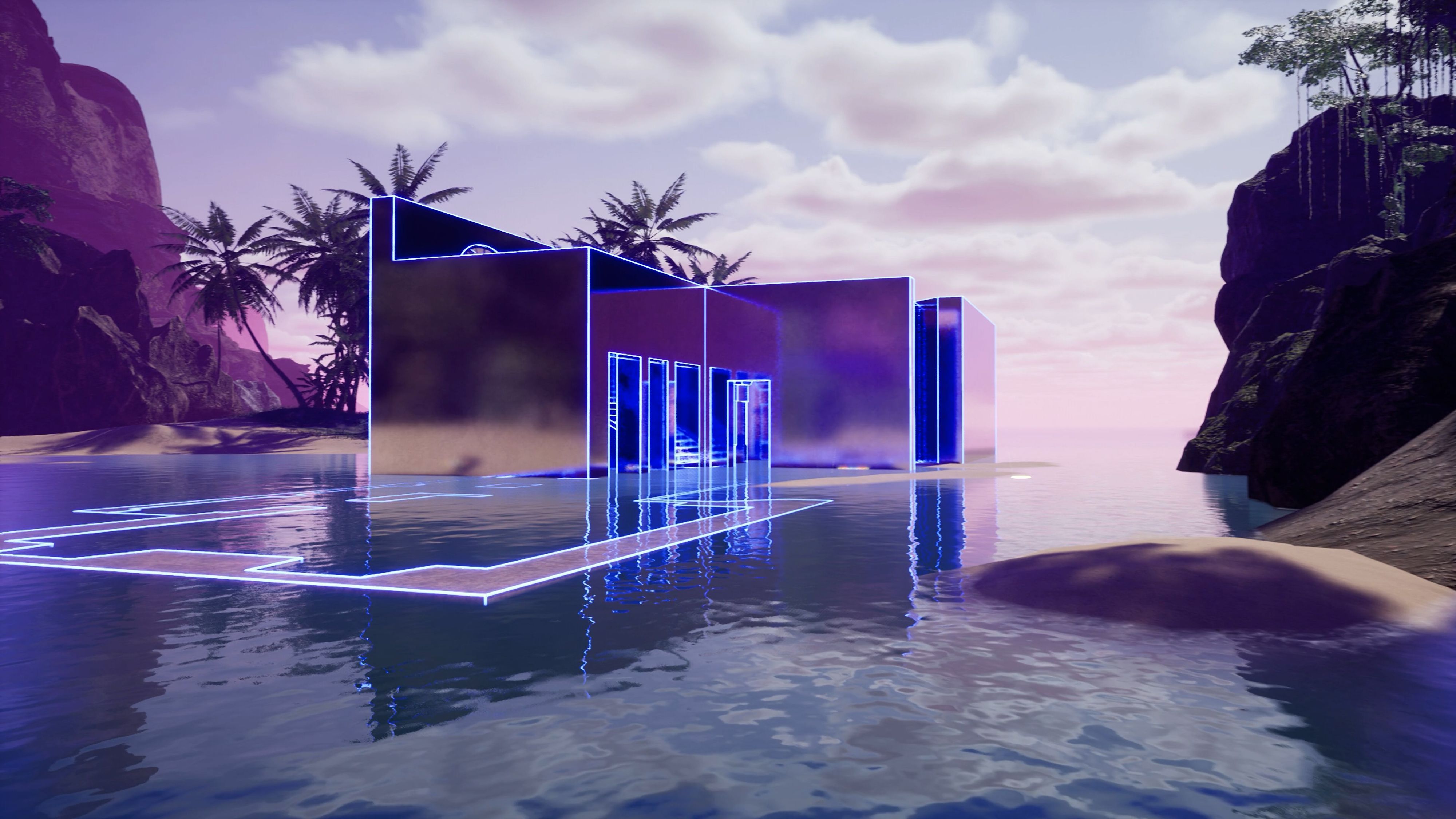

Theo Triantafyllidis, Ork Haus, 2022; Live Simulation, gaming PC, motion capture performance by Rachel Ho. Courtesy the artist and Meredith Rosen Gallery.

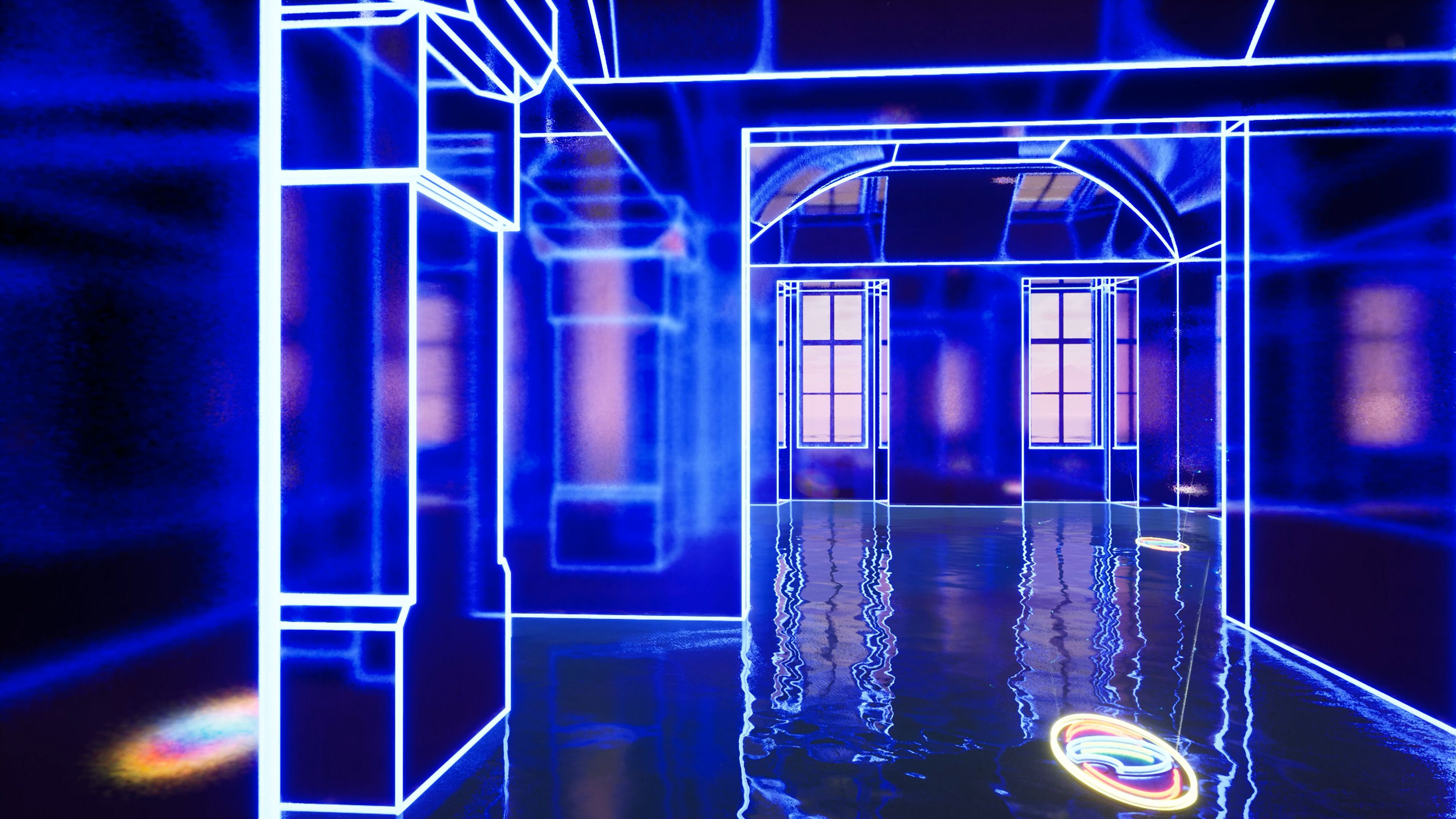

Lawrence Lek, Nepenthe Zone, 2021; Video game installation. Commissioned for the 2021 Ljubljana Biennale. Courtesy the artist and Sadie Coles HQ, London.

In her 2007 text Gamer Theory, McKenzie Wark made the claim that we are all gamers now: reality has been consumed by “gamespace,” as she termed it, so we can expect pure contest and agony for the rest of our lives. “Games are no longer a pastime, outside or alongside of life,” Wark argues. “They are now the very form of life, and death, and time itself. These games are no joke. When the screen flashes the legend ‘Game Over,’ you are either dead, or defeated, or at best out of quarters.” Updating Gamer Theory for the age of the Metaverse, the totalizing dystopia of gamespace and collapse of the “real” into the digital feels all-consuming, like there’s no way out. So what’s a poor little gamer to do?

Seize the means of production, of course, like any good Marxist — in other words, we must game-ify the game. The last decade has seen a considerable uptick of artists gravitating towards video games as an ideal medium to work through complex entanglements of the present in the speculative practice of worldbuilding, exploring the rich crossovers of architecture, technology, and ecology. The increasing accessibility of game engines like Unity and Unreal, as well as their ever-advancing rendering quality, facilitate the production of total environments, or unreal architectures, to prototype and critique many possible futures as they unfold in real time.

Lawrence Lek, Nepenthe Zone, 2021; Video game installation. Commissioned for the 2021 Ljubljana Biennale. Courtesy the artist and Sadie

Coles HQ, London.

These practices follow in the footsteps of Cao Fei’s landmark RMB City (2007–11). Fei built a fictional Chinese city in the online world of Second Life, which became a visual pastiche of Sino-futurist architecture and the flotsam of global capitalism — shipping containers, barbed wire, hardhats, and AstroTurf. After RMB City was opened to the public in 2009, the online RMB community developed organically in a mostly deregulated environment, with its “citizens,” or players, participating in town hall meetings. It proved the power of speculative fiction and simulated architecture to reflect on real-world issues of political organization, urban development, and cultural expression.

Fifteen years later, we’re facing the advent of the Metaverse — like every technological frontier, its utopian promise is a fantasy narrative that attempts to conceal the vast inequalities and social siloing that virtual reality will exacerbate, not dissolve. The Greek-born, L.A.-based architect-turned-artist Theo Triantafyllidis explores this truism in Ork Haus (2022), a live simulation piece that runs on a similar set of algorithms to those powering The Sims. The tech-obsessed Shrek look-a-likes and various other animal associates, including a turtle riding a Roomba, remain glued to their screens in unstable domestic bliss as the world burns outside (and inside — a kitchen pan catches fire but no one seems to notice). Stuck inside a simulation of their own invention, the Orks remain isolated and powerless against multiple ends of the world — coalescing online and AFK (away-from-keyboard).

Theo Triantafyllidis, Ork Haus, 2022; Live Simulation, gaming PC, motion capture performance by Rachel Ho. Courtesy the artist and Meredith Rosen Gallery.

Conversely, Triantafyllidis’s Pastoral (2019), with its bucolic architectural installation featuring hay bales and golden-hour light, is a glimpse of the simulated sublime. Released as a free game file, the work features a buff she-Ork contemplating the beauty of life through a sunset in an ever-expanding field. As the light ripples off the Ork’s muscular frame, her neon ponytail dancing in the wind, a lute melody plays in the background. Viewers can download the piece and open it on their PCs whenever they want to drop into this paragon of rustic Zen.

The stakes are raised considerably in Berlin/London-based artist Danielle Brathwaite-Shirley’s latest project, SHE KEEPS ME DAMN ALIVE (2021), recently presented at arebyte Gallery in London. In a powerful subversion of the shooter game, visitors to the exhibition are instructed to pick up a custom-molded weapon, pink and fleshy like a brain, and begin their quest to protect Black trans lives. Across three simulated game spaces — the Ocean, the Dungeon, and the City — players must shoot and hold fire strategically, without being told who is the enemy and who must be guarded. Four cameras installed around the gallery globally broadcast the experience live via Twitch, while Brathwaite-Shirley, who narrates the game, points out the player’s inevitable failures, heightening the experience of extreme discomfort. The question of individual agency, a crushing feeling of surveillance, and the audience’s forced accountability in recognizing their failure to protect trans lives while acknowledging the damage of their performative ally-ship makes Brathwaite-Shirley’s work an icon of what the artist terms “active art,” and one of the most important gamespace projects of our time.

Theo Triantafyllidis, Ork Haus, 2022; Live Simulation, gaming PC, motion capture performance by Rachel Ho. Courtesy the artist and Meredith Rosen Gallery.

Theo Triantafyllidis, Ork Haus, 2022; Live Simulation, gaming PC, motion capture performance by Rachel Ho. Courtesy the artist and Meredith Rosen Gallery.

London-based architect-turned-artist-and-musician Lawrence Lek’s Sinofuturism trilogy (2016–19) is another major gamespace project that weaves together many complex themes: the question of creativity and agency in A.I. systems, the future of China and its relationship to automated technologies, the hazy border between humans and nature, and the extreme corporatization of the future. Lek’s ultra-immersive, feature-length films blur the boundaries between music video, video game, and video art as characters and chronologies move fluidly across the series and expand in hazy spatial-temporal parameters, like an ultra-H.D. mobius strip. The first of the series, 2016’s Sinofuturism (1839–2046 AD), takes seven key stereotypes of Chinese society — computing, copying, gaming, studying, addiction, labor, and gambling — to show how the country’s technological development can be understood as a form of artificial intelligence. The second, Geomancer (2017), features an A.I.-powered weather satellite that descends to Earth to actualize its dreams of becoming a pop star, while in AIDOL (2019), the final installment, the satellite Geo and the waning pop star Diva team up on Diva’s attempted return to the limelight. For her comeback, Diva chooses the half-time performance at the 2065 eSports Olympics, where humans and A.I. gamers battle in a snowed-out jungle world.

Theo Triantafyllidis, Smoke Break, 2018; HD projection, 4:33 min. Courtesy of the artist and Meredith Rosen Gallery.

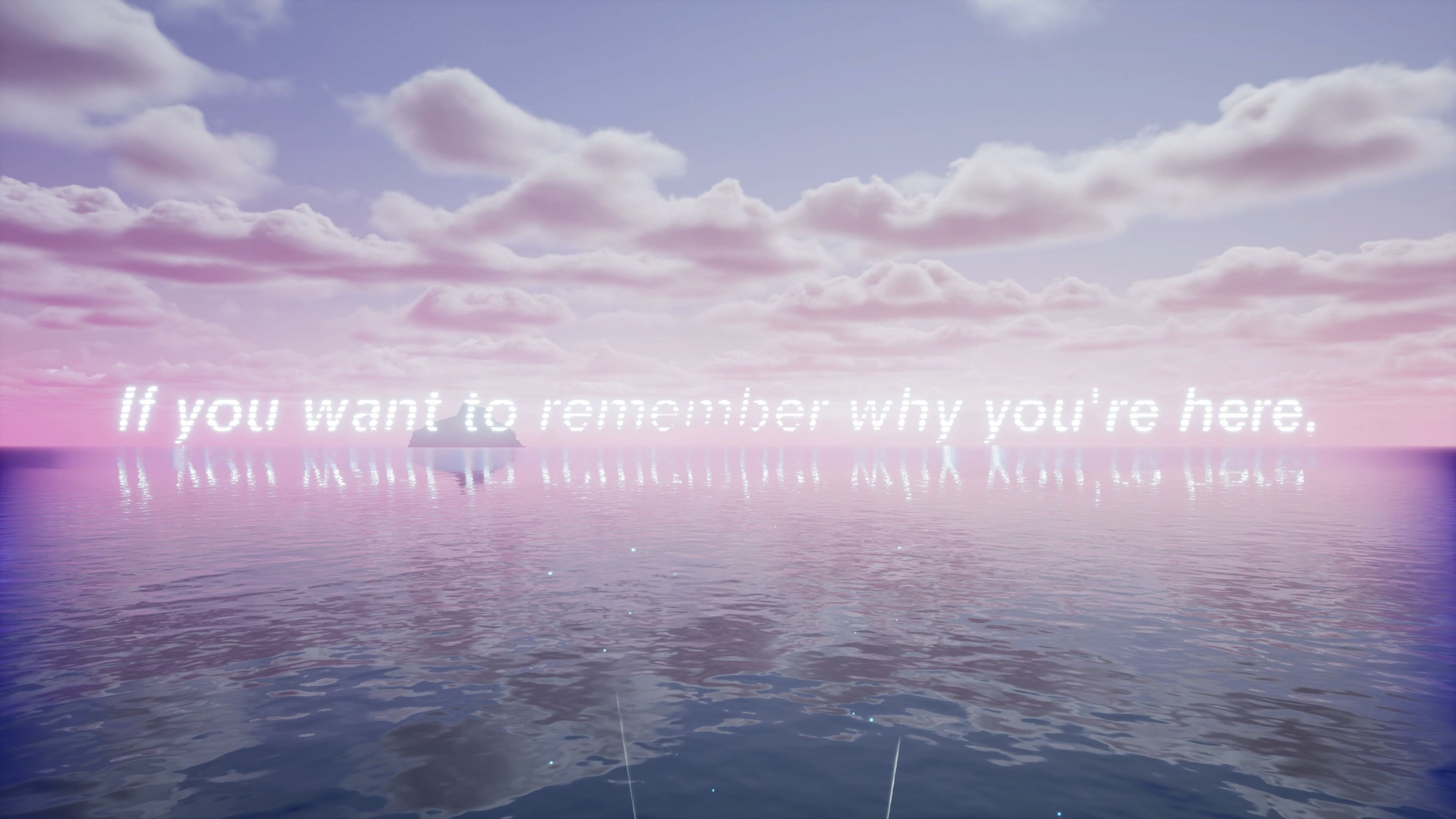

In Lek’s most recent piece, Nepenthe Valley (2022), he takes an important step back from the narrative maximalism of his Sinofuturism trilogy to create an ambient sonic world that addresses the impact of virtual space on our mental state. Devised as a series of interactive open-world games, the playable environment adapts to the site where it is shown, utilizing a custom soundtrack, a loose script of instructional texts, and glossy, neon-soaked architecture to conjure a trance-like environment. Understanding the game space as a new kind of spa or temple, Nepenthe Valley has no clear beginning or end, no comprehensible architectural order. Instead, viewers float hazily from one room to another, echoing the psychological phenomenon where, upon entering a room, you forget the reason for being there in the first place. Nepenthe Valley toys with memory, healing, and the dream-like state produced by this unreal architecture, suggesting its capacity to influence and expand our relationship with the “real” world we inhabit.

Lawrence Lek, Nepenthe Zone, 2021; Video game installation. Commissioned for the 2021 Ljubljana Biennale. Courtesy the artist and Sadie Coles HQ, London.

As the technical capabilities of real-time computer graphics and the immersive qualities of game-engine design continue to evolve, gamespace becomes an increasingly salient environment for reflecting on the complex entanglements of politics, ecology, technology, and identity that underscore the present. These unreal architectures are a powerful and precious medium to imagine, prototype, and give language and agency to a dizzying array of possible futures we may or may not like to inhabit. As gamers locked into what often feels like a slow apocalypse where we don’t know the rules, the rich symbolism of game engines and the visionary worlds woven by these artists offer an exhilarating space for speculation that steers clear of Metaverse apathy, instead remaining rooted in the realm of the collective real.