Seneviratne House, Kandy, Sri Lanka, 1972, by Minnette de Silva. Gelatin silver prints courtesy Anuradha Mathur.

Woman carrying cement at the Capitol Complex, Chandigarh, India, in front of the Secretariat (1951–58) designed by Le Corbusier (Charles-Édouard Jeanneret, 1887–1965). 1956. Photograph: Ernst Scheidegger.

There’s a sleeper hit of an exhibition on view in New York featuring pioneering women, bioclimatic design, and models of futuristic mosques. It’s easy to miss, but can be found — for another week — on the third floor of New York’s Museum of Modern Art.

Every few years, the museum likes to take a thorough look at the legacy of Modernism in a little-explored— in terms of its architectural production — corner of the planet. Currently the focus is on four South Asian countries: India, Pakistan, Sri Lanka and Bangladesh. Under the mouthful of a title The Project of Independence: Architectures of Decolonization in South Asia, 1947-1985, the exhibition unites 200+ artifacts, including photographs, models and drawings, that examine the role modern architecture played in the subcontinent after liberation from Britain. It culminates a five-year investigation led by Martino Stierli, MoMA’s chief architecture curator, who organized the impressive survey with architectural historians Anoma Pieris and Sean Anderson and Evangelos Kotsioris.

Sunil Janah (Indian, 1918–2012). Industrial Documents. Untitled. 1940s–1960s. Gelatin silver print, 14 3/16 × 11 1/4 in. (36.00 × 28.50 cm). Courtesy Swaraj Art Archive.

It’s what MoMA does best: a rigorous revisionist deep-dive into a moment in history where Modernity promised more than it could ultimately deliver. The argument is that these young nations used architecture as an active agent to create the material infrastructure for their nascent societies. Specifically, the progressive governments in charge favored efficient, tectonically expressive buildings in exposed raw concrete for the schools, stadiums, stations and entire cities that had to be erected to project a new sense of forward-looking autonomy.

The idea of self-determination — that these countries could finally define for themselves how to govern, educate, house, and build — looms large over the exhibition. Indeed, freedom led to exhilarating inventiveness. The boundless optimism evident in many buildings is all the more poignant as it was borne out of unfathomable calamity: the 1947 partition into Hindu-majority India and Muslim Pakistan was accompanied by one of the largest, and most violent, mass migrations in human history (hundreds of thousands lost their lives). That architecture could be produced on pure faith in a better, sovereign, future despite such traumatic circumstances, is wondrous in itself, but that it could flourish with the panache that it did, is the exhibit’s great revelation.

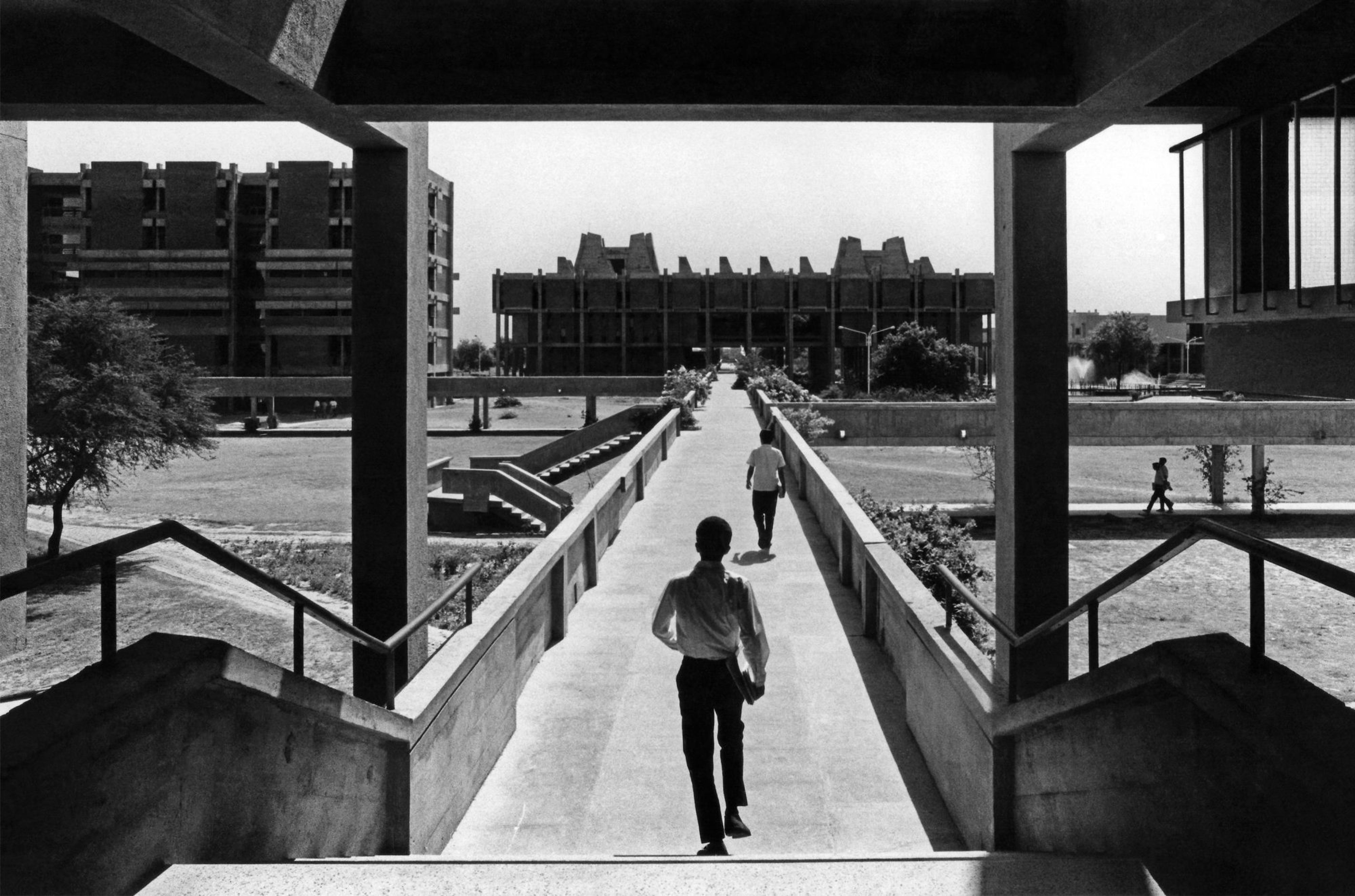

Indian Institute of Technology (IIT), Kanpur, India. 1959–66. Kanvinde & Rai (est. 1955). Architect: Achyut Kanvinde (1916–2002). Engineer: Shaukat Rai (1922–2003). Walkways linking major buildings. Photo courtesy Kanvinde Archives.

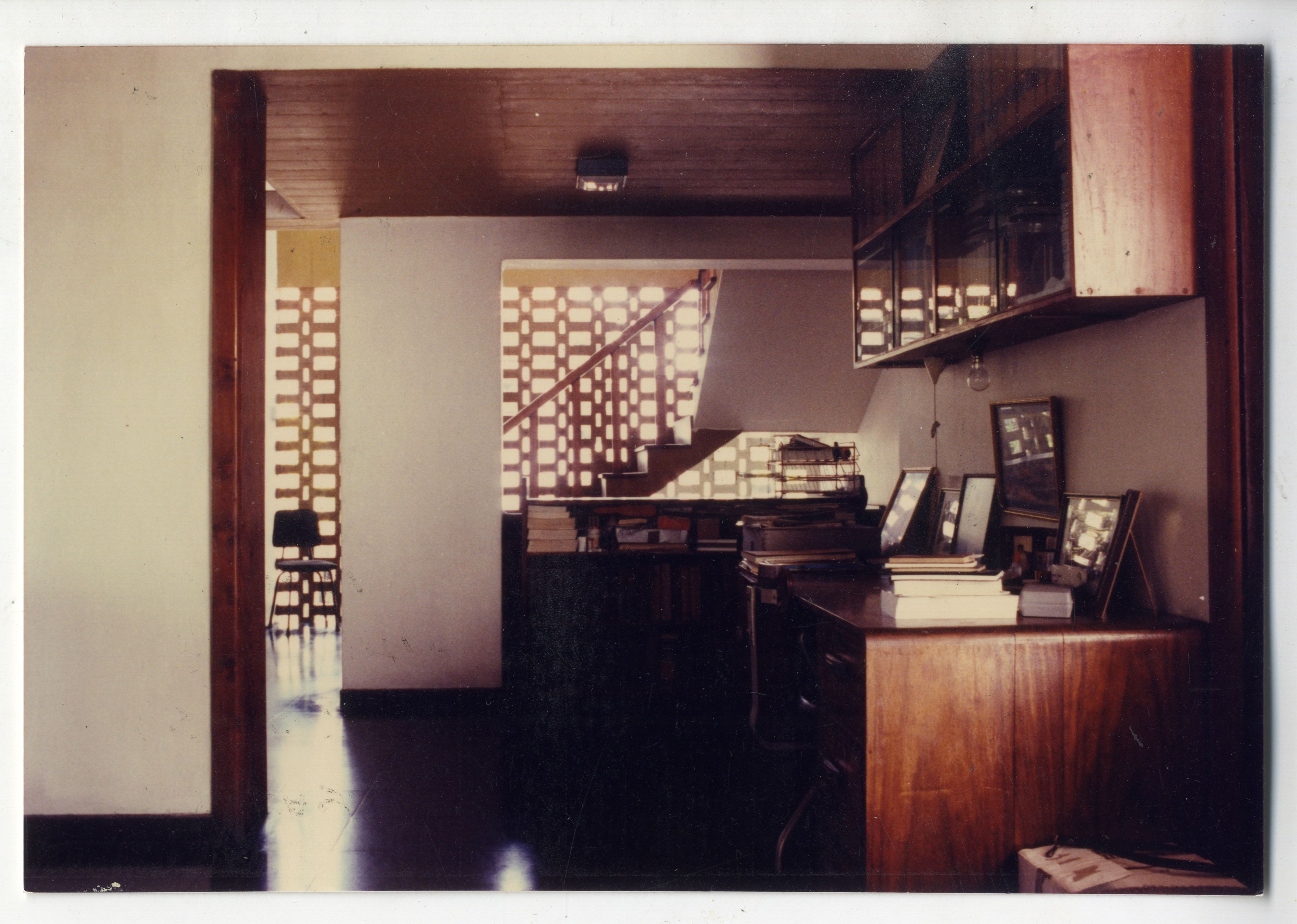

The Project of Independence’s undisputed stars are a hitherto unsung group of local architects that took the imported language of modernism and made something novel, thrillingly creative, and uniquely suited to local conditions. It is high time that talents like Achyut Kanvinde, Raj Rewal, Muzharul Islam, to list a few, are recognized alongside the more familiar names of (Pritzker-Prize winner) Balkrishna Doshi and Geoffrey Bawa. Some of the exhibition’s highlights are works by women. A small corner is dedicated to Minnette de Silva, Sri Lanka’s first female licensed architect and the country’s first woman architect to work with the lexicon of modernism. After studying at the Architectural Association School of Architecture in London, de Silva returned home and took on a number of residential commissions in which she masterfully blended the avant-garde volumes of European villas of the time with vernacular details and local materials such as jak and halmilla timber, woven palm and fire clay tiles.

Seneviratne House, Kandy, Sri Lanka, 1972, by Minnette de Silva. Gelatin silver prints courtesy Anuradha Mathur.

Seneviratne House, Kandy, Sri Lanka, 1972, by Minnette de Silva. Gelatin silver prints courtesy Anuradha Mathur.

Seneviratne House, Kandy, Sri Lanka, 1972, by Minnette de Silva. Gelatin silver prints courtesy Anuradha Mathur.

Seneviratne House, Kandy, Sri Lanka, 1972, by Minnette de Silva. Gelatin silver prints courtesy Anuradha Mathur.

One a more modest scale but no less generous, a low-income housing scheme designed in the early 1970s in Lahore by the great Yasmeen Lari was ahead of its time for producing a dense low-rise fabric that emulated the traditional streetscape of the old city rather than erasing it with generic, disconnected blocks. All units have access to a courtyard, carving out vital communal space for residents, while interlocking walkways, bridges and brick screens provide essential shade, ventilation, and privacy. (Besides Lari and a model of Anwar Said’s C-Type mosque for Islamabad, Pakistan is noticeably underrepresented in the exhibition.)

This being MoMA, the wealth and breadth of rare material assembled staggers, with treasures in each of six thematic subsections. A model for a sprawling structuralist village designed by Rewal for the 1982 Asian Games in New Delhi (it later became a coveted middle-class neighborhood) is a tour-de-force in how to keep a large-scale housing complex from being soullessly repetitive, incorporating pedestrian pathways and courts, careful shading and other elements that lend the development an organic sense of continuity and variation. Not evident at first, close inspection of the model reveals actual peppercorns were used to represent shrubs!

National Cooperative Development Corporation (NCDC) Office Building, New Delhi, India. 1978–80. Architect: Kuldip Singh (1934–2020). Engineer: Mahendra Raj (b. 1924). Exterior view. Photograph: Randhir Singh.

Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel Municipal Stadium, Ahmedabad, India. 1959–1966. Architect: Charles Correa (1930–2015). Engineer: Mahendra Raj (b. 1924). Exterior view. Photograph: Randhir Singh.

Kamalapur Railway Station, Dhaka, East Pakistan (Bangladesh). 1968. Louis Berger and Consulting Engineers (est. 1953). Daniel Dunham (1929–2000) and Robert Boughey (b. 1940). Exterior view. Photograph: Randhir Singh.

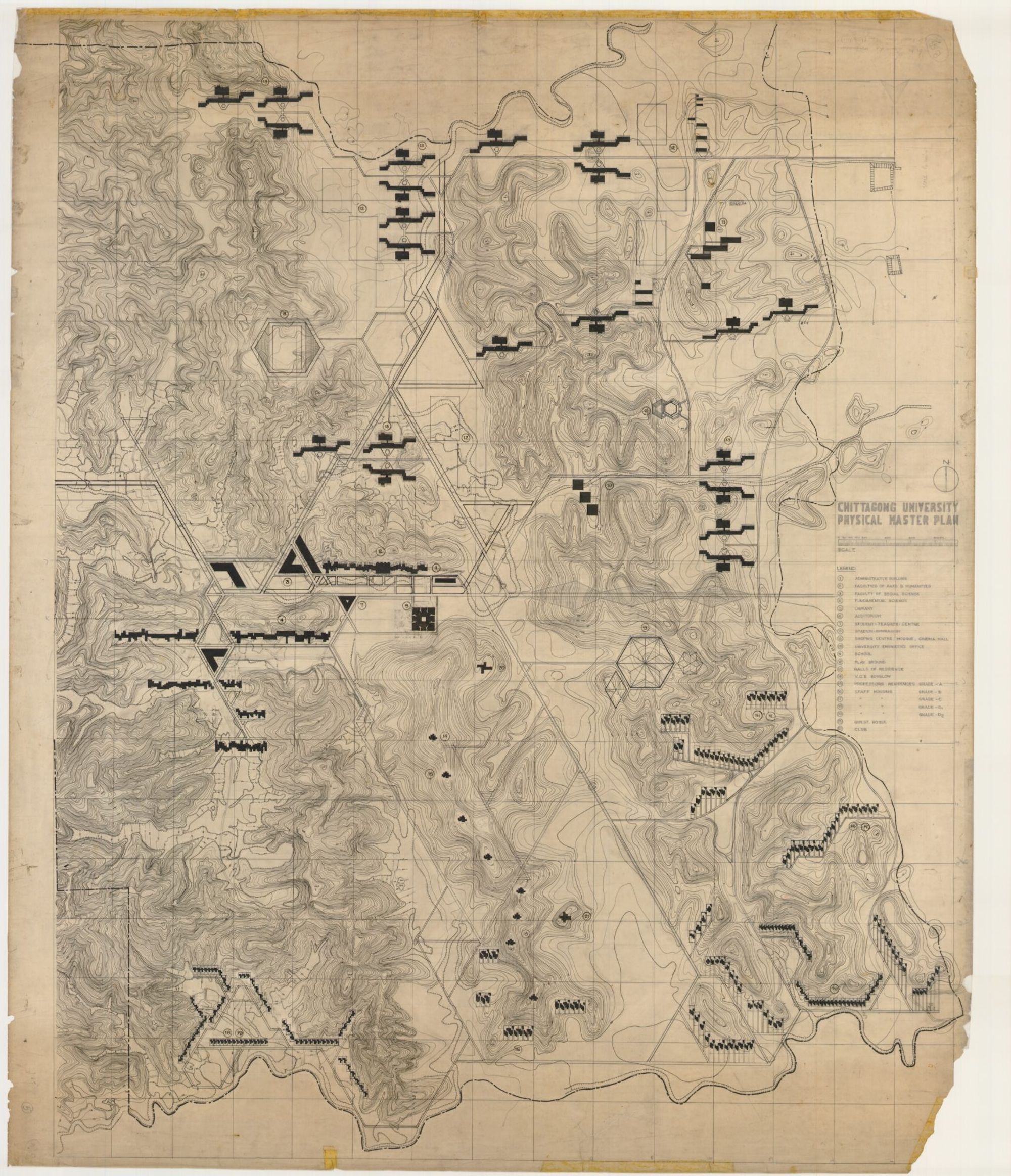

Similarly, only a closer look at a recent color photograph — by Randhir Singh, who was commissioned to shoot existing buildings to show how they’re still embraced by locals — reveals that a beautifully weathered structure in present-day Bangladesh is not abandoned, but in use for its original function. It is a dormitory at Chittagong University, designed by Islam in the late 1960s; if no windows can be seen it’s because the smart design encompassed semi-open spaces as cooling buffers, a concession to the area’s humid heat. The use of brick, too, makes abundant sense in a region known for its river deltas and clay deposits. Nearby, Islam’s gorgeous master plan for the university could be a Julie Mehretu painting. It’s also brilliantly sui generis and sensitive to the local topography, inserting clusters of bold, geometrically dissected volumes into the hilly terrain to create intimate terraced pockets and preserve ecosystems.

Chittagong University, Chittagong, East Pakistan (Bangladesh). 1965–71. Vastukalabid (est. 1964). Muzharul Islam (1923–2021). Master plan. Ink and pencil on paper. Muzharul Islam Archives.

Chittagong University, Chittagong, East Pakistan (Bangladesh). 1965–71. Vastukalabid (est. 1964). Muzharul Islam (1923–2021). Exterior view. Photograph: Randhir Singh.

Sadly, a lot of this excellence is subsumed in a lackluster, dark and somewhat confusing exhibition design, which feels more conducive to a desultory walk-through than to an intentional, focused viewing. A soberly minimalist museography is classic MoMA for these affairs, and the intention is surely to let the exhibited works shine against the austere backdrop, but here it risks dimming the inherent vibrancy of what’s on display. Kotsioris told me the galleries’ deep eggplant-and-gray walls were chosen to avoid referencing any of the countries included, a valid point, and the heavy curtain hiding the big glass expanse overlooking MoMA’s sculpture garden was necessary to protect the sensitive documents on view, but the combined effect is unnecessarily gloomy. It doesn’t help that a passage from a set of elevators to the rest of the expanded museum runs right through the exhibition. I witnessed several visitors ambling into The Project of Independence through this ‘back entrance’ not knowing what they were seeing and with little incentive, by means of context, to engage with it. No one could blame them.

Installation view, The Project of Independence: Architectures of Decolonization in South Asia, 1947–1985, on view at The Museum of Modern Art, New York from February 20, 2022, through July 2, 2022. Photo: David Almeida.

Installation view, The Project of Independence: Architectures of Decolonization in South Asia, 1947–1985, on view at The Museum of Modern Art, New York from February 20, 2022, through July 2, 2022. Photo: David Almeida.

Fortunately a hefty catalog makes up for the exhibition’s weaker points, offering a balanced, cohesive and intricate gesamt-view that will be useful to a wide audience for a long time. Rather than replicate the exhibition in a book, the curators introduce an exhaustive and handsomely illustrated collection of scholarly yet accessible, heavily footnoted texts (several authored by a board of regional experts) that contextualize the temporary show with facts, explanations and anecdotes. There are mini-dossiers for the most significant projects, while the lucid essays cover subjects left out in the galleries, such as house design and preservation (many featured buildings are endangered or already lost). The subcontinent’s unique labor and climate conditions emerge as decisive factors that give its modernist buildings their rich textured quality.

Lastly, it has to be noted that this is a region of over 1.5 billion inhabitants still rife with economic disparity and religious conflict; parts of it are frequently on the verge of humanitarian and environmental disaster. Of course there’s also prosperity, untold cultural wealth, ample natural and human potential, and robust homegrown academic scholarship. These are paired with surges of nationalism, political instability and crippling bureaucracy. Even without an intervening pandemic, foraging the area for the crowning achievements of a four-decade span of public and private construction that began almost 70 years ago would have been a valiant endeavor.