

Photography by Matthieu Lavanchy.

Adeline André's 21-sleeve dress is currently on view as part of The Overworked Body: An Anthology of 2000s Dress at Mathew Gallery in New York.

Taken from PIN–UP 14, Spring Summer 2014.