NICOLA VASSELL ON ROBERT IRWIN, EXPANDING THE CANON AND BRIDGING ART AND POP CULTURE

by Emmanuel Olunkwa

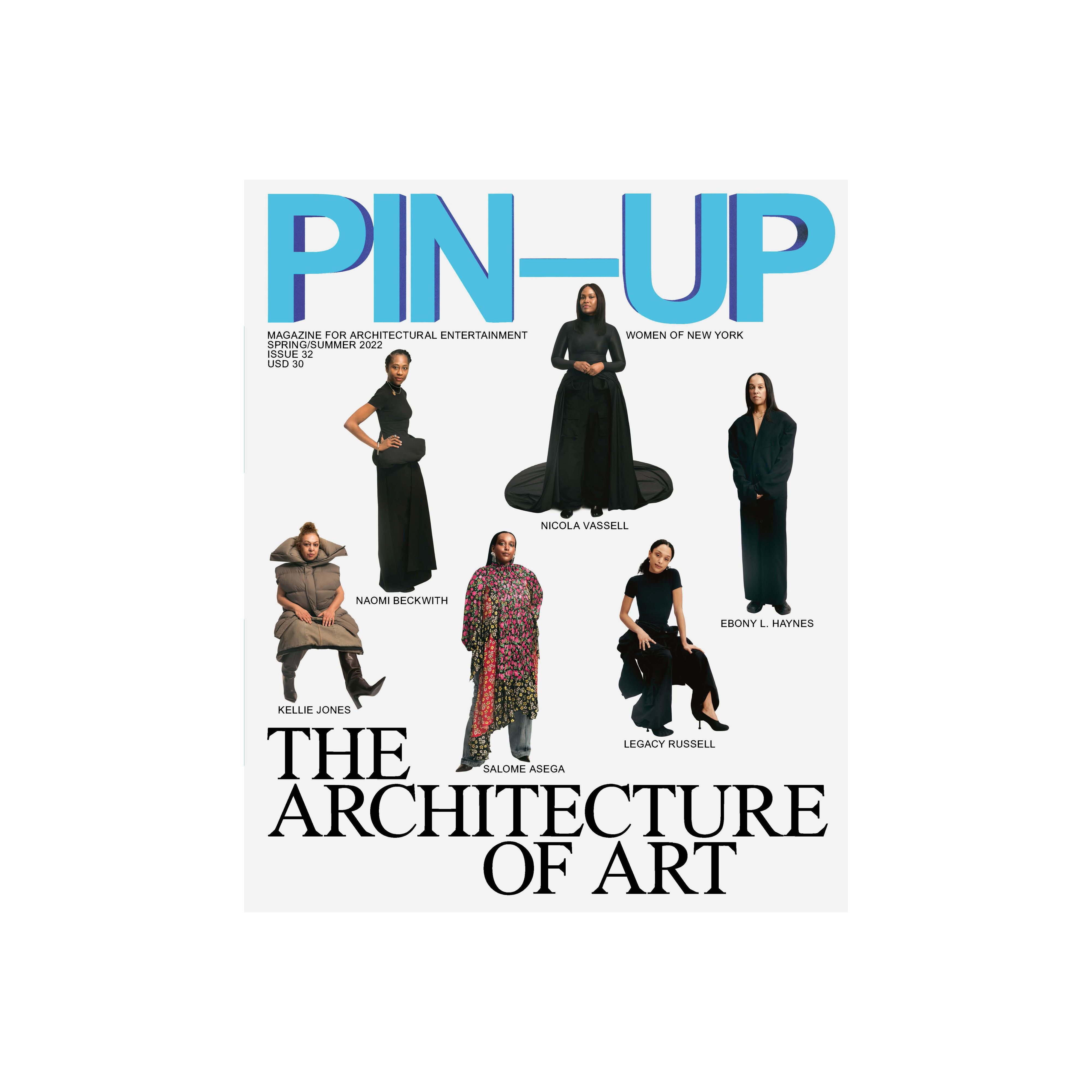

Nicola Vassell photographed by Caroline Tompkins for PIN–UP.

Nicola Vassell has a certain knack for extending her influence outwards, creating a ripple effect that starts in the art market’s center and ends in the annals of popular culture at its broadest. On the one hand she has held positions as director at both Deitch Projects and Pace, while on the other she consulted for the Fox show Empire, filling its scenes with works by artists such as Kerry James Marshall, Wangechi Mutu, and Kehinde Wiley. As a tastemaker and art adviser, Vassell also convinced rapper and record producer Swizz Beatz to purchase a Wiley painting of a Black man in green hoodie reclining in precisely the same manner as Auguste Clésinger’s 1847 Femme Piquée par un Serpent. Last year, Vassell set out on her most ambitious project yet, launching her very own gallery in Chelsea. Her first show in the eponymous space was a retrospective of work by Harlem-based, Detroit-born photographer Ming Smith, who showed shots taken between 1971 and 1998 featuring figures such as Sun Ra and Grace Jones. For the 2022 season, Vassell opened with another demonstration of her ability to collapse cultural worlds we tend to compartmentalize: musician Moses Sumney’s Blackalachia, a feature-length performance film set in North Carolina’s Blue Ridge Mountains in which Sumney explores the relationship between Black migration, bluegrass music, and Appalachia. Though always jumping lanes, Vassell remains committed to cross-disciplinary perspectives.

Emmanuel Olunkwa: Rather than working in an institutional context, you’re very much doing your own thing right now with Nicola Vassell Gallery, and historically, you’ve brought art into the realm of pop culture. How do you think about what you do?

Nicola Vassell: I think of myself very much as an arbiter. The artists I’m interested in push boundaries and make provocative work that challenge normative patterns of thinking. I work with artists outputting high quality work, even if it’s more of an indication of further greatness to come. So I’m really interested in giving those kinds of artists a platform, because they are the ones ready to tell stories about who we are at any given time.

Why did you decide to depart from working in art in a more traditional capacity?

I began my career 20 years ago as part of the downtown avant-garde circuit, so there was always room for experimentation, play, and curiosity there. It was that post-9/11 moment. And even though you know that New York never stays the same, I just had a feeling that the former hum of life would continue, but 9/11 cast a more drastically separate trajectory for the world than I had ever imagined. There was a kind of thrust of anxiety that needed to be measured and deciphered, and I think a lot of artists took that anxiety and tried to manifest it in their work. So many new systems were born out of the post-9/11 moment.

And after that period you went to Deitch and Pace.

I didn’t stay at Pace long, though it was enough time to get the blue chip education that I needed. I went there specifically to work with Robert Irwin, who was somebody I was really fascinated with conceptually. I thought so many of his ideas formed the basis of how one should look at life generally. And in a way that is my ethos: what I learn in art is really a prescription for life. It’s the thread that runs through everything that I do. But Irwin, of course, is fascinated by this idea of infinity and how perception is altered at any given moment. It really is a question of truth. It ties into the notion of how unstable truth is in a sense, because what is true at noon for this object is very different than what is true at two o’clock. He really pushed my thinking about what constitutes possibility.

What would you say you were looking for educationally?

I’m always looking for profundity, but in a simple manner. If you’re communicating through a complex framework, then sometimes the lesson can get lost. I love profundity that’s simple, because in a way that’s hardest.

What were you looking for when you first encountered art?

I came to art through fashion. They’re both about about imagination. It’s all about creative propulsion and seeing what one can design from the same prompts. Who is bold and bright enough to extract the singular thing from the same things we all see and experience?

And then how did you pivot to consulting?

After Pace, I went on to start Concept NV, my art consultancy and curatorial agency. I realized at a certain point it was time for me to move on from the gallery world. It was a process of letting go of what I had previously held as true in search of something new. This was when the importance of cultural conversation took root for me. In the end, I was really looking at cultural phenomena. I did that show Black Eye, for example, which forecasted so much of what we’re seeing now. We had 30 of the most interesting artists of that time who are now the bedrock of the Black art world, including Kerry James Marshall, Simone Leigh, Toyin Odutola, Gary Simmons, Jacolby Satterwhite, Xaviera Simmons, David Hammons, and Steve McQueen. It tapped a nerve, and it was really about Obama. It was about how the world had gone from not really understanding Blackness, and certainly not Black masculinity, and then the fact that the most powerful position in the world was held by a Black man. I was thinking about the conceptual implications of that.

What was some of the work that you were doing with your consultancy?

I worked a lot with Swizz Beatz. This was when Swizz and I decided to do our No Commission tour, which was our traveling art fair and music festival. This is when I stepped out of the center of the art world and reached more into the pop culture realm. And No Commission was such an interesting project for collectors and for me, as I got to form such a deep connection with Swizz. That was a multi-year project and at the same time, I worked with other clients and kept thinking about the future of the Black narrative in the art world.

What do you remember about that time now?

Ultimately, nothing changes in the art world. It’s fascinating to remember 15 years ago, when my peers and I were just kids, how we were running around Venice during the Biennale having a blast. Now they’re running institutions and curating pavilions. But you realize that people stay the same. It’s really a family that progresses forward.

How do you think about your programming at Nicola Vassell Gallery now in relation to how it might be perceived in the future?

It’s fascinating that we have hit a moment where there is this question of what constitutes history and what constitutes the future. I’ve been thinking a lot about that, about how to marry interesting stories. And it doesn’t have to be so heavy. It’s really just about artists who are thinking about the same things, whether it was 50 years ago, 20 years ago, right now, or in the near future. I’m fascinated by releasing some of those strictures that exist. These are all artists having the same conversation. It’s really that simple. It’s not asking for much, but it’s astonishing how infrequently people do it.

What are the ways in which you protect yourself in the work that you do?

I think understanding comes with time. I think the single most important rule that I abide by now is to just absolutely trust my instincts. It’s learning to trust implicitly, because that is a whole cosmic process. It’s the wisdom of the universe itself speaking to you, or through you at that point, and so many of us are so distracted that we learn how to quiet that noise.

How are you applying what you learned outside the context of art into the new frameworks you’re creating?

I think about the people who came before us, who for decades, generations, have just sat outside of these conversations. I am fascinated by this collective impulse to expand the canon. It’s almost like an unspoken unanimity of action that is taking place. It’s a force. It doesn’t have the power it has because it’s a singular effort. It’s an amalgamation of efforts, because every single one of us understands that the world has to change. It is changing, and how are we telling the story of that transformation? I think a lot about this collective spirit and how it is very much the quiet wind underneath the wings of change.

The WOMEN OF NEW YORK Special Cover of PIN–UP 32 is avaiable in a limited edition. Get your copy here.