MICHAEL GRAVES’S TOP 10

Michael Graves's versatile oeuvre from everyday objects such as the now iconic (and oft-copied) tea kettle for ALESSI to iconic examples of Postmodern architecture. PIN–UP pays homage to the revered (and sometimes maligned) architect, artist, and designer with a TOP TEN of some of his most outstanding projects.

1—HANSELMANN HOUSE

Constructed between 1967 and 1971 in Fort Wayne, Indiana, Graves’s Hanselmann House was his first architectural commission, and was designed for his high school friends, Jay and Lois Hanselmann. Ostensibly influenced by Le Corbusier’s explorations of geometric compositions, and predating Peter Eisenman’s House VI by a nose, the Hanselmann House shares something of his more conceptually uncompromising colleague’s formal rigor: the house and the space immediately in front of it are a double square in plan and a double cube in volume, a nod to the unsmiling post-functionalism that was all the rage at the time. However, the irrepressible whimsy that would come to define Graves’s career is already present in the form of a mural that the architect hand-painted on the house’s interior, meant to serve as a kind of imaginary extension of the natural landscape.

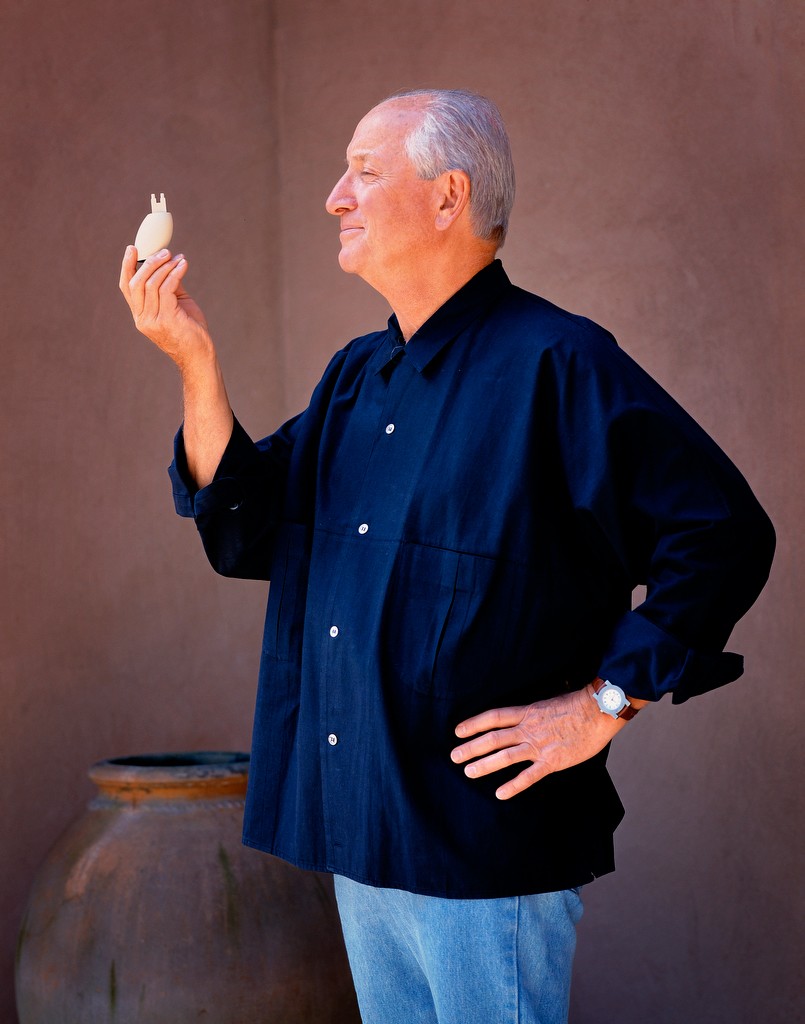

2—ALESSI KETTLE 9093

Introduced in 1985, Graves’s cheerful stainless steel kettle for ALESSI, with its cherry red, bird-shaped whistle, remains perhaps the most emblematic example of the architect’s winningest skill: his ability to combine great design with mass production methods that appeal to a broad audience. The 9093 combines aesthetic elements of art deco, pop art, and the cartoons of Tex Avery, without forgetting functionality. The kettle is emblazoned with red buttons on its bottom surface to signify heat, while the ergonomic contours of its perennially-cool-to-the-touch blue handle would later be giddily co-opted by the designers of sex toys. The little bird at the tip of the spout dutifully sings its peculiar, insistent tune when the water within has reached its boiling point.

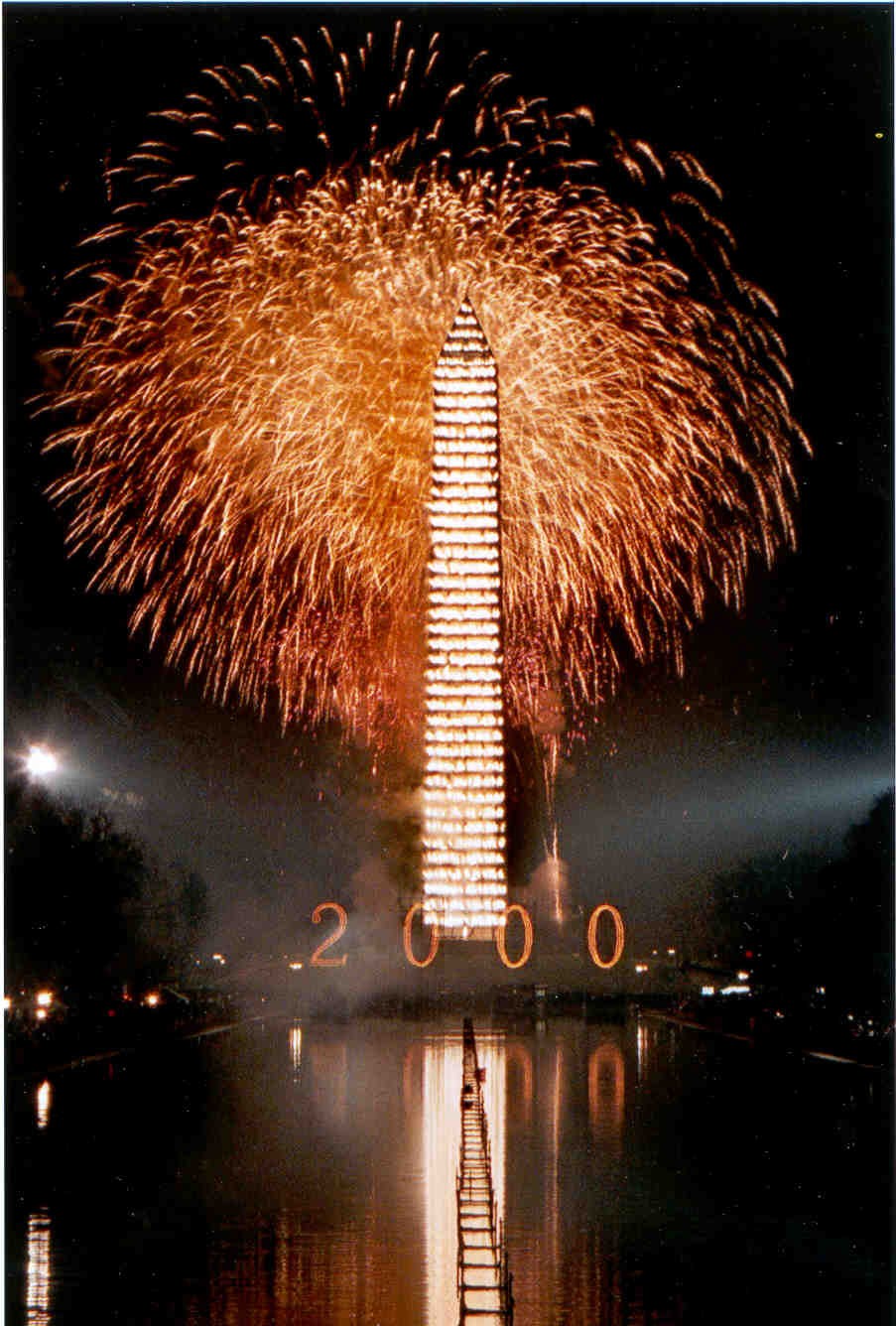

3—THE WASHINGTON MONUMENT RESTORATION

Graves was charged with a project of plain patriotic significance: he was to design a scaffold for the Washington Monument while it underwent restoration. Commissioned by a public-private partnership between the National Park Service and Target Stores and undertaken between 1998 and 2000, Graves designed both the scaffolding and the interior observation and exhibit levels, so the monument, much beloved of both American citizens and foreign visitors, could retain its proud status on the national mall even as much-need repairs were undertaken. The Graves-designed scaffolding was lit from within with hundred of lights, imparting a gentle, elegant glow to the national treasure. Additionally, the architect designed a blue screen net patterned to resemble the icon’s stone block pattern, as well as its general shape.

4—UNITED STATES POST OFFICE

Designed by Graves in 1996, the Post Office of the Disney-controlled, master-planned community of Celebration, Florida, stands next to its Town Hall, which itself was designed by Philip Johnson. Both architects chose to work in a Greek revival style. Graves’s post office employs a simple massing composed of two parts: a rotunda and rectangular block. Graves sought to lend the building a character and institutional presence that would both respect the traditional typology of the post office as well as its surrounding Floridian context. Although Graves’s building is small, it plays an important civic role in the community in which it stands. Oriented around a formal massing incorporating a loggia, coloration and materials that are all typical of The Sunshine State, the Celebration post office is marked by Graves’s signature use of grey, blue and terra cotta.

5—TELEPHONE FOR TARGET

So impressed were Target executives with Graves’s design for the scaffolding of the Washington Monument restoration that they asked the architect to design everyday objects sold at Target stores. With its fresh but familiar, happily bulbous contours, Graves’s iconic design for a telephone was the 2000 inauguration of a mutually beneficial collaboration. Target termed it “the democratization of design,” and indeed it was: even the architect had to purchase his own, newly mass-produced products, albeit at a modest of discount of ten percent.

6—THE PORTLAND BUILDING

The first substantial building rendered in the postmodern style, Graves’s 1982 Portland Building, erected in the city of the same name, is a good example of the architect’s controversial prime period, which was marked by a panoply of color, paradox, and a witty hybrid of references. The winner of a public competition, so controversial was Graves’s winning design that a second competition was declared, but the architect won again, on the basis of both style and cost-effectiveness. Graves’s design is formally notable for its stylized columns, wildly oversized keystone, and allegorical statue. But morphology and mannerism are only half the story: the Portland building is also an early example of passive cooling, and is outfitted with a rooftop apparatus to assist with heating, cooling and stormwater runoff. After much debate, in 2011 the Portland Building was added to the National Register of Historic Places.

7—WALT DISNEY DOLPHIN HOTEL

The Dolphin, so called because of the 56 foot-tall Dolphin statues that straddle each corner of the building’s main mass, was designed by Graves in 1990 at Disney’s Epcot Resort near Orlando, Florida. The Dolphin is the sister of the nearby Walt Disney World Swan, also designed by Graves. For the design of his dolphins, Graves relied on figures from the Triton Fountain in Rome, designed by Baroque master Gian Lorenzo Bernini in the 17th century. The main mass of Graves’s hotel is an enormous Platonic pyramid rendered in a dusky shade of coral. The architect concocted an elaborate, Atlantis-like narrative around the building, without doubt a fitting flourish for this essential example of what would come to be known as “entertainment architecture.” Nightly rates start at $165.

8—MIRAMAR RESORT

The Miramar, completed in 1995 in El Gouna, Egypt, is dramatically sited on the Red Sea, and designed to maximize water views (with the help of a few carefully master-planned canals and lagoons). Graves employed a vernacular of traditional Egyptian construction for his resort: brick vaults and domed ceilings help the visitor feel at home, while dramatic columns impart a sense of excitements and inverted pyramids ensure things don’t get too tiresomely historical. What’s even less traditional? The clever construction methods that helped Graves achieve his formal aims: the architect pre-engineered the finish of the resort’s exteriors, using a mixture of gypsum and pigment which he betted would weather quickly. Sure enough, within three years the facade had taken on the sun-faded, dusky tones the architect had aimed to achieve.

9—CASTALIA

Graves’s Castalia is one of the tallest buildings in The Hague, Netherlands. Erected in 1998, it is the city’s first building to stand taller than 330 feet, and houses the Dutch Ministry of Health, Welfare, and Sport. Graves accepted a uniquely challenging commission, for Castalia is not a pure ground-up design. Rather, it is an extrapolation of the carcass of Jan Lucas’s 1967 Transitorium, stripped to the skeleton and then rebuilt, re-clad, and expanded vertically with two gabled roofs over 100 feet in height. Those distinctive roofs, inspired by the steep gables of traditional Dutch residential architecture, were creatively nicknamed “Haagse Tieten” (Hague’s Tits) by the city’s sophisticated citizens, and serve no greater purpose than to memorably punctuate an otherwise milquetoast skyline. The building has recently been endowed with Dutch national landmark status.

10—DRIVE MEDICAL CLAMP RAIL TUB

All too often, design is born of personal necessity: such was the case with Michael Graves’s foray into the design of medical equipment, undertaken after in 2003 the architect was stricken with a spinal cord infection that left him paralyzed from the waist down. Drawing upon the same blue-grey color familiar from many of his existing industrial design products, and accented with a hot signature hue (“Orange activates,” the architect asserts), Graves’ collection of bath products, such as the medical clamp rail for Drive, strike the perfect balance between beauty and functionality, and are easy to grasp for most people, in both the literal and figurative sense.