SUBURBAN CODEBREAKER

by Joseph MagliaroThe non-conformist landscape architect James Rose and his fight against the codes of suburban New Jersey.

The landscape architect James C. Rose (1913–91) photographed in 1944, holding a model of what would later become his home in Ridgewood, New Jersey. © James C. Rose Archives, courtesy James Rose Center.

Design is often conceived as an efficient, complete solution to a series of given limitations such as budget, time, space, material, code, and law. But this is not inevitable. Design can also be approached as an open form, an ongoing process in which provisional assemblages actualize specific modes of engagement without ever resolving or completing a program: smartphone apps and OS updates offer ready examples of this kind of iterative approach to design and its capacity to release or stifle emergent modes of behavior by tweaking the norms of an interface. Those who approach design in this manner are rarely content to plug a solution into a hole markedout by a set of existing conditions; rather, they tend to see the designed environment as a field of latent possibilities that, when given attention, point to new ways of answeringthe question “How might we live?” This is precisely the question James Clarence Rose (1913–91) sought to address through a lifetime of interventions in the landscape of suburban America. Until recently, his legacy — a significant body of writing on landscape design, as well as numerous built “sculptures in the landscape” — was only known to historians in the field. Thanks to the ongoing work of the James Rose Center for Landscape Architectural Research and Design and the recent recognition of his former New Jersey residence by the National Register of Historic Places, this circle is now growing.

In his search for answers to how we might live, Rose was not a man to humor petty bureaucrats or arbitrary codes that sought to constrain the lifestyles he wished to explore — be that dropping acid with Timothy Leary, disavowing the aesthetic and social constructs of the post-war suburb, or living openly as a gay man. For Rose, an existing law or tradition was not to be viewed as part of a natural order or beneficent “limitation” that Walter Gropius claimed “obviously makes the creative mind inventive.” As he wrote in the last of his four books, The Heavenly Environment (1987), “There has never been a scarcity of limitations. The real question is whether they are limitations imposed by nature or obstacles imposed by man.” Throughout his career, a code or limitation was not something to be revered, but an obstacle to be overcome, “a rusty gate that should never have been put there in the first place.”

This penchant for questioning received codes of conduct began early. Born in rural Pennsylvania, Rose grew up in New York City, but did not graduate from high school because he refused to take music and mechanical drafting. He nonetheless convinced Cornell University to admit him to its architecture faculty, which he attended for several years before transferring to Harvard to study landscape architecture. With fellow students Dan Kiley and Garrett Eckbo, Rose began to explore the potential for a landscape architecture that did not see interior and exterior space, or natural and built features as separate concerns, but rather as integrated aspects of a designed environment. The faculty, hewing to more traditional, Beaux-Arts methods, did not condone this approach, and in 1937 Rose was dropped from the program for refusing to fall into line. The following year was one of transition at Harvard, the landscape-design department emerging as a branch of the Graduate School of Design under recent émigré Walter Gropius, who proved more sympathetic to Kiley, Eckbo, and Rose’s avant-garde tendencies. In 1938–39, after Rose’s readmission, the trio published a series of essays that articulated key thematics of a nascent modern approach to landscape design: reduction of ornament, rejection of axial systems of composition and of rigid adherence to geometric form, responsiveness to the contemporary needs of those living within a particular landscape, appreciation for the inherent character of materials, and, most importantly for Rose, an understanding of the entire site — interior and exterior, built and natural, human and nonhuman — as an integrated process of living with, rather than as a mere machine for living in.

View of the entrance courtyard of James Rose’s former home, which now houses the James Rose Center. The wood-clad structure stood out like a sore thumb in the eyes of his neighbors in conservative Ridgewood, New Jersey. Instead of opting for a classic picket-fence suburban home, Rose’s idea for the corner property was to develop the steeply sloping site into a series of terraces, tethered to existing trees and stitched together through a system of steps and paths. The largest of these terraces would include the house and would be “simply another level in the remade landscape.” Photograph by Frederick Charles, taken in 1996. Courtesy FCharles Photography.

Once again, Rose would not complete his studies, leaving Harvard without a degree. After a brief sojourn in California, he returned to New York, where he began working for Antonin Raymond as lead designer of the staging facilities for the Sixth Air-Defense Artillery Regiment at New Jersey’s Camp Kilmer. In 1943, after being drafted into the navy, he found himself stationed in Okinawa: it was there that he began to plan a project that would come to serve as a manifesto, a studio, and a family home — although ten years would pass before it was finally realized.

On his return to New York after the war, Rose built a successful practice on the Lower East Side, teaching at Columbia and Cooper Union and seeing his work and writing regularly published. All the while, he searched for a location upon which to build the home he had envisioned while in Okinawa. As he explained in The Heavenly Environment, the house would not dominate its context, but would be one of several components that contributed to the interplay he saw as “neither landscape, nor architecture, but both; neither indoors, nor outdoors, but both.” In the mid-1940s he published drawings for his planned residence along with an essay that prefigured the Japanese Metabolists’ use of biological metaphors for systems in which indeterminacy allows for complex, diverse structures to emerge. Rose’s plan called for the use of a geometric grid to establish an armature within which a series of shelters, interconnecting paths, outdoor “rooms,” and gardens would be deployed. All of these were to remain open to adaptation, allowing the ensemble, as he explained in an October 1946 article in American Home, “to grow, to mature, and to renew itself as allliving things do.” This process of “metamorphosis,” as he described it, was part of his belief that the design of a landscape is never complete: “finish,” he wrote in The Heavenly Environment, “is another word for death.”

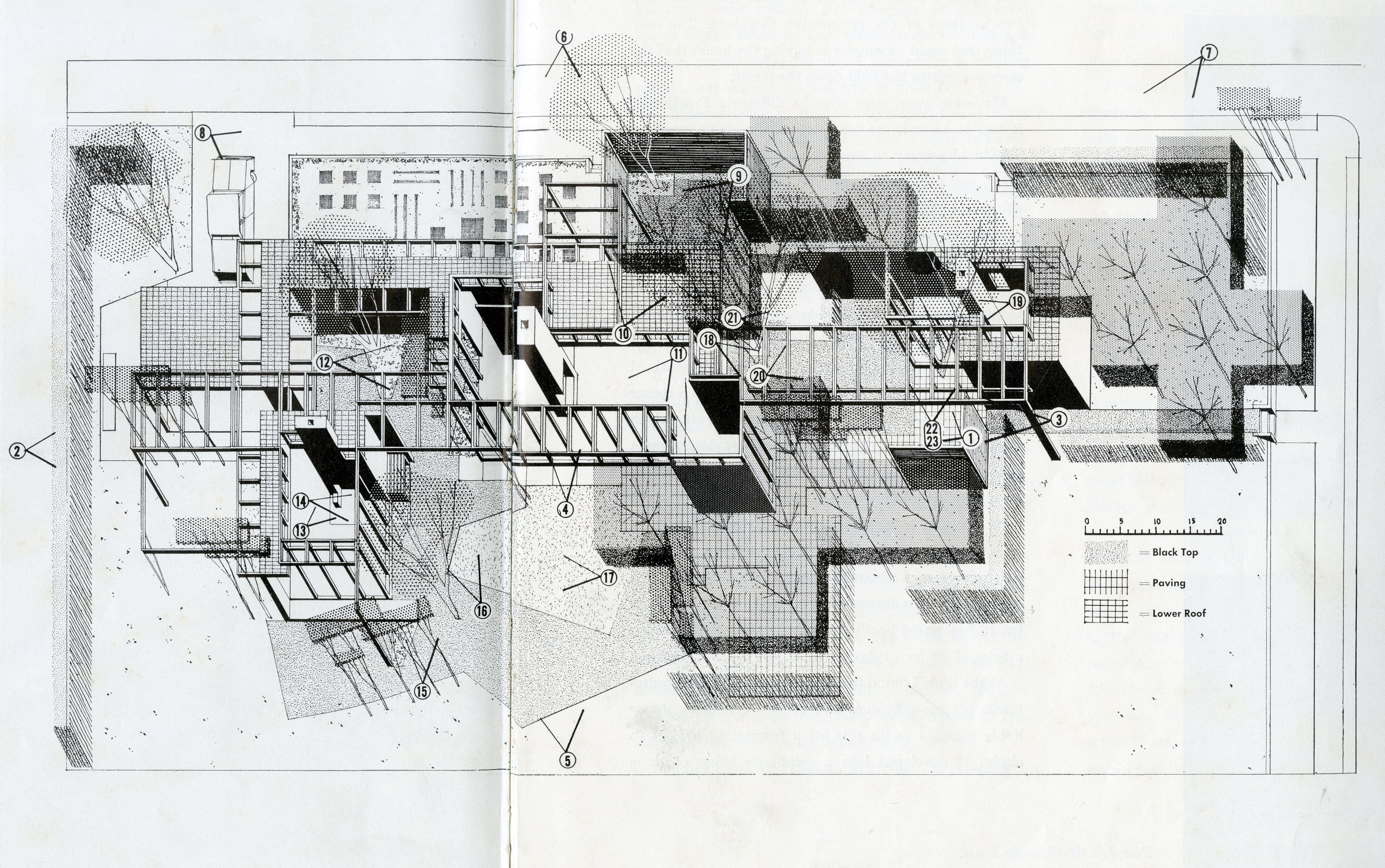

Axonometric plan of James Rose’s home, which he continuously worked on between 1958 until his death in 1991. Drawing by Charles Rieger from the book Creative Gardens, published in 1958. Courtesy James Rose Center.

In 1952 Rose finally secured a small, irregular plot of land in Ridgewood, New Jersey — a town he soon dubbed “Sunkenberg” in reference to his incipient antagonist, a local building inspector of the same name. In compliance with local setback codes, his plan called for the shelter components of the project to be limited to an area half the size of a tennis court, within which he proposed three independent structures—a studio for himself, a living space with a kitchen for his mother, and a separate living area for his sister—all interconnected by open courts and gardens that spanned the entire area of the site. He designed furniture to be used indiscriminately both inside and out, contributing to the sense of “throughness” or indistinction he sought to achieve. Rose’s initial plan was to build in timber, like neighboring homes, but after a meeting with “the city fathers of Sunkenberg,” including the building inspector and the mayor, Rose was informed that his “avant-garde” design would not be welcomed in Ridgewood, and that any local architect who attempted to facilitate his approval process would likely never receive another commission in the area.

Inspired by Zen architecture, James Rose sought to achieve indistinction between inside and outside, creating a seamless transition between providing shelter and living with the environment. Photograph of James Rose’s former home by Frederick Charles, taken in 1996. Courtesy FCharles Photography.

In The Heavenly Environment, Rose describes this episode in detail, and it is worth recounting since it captures the kind of experience that both sharpened his thinking onthe social potential of design and pressed him to articulate a method for overcoming the arbitrary obstacles that stand in the designer’s way. After demanding a hearing with the Ridgewood building inspector, he was told his plan had been rejected because the area was zoned for masonry rather than timber construction. The fact that every house within view of Rose’s property was in timber failed to compel the inspector, who insisted that the code had recently been modified. When Rose inquired whether that was truly the reason his plan was rejected, the inspector replied, “Of course ... we’d like to have a nice stone house on that location.”(He would later reveal that he had fabricated this transformation of the law in order to deter Rose from building on his land. Why, one wonders, would he — in the name of a “we” — do this? Was it out of concern for propriety, or a distaste for the unconventional that he denied the plans of a credentialed landscape architect and educator? Or could it be that this “we” sought to impose limitson a man whose “avant-garde” tendencies were not limited to his aesthetics, but also included his sexuality? Rose does not mention this in his writing, but one wonders whether the city fathers had been talking...)

After gaining assurance that the use of masonry would satisfy all conditions preventing his plan from receiving approval, Rose prepared new drawings for an essentially identical structure composed of concrete block, wood framing, and floor-to-ceiling glass walls. Displeased with the modification and Rose’s interpretation of the request for “stone,” but unable to present a legitimate reason for disallowing the proposal, the inspector granted the permit, and construction began. Additional challenges surfaced throughout construction — code limiting the height of a wall not attached to a roof, for example — but Rose followed his growing conviction that overcoming the rusty gate of convention requires a paradoxical investment: one must “at times [use] devices within the rules to violate the rules.” If code would not allow for a 6-foot-high wall to screen his property from the noise of the street and the eyes of neighbors, he would demonstrate the arbitrary nature of this code by constructing a 2-foot-high earth retaining wall (allowed by code), upon which he would build a 4-foot-high wooden fence (also allowed by code). Over the course of his career, Rose would again and again exploit the loopholes unwittingly left by building legislators to expand the possibilities of suburban form.

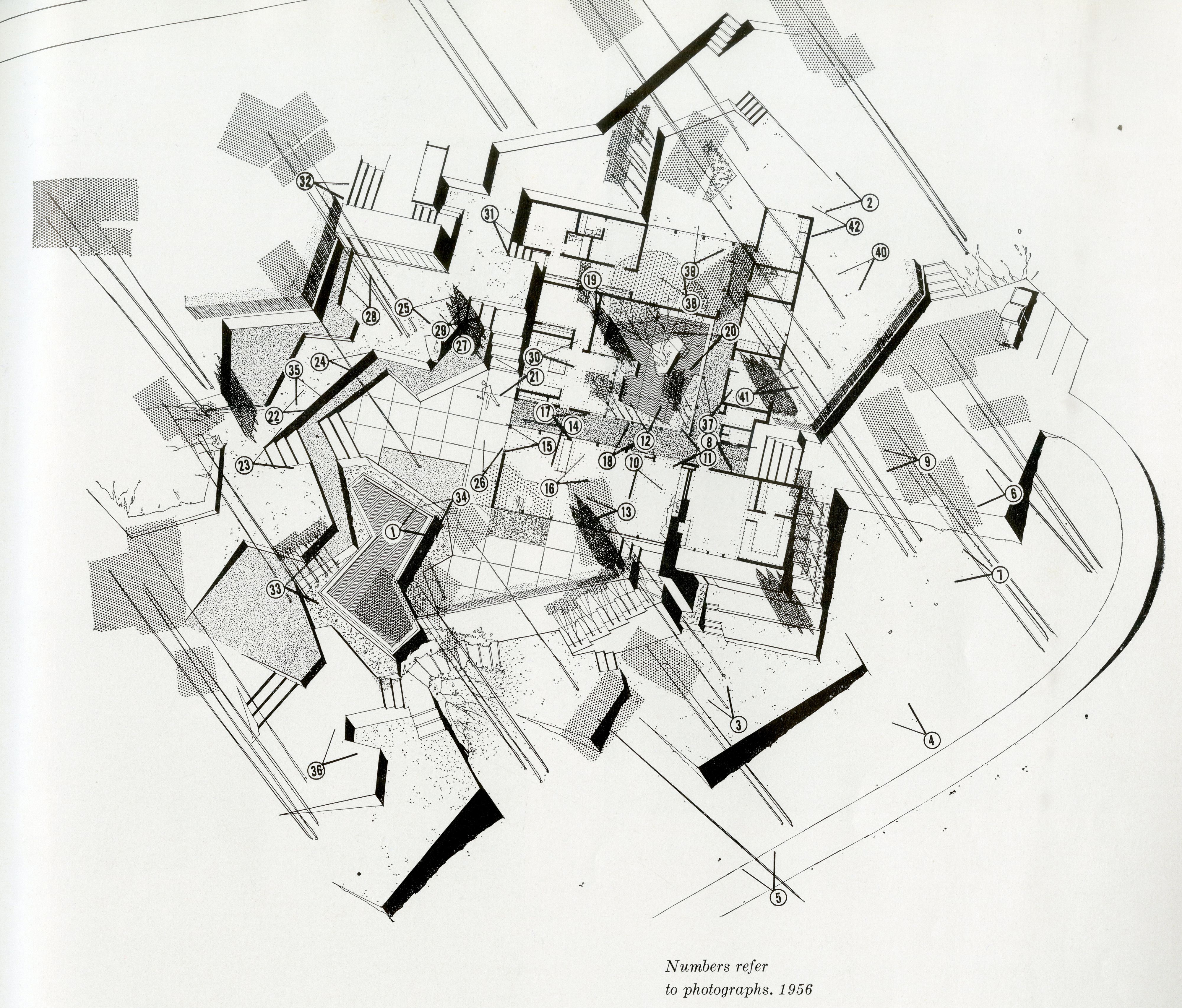

Rose’s plan for the landscape of the Zheutlin environment (1956) was a work of art in and of itself. Taken from Rose’s book Creative Gardens, published in 1958. Courtesy James Rose Center.

Though he moved into his Ridgewood residence in 1953, that date did not mark the completion of the project but rather its beginning. His home became the laboratory for his idea of “metamorphosis” right up until his 1991 death from cancer. These experiments included many subtle alterations, as well as two significant changes. The first came in 1968, when he enclosed a large portion of the open-air “rooms” to produce more distinct and independent living quarters by adding kitchens to the north and south dwellings. The result was a denser sheltered environment, which somewhat diminished the interplay between interior and exterior zones. This trajectory is similar to that followed by Kiyonori Kikutake’s 1958 Sky House, which Rose likely encountered whileattending the 1960 Tokyo World Design Conference, at which the Metabolist manifestowas first delivered. Following the conference and a period of travel, Rose became committed to Zen Buddhism, and to near-annual visits to Japan — both of which influenced the form of his home and his working methodology. In the early 1970s Rose added a zendō and a trellised roof garden to the Ridgewood ensemble, and many of his subsequent commissions were informed by his Zen practice: after meditating in the morning, he would head to the project site and work extemporaneously with the conditions at hand rather than with a predetermined plan.

This approach to landscape design as a process of ongoing metamorphosis offered an engaging alternative to the banality of suburban form, but it also served as a pointed critique of mid-20th century suburban ideology. The impediments Rose faced while realizing his Ridgewood home crystalized into a guiding conviction that the laws governing our lives and environments had been imposed arbitrarily, and it is therefore the duty of the designer to expose this contingency and expand the realm of discourse and material practice deemed acceptable by social convention. If the suburbs were washed by conformity, then, Rose recognized, they might also provide a surface on which to inscribe a practice committed to change. In the process of building his Ridgewood home, Rose moved his base of operations to New Jersey, abandoning his New York studio and team. Over the next 40 years, he operated a design/build practice focused almost exclusively on producing landscapes that disrupt the conventions of the suburban home.

Rose made a choice that was perhaps less one of practice and more one of praxis. If there is a through-line across the five decades of his career, it is this: he used landscape design to point to places where existent customs function to exclude some possibilities in favor of others, often without good reason, or for the benefit of those in power. For Rose, direct engagement with the built environment could not but result in acts of civil disobedience. When confronted with “socially approved mind-fixes” that prevent a person or a landscape from “fulfilling its potential, it is quite necessary to break some of those ‘laws’ ... in the sense that Henry David Thoreau recommended,” he declared in The Heavenly Environment. By calling for a practice of civil disobedience in the landscape — using the rules to violate the rules — Rose invites us to follow his example, offering a strategy for confronting established codes in order to make space for non-normative forms of life today.