Michael E. Reynolds photographed by Luke Abby for PIN–UP 36.

Michael E. Reynolds photographed by Luke Abby for PIN–UP 36.

Michael E. Reynolds photographed by Luke Abby for PIN–UP 36.

Fifty-three years ago, Michael E. Reynolds completed the world’s first recycled-beer-can house in the New Mexico desert. This radical gesture, made by a 26-year-old just out of architecture school, came decades before the terms upcycling, green architecture, reuse, and sustainability entered mainstream architectural discourse. While Reynolds’s breakthrough creation made him famous, responses varied: a novelty joke for the general media, the Beer Can House was derided as a disgrace by the architecture profession and hailed as visionary by the budding environmental movement. Like Emilio Ambaz’s Casa de Retiro or Lacaton & Vassal’s Maison Latapie, Reynolds’s first building was a manifesto, offering a glimpse of the philosophies that would guide his life’s work. In the late 1970s, the Beer Can House was presented in an exhibition at the Louvre titled Urbanism Architecture 2, and last year it was presented at MoMA. In the over five decades in between, Reynolds has designed and built hundreds of elaborate, mystical sustainable homes all over the world. Like his biblical role model Noah, Reynolds builds arks to rescue people from drowning in a toxic world, refining his goals of autonomous living with each house — or Earthship, as he calls them — that he constructs. Since he also teaches others how to build their own environmentally-conscious homes, and they in turn spread the word, a substantial alternative community has developed. Now the central figure in a building movement he calls biotecture, the 79-year-old has set himself one final goal: rolling out his off-grid machines-for-living at an affordable price to a mainstream market. To do this, the man who prized his independence above all else has burdened himself with becoming a real estate developer, designing and building a New Mexico Earthship community named Greater World. For the venture to succeed, he needed to resolve the question of how to build with recycled materials— especially rubber tires — in a systematic and repeatable manner. With 100 homes now completed, Greater World proves that Reynolds’s vision is not just a dream for a chosen few but a potential solution that could facilitate a livable future for us all.

In 2007, Michael E. Reynolds was granted a five-year permit to build without any code enforcement or regulation. Reynolds and his team were in the process of building EVE (Earthship Village Ecologies) when the permit expired, and construction was forced to halt. Today, it’s used to grow vegetables. Photographed by Luke Abby for PIN–UP 36.

Michael Bullock: I’m excited to learn more about Greater World.

Michael E. Reynolds: Well, we’re in the final years of developing a 640-acre subdivision for off-grid, sustainable, autonomous homes. We’ve been building like this for over 50 years. We have the vessel— we call it an Earthship. It takes care of people, it’s autonomous, and it addresses what we think are the six most important elements for human survival: comfortable shelter, water, electricity, food, sewage containment and treatment, and the reuse of garbage. We think that those six things must be built into every building and home so that people can be absolutely autonomous from the grid and from the dogmas that don’t seem to be working too well all over the world right now.

After 50 years of building custom homes, are you finally ready for the assembly line?

We want to get this vessel mass-produced and available to as many people as possible. We’re only building on 320 acres of the 640 — the rest is common green space for animals, birds, and creatures that were already here. We’re building 130 homes on those 320 acres, and 100 of them are already built. I’m working on three right now. The buildings are quite far apart, which allows animals to carry on roaming and doing whatever they did before we came. The subdivision has been the forum for us to develop this concept and, in that respect, it has been successful. Now we have a model we call Refuge, a two-bedroom, two-bath autonomous home that can be built off-grid all over the world.

Is Refuge much more modest than other Earthships you’ve built?

Yes. If you think about it in terms of the automobile industry, the cars that sell the most are the modestly priced Toyota Corollas. We want to make autonomous housing modestly priced relative to other housing. You can find tires all over the planet, so it’s easy to build these houses anywhere and address the same six points. If somebody wants one, they just come and buy one. We don’t want to have to take them through getting a permit, hiring an architect, and building it themselves, even if that’s perfectly doable — we do it with our academies and our intern programs. But over the years we’ve found that only about five percent of the people in the developed world are do it yourself-ers who want to build their own home. The other 95 percent doesn’t want to spend three or four years of their life on that. It’s just like how you go into a BMW dealership, and 45 minutes later you walk out with the keys to a BMW on lease. We want that to be the case with autonomous housing— after one hour in the office you leave with the keys to an autonomous building and you go on about your life.

The Phoenix (2005–07) is a model of sustainable luxury and whimsy nestled in northern New Mexico’s Sangre de Cristo Mountains. The 5,300-square-foot castle’s living room features a waterfall that pours over a built-in gas fireplace. All water used in the home is caught from the sky and an edible garden and fish pond are both beautiful and purposeful, recycling gray and black water. Photographed by Luke Abby for PIN–UP 36.

And you probably already collaborate with that five percent anyway.

We have been for 50 years, and it’s working. But we want this to be made available to everyone on the planet who wants it, because there are so many issues with conventional housing and the dogma surrounding it. In storms in Texas, Arkansas, or Oklahoma, let’s say, the power lines go down, so people don’t have electricity, and the tornadoes blow their houses away. The maintenance that conventional housing requires is ridiculous. Our buildings won’t blow away. They’re fortresses. If power lines go down, or the water gets contaminated or short, we don’t even know it. If the grocery shelves get empty, we don’t even know it, because we can grow food in our house. That does require you to be vegetarian or vegan, but that’s worth doing because it’s better for you than animal products. We’re getting into what it takes to keep humanity healthy and alive off all the grids.

How much does it cost to purchase a Refuge Model Earthship?

We have a two-bedroom, two-bath Refuge on a 3-acre lot that is available for 550,000 dollars. That’s the typical price of a two-bedroom, two-bath home, only this one has no utility bill whatsoever, which saves you at least 1,000 dollars per month. That was our first Refuge, so it’s just being developed. We hope the next ones we build will be 100,000 dollars cheaper because we’re going to start making them en masse. We want to get it down to around 450,000 dollars for a two-bedroom, two-bath Refuge that can be built anywhere, and we’re pretty sure we can do that. The Refuge is our most affordable Earthship, and we have three other models — Unity, Encounter, and Global. We’ve built them in France, Alberta, Canada, and Puerto Rico. They’re more like Lexuses, but we want to put out a Corolla.

So you’ve seduced the world with your flagship designs, and now you’re pioneering something for everyone.

Yes. How long did Henry Ford work on the Model Tbefore it was right? To make it available, he invented the assembly-line method of construction. Now we’ve got to invent a way to make these Refuge Earthships appear all over the planet. And we’re building them ourselves, of course, but we’re also teaching people how to build them: students, academies, interns, ex-employees. We’re not really franchising it like McDonald’s, because we don’t want anything to inhibit people from doing this. We want to make it easy for people, because housing as we know it now is one of the top three destroyers of the planet, and it’s still vulnerable and unreliable.

Photographed by Luke Abby for PIN–UP 36.

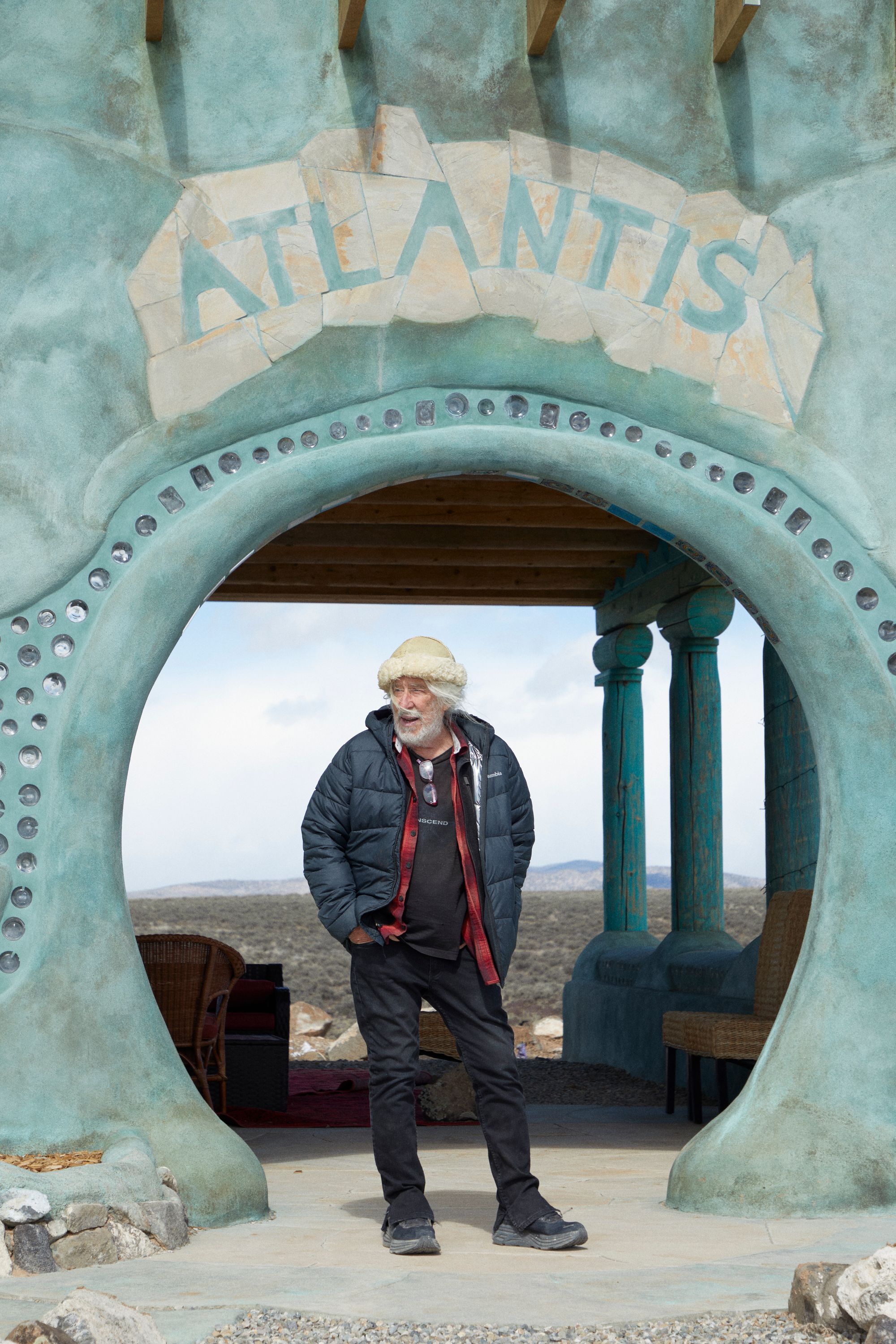

Michael E. Reynolds outside Atlantis, completed in 2023, one of his most embellished Earthships, which he likens to a piece of sculpture. On one end of the building, Reynolds built a white onion dome — an eight-room birdhouse —made from refrigerator and washing machine panels to makeup for the few trees in the desert for our feathered friends. Photographed by Luke Abby for PIN–UP 36.

Throughout your career you’ve been celebrated by some of the most revered institutions, but you’ve also been derided by local politicians, the building industry, and the architecture establishment. Now that the mainstream seems to have accepted that climate change is destroying us, do government officials finally understand and support your vision?

From my very first tire house, when even my crew thought I was an idiot, it’s gotten better and better over five decades. With global warming and population explosion, the world’s been going downhill while we’re going up with the quality of these things. We’re in the right place at the right time. But it’s been a hard road. These are not conventional buildings, and anything that’s not conventional is going to be a difficult sell. Now we’re at the point where everybody understands that we’ve got to do something different.

How do you standardize and mass-produce a house built from recycled materials?

A typical Refuge Earthship is made from about 50% recycled materials — tires, cans, bottles, cardboard, even panels from fridges and washing machines. And then there’s 50% conventional materials — lumber, glass, concrete, as well as components like doors, window boxes, transoms, cabinets. What we’re doing is looking at manufacturing all these components, delivering them to the site, and then with local people, you know, sometimes 50 at a time, pounding up the tires on site and assembling the building on the tires. We built a three-bedroom, two-bath, global model Earthship, in Alberta, Canada in five weeks.

Many students of the Earthship Biotecture Academy have stayed in this building named the Hive while completing training programs in New Mexico on how to build and maintain Earthships. Originally completed in 1996, additions were later made in 2004, and today the floor plan includes a kitchen, two bathrooms, and a lofted nook for sleeping. Photographed by Luke Abby for PIN–UP.

Photographed by Luke Abby for PIN–UP 36.

Photographed by Luke Abby for PIN–UP 36.

Photographed by Luke Abby for PIN–UP 36.

Can you walk me through how the passive heating and cooling systems work?

Everybody knows what a Thermos bottle is — an insulated container. The insulation is key: if you pour hot soup into it, the insulation keeps it hot all day long. Well, imagine you make a little bubble inside the soup, and that’s where you live. You live inside the thermal mass of the soup that itself is inside insulation. That’s what an Earthship is. It’s insulation on the outside of tire mass walls, which is the soup, and your living space is inside the soup. Take your Thermos bottle, lay it down horizontally, slice off one side, and orient it toward the sun to heat the soup — that’s also your Earthship, which will stay warm for two or three days in poor weather because of the insulation. The Earthships store heat in their walls — that’s why there are such thick tires there. In a heatwave, we cool them by bringing tubes through the northern, buried side of the building, and we have transoms on the south side that open up and let the heat escape, which creates a suction through the tubes.

What’s the average temperature inside a Refuge?

Around 70 degrees Fahrenheit year-round without fuel. The roof catches water and recycles it four times — that’s what we’re going to have to do on a planet that’s running out of drinking water. Refuges generate their own electricity from sun and wind, and they contain and treat their own sewage and grow food in what we call botanical cells. And of course they’re made with 50% garbage. What we’re saying is that this is an autonomous living model that’s much less vulnerable than a five-million-dollar wood frame house that’s going to blow away in the next tornado and not work if the power lines go down. I’m not saying get rid of all the power lines — I’m saying let them be your backup. Do not depend on any kind of grid, because the grid is political. It’s dependent on a good economy, on global warming getting under control. The grid is vulnerable. In an Earthship, the only vulnerability you have is if they drop an atomic bomb on top of you.

Construction of The Phoenix, New Mexico. Build date: 2005 - 2007. Image courtesy of Michael E. Reynolds.

Great pitch. I’m ready to buy one. These buildings have come about through years of experimenting on your own living spaces. Who were your role models when you started out?

Well, the only human I ever really looked at as a role model is Noah, who built a giant boat out in the middle of the desert, with hundreds of people telling him he was a flamin’ idiot the whole time. He was driven by a truth he was made aware of. Well, I have looked out into the world, and I’ve seen the only truth is that there is no truth in our political, spiritual, or religious regimes. But there is truth in the sun. It will tell you, “You stay naked in the Sahara Desert for five days, and I’ll kill you.” Or, “You build an Earthship facing south and I’ll make you warm.” These buildings encounter the sun, the wind, and the physics and biology of the planet to provide sustenance for people. I call these phenomena “unarguable.” Who is going to argue with gravity? Well, jump out of the goddamn airplane and see how you can argue with gravity. The Earthship is built on the concept of “unarguables.” You can argue with politicians about nuclear or coal-fired power, but you can’t argue with the sun or with gravity.

You started building in the 70s, but you started calling them Earthships in 1988. What was the evolution?

I wasn’t on a course or a path. I was in the deserts in New Mexico taking care of myself. I learned these things to take care of myself — I had no plans of being an entrepreneur or inventing a solution for anything. I just said, “Hell, the world is a mess, I can at least make my life not a mess.” Forty years ago I set myself up autonomously, but, when other people wanted it, I had to take on clients, building inspectors, lawyers, and realtors. That was not a fun process. I was building these things out of garbage, containing sewage — the permitting offices and engineers thought of me as a turd in the punchbowl. I was like the ugly duckling. And as the world got in worse shape, and we got better at building, Earthships have turned into the swan. If I bring anybody on a cold winter night into one of our newer Earthships, they’re just blown away. You should see what people write in the Airbnb guest books. Whereas a few decades ago, people were damning me — “What is this hippie doing out in the desert, building with garbage and playing with sewage?” I lost my architect’s license in New Mexico due to breaking every rule in the book. The first time I told an engineer I was going to make a building out of beer cans, he got red in the face and stormed out of the bar we were drinking at. He said I was a disgrace to the architectural community.

Where does that anger come from?

These people have strived to get their architectural credentials. Those credentials are dogma, and I’m undermining them. Losing my own credentials in New Mexico allowed me to move faster into our autonomous-building method. I don’t give a damn if it’s architecture or not — I call it biotecture. I do have my architectural license in Nevada, Colorado, Arizona, Puerto Rico, New York, Canada, and other places, but I never reapplied in New Mexico because I don’t need to be an architect to do what I’m doing. Typical architects are making flamboyant pieces of beautiful sculpture that cost 40,000 dollars a month to operate in utilities, which certainly isn’t sustainable or autonomous. If that’s what architecture is, I want no part in it. I want a structure and a vessel that will take care of people and the planet.

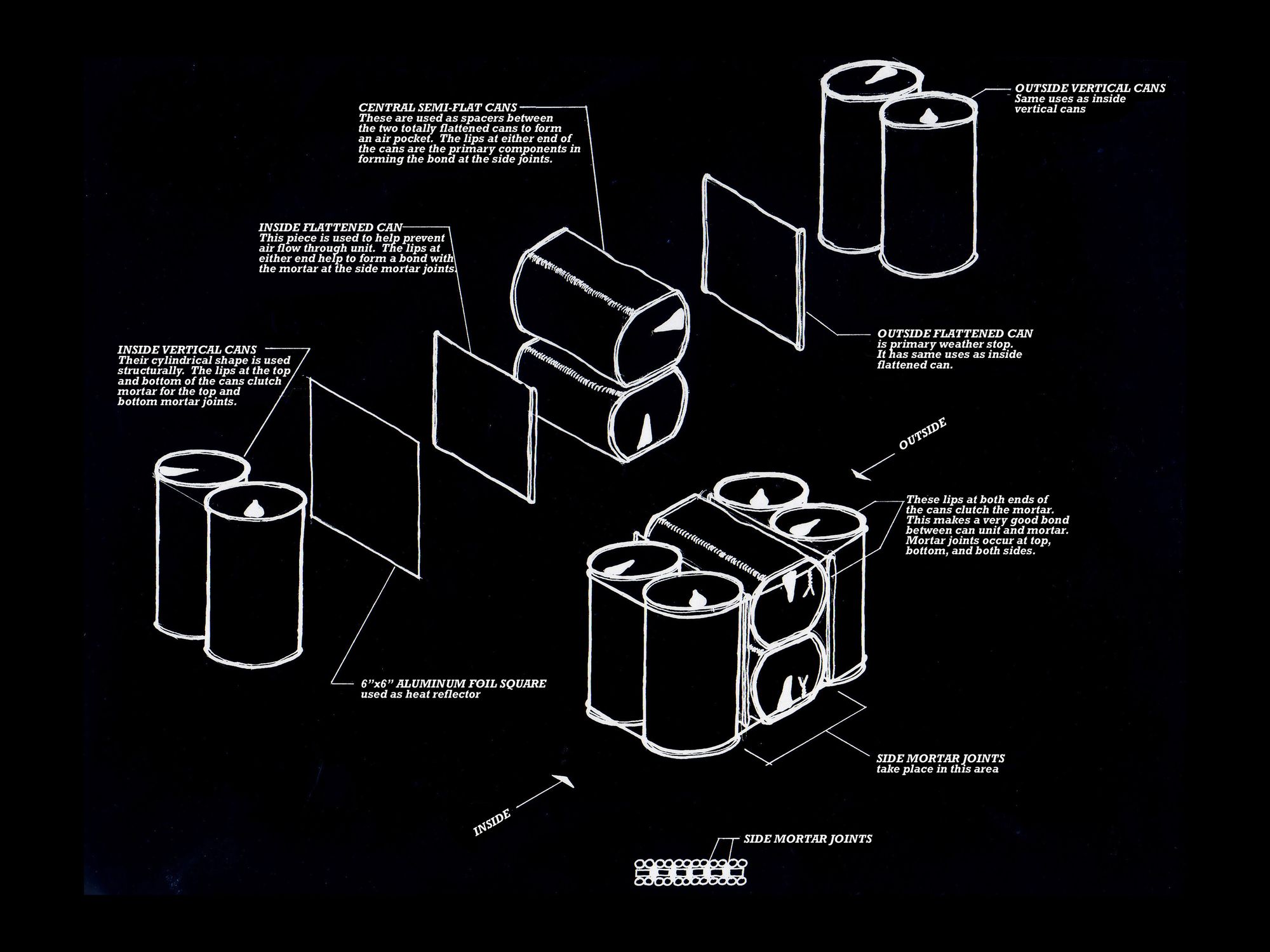

Beer can block diagram. Image courtesy of Michael E. Reynolds.

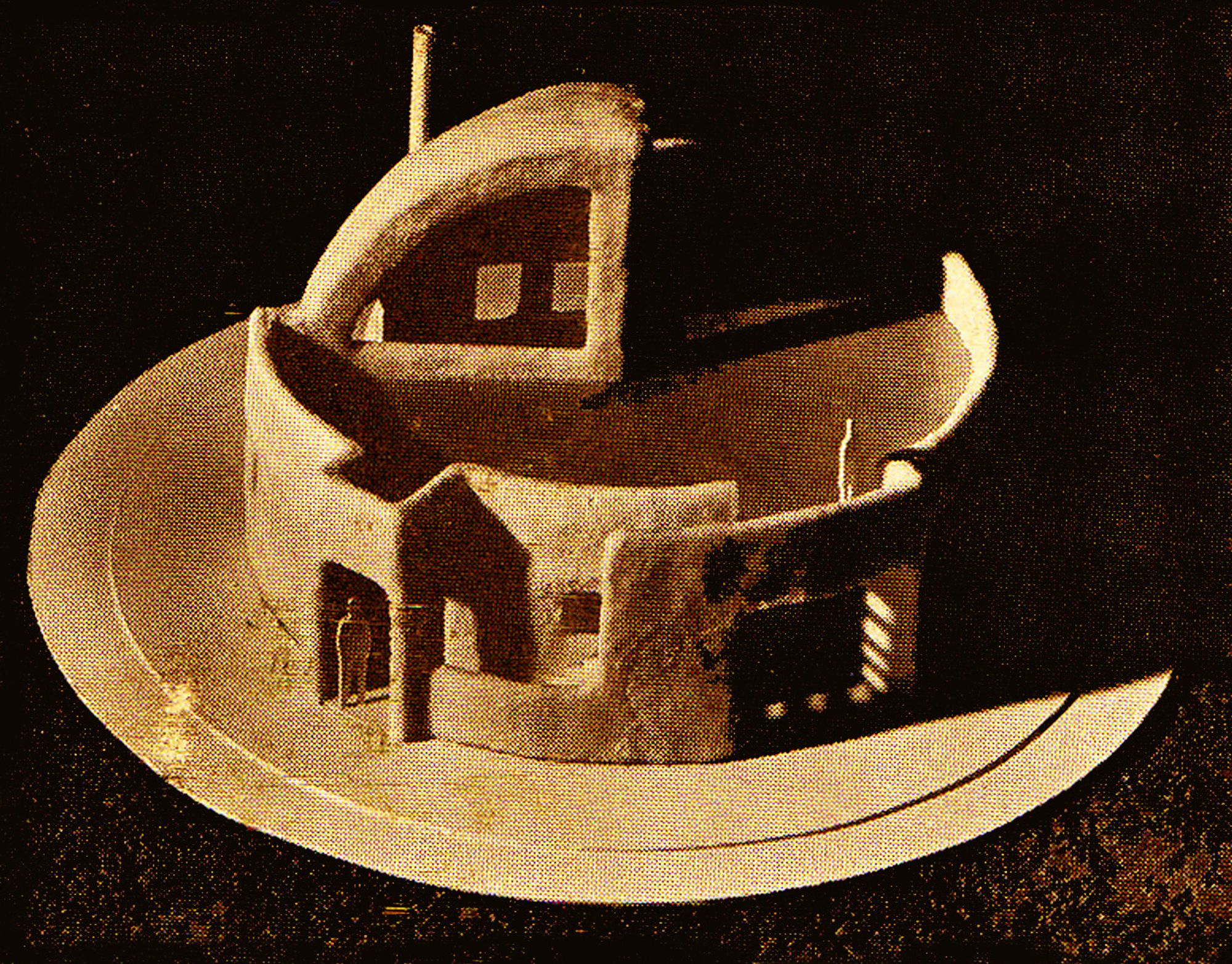

Model for Thumb House (1971). Image © Michael E. Reynolds.

Michael E. Reynolds photographed in an Earthship by Luke Abby for PIN–UP 36.

I recently interviewed Emilio Ambasz, who explained the role of mysticism in his practice — letting visions come to him. I thought about this when I read about a vision you had in which you described being visited by four wizards.

I used to do a thing where I would strap myself in a coffer up on top of a pyramid and gaze at the full moon once a month as it crossed the southern sky. When it would get perfectly aligned — the full moon is just reflecting the sun — it just literally went into my skull and burned my brains out. It emptied my skull, so to speak, and other things came in, like the information I acquired from four wizards who came to visit me. I only did that because I read an old book that said the priests in Atlantis used to gaze at the moon from the tops of pyramids. And I understand why: when you do that, whatever’s in nature comes in. And what came in was unarguable knowledge, like gravity, wind, and the sun. This concept of unarguable logic is the origin of the whole Earthship idea.

The way you’re living is already radical to most people, and you were not afraid to let people hear that you had this vision — that’s another form of courage.

Well, I don’t go talk to a building inspector and say, “Hey, four wizards came to me and told me to build Earthships.” They’d just say, “Get out of here you hippie!” You’ve got to know when to hold ’em and when to fold ’em. But I don’t have a problem saying what happened, which is why I’m doing what I’m doing. I don’t have a choice anymore. A typical person has a career where they make money and a hobby that nurtures their soul. And then they have another thing they do to tune their body physically. And then most people have some kind of religion — they worship, meditate, and go to the synagogue or church. They have four different vectors to make themselves whole. What I’m doing is my hobby, the way I make money, my spirituality, and how I stay in shape all at once. It’s not a sacrifice. I’m not a martyr. I’m doing what makes me feel good physically, mentally, and spiritually, and it has a purpose.

I’m wondering about aesthetics and design because it’s a big part of what attracts people to your vision. Can you tell me how beauty functions in your work?

I partially paid my way through college by making paintings. I like art and sculpture — I almost became a full-time artist. Art for art’s sake is fun, but it didn’t have the purpose that, say, an Earthship has. I always played with art in my first buildings, but when I realized that I was working on a machine, I disposed of art and said, “If this machine works, it’s going to be beautiful.” No matter how much you decorate a boat, if it sinks to the bottom of the sea, it’s worthless. My first effort a few decades ago was to get this boat to float. At this point, they float, so now I decorate ’em. The one I just made is called Atlantis. It’s a piece of sculpture. Most people can’t afford that piece of sculpture, but I had fun doing it. The Refuge is very plain, a piece of functional science. But at one end of Atlantis there’s a white onion dome made out of refrigerator and washing-machine panels, and it’s an eight-room birdhouse. The birds out here in the desert don’t have many trees, so I integrated this sculpture into the building. These days I put a large percentage of my time into making structures that people can afford, so I minimize the art as much as possible and call the function of the building itself the art.

Michael E. Reynolds in an Earthship photographed by Luke Abby for PIN–UP 36.

The Castle Compound (1980). Image courtesy of Michael E. Reynolds.

Over the years, this substantial community has developed around you, and you’ve always been involved in teaching. How did you grow into your role as a kind of leader of a community?

It happened organically. I don’t really believe in leadership. Who leads the ocean? Who leads the bees? Who leads the horses? Who leads the trees? Nobody leads those creatures. It’s an inherent thing that they respond to. We have a whole dogma of leaders and leadership — religious or political — but we don’t need them. We need people willing to encounter the unarguable phenomena of the planet. I don’t want people to place me as their leader. If they place you up there, you’re only going to fall. I don’t want this to be about me as a leader. Christ was a leader, and it killed him.

By owning your life the way you describe it, you seem to have figured out an aspect of American dream that eludes most people — how to have radical independence without sacrificing security.

In a way, yes, but it’s not the American dream — it’s the Earth dream. I’m more radical than you could possibly imagine. I’m saying the government should provide Refuge housing to everybody when they turn 18. You can take the entire war budget and do that probably 15 times. Elon Musk, Bill Gates, any of those guys could take a few-billion dollars and house a whole country. And then you have all these people in a state of happiness. If you put the whole planet that way, it would be amazing what would be possible. I’ll tell you a good analogy that I tell myself. There are eight-billion people on this planet. I’m on a bus with 80 people, and they’re starving. I happen to have a bacon, lettuce, and tomato sandwich — I’ve got a sandwich that’s just the shit man! But I’m the only one with a sandwich. Can you imagine what would happen to me if I pulled out this BLT and started eating it? They would tear me and my sandwich apart. I feel like I’m in that position right now. I’m on a planet with eight-billion people, and yes, I’ve got my bacon, lettuce, and tomato sandwich, but I can’t enjoy it without everybody else around me having one too. So what I’m doing is simply trying to make it so I can enjoy my lunch and give everybody else out there their Earthship, their Refuge, their sandwich. It’s not about that “Do unto others” religious crap — it’s logic. The rest of the world will be after you if you’ve got more than them — you must make it so everyone has the same.

The Meditation Pyramid, completed in 1980, is one of Michael E. Reynolds’s early experiments when he started building in the Taos area.Inside, it has two levels and is designed for meditation or quiet rituals. The upper room features circular windows of colored glass bottles reminiscent of church stained glass. Photography by Luke Abby for PIN–UP.