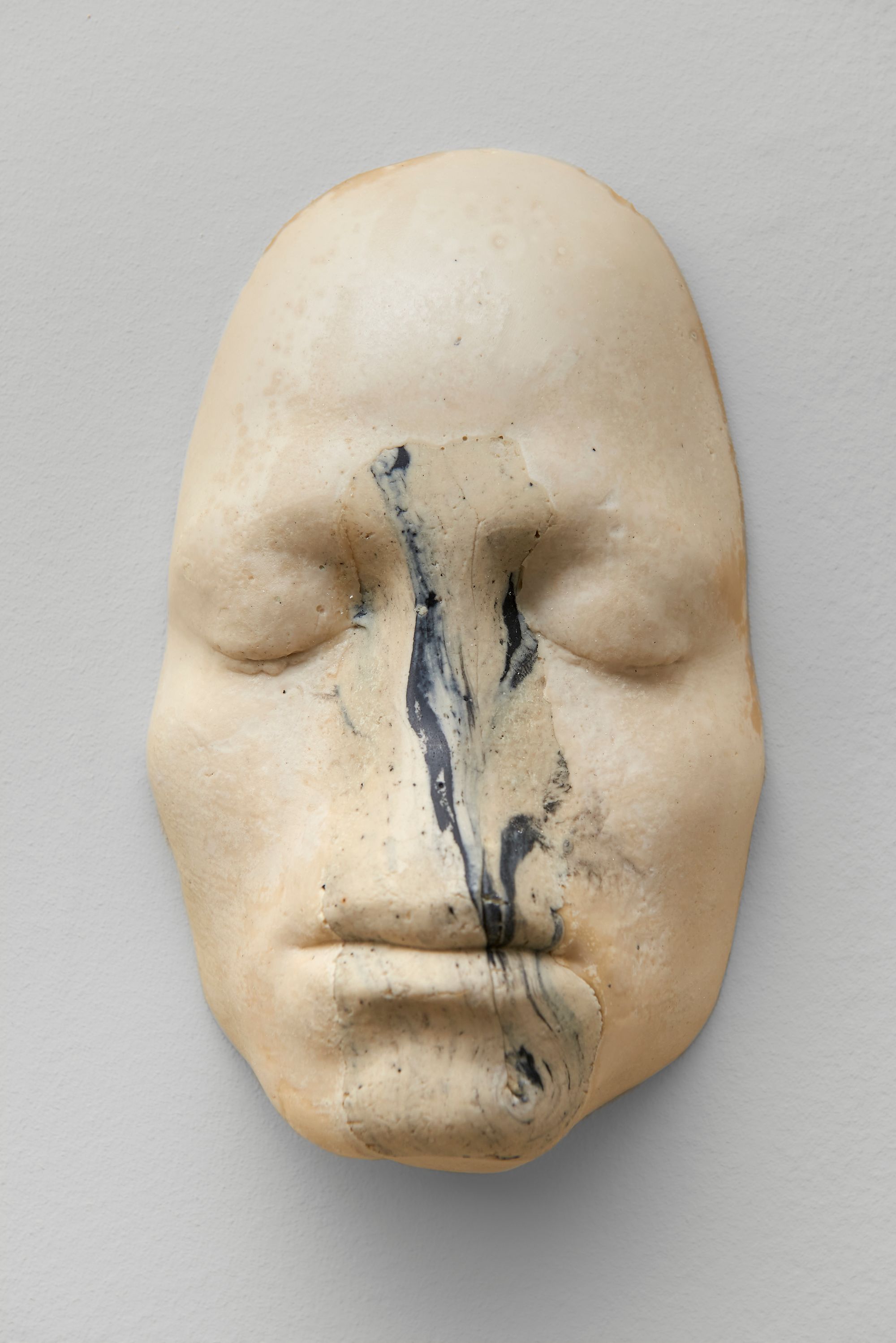

Maya Beverly, Untitled, 2023. Photo by Arturo Sanchez.

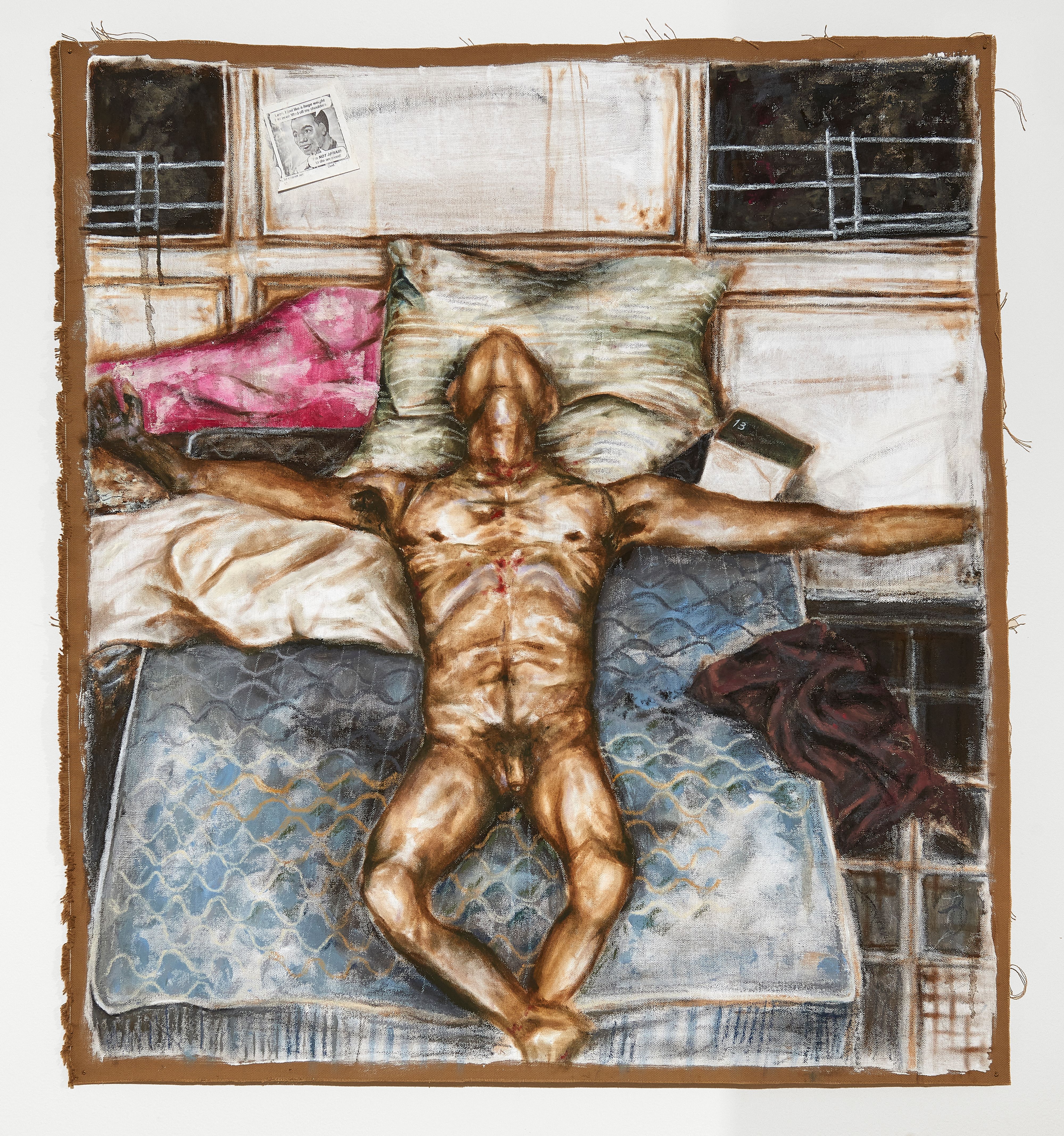

Yves Craft, God in his heaven, 2021. Photo by Arturo Sanchez.

Tariq Dixon and Phillip Collins occupy different corners of the art and design world: Dixon is the founder of furniture and product design studio TRNK, and Collins is the founder of Good Black Art, which operates as an e-commerce platform for collectors as well as a mentorship program for emerging Black artists. But when they started to compare their experiences as curators, they used the parallels they found as the foundation for an investigation into boundaries set within the market around what is considered art, design, and craft — and how the rigidity of these definitions don’t always apply to the artists whom they work with, nor those who’ve explored these questions in the past. Centered around a conversation on freedom, choice, and materials within contemporary and historic Black culture, MOLDED is a group art exhibition running at TRNK’s Tribeca showroom through the end of February, featuring new work that includes an assembly of whimsical ceramic, sculpture, and textile pieces by artists Ambrose Rhapsody Murray, Hamzat Raheem, Maya Beverly, and Yves Craft.

Maya Beverly, Untitled, 2023. Photo by Arturo Sanchez.

Installation view of MOLDED at TRNK’s Tribeca showroom. Photo by Arturo Sanchez.

Hamzat Raheem, Michael, 2022. Photo by Arturo Sanchez.

Vivien Lee: What is the background story of Good Black Art? What were you doing before launching the platform, and what’s been some of your proudest moments as a curator and mentor?

Phillip Collins: After living and working in Asia for nearly ten years as an international marketer, I returned to the US in 2017 and moved to New York. That period of time was challenging. I was experiencing reverse culture shock and it was my first time working in corporate America, plus the general hardships of living in New York City and unpacking the past trauma of my early years as a queer Black man growing up in the south.

I started collecting art that year as a form of activism and healing — a way to piece my nuanced journey together. I focused primarily on emerging Black artists from all over the world, but once you start getting into the nitty gritty of any new passion, you see all of its barriers to entry — and art has quite a few. The largest ones for me were lack of industry knowledge, lack of access, and high cost. When I talked to artists, they had similar challenges as well. There was a moment where I realized these challenges weren’t going to go away, and that’s how Good Black Art started. It started out of me being frustrated and wanting to solve a pain point for artists and collectors.

I launched the platform in September 2021 and now we work with over 45 artists from all over the world. We’re really proud of what we’ve been able to create in that short period of time. And it’s a very personal brand, because I remember what it was like growing up a queer Black creative in a rural white southern town and feeling like a unicorn. We provide a roadmap for artists starting off and say look: here are some ways you can succeed, here are some financial options, here are your legal options, here are some ways we’ll help you promote your work.

Ambrose Rhapsody Murray, I got diamonds at the meeting of my thighs, 2023. Photo by Arturo Sanchez.

What are some hopes that you and Tariq both have for the next generation of Black artists?

Tariq Dixon: For me, it's the ability to tell a range of stories through diverse narratives. I feel like even when the art and design worlds do represent or “celebrate Black artists,” it's often within a very narrow framework or a prescribed narrative. Sometimes identity politics can overshadow an individual’s work, too. When identity politics become secondary, that almost feels like transcendence.

PC: I would agree with Tarek. My biggest hope for the next generation of Black artists is to have that freedom to express who they are using whatever medium while continuing to push our traditions, techniques, and materials forward in new and exciting ways. That’s one of the beautiful things about this exhibition: these traditions and materials have been used forever within Black culture around the world.

Maya Beverly, Luna, 2023. Photo by Arturo Sanchez.

Hamzat Raheem, Artificial Black Face, 2023. Photo by Arturo Sanchez.

Maya Beverly, Little Port, 2023. Photo by Arturo Sanchez.

What drew you to each of the artists in this particular group show?

PC: I think these four artists find new and interesting ways of presenting who they are through unique materials. They’re effective communicators, and I’m overall drawn to their craftsmanship. Another thing that’s important is that even though they each have a unique style, their works are in conversation with and complement each other.

What set the tone and name of this exhibition?

PC: One of the things we talked about in the very beginning was the tension in the market. Over the past few years I’ve had so many conversations with artists about their challenges being in this gray area between art and design. We’d discuss things like: How do I identify? Should I be an artist or a designer? Which medium captures my narrative but will also sell well commercially? The exhibition acknowledges those gray areas while celebrating the legacy of craftsmanship that continues to thrive in our community.

TD: We definitely wanted this exhibition to be a celebration and to be affirmative despite some of the impetus and critiques of the market, as Phil stated. But it is Black History Month after all, so we wanted the exhibition to be a celebration and really focus on the positive quality of these four artists while beckoning to their relationships to history and heritage.

The word Molded specifically came about because it’s a celebration of materials that some may deem craft or historically rooted in craft, and we wanted to really own that. Also the idea of these contemporary emerging artists being influenced and molded by history.

Yves Craft's works in MOLDED at TRNK’s Tribeca showroom. From left: o eros, 2022; will endure, 2022; o jove, 2022. Photo by Arturo Sanchez.

Would you say that craft is often deemed less refined than art?

TD: There are definitely layers of bias in how the market responds to or favors certain mediums over others. I think generally, the market favors mediums practiced primarily by men, and white men more specifically, which is a question interrogated often by female artists as well. Andrea Zittel is a white woman who embraced quilting as a fine art medium. And part of that was the critique of a medium that’s undervalued by the market because it’s something that’s largely practiced by women. They’re not necessarily new questions, but they’re ones still deserving of even more attention. The market favors traditional paintings for a number of different reasons, whether it’s gender or ethnic bias. It’s also easier to sell, right? They appreciate more quickly.

PC: There’s an artist who once told me that he was taught that the money is on the wall. Obviously that kind of explains what Tariq was just mentioning — that commercially there is a bias and a strong preference to sell works that can be hung like a painting. It’s something we were thinking about in this show: how can we can give that freedom to the artist to make what they feel is right for them to communicate who they are? It’s up to other galleries and curators to start thinking of ways to allow that freedom, and I hope to see more of that.

Yves Craft, Abel, 2021. Photo by Arturo Sanchez.