AN ILLUSTRATED ODE TO THE ARCHITECT’S DOODLE

While the contemporary artist is hardly expected to know how to draw, but rather to have mastered the art of coordinating on the phone, there is still a persistent belief in the demiurgic ability of the hand of the architect. Practically all architects insist on this: the most elaborate software will never replace an end-of-lunch scribble on a torn-off piece of coffee-stained napkin.

Would a mile-high skyscraper, or a gravity-defying cantilevered structure, command the same public admiration if they were simply the product of computer calculations? We’re all told that prior to the insane math and technical prowess, there was a sloppy drawing. The more rudimentary the sketch, the more vertiginous the gap between the creative act and its realization. Can you imagine, from your business suite on the 108th floor, that your tower was first drafted on an Emirates airline menu after a second cognac halfway through a long-distance flight? Or from the walkway in your art museum, where a Richard Serra looks like a mere scrap of metal under the gigantic glass dome, that its audacious forms were roughly scribbled on a sticky note minutes before the first design meeting?

With fewer people smoking nowadays, it’s unlikely that a significant project will be sketched on the back of a matchbook, but for the architect on the go, five-star-hotel stationery or bar coasters offer a perfect foundation for the Promethean doodle. Why not, you may ask, sketch your next museum project on an iPad or in your Moleskine with a fountain pen? This would lack mystery. The great architectural sketch is a fragment, a piece of archaeology, a spurt of genius dashed down on whatever found material happened to be at hand at that crucial instant.

Some architects, true-born sculptors, spontaneously think in three dimensions and, seated on a bar stool, make an impromptu scale-model out of nothing. Toothpicks, chunks of bread, sugar cubes, or, even better — “Excuse me, do you have cigarettes?” — after which, to the surprise of the bartender, the great architect empties out the packet and starts folding the foil lining. An iPhone snapshot of the silver-and-white origami is immediately emailed to the discerning magnate commissioning the project: “Here is your art museum”!

It must be torture, to CEOs, shareholders, and their various advisers, to watch the lengthy presentation of projects submitted for a competition. But what if, instead of soulless, hyperrealist renderings which give you the sense that you’ve already moved into your new headquarters, or that your supposedly stunning flagship has been digested by the press before it’s even been built, architects sent you their original scribbles and preliminary scale models? Wouldn’t that be more entertaining? — a true collection of Art Brut, which could be contained in one suitcase like a Marcel Duchamp portable museum.

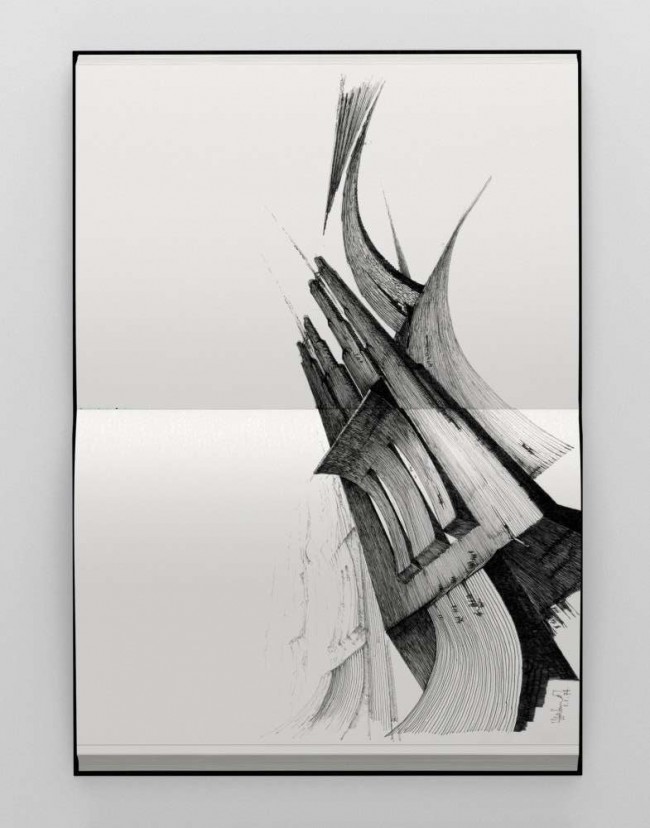

However, it would be unfair not to point out that some architects would never deign to indulge in rudimentary doodles, for lurking in many a master builder is an artist manqué. With them, when inspiration blows in, it’s like a tornado engulfed by a Christo and Jeanne-Claude wrapping. The sketch takes on the dimension of a gigantic canvas, with washes of emerald and drips of pink that suddenly make the stern housing project seem like it’s emerging from a Peter Doig masterpiece, a supplement of dreams for the price of regular plumbing and electricity. Collage is also a favored technique among crafty architects who want to unleash creativity from the very outset of the project. Beyond the childlike playfulness of the paper cut-outs, there’s a deeper reflection on the political and social issues at work in any built structure. Isn’t architecture itself a form of juxtaposition? There’s a message in the architect’s collage: instead of alienating the future owners with the constraints of a totalitarian aesthetic, it anticipates the customization of the building by its inhabitants. Added balconies, windows, doors, verandas, contrary to being banned, will be encouraged to compose a Surrealist cadavre exquis, prolonging the free spirit of the original design.

Alas, this genuine material, this rare and precious concentration of ideas, only usually surfaces once the building has been completed. (It’s even suspected that some architects do their sketches afterwards, to bring a touch of human quality to a finished project.) But when the time comes for a retrospective, the sketches are carefully taken out of drawers to be included in a coffee-table monograph. Fingerprints and scribbled memos of errands are welcomed on these graphic relics as a refreshing counterpart to the alienating slickness of glossy building photographs or the dry precision of line-drawn plans. Or they might be exhibited under armored glass in the hallway, so visitors can bend over to stare in awe at the ballpoint pen child-drawings of a tower, scribbled on a 3,500-dollar Four Seasons lunch bill. “So, it’s only that!” marvel the visitors before they enter the elevators.

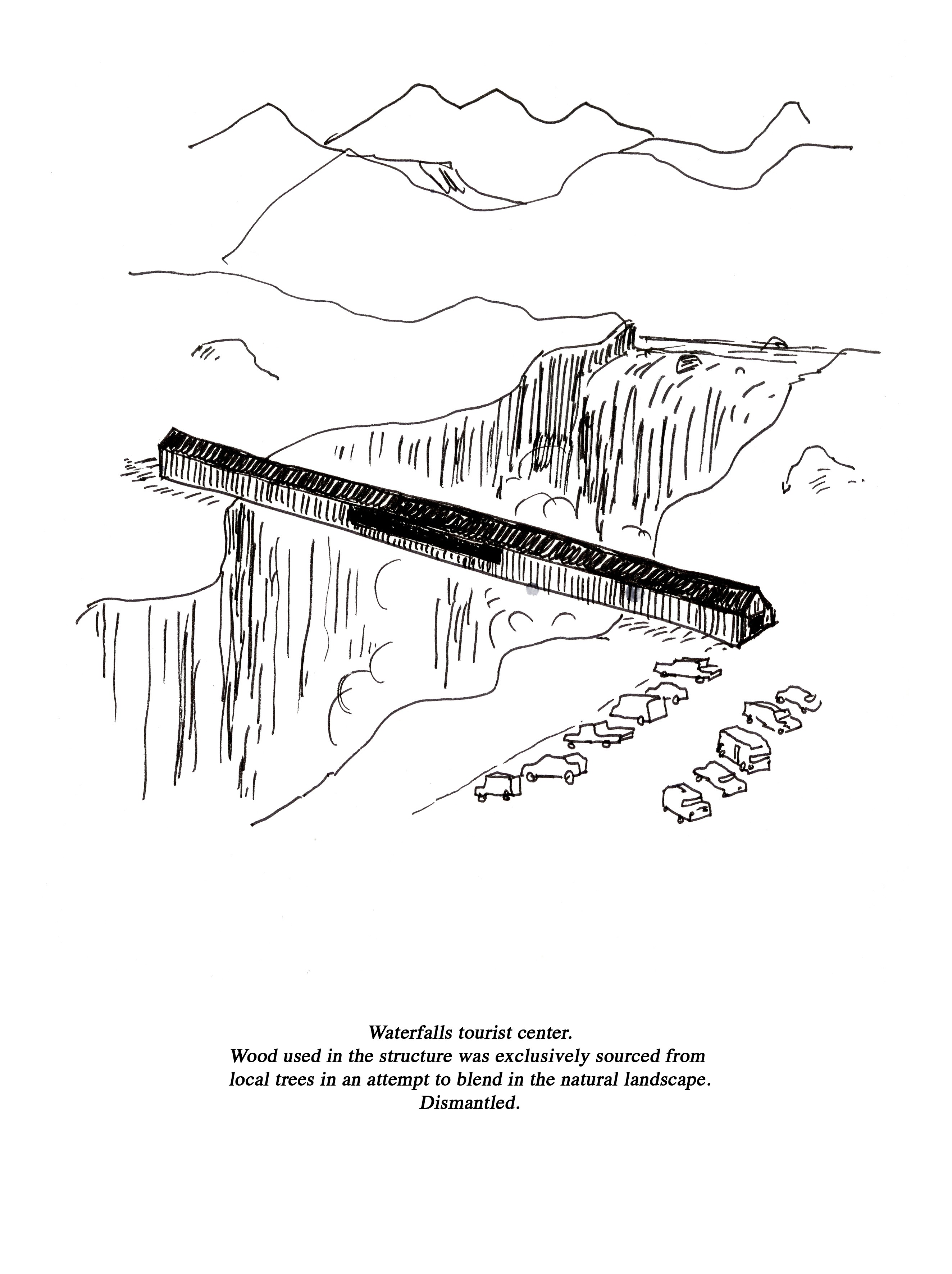

But these are just the products of the superfluous narcissist, the architect of the public imagination. All this decorum is of no account for the practitioner. The real architect’s sketch is about finding a solution — with supporting evidence, especially when the proposition is disputable. It is not for the architect to debate whether the world needs another art museum, or a ski resort in the desert, but rather through his or her project to suggest a general sense of improvement: be it a jail or a tourist center, it should be a step forward. Regardless of the function of the potential building, an architect’s sketch should have the intimidating power of a New Zealand-sheep-barn-turned-summer residence on Instagram, the prerequisite Donald Judd box.

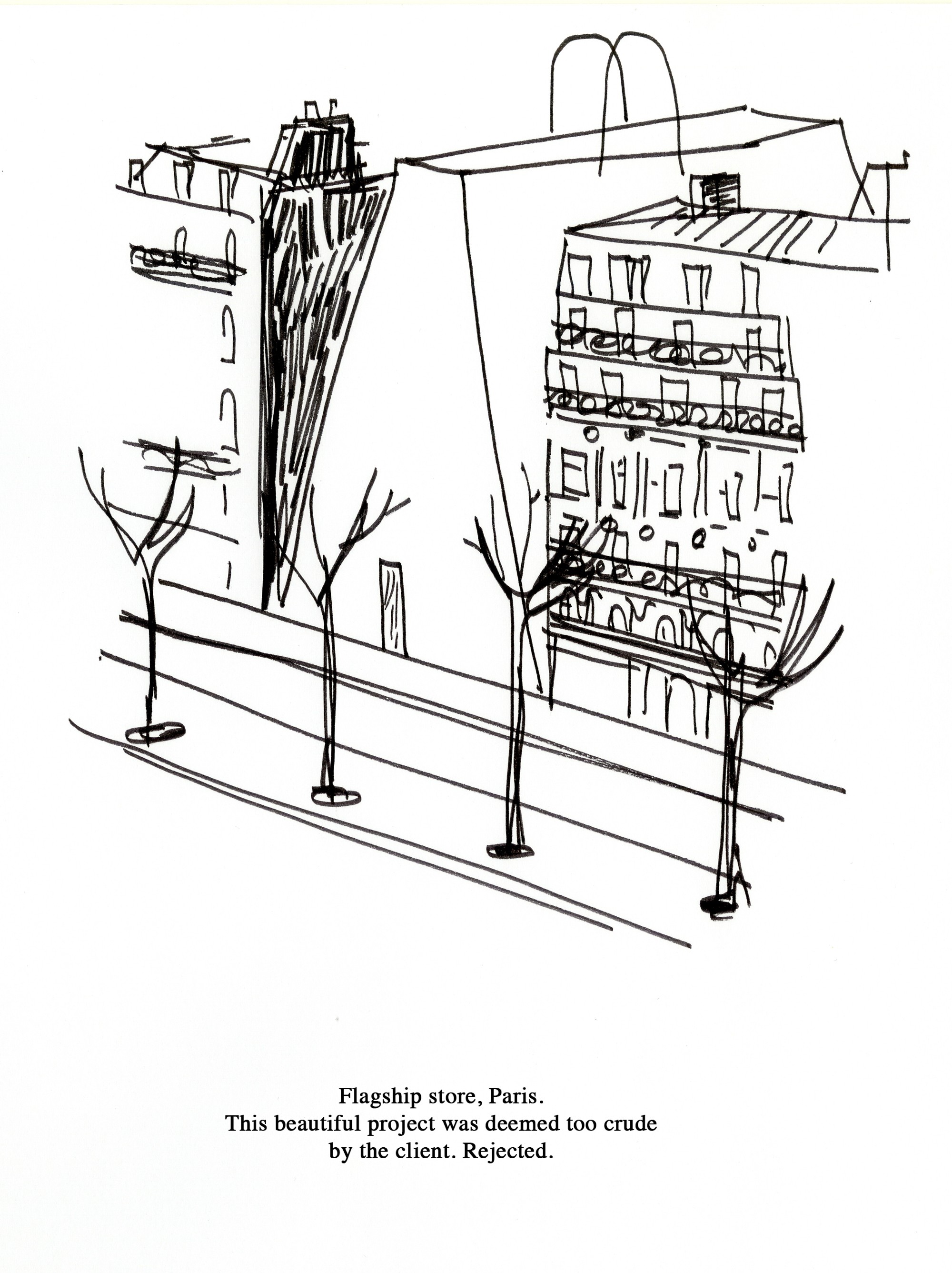

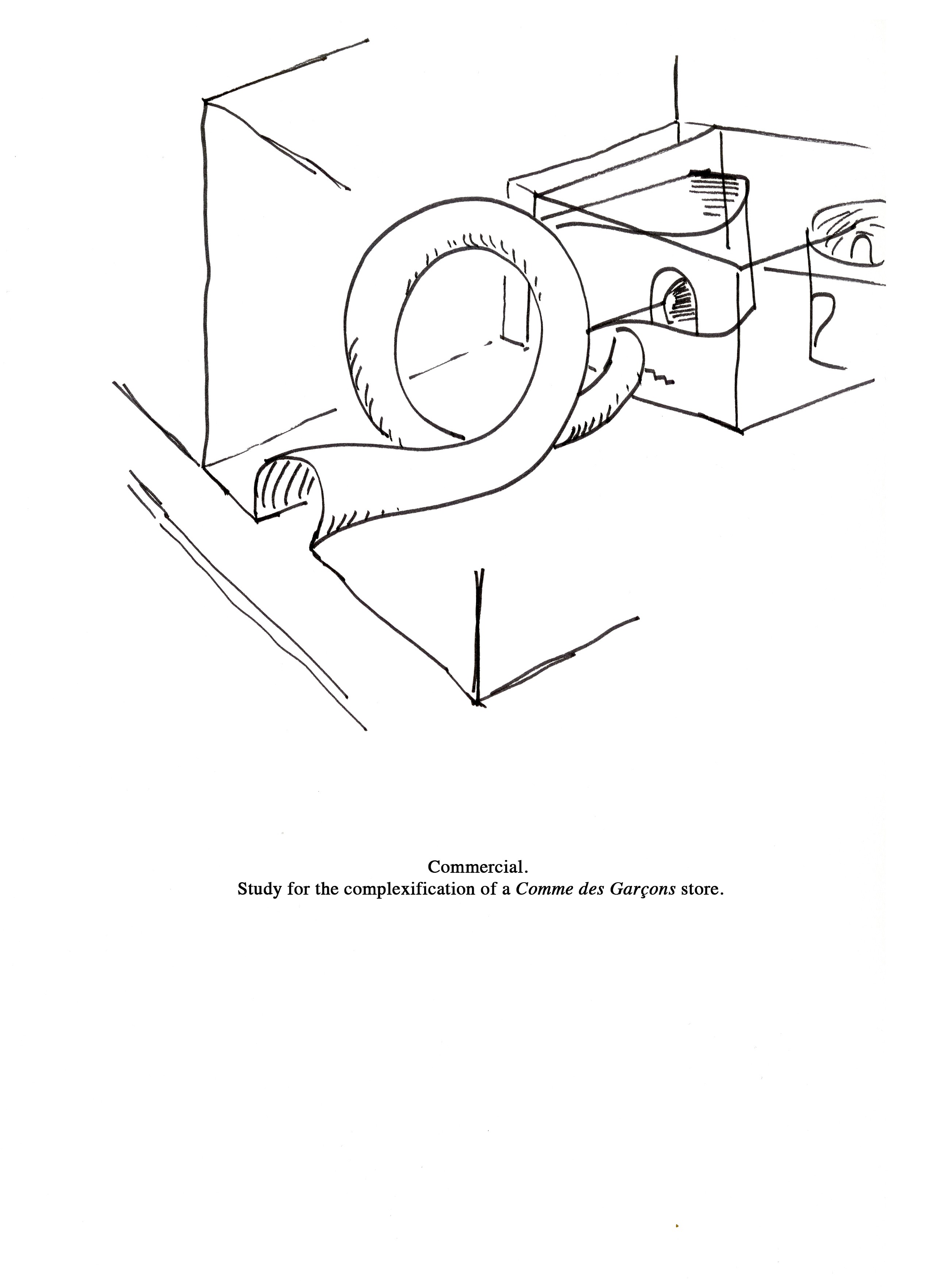

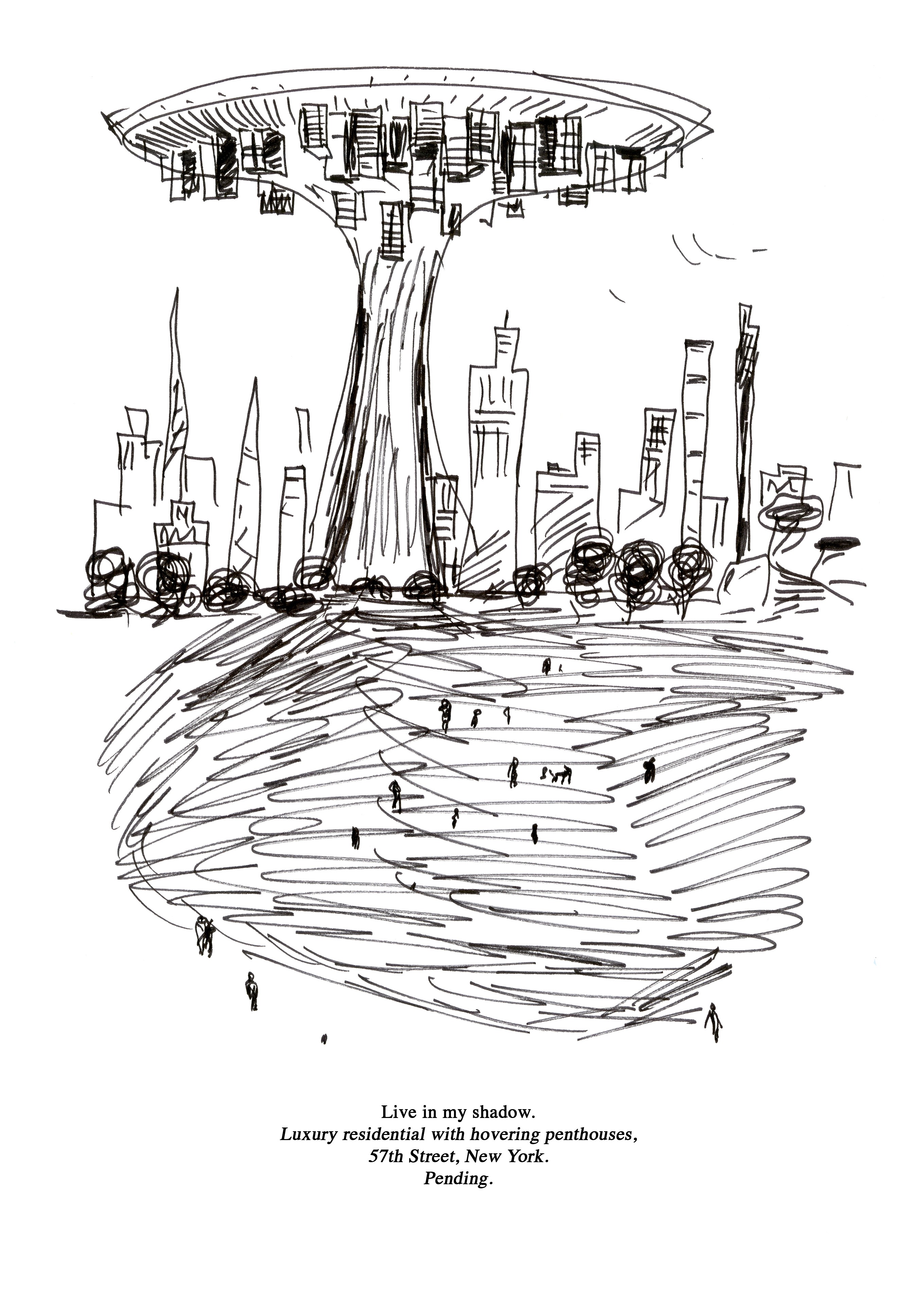

A moral stance is mandatory: a fashion boutique should challenge the public in the same way an art installation does; a trucking hub should be an interesting addition to the landscape; a billionaire’s private residence should be self-sufficient. Our suffocating culture of social media often gives us the sense of everything having already been done. By the time a new spa is drafted, similar structures are already in the blogs. Contemporary-art museums multiply like a new kind of Starbucks. The luxury industry has already placed its spectacular flagships everywhere, and residential skyscrapers are in a constant war to overshadow one another.

This leaves the field open for the very small, the mega-modest, the almost invisible. In the end, the most valuable projects may be the ones that are never built — bold ideas turned down by a client’s cowardliness, solutions unfairly rejected, projects ahead of their time, visions deemed too utopian. These are the real jewels of the architect’s drawer.

Artwork and text by Jean-Philippe Delhomme.

Taken from PIN–UP No. 21, Fall Winter 2016/17.