Model for the Paul Pfeiffer: Prologue to the Story of the Birth of Freedom exhibition. Courtesy of the artist and Büro Koray Duman.

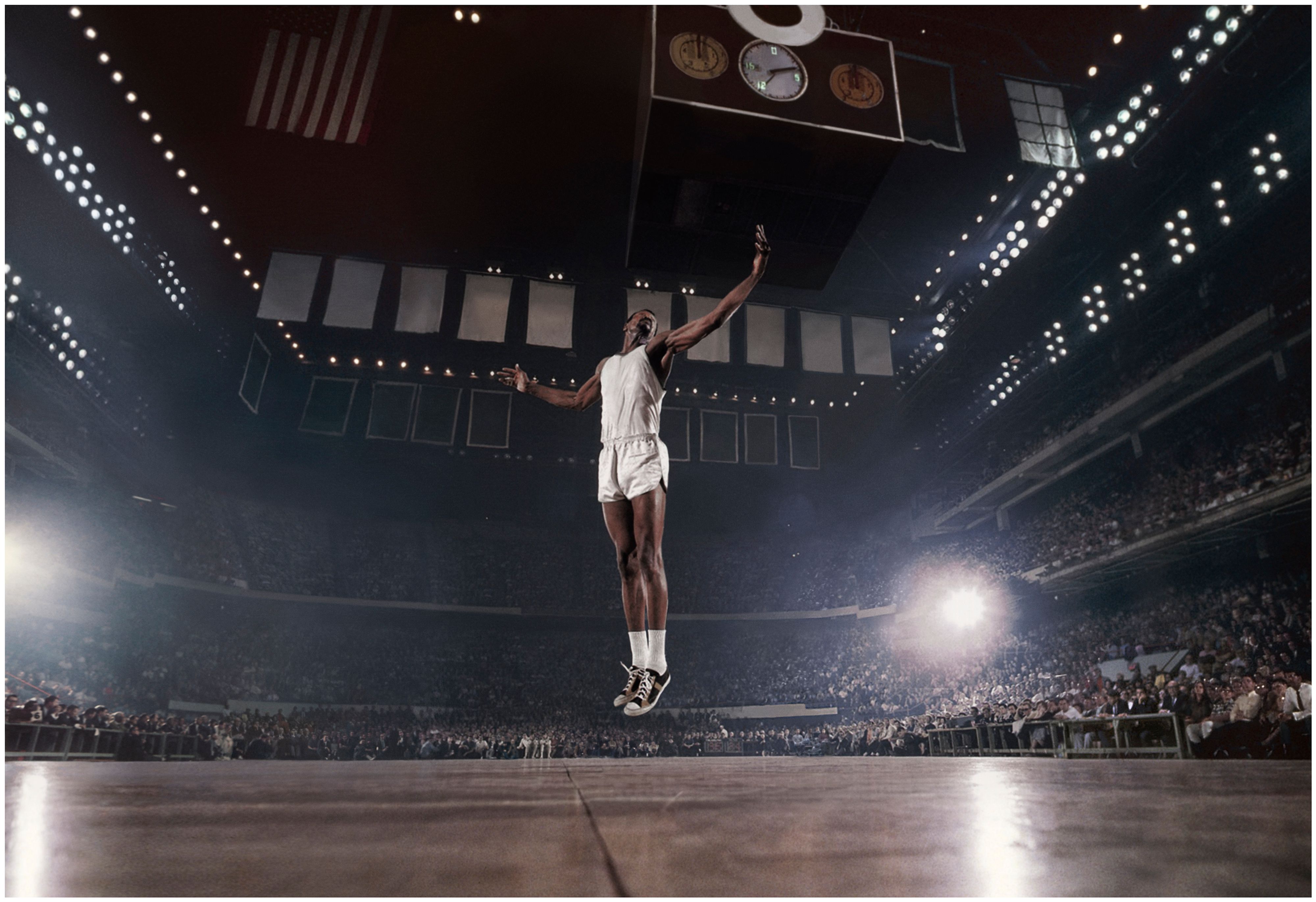

Paul Pfeiffer, Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse (30), 2015. Fujiflex digital C-print; 48 × 70 in. (121.9 × 177.8 cm). Private collection. © Paul Pfeiffer. Courtesy of the artist; Paula Cooper Gallery, New York; carlier | gebauer, Berlin/Madrid; Perrotin; and Thomas Dane Gallery, London.

Tucked into a discreet passageway of artist Paul Pfeiffer’s traveling 25-year retrospective — designed in collaboration with architect Koray Duman, and now on view at the MCA Chicago — the eponymous film work, Prologue to the Story of the Birth of Freedom (2000), pictures a disappearing act. The two-channel film features movie director Cecil B. DeMille’s overture to his 1956 Technicolor film The Ten Commandments, emerging on stage from behind the pale blue damask and gold-fringed curtain only to vanish again. He is about to introduce the story of Exodus, one of the five books of Moses, but the speech dissolves before it begins. The words that compose the title of both the work and the exhibition are never uttered.

Known for his meticulous video manipulations and use of pop culture to deconstruct systems of power, Pfeiffer’s practice explores the visual languages of sports, celebrity, and spectacle to expose the underlying structures of race, religion, and empire. His works are held in major collections around the world, and his long-awaited retrospective traverses multiple continents and cultural contexts. For this ambitious presentation, he partnered with Duman, an award-winning architect and founder of the New York-based studio Büro Koray Duman, whose civic-minded designs emphasize the role of spatial storytelling in public life. The collaboration spans three venues — MOCA Los Angeles, Guggenheim Bilbao, concluding at the MCA Chicago — with each iteration reimagined in response to the architecture of its host site.

In the original Prologue, DeMille follows the phrase itself — the birth of freedom — by posing a binary: “Are men the property of the state? Or are they free souls under God?” It is a question meant to dramatize how a moral conflict in ancient times might find its footing in the mid-century United States. This, of course, falls apart in a contemporary context, as our political climate is marked by an increasingly unstable democracy, the dissolution between church and state, and the resurgence of white Christian nationalism in public discourse. As we know, “freedom” is less a neutral invocation of liberty than a veiled assertion of dominion. In Pfeiffer’s version, this voice is gone — transforming the scene instead into something spectral, suspended. Reflecting on how the show draws from structures of religion, government, and the public commons, Duman and Pfeiffer sat with curator and author Stephanie Cristello to discuss the haunting elements of architecture and culture that guide the exhibition and its design.

At the MCA, this unfolds as a sequence of charged spatial encounters — hushed, chapel-like chambers that make use of the museum’s arched galleries, where viewers drift through echoes, shadows, and screens. The result is less a retrospective than a ritual: a ghostly procession through images and our memory of them to see how these expressions of devotion manifest from the masses to the intimate. We begin in the year 2000, as the arc of Pfeiffer’s practice builds to our present moment.

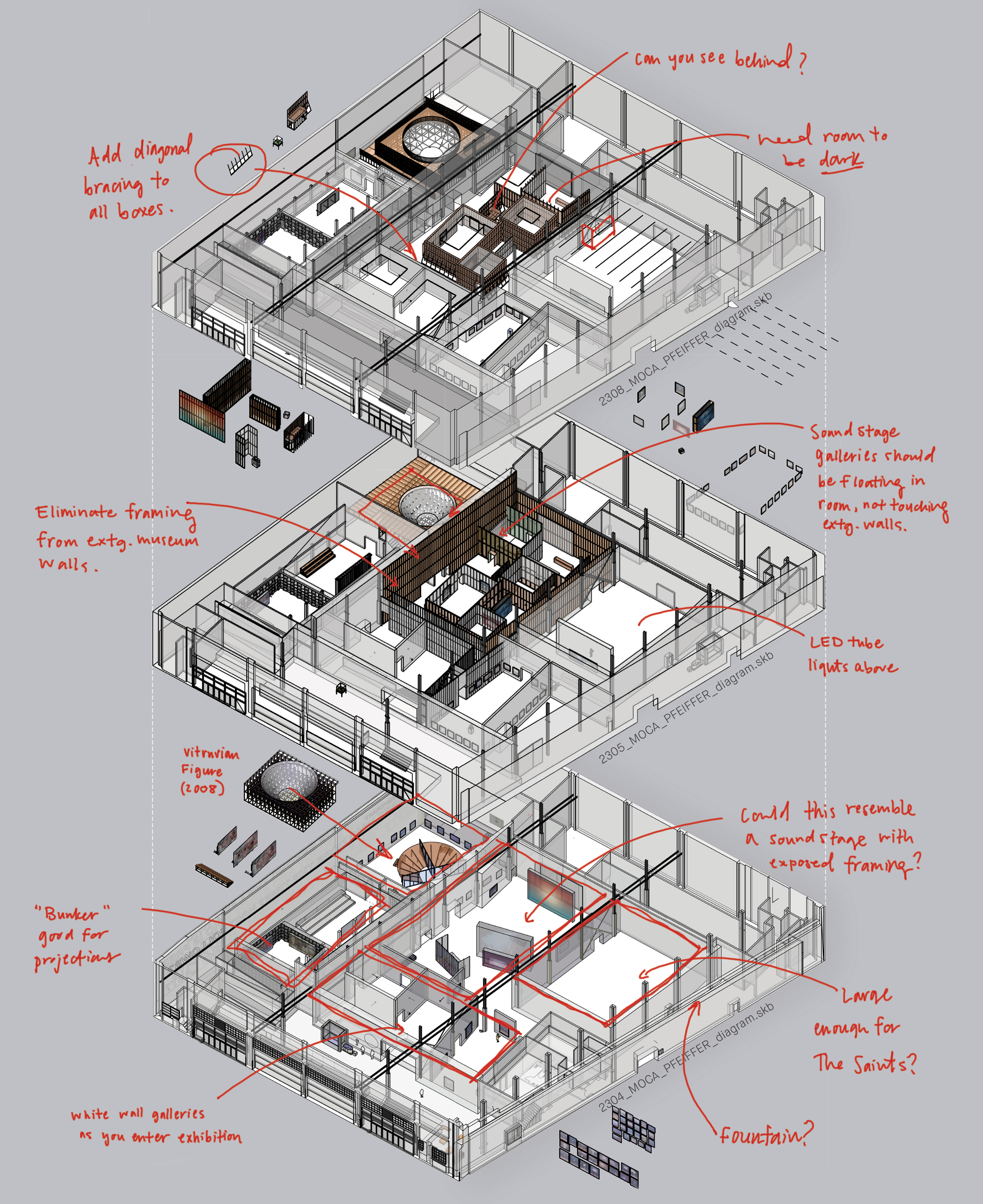

Model for the Paul Pfeiffer: Prologue to the Story of the Birth of Freedom exhibition. Courtesy of the artist and Büro Koray Duman.

Diagram for the Paul Pfeiffer: Prologue to the Story of the Birth of Freedom exhibition. Courtesy of the artist and Büro Koray Duman.

Paul Pfeiffer, Prologue to the Story of the Birth of Freedom, 2000. Two digital videos (color, sound), LCD monitors, and metal armatures; 5 1/4 ×16 × 5 1/2 in. (13.3 × 40.1 × 14 cm); 4 minutes and 6 minutes. Collection of Chris Vroom, New York. © Paul Pfeiffer. Courtesy of the artist; Paula Cooper Gallery, New York; carlier | gebauer, Berlin/Madrid; Perrotin; and Thomas Dane Gallery, London.

Stephanie Cristello: The exhibition places an emphasis on the crowd versus the individual toward a politics of scale, where the body is dwarfed, enlarged, or conspicuously absent. In addition to the obvious allusions to religious spaces, I wanted to start with the other public sites embedded within the exhibition — the stadium, the boxing ring, the ice rink, and then, of course, the galleries themselves.

Paul Pfeiffer: I was already thinking of exhibitions in terms of a wider kind of choreography, but to work comprehensively with an architect like Koray in relation to how people experience objects, and especially video, in an exhibition spanning 25 years of practice was a fundamental extension of the work. People have asked us over the last three years during the various iterations of this retrospective which parts either of us has worked on. In my view, that is the wrong way to approach it. Exhibition-making on architectural terms is a conversation that is entirely collaborative and expansive.

Koray Duman: From the start, I knew Paul was thinking deeply about how the exhibition design could support the narrative arc of over two decades of work, while also responding to these drastically different architectures. We began with The Geffen, which is enormous and warehouse-like, moving through it, placing things intuitively, almost by feel. Very quickly, a narrative started to emerge. He was interested in introducing some of the more intimate works within smaller settings, and we designed a sequence of quieter, enclosed rooms where viewers could have a one-to-one, almost private encounter with the work. But even within that intimacy, you sensed that there was a vast space waiting beyond. That shift happened suddenly, giving way to the main volume of the galleries. Paul was fascinated by the infrastructure of Hollywood, especially the architecture of movie production, and the site of the sound stage became a conceptual and spatial reference: its structure is designed to be built up and broken down easily, with no exterior skin, just exposed wood framing and a thin shell that creates the illusion of an interior. We wanted to push how the work connects to broader organized systems of meaning — sports, religion, politics — and the collective rituals that shape public life. A work like Cross Hall (2008), for instance, is a scaled-down recreation of the neoclassical hallway in the White House, often used as a backdrop for State of the Union addresses. It is a set, a surface made for television, and the viewer is positioned not just in front of it, but also behind it — revealing the mechanics of representation. That logic, already embedded in the work itself, was something we expanded into the exhibition as a whole — broader questions about the spaces that exist between façade and backstage, surface and structure.

PP: Right — the idea of the sound stage as an architectural typology offered us a compelling framework for not only thinking through broader social phenomena, but also for presenting work that moves across seemingly disparate media. We found we could get really nuanced, almost like jumping between dimensions, yet remain rooted in everyday experience. Ultimately, the project became a way to think about how space is constructed, both physically and conceptually.

Installation view, MCA Screen: Paul Pfeiffer, MCA Chicago. December 23, 2017–May 20, 2018. Photo: Nathan Keay, © MCA Chicago.

Paul Pfeiffer, Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse (09), 2004. Fujiflex digital C-print; 48 × 60 in. (121.9 × 152.4 cm). Collection of Alan Hergott and Curt Shepard. © Paul Pfeiffer. Courtesy of the artist; Paula Cooper Gallery, New York; carlier | gebauer, Berlin/Madrid; Perrotin; and Thomas Dane Gallery, London.

Something I returned to throughout the show was how the world of professional sports is presented as this sort of logical extension of the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth century advent of crowds — the introduction of the spectator, the mania of the masses. You experience the sensation of crowds in the show in either extremely removed ways, or you are completely embedded in it.

PP: The powerful thing when you participate in any kind of ceremony — be that in a church or a chapel or an arena — is that one loses themselves within that space’s sound. It causes a collapse. There is also immersion, moments to come in and out of, like at the end of a game. That is the primary opportunity of artists and architects working together, and why it makes sense right now — we exist in a hybrid space and must think beyond the inherited terms of either field.

How the sound/architecture paradigm is struck across the exhibition is interesting. The way that viewers walk in and out of the galleries often implicates them in a film of their own. In The Saints (2007), by the time the viewer reaches the small video at the end of the hall of the lone soccer player running on the field, they have already performed the same movement against the sonic backdrop.

PP: Right. There is no crowd, but the sound creates that. The fact that the MCA installation unfolds in a room that shares the qualities of a chapel is part of what makes the work so architecturally successful. It embeds the viewer.

KD: That is what you are always interested in, Paul — how one loses themselves in a crowd. When I was a child, I remember being forced to go into a mosque with my father. The experience of that kind of crowd is primarily through scent, which places you within a kind of empathy with the space, but also you can disappear in the sound.

Installation view, Paul Pfeiffer: Prologue to the Story of the Birth of Freedom, MCA Chicago, May 3–August 31, 2025. Photo: Bob. (Robert Chase Heishman + Robert Salazar).

Paul Pfeiffer, John 3:16, 2000. Standard-definition video (color, silent), 5.6-inch LCD monitor, and metal armature; 6 × 7 × 36 in. (15.2 × 17.8 × 91.4 cm); 2 minutes, 7 seconds. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of David Teiger. © Paul Pfeiffer. Courtesy of the artist; Paula Cooper Gallery, New York; carlier | gebauer, Berlin/Madrid; Perrotin; and Thomas Dane Gallery, London. Photo: Steven Probert.

Paul Pfeiffer, Live from Neverland (still), 2006. Two-channel digital video loop (color, sound) and monitor; dimensions variable; 10 minutes, 18 seconds.Courtesy of the artist. © Paul Pfeiffer. Courtesy of the artist; Paula Cooper Gallery, New York; carlier | gebauer, Berlin/Madrid; Perrotin; and Thomas Dane Gallery, London.

So much of that sound quality is how it reverberates off the built environment, right? Again, it has to do with the public spaces we inhabit.

PP: Totally, yet it feels like the political language we use to describe the public realm — ideas like the body politic or shared social space — do not fully account for the complexities of our present moment. It feels like there is a longing to return to a more stable past, whether that is a nostalgic or overly simplistic way of thinking, but what is more likely is that this idealized public field might have never existed. The work still insists on asking the question of how we might live together differently, even if we do not yet know what that looks like.

That is the inherent part of your speculative practice — inventing a past that would inform a potential present. I wanted to touch on how these moments linger in the work and in the exhibition design — and to talk about ghosts. The realms of culture and architecture coming back to either haunt or guide us.

KD: Public architecture is definitely haunting us. There was a great moment in the show at the MCA that happened last minute — I think it was Paul posed the question: what if you imposed an image [one of the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse (2000–ongoing)] onto the transparent façade of this brutalist building, one I might otherwise call borderline fascist? Juxtaposing an image of a very triumphant looking basketball player, who almost looks like Jesus, onto this kind of architecture immediately becomes criticism. The ghosts of buildings ask us to interrogate how we are engaging with the public, now.

PP: It makes me think about the idealistic dimension of architectural production. In some ways, raising the “ghost” of architecture feels ambiguous to me. Ghosts can be both good and bad — omens of sorts — and they often do not communicate directly. They are mute, or opaque. More like puzzles that emerge suddenly. They function like an unconscious mirror, revealing to us something about ourselves that we have forgotten. I appreciate what you said, Koray, about the brutalist building and the history it embodies, and it makes me think about the role of manipulation in different disciplines. In art discourse, for instance, there is often a taboo around manipulating an audience. We are trained to reject illusion — to expose the stretcher bar behind the canvas, to undermine the window-like illusion of painting — as a kind of ethical imperative to foster self-awareness. But architecture operates differently. Its entire nature is to shape experience, to condition behavior — the question is not whether you participate in manipulation; it is a given. But ultimately, this plasticity is deeply ambiguous. That ambiguity is what I keep returning to. The beauty of invoking ghosts through aesthetic terms is that they possess an essential muteness. Any of the figures in The Four Horsemen could be the figure of Christ, but they could also be the figure of a bound slave.

Do you think it is because that muteness allows projection of desire?

I think so, yes — it is neither utopian nor dystopian. It just is.

Paul Pfeiffer, Red Green Blue, 2022. Single-channel video (color, surround sound); dimensions variable; 31 minutes, 23 seconds. Courtesy of the artist and Paula Cooper Gallery. © Paul Pfeiffer. Courtesy of the artist and Paula Cooper Gallery, New York. Installation view: Red Green Blue, Paula Cooper Gallery, New York City. November 12, 2022–January 12, 2023. Photo: Steven Probert.