Michael E. Smith, Untitled, 2024; basketballs, urethane, foam epoxy. 17 x 14 x 11 in. Photography by Sean Davidson.

Exhibition view of Weekend Tournament photographed by Sean Davidson.

Ninety years after Le Corbusier, Charlotte Perriand, and René Herbst unveiled The Young Man’s Home at the 1935 Brussels International Exposition, Raquel Cayre and Ariel Ashe have written its sequel. Their exhibition Weekend Tournament, spread across sixty objects throughout Raisonné’s 16 Crosby Street gallery, functioned as both homage to and autopsy of Modernism’s “intellectual athlete” — that curious hybrid who believed barbells and bookshelves were natural roommates, that the gymnasium and the study could coexist in perfect harmony.

Where The Young Man’s Home promised integration, Weekend Tournament delivered fragmentation with a wink. The original apartment-gym hybrid was dead serious about its mission: to demonstrate that modern living meant treating your home like a training facility for life itself. The medicine ball was a meditation prop, the rowing machine was kinetic sculpture, physical and mental cultivation were teammates rather than competitors. It was Modernism at its most earnest, convinced that the right environmental design could manufacture better humans.

Michael E. Smith, Untitled, 2024; basketballs, urethane, foam epoxy. 17 x 14 x 11 in. Photography by Sean Davidson.

Exhibition view of Weekend Tournament photographed by Sean Davidson.

Sam Stewart, Ping-Pong Table, 2025; HPL, sapele. 108 x 60 x 8.5 in. Photography by Sean Davidson.

Weekend Tournament took this premise and lovingly dismantled it, piece by piece. The curators framed their show as a “field of action,” but it’s a field where the game has fundamentally changed. Rachel Harrison’s FCHEM (2016) exemplifies this shift perfectly: a sculptural assemblage that incorporates gymnastic rings, jump ropes, and fitness balls alongside cement, burlap and heavy metal chain. Gym equipment or torture device? From a distance it feels tempting to use, but, upon closer inspection, its utility is illusory.

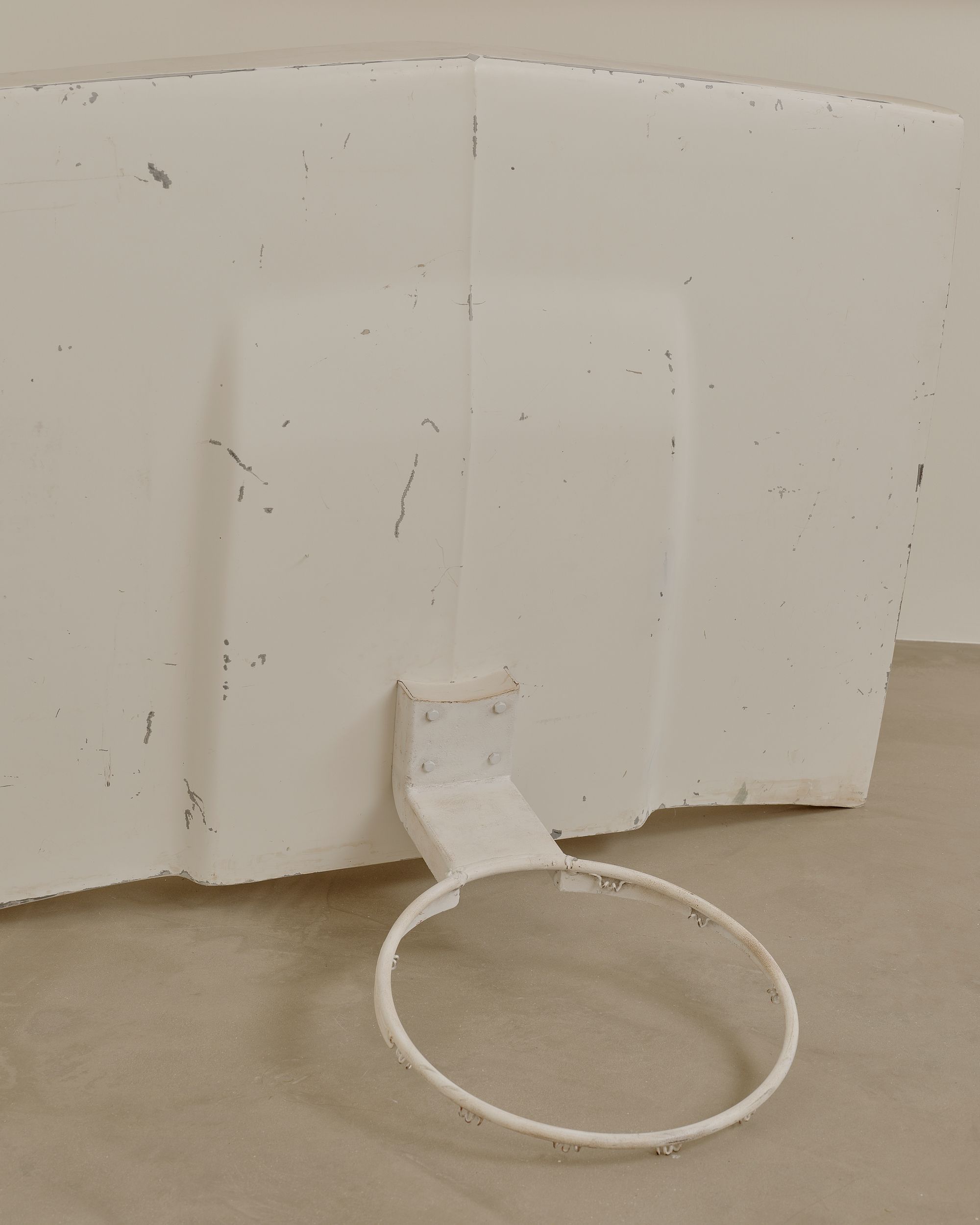

The exhibition’s standout piece makes this ghostly absence literal. Richard Prince’s rarely exhibited Untitled (Backboard) from 2008, on loan from the artist’s personal collection, presents a basketball hoop attached to a disembodied, crudely painted car hood that leans precariously against the gallery floor. It’s a masterpiece of dysfunctional sculpture — it carries the residue of its original function while being completely emptied of purpose, like finding a severed limb that still twitches with muscle memory.

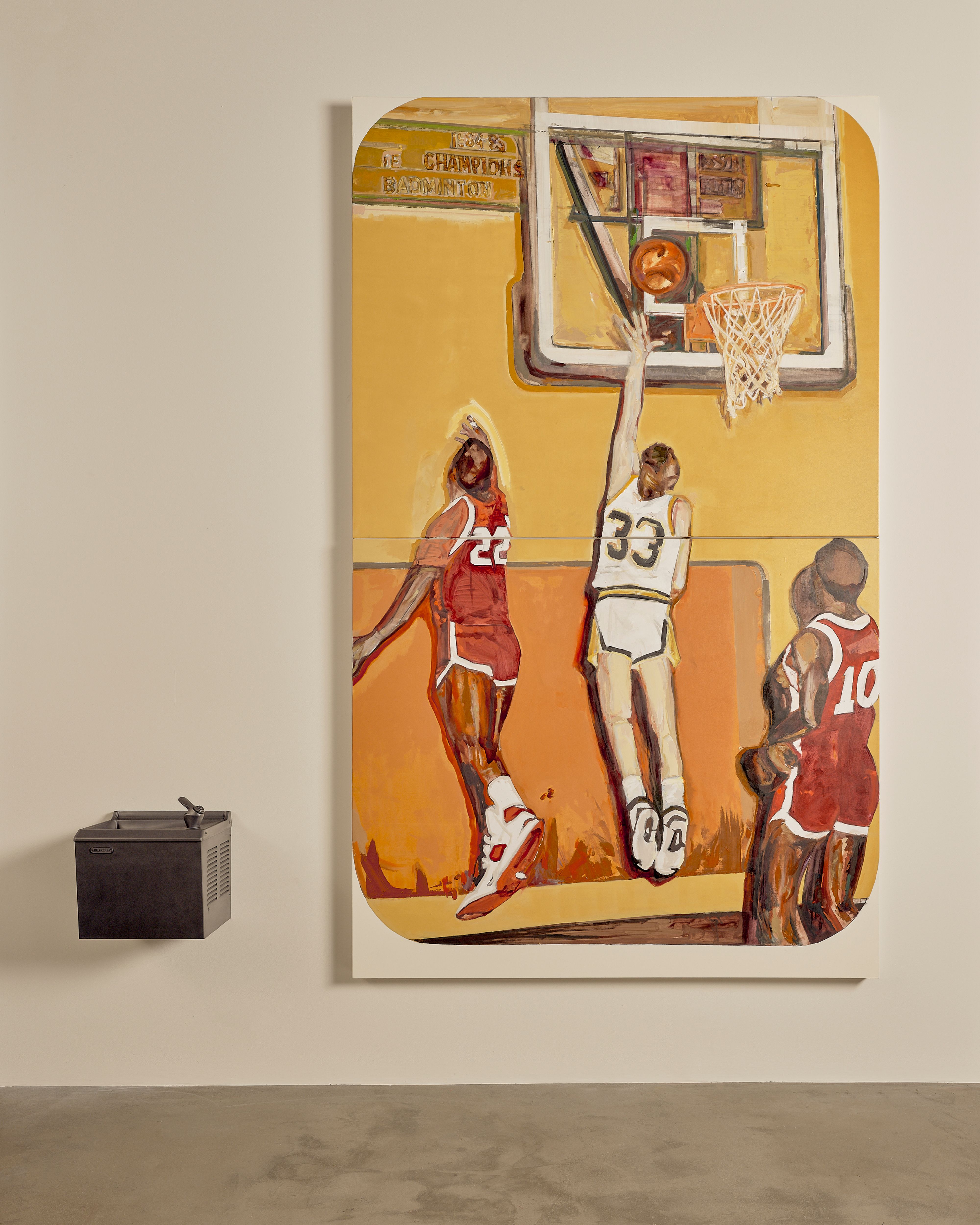

This aesthetic of beautiful dysfunction runs throughout the exhibition. Michael E. Smith encases basketballs in urethane foam (Untitled, 2024), creating fossilized sporting goods that look like archaeological artifacts from a civilization that once played games. Fernando Marques Penteado covers tennis rackets in intricate embroidery (Oleg Ivanhof [OI], 2019 & Enrico Carone [EC], 2019) spelling out player names in ballpoint pen and thread — gorgeous objects that would disintegrate if you actually tried to hit a tennis ball with them. Charlie Koss arranges tennis balls in sculptural systems called 72 Unforced Errors, (2025) cataloging athletic failure rather than celebrating athletic achievement. Each work carries that same quality as Prince’s backboard: the memory of function wedded to the impossibility of use.

Jake Clark, Clay court, 2024; glazed earthenware. 14 x 12 x 2.5 in., on top of Vicente Muñoz, Lawn Tennis Table, 2025; maple, stainless steel, urethane. 21 x 25 in. Photography by Sean Davidson.

Right: Le Corbusier, LC II Sconces, n. d; green Patina finish. Bottom: Will Gisel, Bellwether, 2025; birch, turf, stainless steel, acrylic. 368 x 43 in. Photography by Sean Davidson.

Sam Stewart, The Marty Cabinet, 2025; Plywood, paint. 66 x 23.5 x 6 in. Photography by Sean Davidson.

The exhibition’s most telling contrast came from placing a pommel horse attributed to Pierre Jeanneret (ca. 1960) from the Punjab University gymnasium in Chandigarh alongside contemporary works like Chadwick Rantanen’s Telescopic Pole (2016). The piece was built for actual gymnasts within Le Corbusier’s grand architectural vision — it embodies The Young Man’s Home’s earnest functionalism. Rantanen’s work uses tennis balls and walker balls as adjustable sculptural components that you can reconfigure endlessly, but not for any athletic purpose.

Weekend Tournament reveals what happened to the intellectual athlete: he became the quantified self, then he disappeared entirely. The most striking aspect of the exhibition isn’t what was present but what was conspicuously absent — bodies. In this sea of athletic equipment, the human form exists only as phantom, suggested by the negative space where flesh and bone once engaged with all these carefully preserved implements.

Two works make this absence playfully clear. Sam Stewart’s The Marty Cabinet (2025) takes the shape of a striped shirt tucked into a pair of wooden trousers — a cabinet masquerading as a hollow athlete. Evoking the sensual flatness of Domenico Gnoli’s sartorial portraits, it’s also an homage to ping-pong champion Marty Raisman (who’s having quite a cultural moment, with Josh Safdie’s biopic starring Timothée Chalamet arriving later this year), but more than that, it’s a perfect metaphor for contemporary sports culture: all the gear, all the style, but the body has vanished into abstraction. Al Freeman’s Softer Dodgers Jersey (2024) compounds this ghostliness — an oversized uniform suspended from the gallery wall like sporting goods from the afterlife.

Display of World Tennis Magazines curated by Pro Shop NYC. Photography by Sean Davidson.

Paul Pfeiffer, Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse (11), 2004; Fujiflex digital c-print, in artist’s frame. 56 x 68 x 3 in. Photography by Sean Davidson.

Exhibition view of Weekend Tournament photographed by Sean Davidson.

Rachel Harrison, FCHEM, 2016; wood, steel, aluminum, stainless steel, gymnastic rings, straps, jump rope, chain, fitness ball, wood, polystyrene, cardboard, cement, burlap, acrylic. DIY gym: 98.5 x 87 x 70 in; orange kettlebell: 29.5 x 23 x 23 in. Photography by Sean Davidson.

Exhibition view of Weekend Tournament photographed by Sean Davidson.

The show treated athletic equipment like museum artifacts, and perhaps that’s exactly what they’ve become. Vintage medicine balls and parallel bars shared space throughout the gallery, creating an environment where bodies existed only in suggested absence. In our screen-heavy world, sports remain one of the few places where bodies still matter in straightforward ways. But Weekend Tournament suggested we’ve moved beyond even aesthetic appreciation — we’ve arrived at equipment designed for bodies that never show up.

The transformation from The Young Man’s Home to Weekend Tournament tracks a broader cultural shift. The 1935 apartment promised that the gym’s honest transactions — effort, improvement, measurable progress — could be integrated into daily life. Instead, daily life now operates according to the gym’s logic without the gym’s rewards. We have home gyms bristling with monitoring devices, boutique fitness studios that function like secular cathedrals, and Peloton bikes that transform exercise into aspirational media consumption. The intellectual athlete evolved into something he probably wouldn’t recognize: a figure obsessed with optimization data but increasingly removed from actual physical engagement.

But Weekend Tournament offered one fascinating exception to this pattern of dysfunction. Nestled within the gallery was a bespoke regulation size ping-pong table, painstakingly turned by Sam Stewart, perpetually in use, with scores covering the nearby backboard leading to a fictive pro shop, stocked and overseen by Vicente Munoz, the proprietor of New York’s Pro Shop. Here, among carefully sourced vintage tennis uniforms, ceramics, and a magazine stand filled with niche sports publications from a bygone era, Muñoz turns the restringing of rackets into a delicate ballet. It’s the only space in the exhibition where athletic equipment retained its functional purpose, where the promise of actual play remains alive.

From top to bottom: Le Corbusier, Applique murale, vers 1954–1955; Tôle d’acier peinte, aluminium embossé, verre et laiton/painted sheet steel, embossed aluminium, glass and brass. 8.63 x 22.88 x 13.38 in. From the collection of Jeffrey Graetsch; Double Sided Chalk and Cork Board, Harvard University, c. 1950. 73 x 77 x 24.5 in. Sam Stewart, Ping-Pong Table, 2025. HPL, sapele 108 x 60 x 2.5 in. Photography by Sean Davidson.

Cory Arcangel, Three Stripes, 2018; inkjet on canvas. Triptych: 35.88 x 35.88 in. (each panel). Photography by Sean Davidson.

Al Freeman, Softer Dodgers Jersey, 2024; vintage Wool, wooden artists hanger. 52 x 48 x 5 in. Photography by Sean Davidson.

Background: John Roman Brown, Jerry, 2019; oil on canvas. 48 x 48 in. Middleground: Jean Prouvé, bed no. 17 for the Lycée Fabert, Metz Ateliers Jean Prouvé, France, 1935; enameled steel, upholstery, aluminum, rubber. Photography by Sean Davidson.

The pro shop created a strange temporal bubble within Weekend Tournament’s field of action. While the rest of the exhibition presented sports equipment as aesthetic objects removed from use, Muñoz’s corner preserves the ritual of maintenance and preparation. Here, function hasn't been aestheticized — it’s been ritualized. This is what remains when the athletes disappear but someone still believes in the possibility of their return.

By treating most sports equipment as sculpture, the show revealed hidden formal qualities we miss when we’re focused on function. Cory Arcangel’s Three Stripes (218) transforms the Adidas logo into pure abstraction. Will Gisel’s Bellwether (2024) incorporates artificial turf into minimal sculptural forms that suggest playing fields without defining specific games.

The curators understood that they were not just exhibiting objects; they were staging the afterlife of an idea. The Young Man’s Home believed that proper design could heal modernity’s mind-body split. Weekend Tournament operated from the assumption that this split has become permanent, maybe even productive. Instead of integration, we get aesthetic appreciation. Instead of use, we get contemplation. Instead of the gymnasium replacing the museum, we get the museum absorbing the gymnasium.

John Roman Brown, Ten Feet, 2025; oil on canvas. 120 x 72 inches. Photography by Sean Davidson.

This might sound like defeat, but Weekend Tournament made it feel like possibility. The show’s “field of action” doesn’t demand that we choose between physical and intellectual engagement — it created a space where both can coexist without the pressure to synthesize. You can appreciate the formal beauty of a medicine ball without feeling obligated to lift it. You can contemplate the engineering elegance of parallel bars without attempting a routine.

Walking through Weekend Tournament, you encountered the archaeology of Modernism’s most optimistic dream: that we could be whole people in spaces designed for wholeness. The exhibition preserved this dream while acknowledging its impossibility under current conditions. We can no longer imagine the gymnasium and the study as natural partners, but we can create gallery spaces where their artifacts converse across the decades, sharing stories about bodies and minds, effort and rest, play and work.

The intellectual athlete remains compelling precisely because the integration he represented now seems like science fiction. Weekend Tournament offered something different: not the promise of wholeness, but the pleasure of contemplating our beautiful fragmentation. It’s The Young Man’s Home for an age that’s given up on the young man’s earnestness but can’t quite abandon his dreams.

Chadwick Rantanen, Telescopic Pole [PreDrilled Tennis Balls/Neon Smiley], 2015; powder-coated aluminum, plastic, and walker balls. Dimensions variable. Photography by Sean Davidson.

Adam McEwen, Fountain, 2009; graphite. 18 x 16.6 x 13.25 in. Photography by Sean Davidson.

Detail of Sam Stewart, The Marty Cabinet, 2025; plywood, paint. 66 x 23.5 x 6 in. Photography by Sean Davidson.

Detail view of Weekend Tournament. Photography by Sean Davidson.

Exhibition view of Weekend Tournament photographed by Sean Davidson.