In Mexico you can have visible imperfections on a finished building and it’s fine, it can even be asset. You run with it rather than it being a flaw in need of correction.

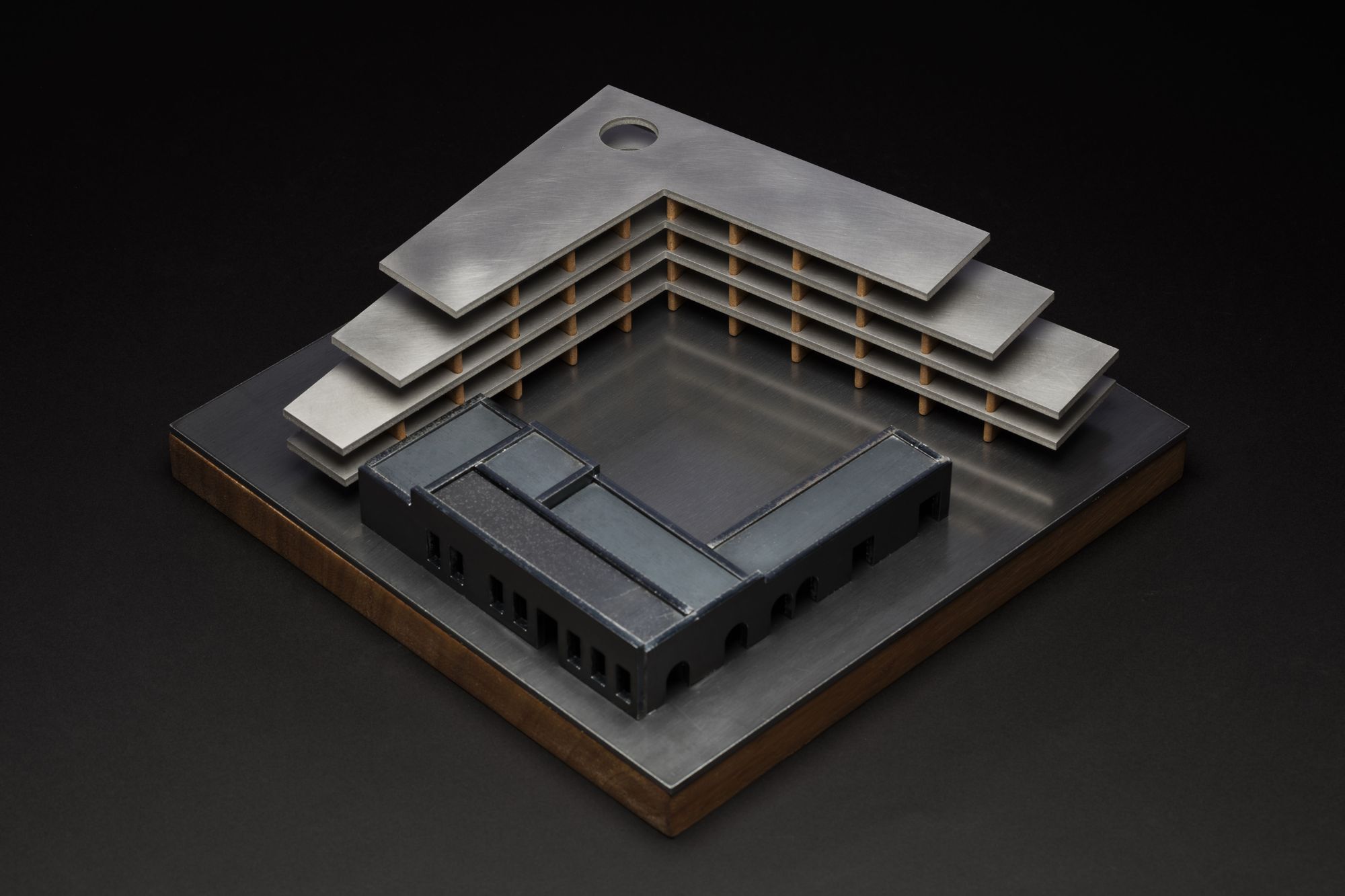

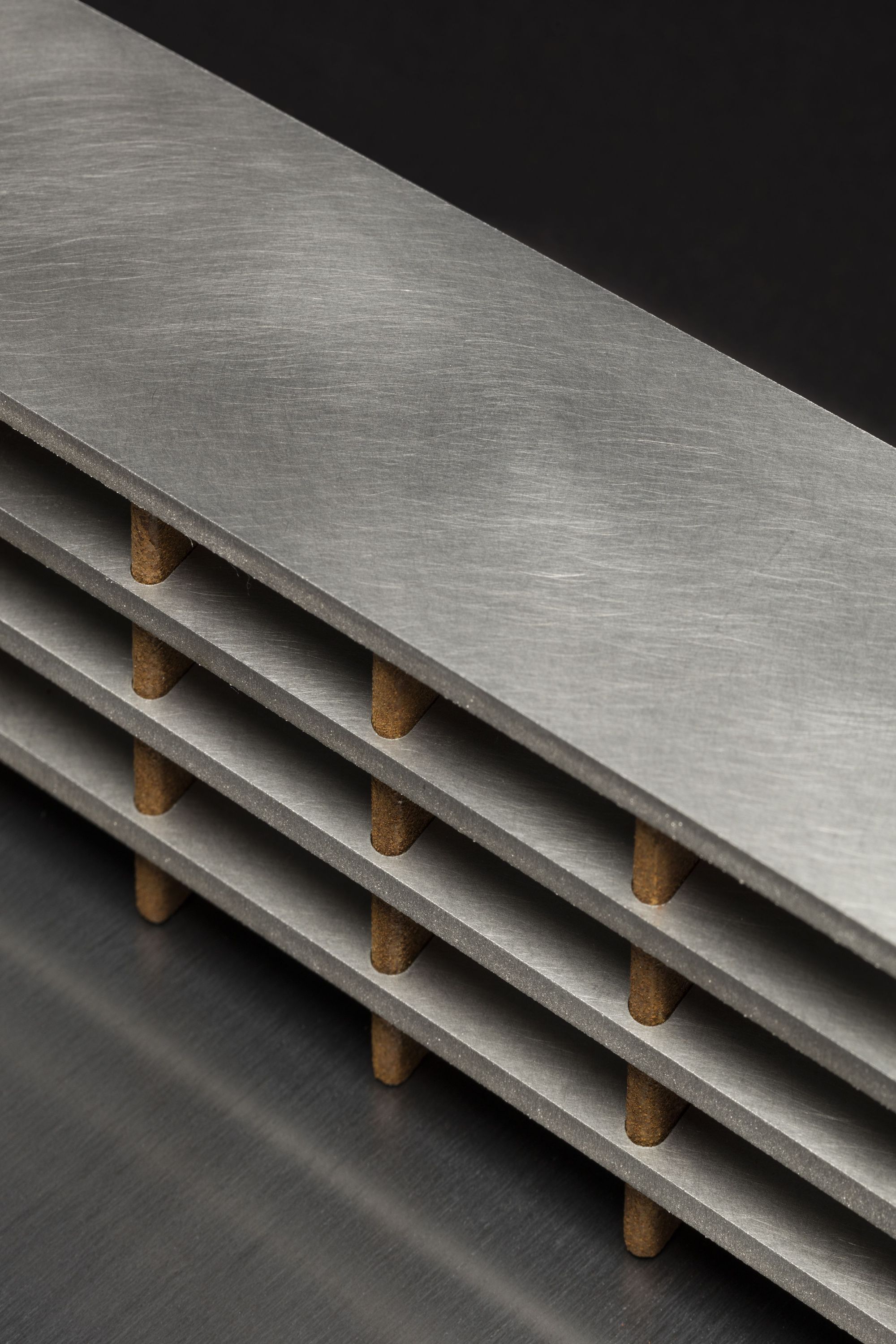

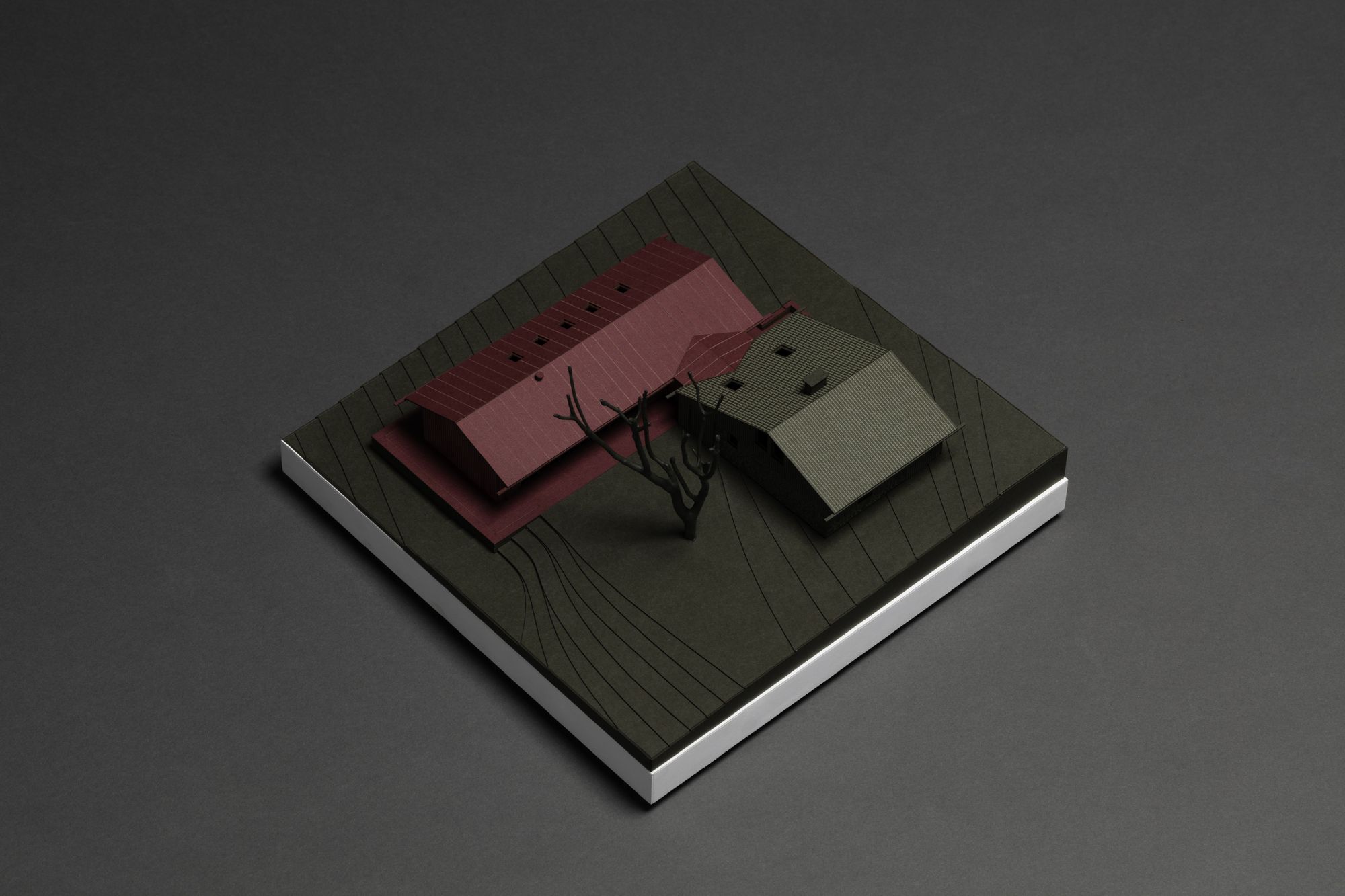

Completely. In Germany, you pour a concrete floor and it’s going to be so perfect it’s soulless. With Galería OMR, for example, we didn’t even have the option of doing a pristine white cube, and perhaps that was fortuitous. The starting point was a former classical-music record shop, Sala Margolín, essentially a Brutalist shoebox from the 1970s with a coffered concrete ceiling and four concrete columns. It was a gem in the rough that just needed to be cleaned up and polished. With our selective additions — a new floor and a steel curtain wall in the back — our ambition was to reference the original architecture and, in a way, tie back to that very specific Modernist moment, with a nod to Juan O’Gorman and the use of a Corbusian shade of red. In Mexico, I’ve discovered color as part of the architect’s repertoire, a tool to mask imperfections. We built OMR for 250–300 dollars per square meter, which is absurdly low. It’s less than social housing costs here, and you can see it — the finishes are a bit rough around the edges. You just make the best of what you have at hand.

Can you give me a quick synopsis of the past 50 years of Mexican architecture and where we stand today?

There was a Postmodern period, heavily influenced by Luis Barragán and epitomized by Ricardo Legorreta, after which came a bit of a hi-tech moment, with people like Enrique Norten, very much looking abroad, then a younger generation like Fernando Romero, Michel Rojkind and Tatiana Bilbao, who were still looking outside of Mexico for inspiration. The emphasis was on doing sleek, cutting-edge things, in some cases very digital. I feel the latest generation has a subtler approach. They’ve learned from the follies of the 90s and 2000s, reacting to an architecture that was trying to emulate something foreign and often didn’t correspond to Mexican realities — economic, technological, or cultural. Now you have architects doing humbler, smaller-scale projects using crafts, techniques, and materials that are actually available here, working with restricted budgets and perhaps with more of a social commitment.

Mexicans can be quite protectionist, culturally speaking. How have you become so fully integrated and fluent in the local culture?

MVW: Well, having a Mexican partner (art curator Ana Castella) certainly helps. But Mexican identity is hugely complex, confusing, and contradictory. Sometimes it’s difficult to read people, especially in Mexico City. The constant is that there is no constant. I also have some family ties to Mexico. More than 100 years ago my great-grandfather set up a huge Siemens hydroelectric power plant close to Puebla. And my mother lived here with her parents and siblings in the 1950s and 60s — she saw the flourishing of the so-called Mexican miracle, El Pedregal, all the great urbanism, etc. In a way my fascination with Mexican mid-century architecture comes from her.