Exhibition view of You Stretched Diagonally Across It: Contemporary Tapestry at Dallas Contemporary, featuring Topos (2012) by El Anatsui. Photo by Kevin Todora.

Exhibition view of You Stretched Diagonally Across It: Contemporary Tapestry at Dallas Contemporary, curated by Su Wu. Photo by Kevin Todora.

For curator Su Wu, the construction of a tapestry offers an open landscape for material and conceptual exploration. Unlike photography or ceramics, practices that also fall into the “art versus craft” debate and whose materials are permanently transformed through the process of their making — film is transformed through light and clay through heat — weaving is uniquely mutable. “Tapestry is completely revocable,” Wu says. Every stitch can be undone. The curator, who is also a poet, co-founder of MASA gallery in Mexico City, and is working on a forthcoming book on contemporary Mesoamerican homes for Phaidon, likens the process to typing. “The very action of weaving is the same action of unweaving. It’s like hitting the delete key when writing.”

In You Stretched Diagonally Across It: Contemporary Tapestry, which is open until mid-October at Dallas Contemporary, Wu brings together an international group of 30 artists whose works explore the “very noble, human gesture” of creating tapestry. The show offers an opportunity to break with the usual taxonomic organizations insisted upon tapestry and to instead consider questions of style, storytelling, and glitch. Could we imagine a weave like a 0 or 1 of binary code? Can we appreciate tapestry for its materiality without isolating it within the realm of craft?

On the occasion of the exhibition, curator and writer Sam Ozer spoke with Wu over the phone to discuss her frustration with taxonomical practice, the pitfalls of authenticity in assigning value, and the ever-sticky questions around art versus craft. This dialogue began when Ozer interviewed Wu and the other MASA founders for PIN–UP in 2020 and has continued through their friendship and discussions over the years.

Exhibition view of You Stretched Diagonally Across It: Contemporary Tapestry at Dallas Contemporary, featuring Topos (2012) by El Anatsui. Photo by Kevin Todora.

Kira Dominguez Hultgren, Our Daily Parenthetical (2025). Photo by Shaun Roberts, courtesy of the Artist and Eleanor Harwood Gallery.

Sam Ozer: What was the instigator for this show, and how does movement — across geographies, makers, and forms — come into play?

Su Wu: I feel like this is something that you and I have talked about a lot — all of the ridiculous romantic associations that get thrust onto craft and how stark the contrast of how we view craft objects versus “art” objects becomes when “craft” enters the art world. There are numerous unexamined assumptions that we make about craft. One is the historical ethnographic imposition of how textiles have been displayed as originating from a single place at a specific time. However, that doesn’t truly reflect the histories of migration or our capacity to hold plural identities. This idea of travel became an integral part of the show, exploring the migrations and movements of people, materials, and ideas.

You’re a curator, but you’re also a poet, and I feel like your language practice always seeps into your curatorial practice, particularly in how you create connections between objects. There is always a level of deconstruction before you finalize the concept. How did this project come together in relation to that instinct?

I was frustrated with the idea of a well-defined space around tapestry and craft, and I wanted to unravel that a bit. As a design curator, I’m offered so many taxonomical exhibitions. “Why don’t you do a show about chairs?” Instead of developing a concept, there is this idea that if the subject has some sort of historical category or genre association, that should be enough of a throughline. For this exhibition, I wanted to explore the term “tapestry” in depth. Through this process, I was able to define for myself a tapestry as an object where the surface and the substrate are indistinguishable and co-arising. It’s an image that is also the matter. This show is also a conversation about what happens when so much of our experience of images at the moment is mediated by something, which is often a screen. What does it mean to see an object or an image in real life? Many of the works serve as reminders that digital images are also made of something. As much of the language surrounding digital images becomes increasingly effervescent — like the concept of the cloud — I wanted to remember that they are made from real materials and labor, even if it is anonymous.

Lee ShinJa, Screen (1979). Photograph by Unreal Studio, Courtesy of the Artist and MMCA Korea.

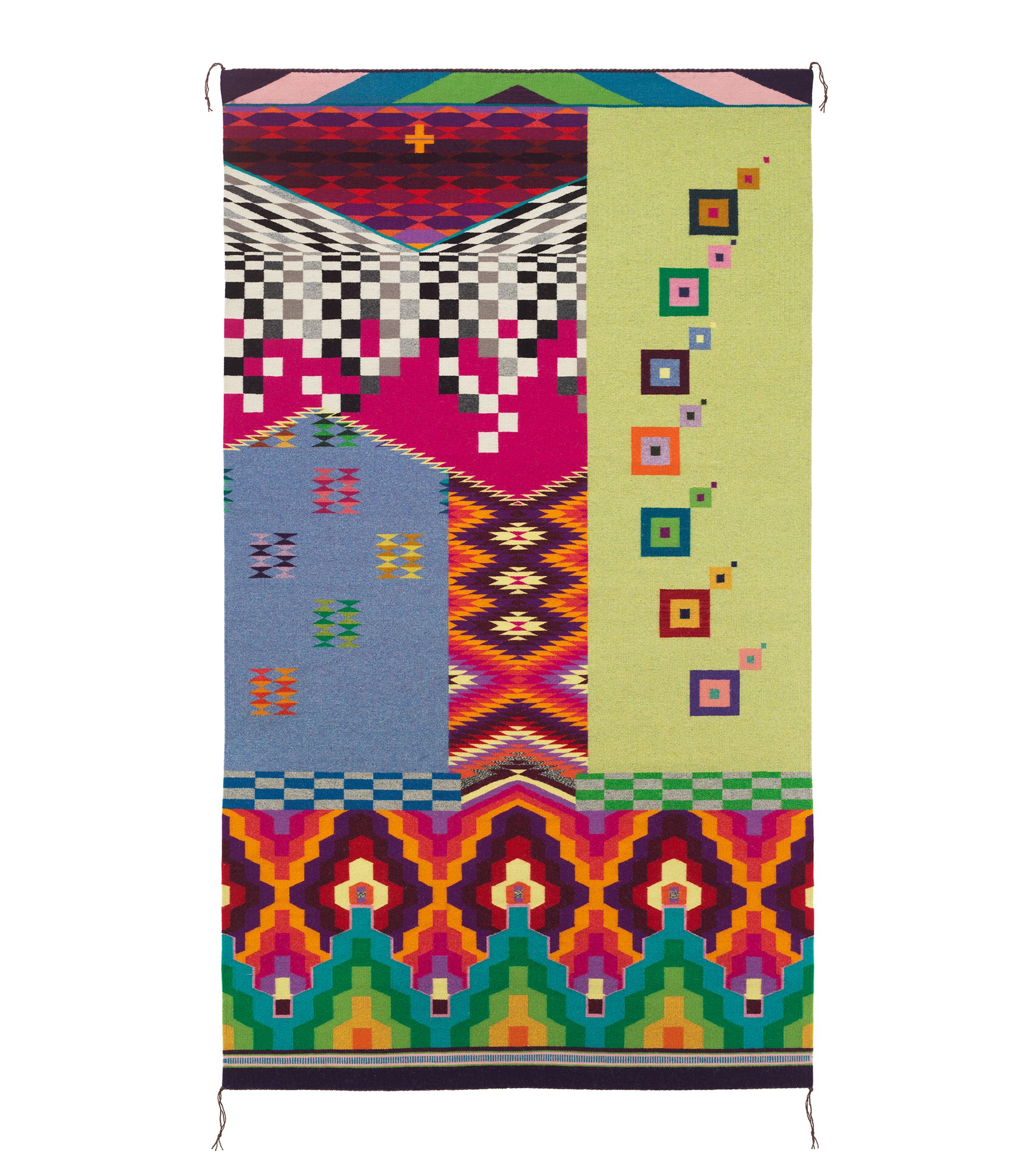

Melissa Cody, Motherboard Vibrations (2024). Courtesy of the Artist and Garth Greenan Gallery, New York.

How do the artists in the show respond to that? Why make a tapestry, or a physical tapestry, or say, a digital image?

They are all responding to it differently. Some of the artists discuss the transformation that occurs in an image during the process of being built up through tapestry — a technique that involves weaving, layering, and other methods of craft. When something transforms not in its superficial appearance, but in its substance, it could look the same as it would have looked in another medium. Still, this has material significance, which becomes very integral to the work. Most of the artists are thoughtful about the correspondences between the material, what the work looks like, or the surface of the image. I also wanted to think of time as the last purview of the human, rather than falling into the often reductive conversation around craft that reduces it to a romantic notion of the handmade, without really examining what is valuable about the handmade. Like, why is the fact that something takes a long time to make considered a virtue? Why is tradition considered a virtue? That was another thing that came up frequently in this exhibition. There’s this idea that something has value just because it’s been done a certain way.

Well, it becomes about this idea of expertise, no? Which, on some level, could be quite interesting for sharing knowledge and tradition, but also potentially limiting in terms of added value.

Exactly. This is often glossed over, but the distinction is in the technique and the expertise, not in the superficial appearance. That’s the mistake that I think often happens in craft is this preservation: the appearance of something rather than thinking about the way that it’s made as being a skill that’s worth considering. There’s an unexamined problem with the concept of originality in relation to craft and design, which is a difficult topic to discuss in the context of tradition. It’s something that comes up a lot when we consider where authenticity stems from and who is granted the virtue of genius and originality, and/or wisdom and tradition.

Thinking about this idea in the context of the show, this conversation reminds me of Yto Barrada’s work, Geological Time Scale, where she assembled a group of mid-twentieth-century, primarily monochrome Beni Mguild, Marmoucha, and Ait Sgougou pile rugs from Western Central, Middle Atlas, Morocco. There is a comment on formalism that is inherent within that piece, but it layers that question about what “good design” is with history and theory.

That piece is also interesting because it speaks to work Louis Hubert Lyautey (1854–1934) did in the early 20th century of cataloguing traditional, authentic Moroccan rugs and tapestries. He was the first general of the French protectorate of Morocco, a public intellectual, lover of the arts, and a preserver of craft. He was a character in a Sherlock Holmes mystery, and is said to have inspired Proust. His catalogue has become somewhat of the definitive text on what is considered “authentic” in terms of craft, but Lyautey left certain things out of this taxonomic guide out that he simply did not like or that he deemed were not elaborate enough. His idea of authenticity would not include these monochromatic pieces that Yto uses; he would think that these were too simple. One reading of Yto’s work is that it’s this excavation of the works that [Louis Hubert Lyautey] did not consider authentic enough. By layering them in this strata, Yto attempts to represent a certain geographical area, such as a mountainside and geologic time.

Exhibition view of You Stretched Diagonally Across It: Contemporary Tapestry at Dallas Contemporary, featuring Yto Barrada's Geological Time Scale, assembled group of primarily monochrome Beni Mguild, Marmoucha, and Ait Sgougou pile rugs from Western Central, Middle Atlas, Morocco, mid-20th century (2015). Photo by Kevin Todora.

Yto recontextualizes those tapestries. The question of the handmade becomes less of a touchpoint due to the way she uses them as a tableau.

Some people would say it’s a form of communication. I think of it through my interest in the distinction between design and art through the lens of excess. Is a work intended to be an object of excess or efficiency? There are many designers who work within an efficiency framework, as well as numerous individuals who create textiles, tapestries, or baskets within this framework. I mean, human hands make computer chips and make baskets. I still need to verify this, but someone told me that baskets are still made by hand because it’s still the fastest and most cost-effective way to make them.

I believe that. A certain dexterity is required for those movements.

That’s an efficiency question. For me, the “excess” question is about an excess of attention towards craft that goes beyond simple functionality.

I love this idea of using “excess” for categorization and to add a factor beyond form, function, and use value into these conversations. I also love that you brought up the issue of communication. While reviewing the exhibition, I thought about textiles in Latin America and the various cultures that utilize them as record-keeping or communication devices. I was reminded of quipus, which are knotted textile record-keeping devices traditionally used in the Andean South America. The Inca civilization used them to record census, military, and historical information, as well as poems, and today they are used by some communities to track herd numbers. The artist Cecilia Vicuña now uses them as a way of weaving poetry into the lineage of her work. I’m also curious about forms of language and communication in Hellen Ascoli and Negma Coy’s works in the exhibition. You invited Ascoli who then invited Coy to make a new work responding to her piece. The result was a three-panel tapestry by Coy which features a palindrome in Mayan glyphs. Their works mirror each other.

For me, the Hellen Ascoli work [luzAzul] is so physical. You can see the pulling and tension created from the back-and-forth weaving motion of the lines as they arrive in a tortuous sequence. Its physicality reminds me of the back-and-forth motion of typing on the computer, which also goes back to the idea of excess and why we make tapestries. In all of its material significance — or purported material significance — tapestry is a work which can be completely undone. It’s the same with writing. You can type 20,000 words, and they can be undone. A tapestry is an object that doesn’t change in the making of it. It can revert to its raw material and be unwoven. It’s not like ceramics, where the material is thrown into the fire and its form changes states. The very action of weaving is the same action of unweaving. That feels like a very noble, human gesture to me.

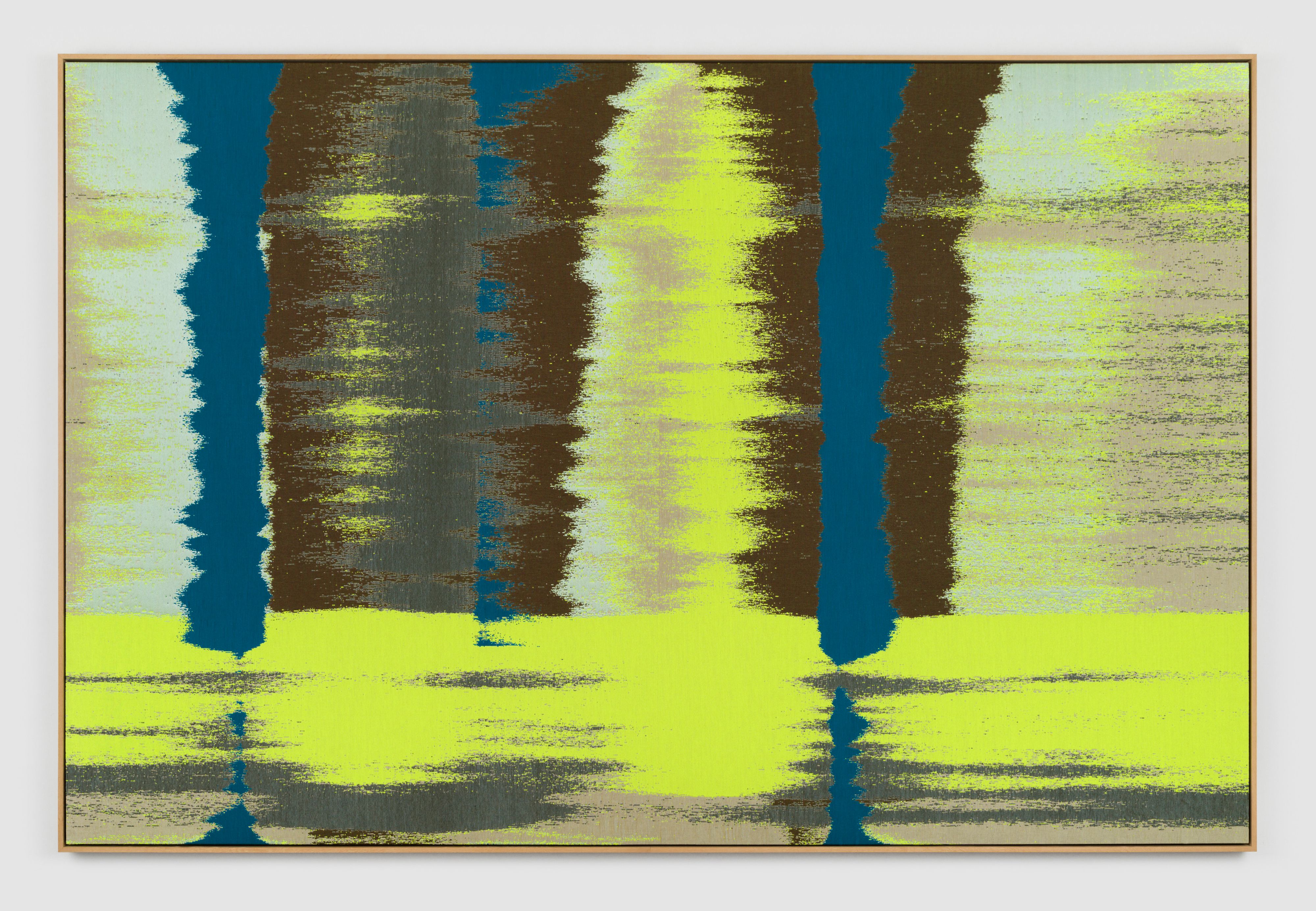

Mika Tajima, Negative Entropy (Deep Brain Stimulation, Yellow, Full Width, Exa (2024). Photo by Charles Benton, © Mika Tajima, Courtesy of the Artist and Pace Gallery.

It’s quite beautiful to think of this pairing between the physicality and infinity of weaving and writing. I also like the relation between writing on a computer and the binary code of of 0s and 1s for translation and the concept of a single stitch in a tapestry as a button, let’s say. For Vicuña, and to an extent Ascoli and Coy, the knots or weaves in the tapestries become markers of speech, for the others, such as Mika Tajima they are signals of typing on a computer. Can you speak to this?

Mika Tajima’s work, Negative Entropy (Deep Brain Stimulation, Yellow, Full Width, Exa) (2024), is created of these tiny actions which are not commensurate with the scale of the final artwork – it was at the absolute limit of the loading dock at Dallas Contemporary. [Laughs]. It depicts this small, isolated brain synapse. Analia Saban also brings in the micro and digital discussion with Tapestry (Computer Chip, TMS 1000, Texas Instrument, 1974) (2018) as she weaves the structure of a computer chip in paint. Jovencio de la Paz brings up the question of the handmade with Blue Grid 1.0 (2024). There’s always that weird thing where it’s like, “Oh, I can see your hand in this.” You can see imperfection and the human touch.

And you’re not convinced that this imperfection around the human hand inherently gives the work value?

I think it’s an assumption that’s worth an exploration. Jovencio creates a weave structure for a perfect grid, runs it through algorithms for cellular evolution or disease modeling, and then the piece starts to unravel. In some places, it becomes overly dense, while in others, it becomes sparse. In these instances, it’s the algorithm that is creating the superficial appearance of imperfection. I think a lot about the idea that damage is expressive or is a reflection of some sort of trauma, libido, or belief — these great human purviews seemingly contra the machine. This work is a good example of what I’m trying to do with this exhibition: to find these little moments that poke at what we think of as craft and what we consider valuable within it.