I’m interested in understanding architecture and design through various forms of practice and not just the profession. Curatorial, editorial, pedagogical, research, activist, and professional practice are not independent activities; rather, their entanglements inform the same multifaceted thing: architecture. How do different forms of practice intertwine in your work?

AM: Our work unfolds in environments where we question the systems and paradigms that shape design. This requires us to speak critically, whether within academia or in the broader cultural and political sphere. Much of my work extends beyond the academy. Through publicly funded research collaborations with cities, industries, and research centers, we develop pilot projects that challenge building and urban planning regulations. These projects emerge from real conditions, where we negotiate with multiple actors including communities, ecosystems, and infrastructures, while navigating their frictions. In this way, each project is both a laboratory and a political act, testing how design can become a tool for systemic change. This is why I see multiple forms of practice as profoundly interconnected. Curatorship becomes a public arena for raising awareness. Writing generates new knowledge or reframes outdated narratives. Pedagogy is equally vital: my students’ questions push me to re-examine my assumptions and co-create new imaginaries. And, of course, design remains the medium through which these ideas take form and agency. When working with new ideas, there are often no precedents to fall back on. This compels us to move fluidly across practices, engaging diverse stakeholders and forms of knowledge. This approach acknowledges that architecture is never singular or fixed, but continuously plural, dynamic, and in flux.

LK: It’s a crucial question because the word “interdisciplinarity” is overused in architecture; it is often just a label. In my view, “interdisciplinary” work — bringing people from various disciplines together — differs significantly from “transdisciplinary” work. The latter creates a shared framework and a new paradigm in which disciplines co-produce a common approach. We both have diverse backgrounds in engineering, design, and the humanities, and our approach is grounded in an understanding of the practical limitations and possibilities, as well as how to achieve them. When we draw, everything originates from experiments, from data, and an understanding of how things work. Then, we switch from discussing the operation of a detail to discussing, for example, how Robin Wall Kimmerer, in Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge and the Teachings of Plants (New York: Milkweed Editions, 2015), uses botany as a science to explain phenomena of growth, evolution, and transference of biotic matter, embracing different kinds of indigenous identities. The passage from one field to the other is beautiful, but it also requires a lot of precision and depth in each field of inquiry. Transdisciplinarity requires us to shift between different modalities to experience, analyze, and design, traversing various layers of thought and production.

What is next for you both?

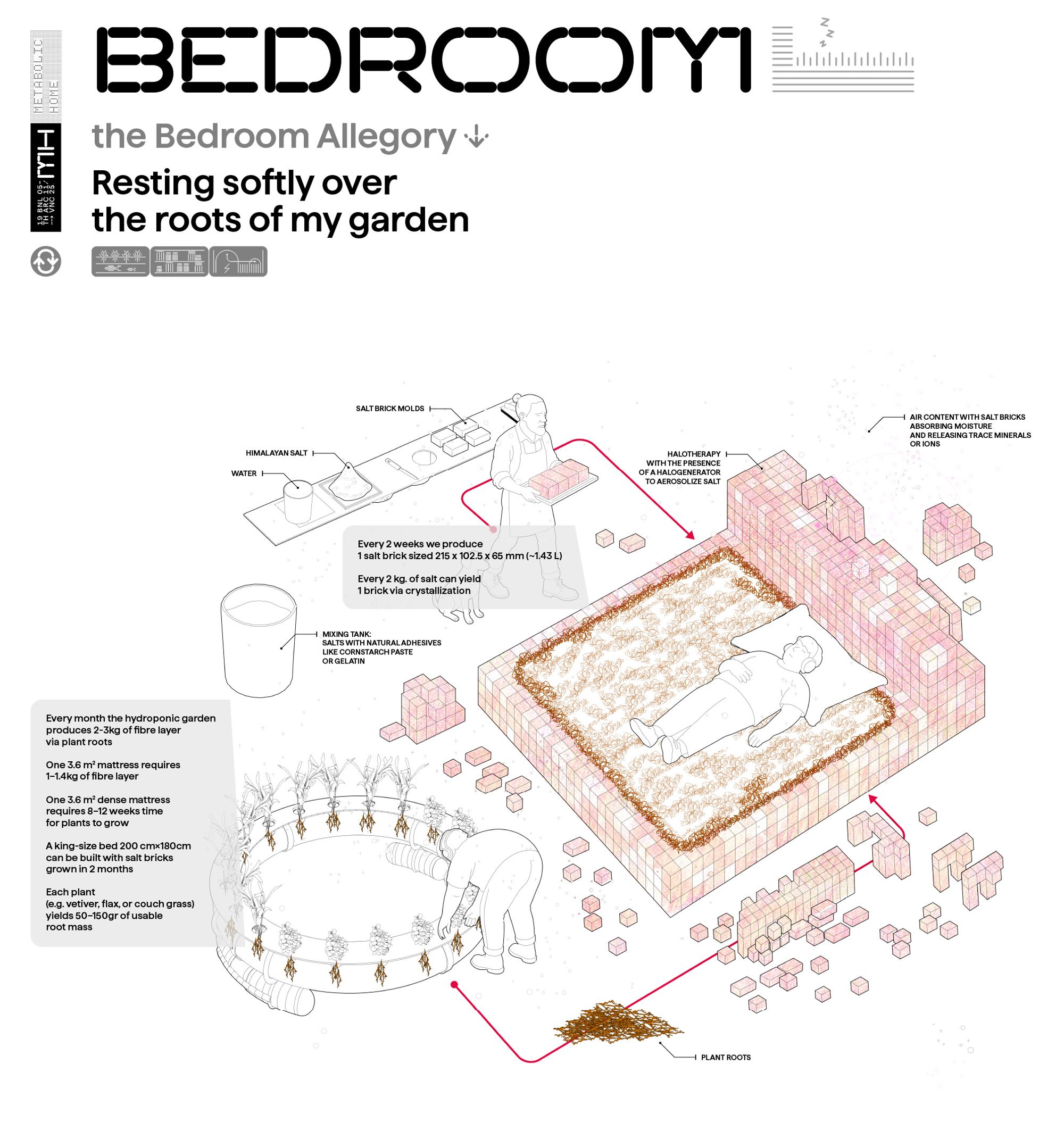

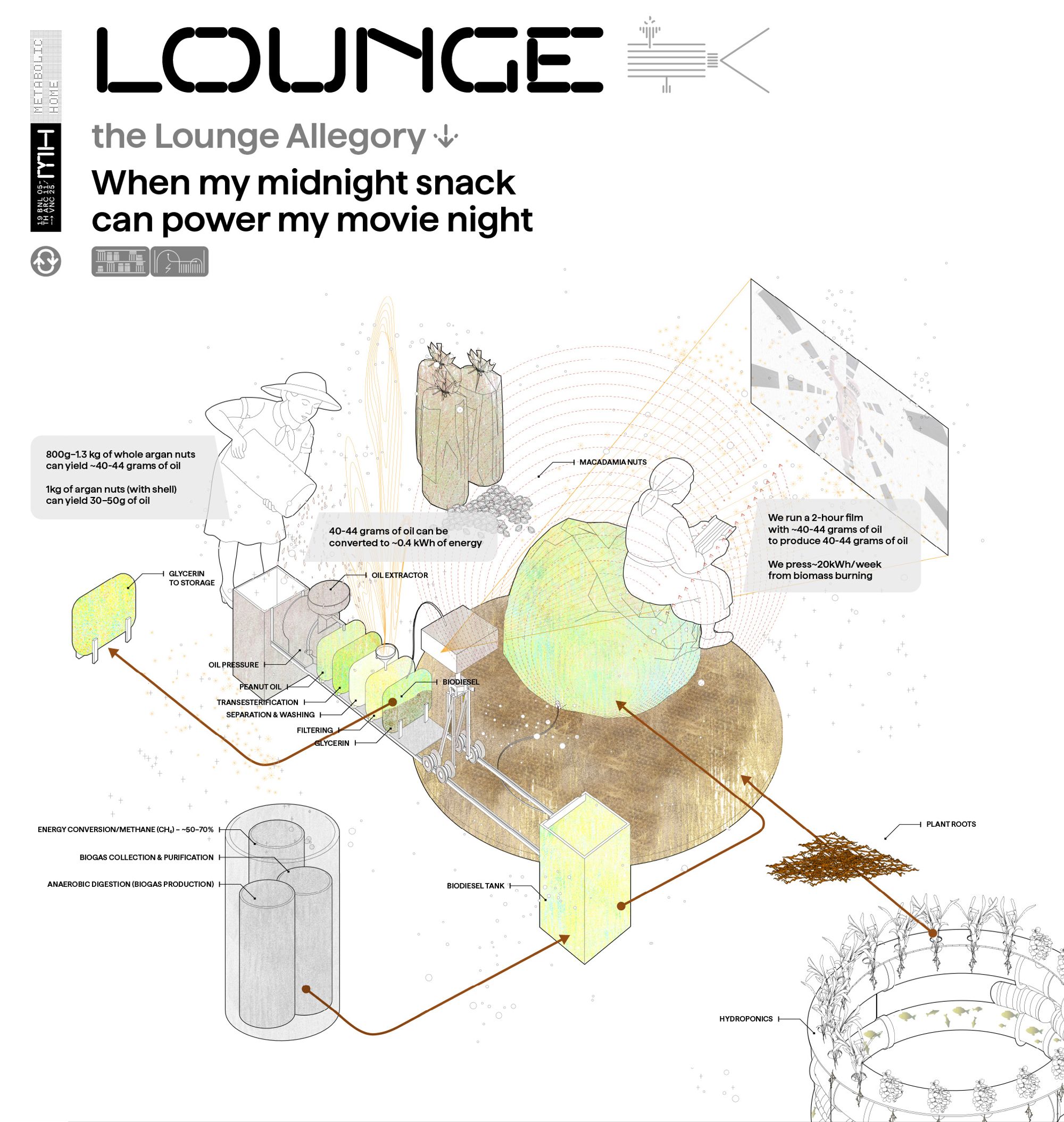

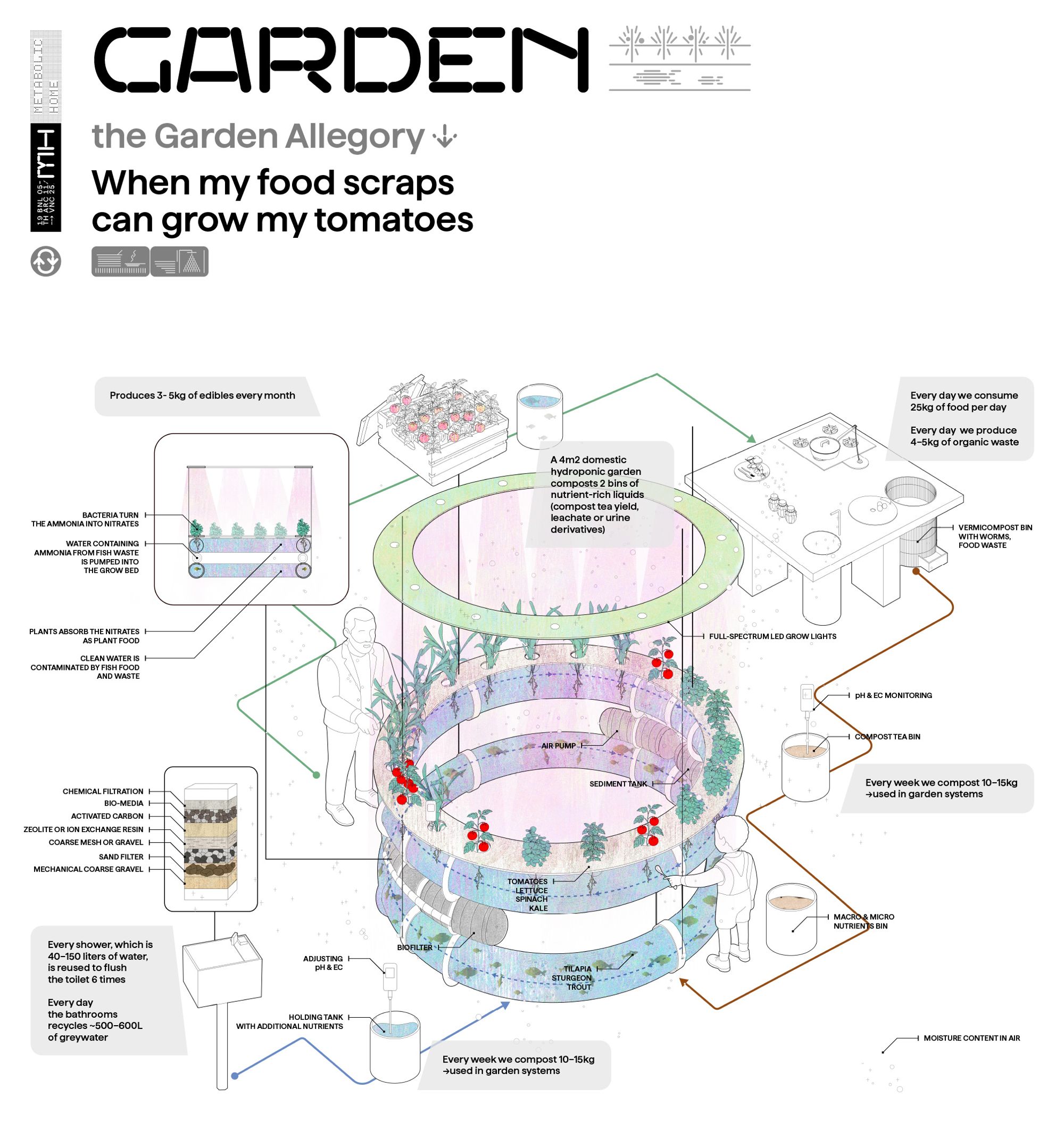

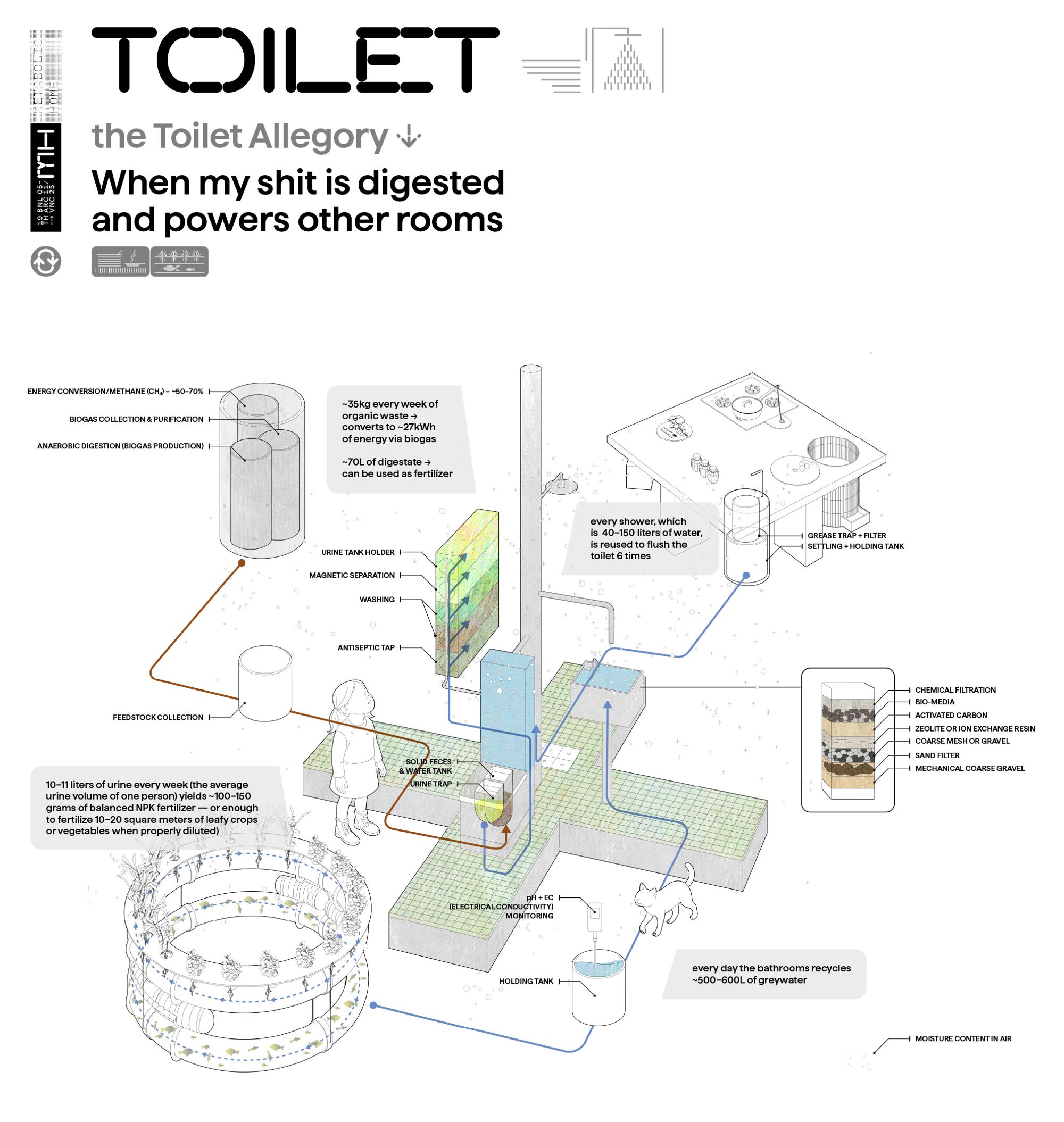

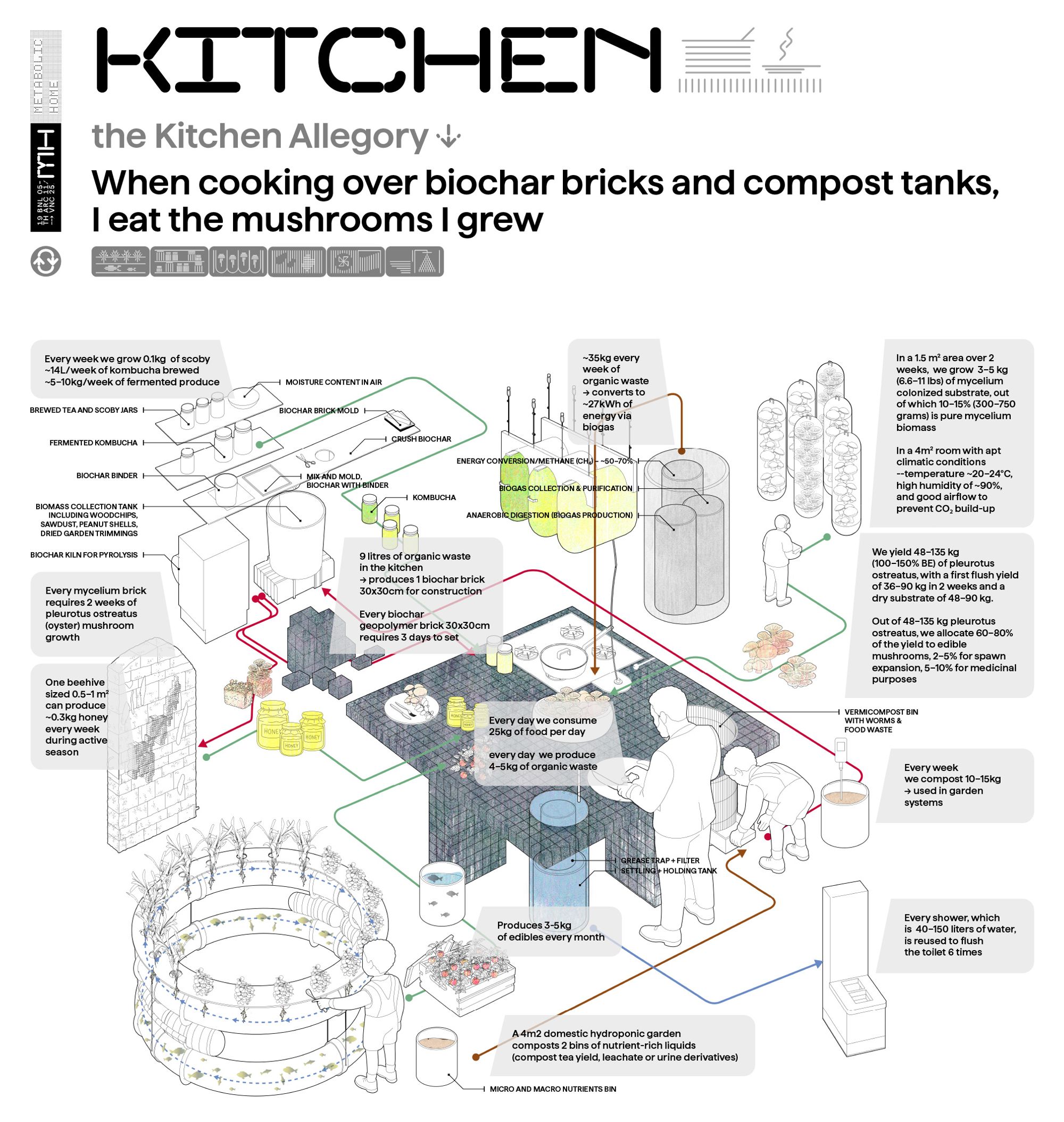

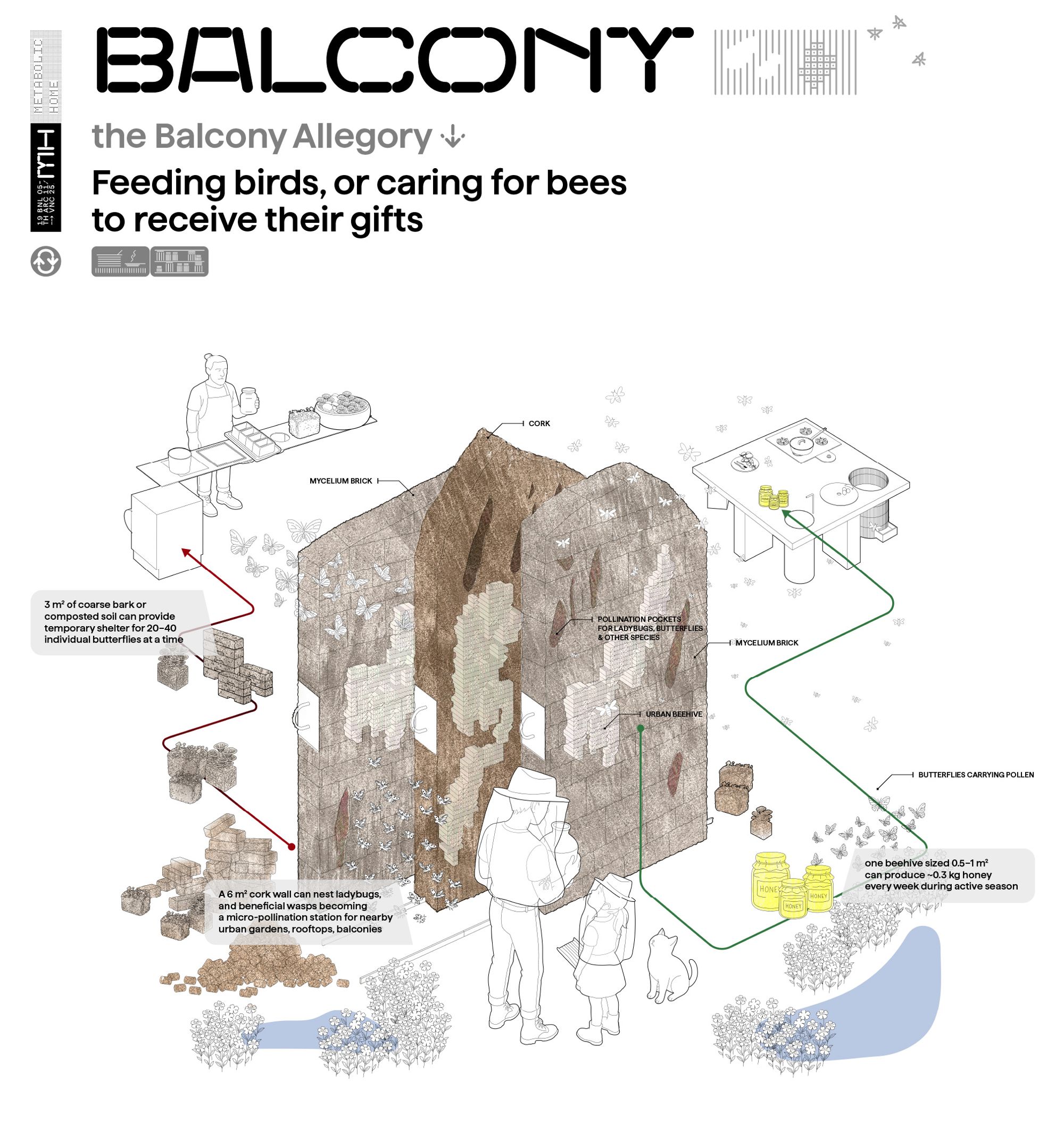

AM: Our next step with the Metabolic Home is to move beyond the 1:5 model and create a full-scale pilot to test how these systems can be built, inhabited, and maintained over time. This means scaling up waste-based materials into actual housing elements, integrating technologies from fields such as chemistry and biology into domesticity, and even experimenting with neighborhood-scale infrastructures. We have emphasized many times that the Metabolic Home model presented at the Venice Biennale is not utopian, conceptual, or purely speculative. Almost all of the technologies it showcased already exist. The challenge now lies in their practical integration into the domestic environment. We envision collaborating with multidisciplinary teams of scientists, designers, and industries to make this vision a reality; a radical model for inhabiting dense cities, and, perhaps, a blueprint for a new business model for the future of housing.