THE KITCHEN’S LEGACY RUSSELL ON THE AVANT-GARDE INSTITUTION’S DIGITAL FUTURE

by Emmanuel Olunkwa

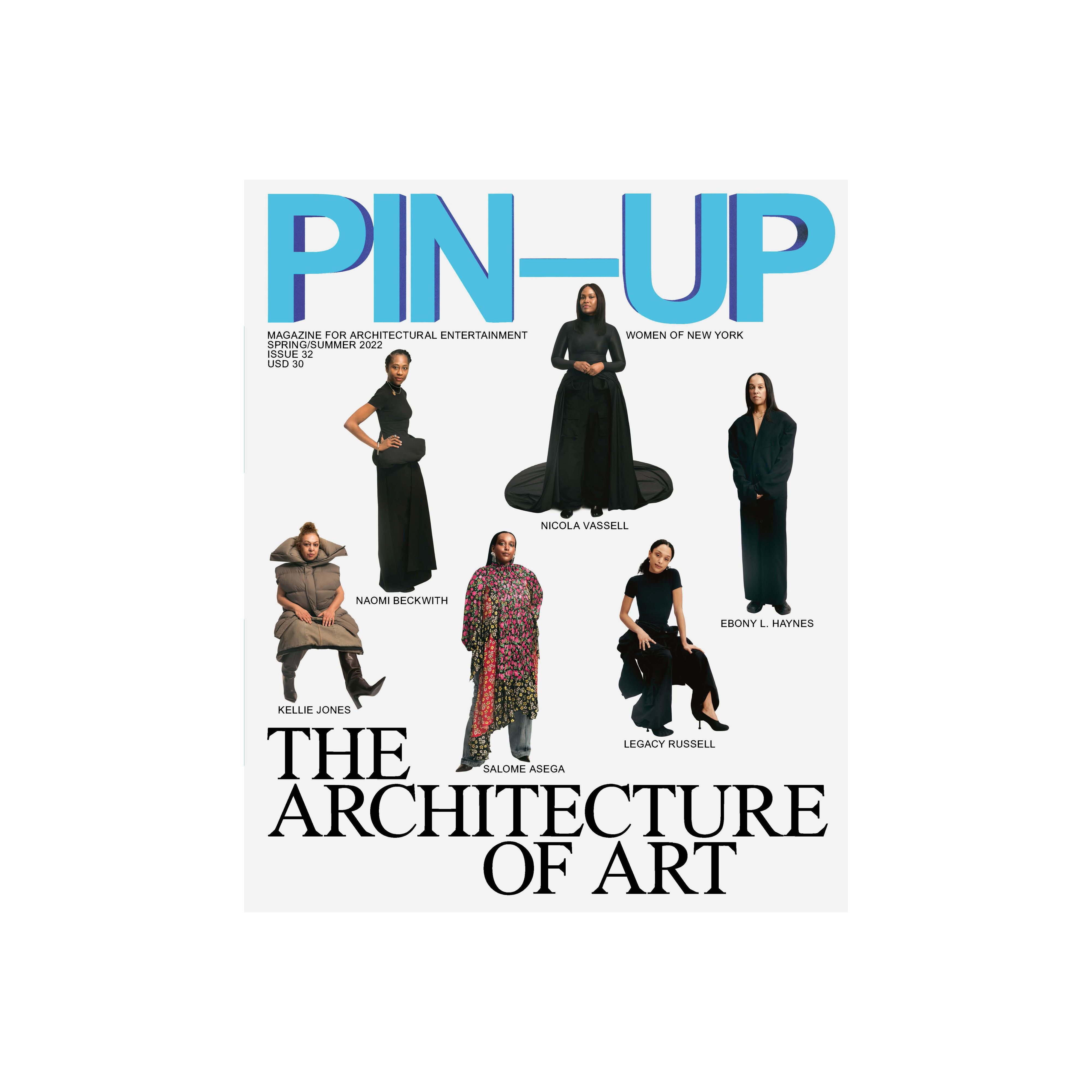

Legacy Russell photographed by Caroline Tompkins for PIN–UP.

If Thelma Golden calls you fearless, you know you’re doing something right. Legacy Russell is a writer and curator who embodies the term in its totality: her work consistently untangles the knotty binds between gender, performance and digital identities to push forward the vision of a queer, Black-imagined future. Golden has an intimate understanding of Russell’s keen curatorial perspective — the two collaborated together when Russell was associate curator of exhibitions at the Studio Museum, the role she held before her appointment as executive director and chief curator of experimental arts institution The Kitchen, which celebrated its 50th anniversary in 2021. Russell’s writing is as influential as her curatorial practice — in her acclaimed book of theory, Glitch Feminism: A Manifesto, published in 2020 by Verso Books, she draws out a whole world of possibility within digital slippages, proving that glitches and errors are actually ground zero for a radical form of non-conformity to white capitalist understandings of gender, race, and body. Her second book, BLACK MEME, which will map the emergence of Internet virality onto Black visual culture from 1900 to the present, is forthcoming from Verso.

Emmanuel Olunkwa: What’s your relationship to architecture?

Legacy Russell: Right now, the primary thing that is top of mind is The Kitchen’s forthcoming building project. It begins within the year and we’re thinking about what function the existing architecture has served historically and what it will serve in the future. We’re figuring out how the renovated building can allow for a more dynamic model of what our program can do and how that can serve artists.

What does the building need now that it didn’t have before?

The renovated building is going to allow for more durational programs rather than singular events that span specific days. This will allow for multiple touch points across multiple projects occurring simultaneously, with many floors inside acting as an extended footprint of the gallery and theater space. Those things will be realized and set into conversation with a maturated exhibition — our exhibition and performance program will be in dialogue with each other in a way that wasn’t possible before, largely because of the building we’ve been in since the 1980s.

How are you planning on situating The Kitchen in a digital context?

We’ve been thinking about The Kitchen without walls. We’ve been reflecting on the structure of brick and mortar and its not existing in opposition to the digital. We want to have a more integrated model that lends to a holistic digital footprint that’s in conversation with the physical space. It’s something I feel deeply committed to with my own ongoing work and research, which engages intersections of the digital and performance through and beyond the Internet. In the past, The Kitchen has had a deep commitment to the architecture of the building, which drove the programming. This feels inauthentic to our contemporary moment. People are experiencing art and institutions online before they are able to step through the doors in person. It’s an opportunity for and the responsibility of The Kitchen to reflect on how we can be generous with our audiences by thinking locally, nationally, and internationally about our digital footprint into the next 50 years. We want to be a place where people can experience our program no matter where they are, which means that they can engage with our archive. This also allows us to think about history and how it’s made and produced right here and now at an institution that is artist-centered and has historically been artist-driven. We’re also thinking about the parts of the program that can best be supported by the digital, specifically because The Kitchen has a really important route in terms of new media, with video work being its genesis point. It’s a full arc that’s really important because we began as an institution thinking about video and new media. We need to think about what it means to have an artist’s vision centered and celebrated, with digital being integrated into the performance pedagogy as well. Object-based exhibition-making can be performative, because objects labor as well, to answer your point about the architecture. Buildings are a part of what objects and performances should interrogate, so it’s essential to think about the site as a medium. That means every aspect of our work needs to be broadened and expanded to address how we can imagine that.

I don’t think there’s been a more opportune moment to rethink the spatial politics of time-based media. Given the new parameters of art, with non-fungible tokens, it’s important to think about how performance art and video have never fully been given dedicated space at most major institutions.

Exactly, which makes me think of The Kitchen’s mission that focuses on the framework of the avant-garde. It’s not possible to exist in this current chapter of the world and not acknowledge that most experimental work is actively engaging the history of digital practice and new media.

What we knew to be video art in the 80s is what we now consider the digital.

Digital presence and practices have created a distributed model of performance. In a way, performance is everywhere. It’s not siloed to a specific architecture, and that’s important in challenging our understanding of what can be considered experimental. It’s important to think about how we stage ourselves, because it’s not something that exists exclusively in the arts. Every day, to the point of Erving Goffman’s The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life, we have these relations in public and think about how we stage ourselves through and beyond different types of spaces. People are manifesting performance at a grand scale and they’re not even calling themselves artists, but they’re producing artful work, which as a possibility is incredible and ecstatic, but it can feel threatening to the canon of what an art practice is. This idea of art and art history is very much dependent on being a kind of rarified group producing rarified things in rarified language.

How did you start thinking about space and its producing context and meaning? Was it through language or art?

I would steer away from thinking in a binarized sense. I understand the opposition between language versus art, but that in itself feels heavy, and I don’t think that tension point is necessary. I often reflect on how poetry has been very instructive for me in terms of how I think about space and what it means to decolonize different types of architecture. One of the greatest tools of instruction is thinking about the methodology and pedagogy of curatorial practice in terms of how it needs to live in the future.

What do you mean by that?

I think it’s about the question of artful language and language that can exist within art to help us redefine how words and readership function. My hope for the future of what art can be is that we’re looking out across multiple lanes, where we are extending ourselves beyond the silos of art history, understanding that it can incorporate language as well to create a holistic, 360-degree view.

The WOMEN OF NEW YORK Special Cover of PIN–UP 32 is avaiable in a limited edition. Get your copy here.