Michael Anastassiades, IC 10 Anniversary collection for Flos, 2024; 24K gold-plated brass, glass. Photography by Daniel Riera. Image courtesy Michael Anastassiades Studio.

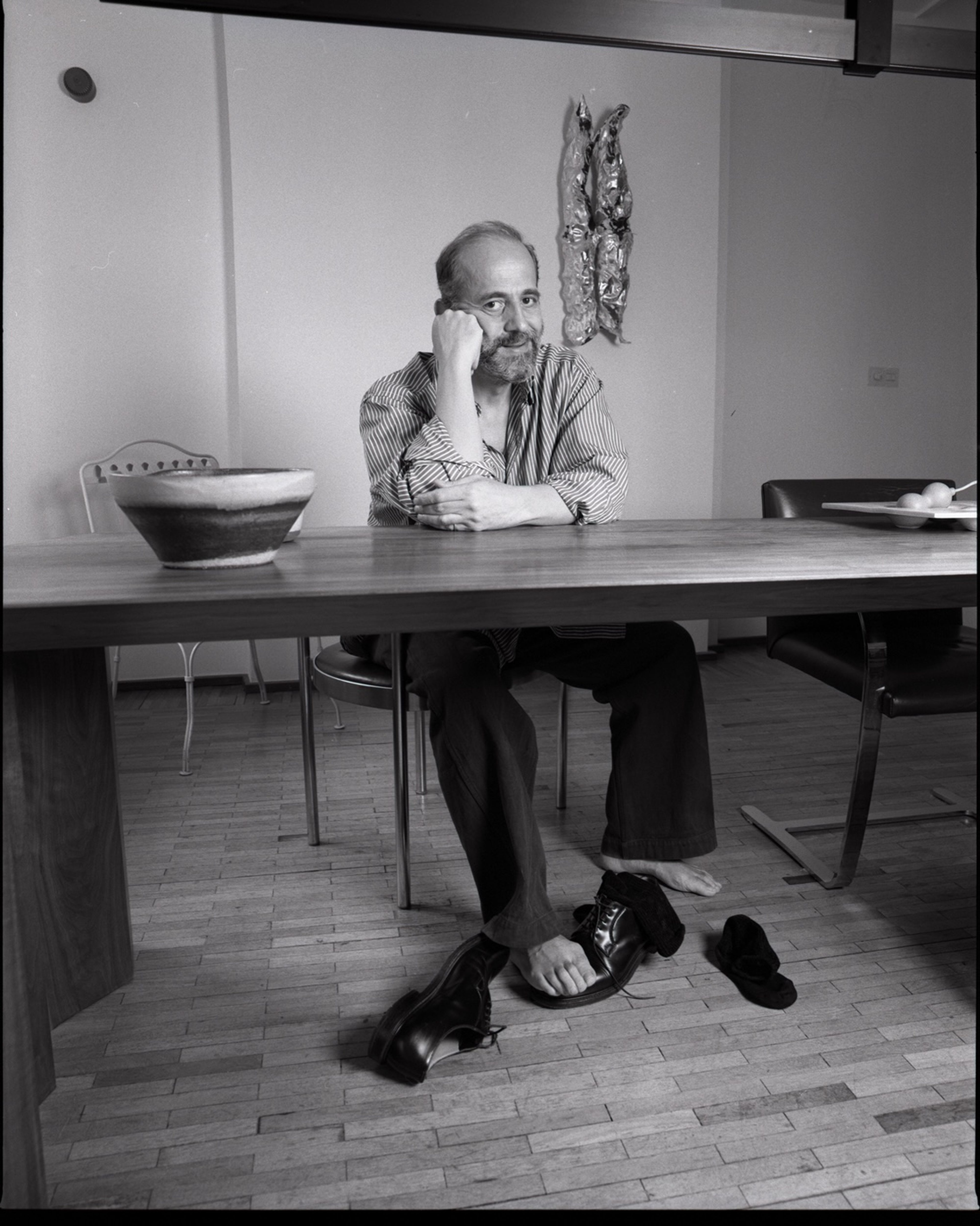

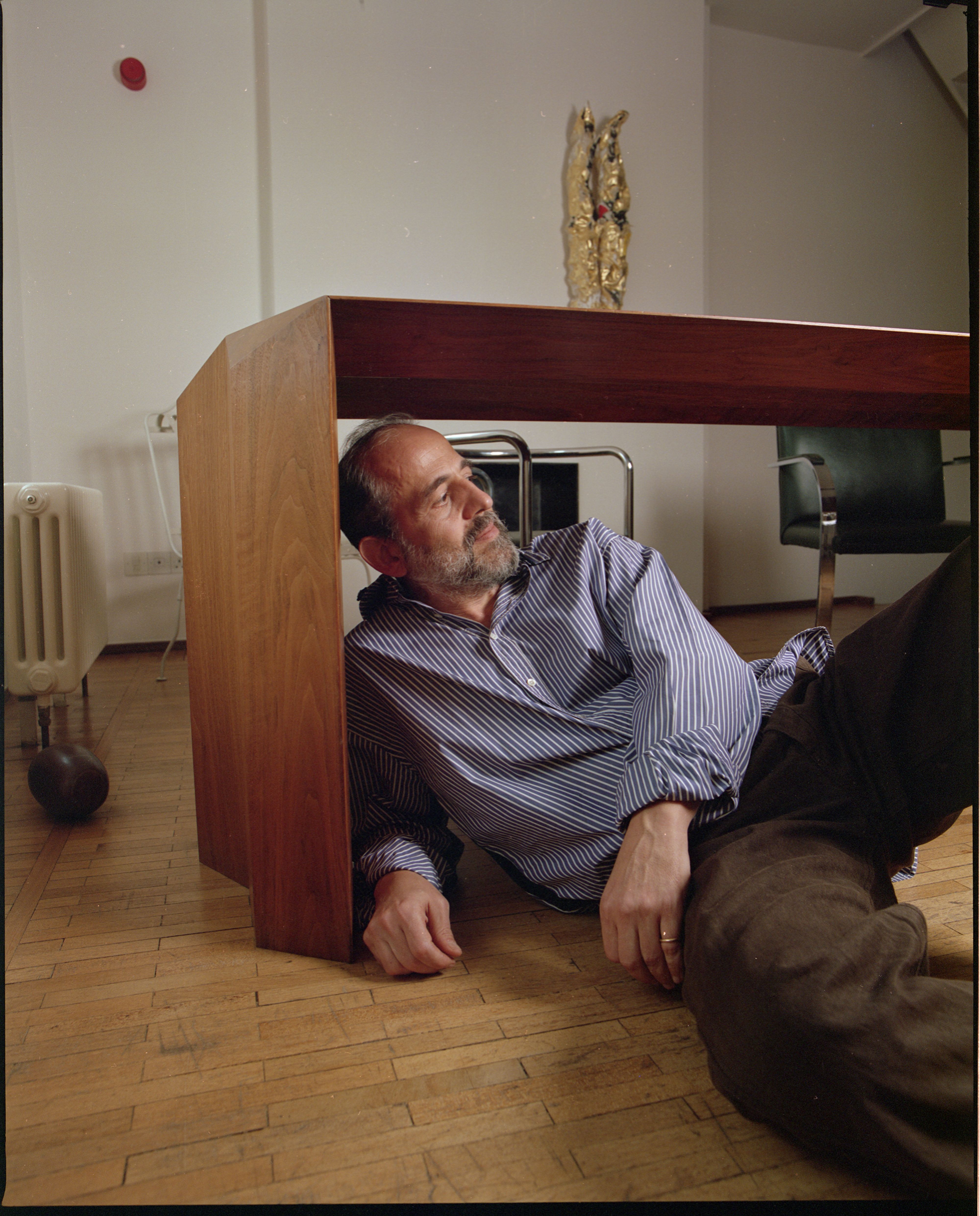

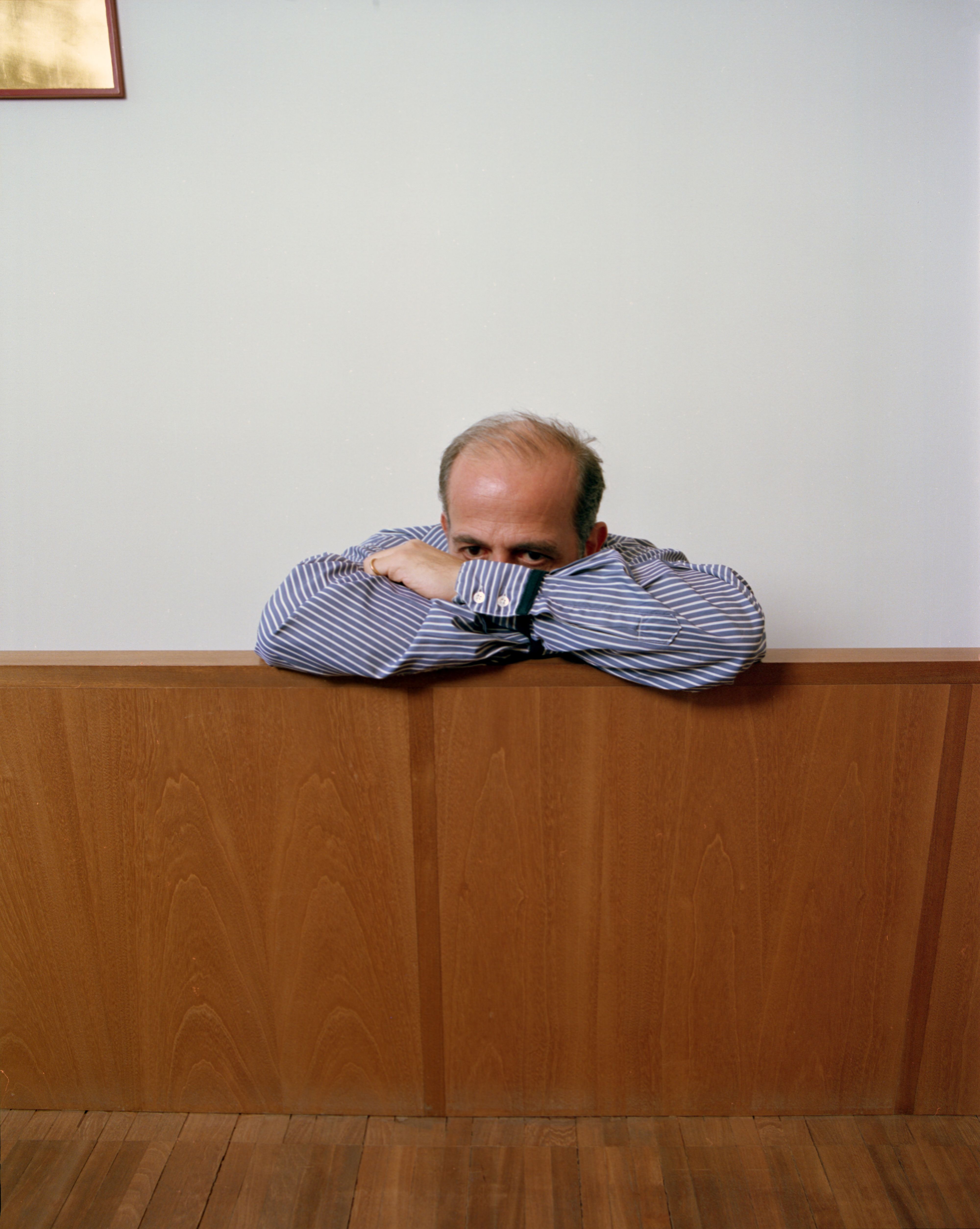

Michael Anastassiades photographed by Kuba Ryniewicz for PIN–UP 38.

In the saturated world of design, Michael Anastassiades’s work stands out for its understatement. Stripped of excess, his objects are both quiet and powerful, masterfully balancing proportion, scale, and materiality, delivered with a cool confidence of purpose. It’s no wonder he has become one of the industry’s most important assets, working with companies as diverse as Alessi, Cassina, Flos, Herman Miller, Molteni, and Tacchini. Meanwhile, his eponymous studio, primarily focused on lighting, caters to the bespoke market, and is represented by multiple galleries, including Nilufar in Milan and Friedman Benda in New York. Despite this roster of accomplishments, the 57-year-old is a relative newcomer to commercial design, having launched his first industrial products — a lighting collection for Flos — just over a decade ago. His current grandee status is quite a leap for the shy, Cyprus-raised Londoner who, after graduating from the Royal College of Art in the early 90s, felt lost in the world of design. A lucky break led him to a four-year stint designing fashion show sets for fellow Cypriot Hussein Chalayan, but he spent most of his post-grad years as a member of a highly conceptual collective dedicated to pushing design’s boundaries. The idiosyncratic objects they created — a talking teacup, a huggable nuclear mushroom cloud, a light that turns off when you speak — found institutional support but gained them no commercial clients. Anastassiades made most of his income teaching yoga, and only found a wider design audience in his early 40s, when his peers were already well into their careers. The big break came in 2013, when Flos began producing his IC Lights, a collection that defined the visual culture of its time (and has now become one of his most copied). Since then, Anastassiades has continued to create lights and furniture so precise and timeless they feel like historic classics you somehow missed. It’s tempting to call him a minimalist, though the term as used today, flattened into a surface-level aesthetic choice, doesn’t do him justice. Anastassiades reclaims the art of reduction, transforming it into something layered and philosophical — in his hands, simplicity has aura and intrigue. Thanks to his uncompromising vision, I wrongly assumed he was a rigorous aesthete, perhaps even intimidatingly serious. So imagine my relief when, over a dinner of salty pork belly and a few glasses of wine (from Alberto Alessi’s vineyard), I discovered Anastassiades to be not only charming but also very generous with his time and conversation. Reflecting on his story, he shared the obsessions, missteps, influences, and close relationships that brought him where he is today. One surprising, image-shifting, revelation was that his inner-circle includes one of the world’s most notorious maximalists, Sex and the City stylist Patricia Field.

Michael Anastassiades, IC 10 Anniversary collection for Flos, 2024; 24K gold-plated brass, glass. Photography by Daniel Riera. Image courtesy Michael Anastassiades Studio.

Michael Anastassiades, Clockwise table for Tacchini, 2024; marble. Photography by Andrea Ferrari. Image courtesy Michael Anastassiades Studio.

Michael Bullock: Sorry to start with what might feel like a tangent, but the fact that you’re close to Patricia Field comes as a surprise to me. How did you meet?

Michael Anastassiades: We met around 1996, through a mutual friend. I’ve always had an admiration for eccentricity. It’s almost like I wanted to have that level of eccentricity myself. Pat’s unique, a visionary. Her world fascinated me — she was operating on a different level. Her relationships and how she gave opportunities to so many people who were rejected by society is absolutely admirable. She never pretended to be something she wasn’t. Pat was always doing Pat, whether she was accepted or rejected. She was consistent in her path. I could relate to that. She was lucky at some point that circumstances brought her to the top. When Sex and the City came out, it changed everything.

I know some people involved in aesthetics to your degree draw strict boundaries to attempt to maintain visual consistency at all times.

Why would you do that? It has nothing to do with aesthetics. I don’t isolate myself and say, “This is not really my world.” I wouldn’t be able to have done what I’ve done in the way I did if I didn’t want to open up. It’s incredible to open your mind to everything and try to understand how other people do things differently. You can’t do that if you draw boundaries.

In social life, I agree. What about your practice? How is your studio set up?

The design studio is a creative firm that consists of me, an assistant designer, and a junior designer. The creative process is something I own, and I want to keep it that way. I want to go through every single decision and project that I’m responsible for. I’ve had this attitude right from the beginning. At most, there were two people plus me. I realized I never wanted to scale up. I came into design quite late in my life.

Michael Anastassiades photographed by Kuba Ryniewicz for PIN–UP 38.

Michael Anastassiades, Mobile Chandelier 13, 2017; patinated brass, glass. Photography by Michael Anastassiades Studio. Image courtesy Michael Anastassiades Studio.

Michael Anastassiades, Arrangements for Flos, 2017; powder-coated aluminium, silicone, polycarbonate. Photography by Santi Caleca. Image courtesy Michael Anastassiades Studio.

What did you do before?

I moved from Cyprus to London in 1988 to study civil engineering at Imperial College. I had always wanted to do something creative, but my parents wanted me to study something serious. They didn’t want to feel responsible for me for a long period of time — they wanted me to get a job. But I found engineering very strict, too controlling, too disciplined.

What did your parents do?

My dad never really studied. He used to do business things, a bit of real estate, whatever he could get his hands on. He was living in Africa for a while, where he met my mother. I was born in Athens, but I spent my first few years in Burundi. When I was five, we moved to Cyprus.

I read that you were always collecting stone when you were a kid.

Yes. I was fascinated with them because it was something that was there and available that I could collect, even in Cyprus. I was looking for the perfect shape. I had a fascination with the sphere, made naturally.

So, right from the beginning, there was always an obsession with form?

Looking back, I can see the connections. But as it’s happening, it’s not clear. I always say that I ended up doing what I needed to do through a process of elimination after first doing what I didn’t like.

Did you pursue any other creative activities in your early years?

I drew. In my immediate environment. I had nobody to relate to. But my dad had an architect friend, Neoptolemos Michaēlidēs. My dad eventually commissioned him to design a country home. He and his wife Maria, who was a painter, were both collectors. Neoptolemos had studied in the 1940s with Gio Ponti in Milan, but this was interrupted by the war. He managed to become an incredible Modernist architect, combining the designs of local historical houses with his knowledge.

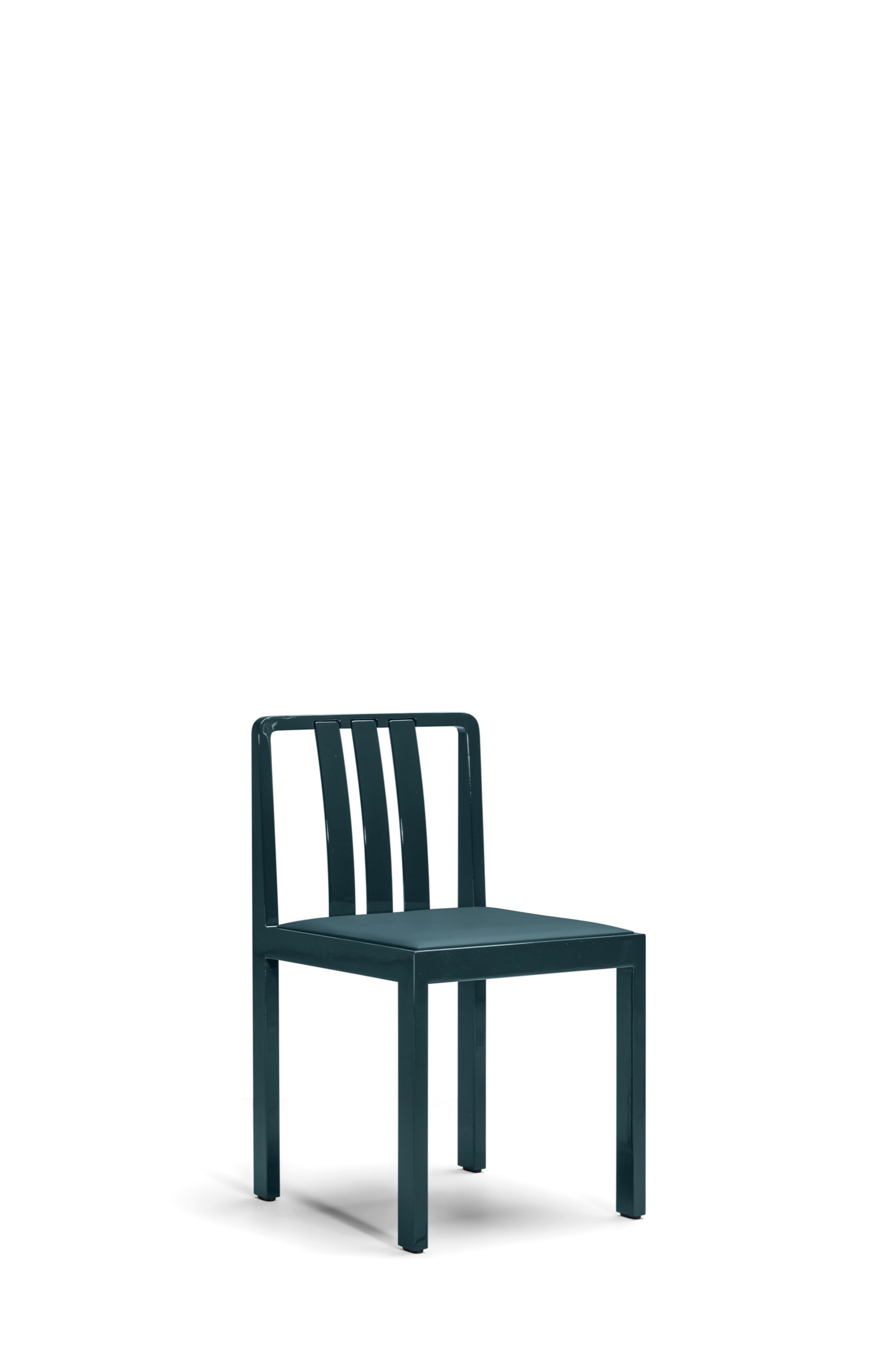

Michael Anastassiades, 1 2 3 chair for Molteni&C, 2024; painted and lacquered beech. Photography by Max Zambelli. Image courtesy Michael Anastassiades Studio.

Michael Anastassiades, XYZ for Brioni and Vogue House, 2019. Photography by Alexandros Pissourios. Image courtesy Michael Anastassiades Studio.

Michael Anastassiades, Huggable Atomic Mushroom, 2005; knitted mohair, foam. Photography by Francis Ware. Image courtesy Michael Anastassiades Studio.

Michael Anastassiades, Social and Anti-Social Light, 2001; bent plywood.

Photography by Michael Anastassiades Studio. Image courtesy Michael Anastassiades Studio.

Who else inspired you early in your career?

The Royal College of Art had a series of incredible talks featuring all these celebrity names: Jean Paul Gaultier, Philippe Starck, Ettore Sottsass, and also Alberto Alessi. In the late 80s and early 90s, Alessi was an icon. I remember him talking about failure, about being a young man joining the family company and working on all these failed projects, including one with Salvador Dalí. They were all quite conceptual, almost abstract, and they all initially flopped. I found it fascinating to hear someone so accomplished talk about failure. And of course I also remember being obsessed with the pictures of him with Salvador Dalí and his girlfriend, or muse, Amanda Lear.

You graduated from the Royal College in 1993. What happened after?

I knew I wanted to stay in London, but I didn’t know what to do. I liked design — I had at least established that — but I was unemployable. [Laughs.] I had no qualifications whatsoever. I had a very difficult portfolio when it came to getting a commercial job. My graduation project was a cup that recorded messages. Not for drinking, but one that you could talk to, and then put face down on the table, and then when someone you lived with found the cup, they could simply pick it up and it would play the message. I liked the work I was developing, and I always felt like a bit of a magician when I showed it.

It sounds like it was on the edge of conceptual art?

I didn’t want to call it art. For me, it was always about design. My frustration was that so many experimental things had happened in design in the 1960s, but by the time I graduated, the discipline felt dead. Nobody was questioning anything. I was reading all these books by Andrea Branzi and Superstudio, investigating the role of objects, and products, being really philosophical. And in the 90s there was nothing like that. Even later, when things like Droog Design started appearing, I found it interesting but not poetic enough. I felt like a misfit in every sense.

Michael Anastassiades, Message Cup, 1995; laminated birch ply, styrene, electronics. Photography by Michael Anastassiades Studio. Image courtesy Michael Anastassiades Studio.

Michael Anastassiades, Message Cup, 1995; laminated birch ply, styrene, electronics. Photography by Michael Anastassiades Studio. Image courtesy Michael Anastassiades Studio.

Michael Anastassiades photographed by Kuba Ryniewicz for PIN–UP 38.

How did you support yourself during that time of exploration?

A couple of years after I graduated, I discovered Ashtanga yoga through a friend who was a dancer. It wasn’t popular back then, but I got completely hooked. I spent whatever money I made on yoga classes, workshops, weekend retreats, and then more and more and more yoga. Eventually, somebody suggested I teach, and so my design studio used to double as a yoga studio. It was interesting having that dual identity. When people in the design world asked me what I did, I would say I was a yoga teacher. I felt it was more of an honest answer because that’s how I made my money. I wanted to keep my design away from all the contaminants that come with the career aspect of it.

What were you protecting?

I was protecting myself. I thought that it was better to make money from something completely different. I still had my studio, I was developing ideas, I was making work, but it was purely conceptual, like the teacup project.

You also designed a lamp you called the Antisocial Light.

Yes. It was a lamp that worked only when there was absolute silence. If you talked, the light would dim down and eventually switch off. There was another lamp called the Social Light, where you had to talk to it to maintain its glow. I was also doing a lot of experimental work with Anthony Dunne, who had been a visiting professor at the Royal College, and his wife Fiona Raby, an architect. We were all frustrated by the design world, so we decided to do a project together — Weeds, Aliens, and Other Stories. It was a book of ideas inspired by English gardening. We made about seven objects without any agenda. A simple body of work, but at the same time deeply intellectual.

And this eventually became an exhibition?

A few years later we got the opportunity to make it into an exhibition through the British Council Window Gallery in Prague. It was a big success. After that, everybody started inviting us to shows. We had a show at the ICA in London, and the Victoria & Albert Museum eventually acquired the project. There was a bench that you shared with flowers — it had a planter with holes below the seat so the flowers could grow through. There were also plant labels, like those you use when germinating seeds. Ours were electronic, and they read poems and recipes to the plants to help them grow. Another piece was called Rustling Branch: it consisted of a box with a hole in it and a motor attached underneath, the idea being that you clip a branch from a tree and put it through the hole, and then the motor, which was programmed to vibrate randomly, made the leaves rustle. We went on to make two other collections, Do You Want to Replace the Existing Normal? and Design for Fragile Personalities in Anxious Times.

How did you try to comfort fragile personalities?

It was a series of therapy products that helped you overcome your fears and phobias. One was called Huggable Atomic Mushroom. It was modeled after the mushroom cloud produced by a famous nuclear test in the Nevada desert called Priscilla. We made it into a cuddly toy. Our idea was that, if you’re scared of nuclear war, you just hug this mushroom so that it helps you become familiar with the idea.

Michael Anastassiades, The Philosophical Egg, 2019; Murano glass. Photography by Michael Anastassiades Studio. Image courtesy Michael Anastassiades Studio.

What prompted the shift toward the Michael Anastassiades we know today?

I started questioning my role as an industrial designer, asking myself whether I wanted to stay outside of it all and be critical or if I wanted to participate. Eventually, I had to decide how to engage with the industry, which meant finding meaning through a different type of object, whether a lamp or a chair. This coincided with my buying a house in London and deciding what I wanted to live with. I started looking for things I needed: “What kind of lights should I have? Does this feel right? No, it doesn’t.” My home became my laboratory.

What was the biggest risk you took when designing your home?

I always followed a feeling without really thinking about it too much. I wouldn’t have started my brand if I hadn’t been that way. Why would I want to start a lighting brand when I wasn’t even a proper designer? I didn’t know how to wire a lamp, and yet I wanted to create objects I could sell. I had to learn it.

Was it a period of anxiety?

I wasn’t in a rush. My yoga practice and my training taught me that there’s no one way of doing things and nobody should tell you how far you need to do something. Everybody works within their own limitations, insecurities, whatever you want to call it. Yes, I wanted to do all these things and I had many doors closing in my face. But I knew I had arrived at this new chapter through a very unusual route. Most people I went to college with had had a design career since graduation. I’d never worked for any successful design practices.

Could you identify a specific turning point?

In September 2006, I decided to host an open house during London Design Festival to show some pieces. On the last day of the show, Murray Moss [the American design entrepreneur] walked in. I had met him only once before, in 1998, when I did my first show at Colette, for which I made a table and a chair that were very conceptual. Murray came to see my Colette show and asked whether the pieces were for sale. I said, “No.” [Laughs.] As he was leaving, he said to me, “When you decide that any of this is for sale, here is my card.” I looked at the card, and I had no idea who he was. But, eight years later when he came to my house in London, I very much knew who he was. He said to me, “I want to buy this, I need it by this date. Let me know if you can do it.”

Michael Anastassiades photographed by Kuba Ryniewicz for PIN–UP 38.

What was the first product you made available?

The Tube Chandelier, which was originally developed for my own home long before I started my brand. But everything in my career changed when I decided to show at Euroluce in Milan in 2011. My assistant and I set up the booth — the smallest one I could afford — with furniture I borrowed from a friend who ran a Danish vintage shop in London and a rug I borrowed from Nilufar Gallery in Milan. The presentation received an incredible response. Patricia Urquiola had a little room next to me, and I had just met her and told her I was a big fan. Patricia was kind of a goddess to me because she was doing all these incredible things that I was aspiring to do, working in the industry at such a scale. I remember Ross Lovegrove and Konstantin Grcic were also there, and she turned around and said to them, “This guy is talented. We need to help him open the door to the industry.” I’ll never forget that. She introduced me to Piero Gandini, who was then the owner of Flos. She said to him: “If you don’t work with this guy, you’re stupid.” [Laughs.] She literally used those exact words. He was kind of thrown at first, but then he started looking at my work, and said, “I come to London sometimes. I’ll be there in October. Let’s have lunch.” And that was the beginning of another type of work for me. We started pretty much straight away with the String Lights, which launched in 2014.

Were they a success?

Let’s say they were a development. But six months before String Lights launched, Piero also saw the IC Lights in my office, which I had initially designed for my own brand. He wanted them for Flos, which was very unexpected. The IC collection has now become the biggest success for Flos, for myself, and everyone involved. I never thought that something so spontaneous could touch so many people. And it opened the doors for me to work with so many other brands. It still sometimes feels like a dream to me. Every so often I wonder if, had I started earlier, would I be working differently? But if I were to start again, I wouldn’t change a thing. That slow path led me to where I arrived today.

I’d like to end with harmony — I read it’s a word you don’t use with respect to design.

Harmony is not something I seek. For me, an object has to have a completely different reason for existing. It’s funny, because many people say, “Your work makes so much sense now that you tell me you’re a yoga teacher.” I look at them and think, “Actually, this is so remote from that, it’s not about the ultimate kind of serenity.” It could be there, and I’m not saying it isn’t, but that’s not the goal when I start. There are a lot of other things before that. Whatever the project — the Atomic Mushroom, the Message Cup, the Antisocial Light, the Social Light — it’s an evolution of ideas I’ve been carrying with me all these years. I never wanted to put words behind my work and justify anything I did, because I think the objects should say all these things themselves.

Michael Anastassiades, String Lights for Flos, 2013; aluminum, polycarbonate. Photography by Michael Anastassiades Studio. Image courtesy Michael Anastassiades Studio.