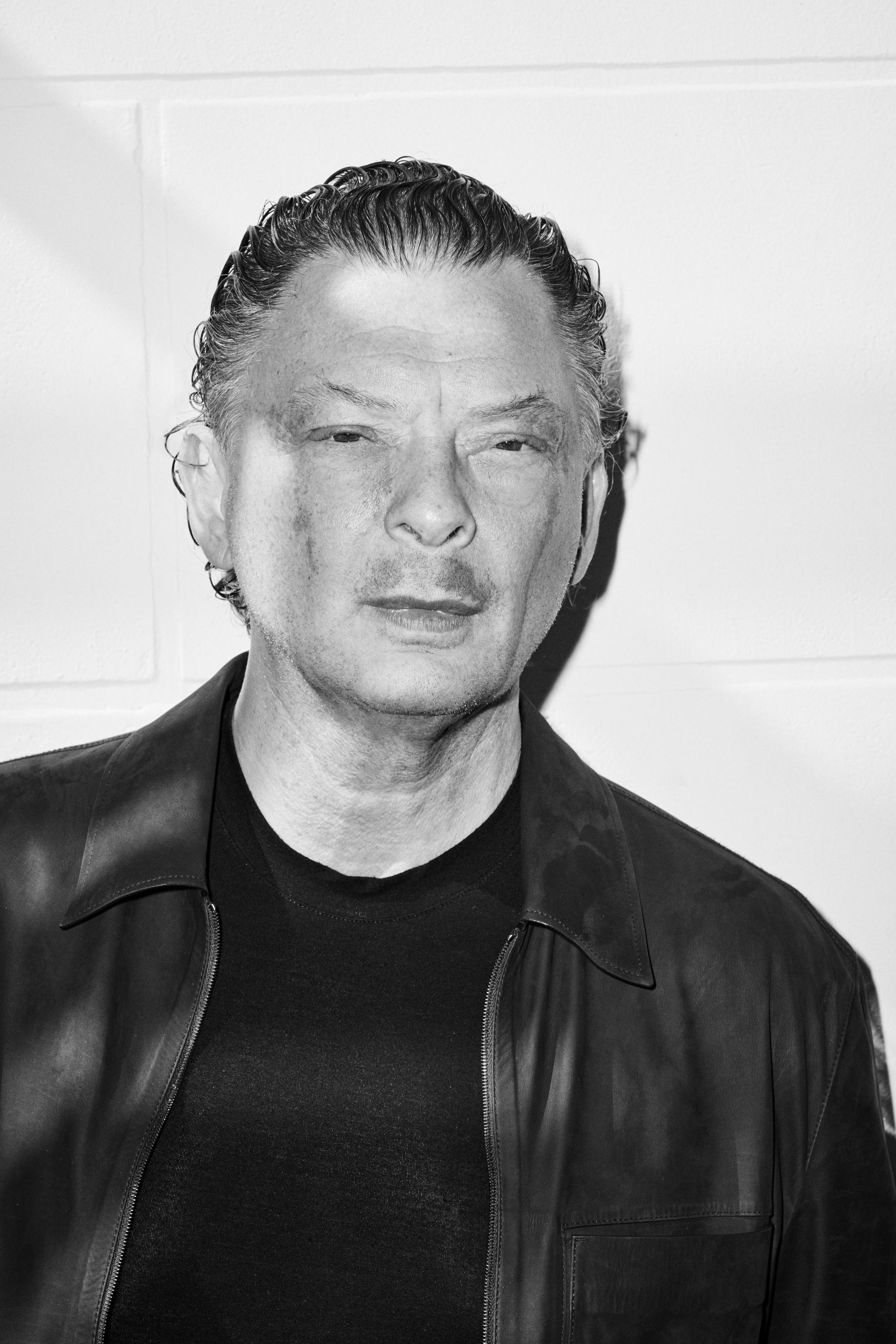

Piero Gandini photographed by Jeremy Liebman for PIN–UP.

Piero Gandini photographed by Jeremy Liebman for PIN–UP.

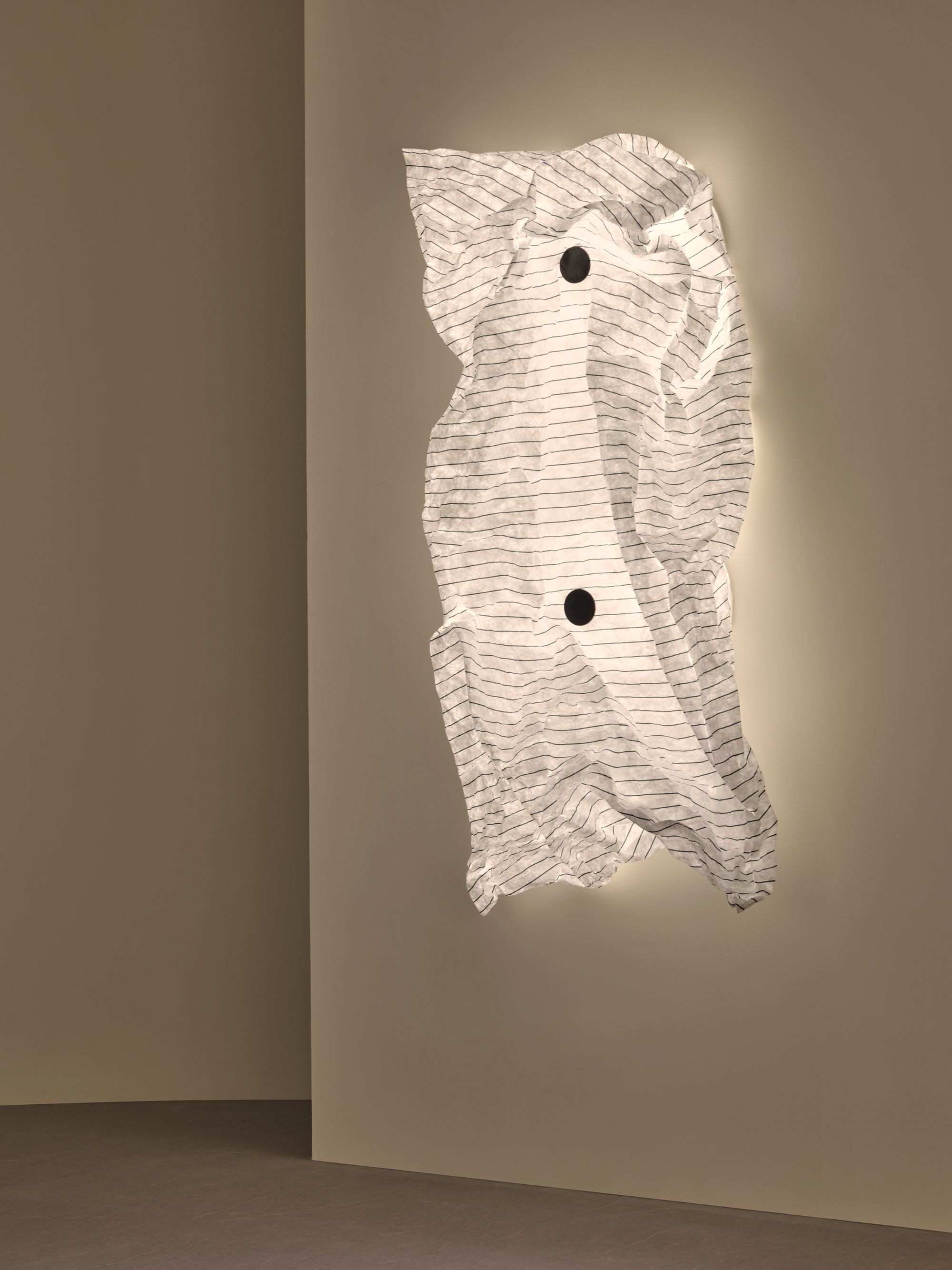

Maap wall light by Erwan Bouroullec at Euroluce 2025. Photography by Gianluca Bellomo.

In the design world, Piero Gandini is a rare breed: part old-school industrialist, part enfant terrible. Now in his early sixties, the Italian entrepreneur is the Executive Chairman of the Flos B&B Italia Group, a sprawling design empire that includes B&B Italia, Flos, Louis Poulsen, Maxalto, Arclinea, Azucena, Fendi Casa, Audo, and Lumens. Of these, Flos remains his spiritual home — co-founded by his father in the 1960s, it’s the company Gandini grew up in and then ran from 1996 to 2019, transforming it from a respected mid-sized brand into a 300-million-dollar powerhouse. Gandini has always insisted that design must resist the seductions of luxury for luxury’s sake. For him, ideas — not price tags — are what matter. A fierce defender of legacy, he’s also been instrumental in championing new voices: under his leadership, Flos helped launch the careers of now-established talents like Konstantin Grcic, Michael Anastassiades, and Formafantasma, to name but a few. His departure from Flos — and from Design Holding, the larger group it had by then become part of — was by all accounts dramatic, a grand conclusion to Salone del Mobile, the commercial anchor of Milan Design Week. Equally unexpected was his return in January 2025, after a six-year absence. What convinced him to come back? How has the design landscape shifted since the end of the last decade? And does he still think, as he once told PIN–UP, that the design world is becoming too bourgeois, split between nostalgia and expansion? Sit down with the ever-candid Gandini for an hour, and you’ll get the answers — and more.

SuperWire floor lamps by Formafantasma. Photography by Gianluca Bellomo.

Piero Gandini photographed by Jeremy Liebman for PIN–UP.

SuperWire table lamp by Formafantasma. Photography by Gianluca Bellomo.

Piero Gandini photographed by Jeremy Liebman for PIN–UP.

Felix Burrichter: You left your position as executive chairman of the Flos B&B Italia Group in 2019. What made you want to return six years later

Piero Gandini: The past six years have been a tumultuous time for the industry — COVID, followed by a period of revenge spending, and then the crisis we find ourselves in again. So when I ran into Marco De Benedetti [Executive Chairman of the Carlyle Group, the global investment firm that manages the Flos B&B Italia Group together with Investindustrial] a few months ago, we started talking about the past few years and, let’s say, the certain amount of confusion in the group’s management. We met a few times — super secret — and eventually arrived at an agreement. Money wasn’t a driving factor for me. The issue runs much deeper. What mattered most was refining a strategic focus, a clear direction for the group. I didn’t want the reasons I left in the first place to be back on the table.

What were those reasons?

Clearly, the company was going in a speculative direction — the idea was to build a big group and go for a fast exit, from investment to IPO, in a very short time. I felt it was a hazardous way to approach things. On top of that, their economic model was based on the luxury world, mainly fashion. When I left in 2019, I told them: This is not how design works. Opening a lot of shops doesn't mean your performance improves. Having 10,000 consultants, or making the organization more complicated and structured, doesn’t improve the business either. At the end of the day, conceptual design is a simple business. It’s the intangibles that are complex — the reasons behind creating a new product, the quality, the attitude, the identity of the company. It’s really about making a good product and having a good sales organization — people who believe in the company and in what they’re doing. But things became unnecessarily complicated. COVID didn’t help, of course. I told them: if you want to put things back on track, you have to prioritize industrial logic over financial logic. The people running the processes need to know the design world, be data literate, and, most importantly, be passionate about what they do. We need to bring back the “why” — and put the product at the center again.

Piero Gandini photographed by Jeremy Liebman for PIN–UP.

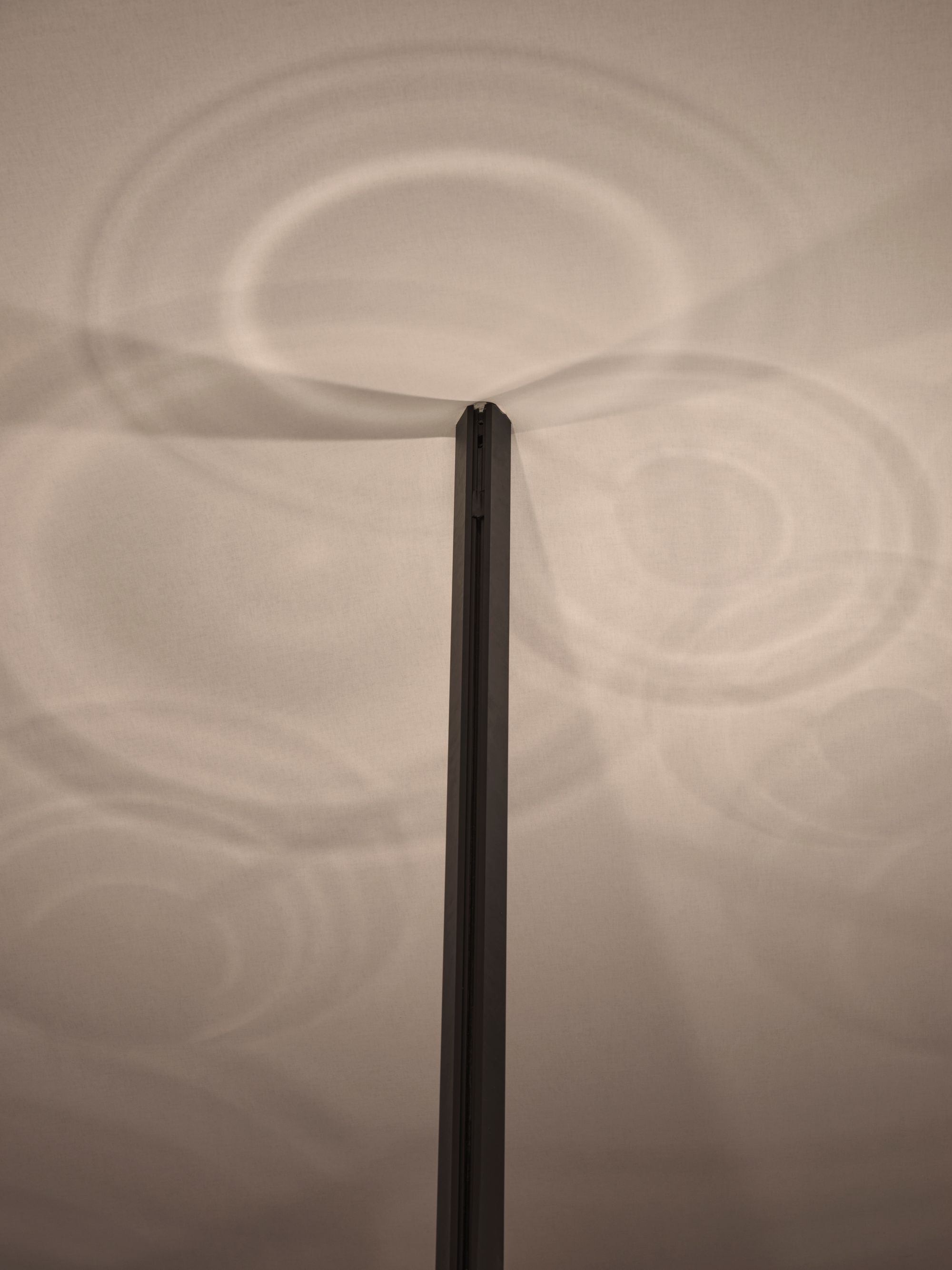

Detail of Linked light by Michael Anastassiades. PPhotography by Gianluca Bellomo.

You have the same title as when you left: Executive Chairman of the Flos B&B Italia Group. How would you say your approach to leadership has changed?

The difference is that now we’re all driving in the same direction, so things can actually get done. Before, it wasn’t possible. It was too complex, too fragmented. It’s still a big challenge, and it will take time, but I’m confident we’ll get things back on track. When I came back in January, naturally, my first focus was Flos — especially with Euroluce happening in April. Flos is a bit smaller than when I left. Prices have increased more than 30% in the past five years, so in reality, they’re selling fewer pieces. On top of that, we’ve been creating an enormous number of color variations for each product — which raises questions around coherence. When you start offering 10,000 greens and 10,000 pinks for a Castiglioni product, it starts to lose meaning. At the same time, if you look at the top 20 best-selling Flos products, not a single one comes from the last five years. I love the Flos icons — they’re my family heritage, my life, my blood, my memory. But if you only focus on the icons, you're essentially talking about six or seven products from the 1960s and 70s. It begins to look like you’re hiding your new work. So my first decision was to create a conceptual book. Let’s tell the story of our identity, our intentions, our values. Let’s show people who we are now.

Amid the many novelties you showed during Euroluce earlier this year, you also reintroduced a classic: the Seki-Han light by Tobia Scarpa from 1963. What made you want to bring it back?

It was a lamp that was in my childhood home. I’d always been told it was just a prototype. So I called my father’s old accountant — she has an incredible memory for the company’s early years — and asked if that was true. She said, no, not at all. In fact, it had been on the market briefly, I think from 1963–65, but it wasn’t a success. The wooden construction made it difficult to produce, so they quickly phased it out. But the product is beautiful. One day, I put it in the trunk of my car and drove to see Tobia, who is now in his nineties. I told him, Tobia, this design is fantastic — let’s evolve it a bit and adapt it for today, with new technology. He was enthusiastic. We started working on it just one month before Euroluce! But this is something people recognize in me: I know how to push a process. And honestly, it was one of the sweetest things I’ve worked on.

I also called Konstantin [Grcic] with an idea for updating his Noctambule series from 2017. The Flos R&D team came to me to help figure out how to retrofit the series for modern tech. We spent an entire afternoon with Konstantin trying to find a solution — with no luck. But I kept saying, Come on, we can figure this out. Eventually, we did. And when it clicked, the R&D guys were genuinely happy. One of them gave me a hug and said, Piero, it’s good to have you back. Moments like that — when there’s shared excitement and things come alive again — that’s why I came back. To help reignite that sense of purpose and energy.

Seki-Han floor lights by Tobia Scarpa displayed during Euroluce 2025. Photography by Gianluca Bellomo.

Detail of the new Seki-Han pendant light by Tobia Scarpa displayed during Euroluce 2025. Photography by Gianluca Bellomo.

We’ve discussed Flos, but I’d like to talk about the other companies under your umbrella. Louis Poulsen, for example.

Poulsen is much less complicated than Flos. For one, they don’t do much technical or architectural lighting, so the contract side isn’t very large. They focus on classic Scandinavian lighting design — and they do it well. It’s a well-marketed, well-organized company. Of course, like anything, there are complexities. But the identity is very clear. You understand why they do what they do, and where they want to go. That clarity makes a big difference.

And what about the other big powerhouse in the group, B&B Italia?

B&B is more complex — it’s a very big operation. I like to say it has several souls: B&B Italia, the main line, with its long history of design innovation by the likes of Bellini and Gaetano Pesce; Maxalto, which is more upscale, focusing on craftsmanship; Azucena, which carries the legacy of Luigi Caccia Dominioni; and Arclinea, for kitchens. It’s a group with an incredible legacy and enormous potential. But I want to revive the original spirit of B&B Italia — when designers worked with no fear, creating 32-foot-long sofas and wild bubble chairs. You don’t have to be crazy, but you do have to be visionary. You have to be courageous in this business. B&B needs to rediscover the pleasure of being on the line — of living a little more on the edge.

Nocturne by Konstantin Grcic featured in Flos's Euroluce's booth. Photography by Gianluca Bellomo.

Piero Gandini photographed by Jeremy Liebman for PIN–UP.

Nocturne by Konstantin Grcic featured in Flos's Euroluce's booth. Photography by Gianluca Bellomo.

You mentioned earlier that the investment group was modeling itself on the fashion world. But the difference, to me, is that in fashion — even within the big conglomerates — each house maintains a very distinct identity. In design, that feels less true. Everything’s starting to look the same. There's this push for a certain “tasteful” aesthetic, and it’s getting harder to distinguish between companies. Last time I interviewed you, you said design was becoming too bourgeois. Would you say that’s even more true now?

Oh yes. Even B&B Italia, which had a really edgy spirit in the beginning, has become a bit too bourgeois. The founder, Piero Busnelli, wasn’t a trained designer, but he had great intuition, vision, and passion. He built the company with a radical spirit. Ten years in, he realized there was also a market for the more bourgeois side of design — the interior decoration world — and so he created Maxalto as a separate line for that level of sophistication. It started with beautiful pieces by Tobia Scarpa. But to go back to your point about the business model: the people managing the money often don’t know how to manage companies with a deep cultural legacy. If we follow the fashion-world luxury playbook too closely, the story gets diluted. What I want to bring back is a sense of identity, pride, desire, and vision.

What’s the current climate in terms of where design is going, and in terms of trade? Are you concerned about U.S. tariffs?

It’s hard to say. Tariffs themselves aren’t what worry me most — it’s the political climate behind them. Why are we supposed to accept this kind of attitude, this kind of rhetoric? That’s more troubling to me than whether tariffs stay or go. As for the direction of design, I see two paths. One is to remain a product-oriented company. That means not growing too much, but cultivating vertically — keeping the same quality, the same passion. The other path is expanding into the international contract market, where homes and apartment buildings tend to be designed in a more standardized way. Or, in some cases, you try to follow both routes — you want to grow the company, but without compromising its legacy.

Maap wall lights by Erwan Bouroullec at Euroluce 2025. Photography by Gianluca Bellomo.

Jam Session floor lamps by Piero Lissoni, displayed at Euroluce 2025. Photography by Gianluca Bellomo.

One of the things I find interesting about the legacy of Flos is that it manages to be both aspirational and, at the same time, relatively accessible — at least in terms of product range.

Yes. And to me, frankly speaking, luxury is bullshit. A good product should be about the idea. If it’s made using traditional manufacturing or artisanal knowledge — fantastic. But if there’s no real idea behind it, what are you actually selling? Just a status symbol. That’s how luxury brands end up dividing people — who can afford it, who can’t. Who has power, who doesn’t. I hate that. What I like about design is that it doesn’t have to be luxurious. Fashion, on the other hand, is luxury by definition. That’s where the confusion starts — this idea that you need to manipulate people into spending a certain amount of money just to define themselves. But design doesn’t need to classify people in that way. We can make something expensive today and something affordable tomorrow — it’s about the idea, not the price tag. I believe in a freer, more horizontal world, where people don’t need a label to tell them what’s good. Where there’s some self-awareness, some curiosity. Where people have the intellectual freedom to decide for themselves.

You’ve always been a champion of new talent — starting with Starck in the late ’80s, then Konstantin Grcic, Michael Anastassiades, Formafantasma, and many others. It’s fair to say you’ve helped introduce some of today’s most important designers to the broader design world — not just in lighting. Where do you stand now on emerging talent? I imagine it’s a risk, especially when you’re steering the whole ship in this economy.

Honestly, the only real risk is not going for it. If you get conservative, you’re killing these companies. They need new ideas to survive. That said, some companies have this attitude of showing a new designer at any cost. They’re constantly chasing someone younger — but a lot of those designers don’t have the consistency to deliver over time. But if you’re not curious — if you’re not out there looking for the avant-garde — then you’re not doing your job. It’s like being a book editor. You have your classic writers you always go back to, sure. But you’re always scouting for new voices. It’s just part of the work.

Piero Gandini photographed by Jeremy Liebman for PIN–UP.