Is the eponymous main character in Void angry?

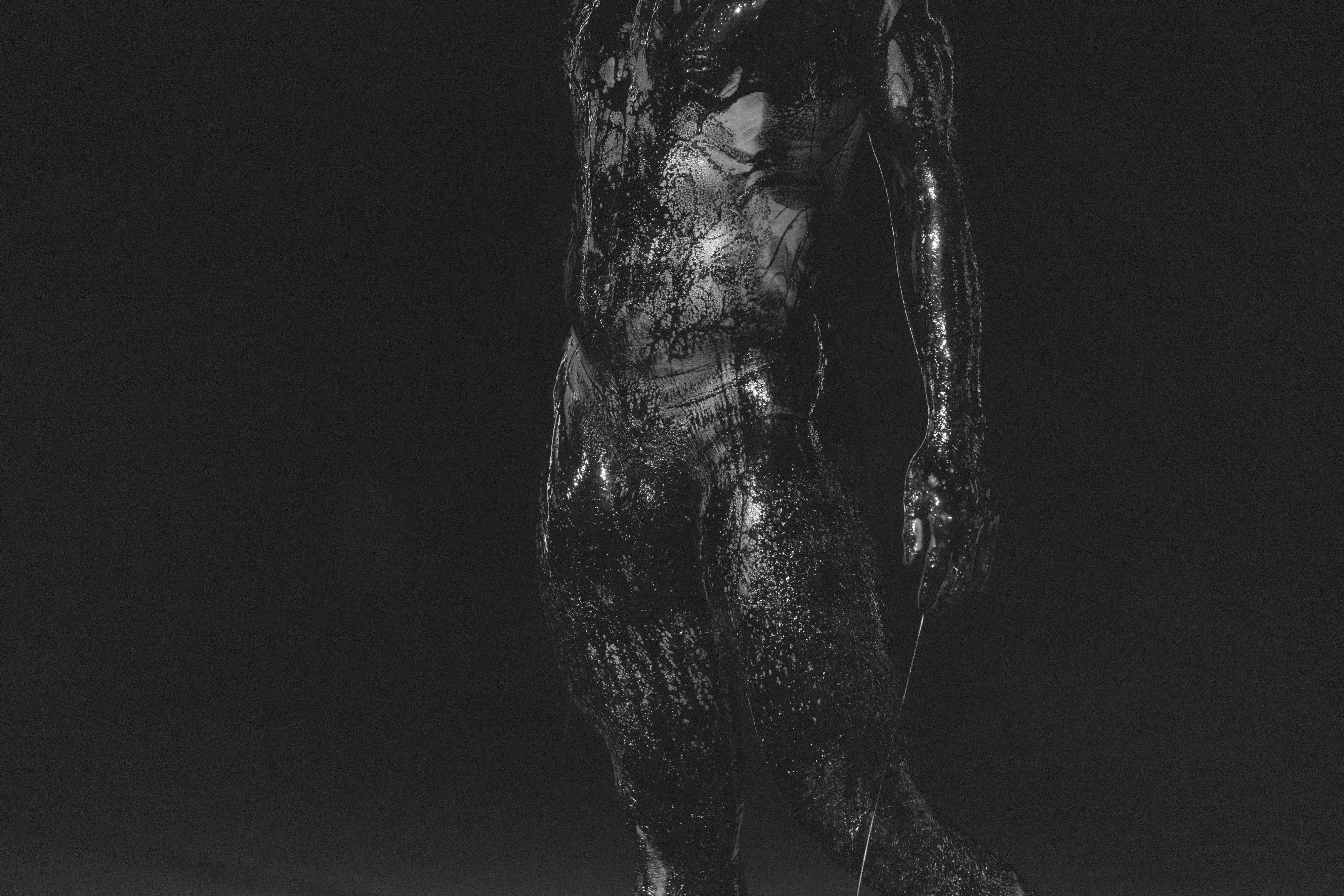

It’s in a lot of pain. Void is an alter ego I made based on all the traumas that I’ve accumulated. It is embodying global contemporary pain, coming out of dark things like sexual abuse, but also from the question: What would the god of the darkrooms or other taboo spaces of gay subcultures be? It surpasses time, and the black liquidity allows the body to disappear, in a way, and become an energetic force. All of us have our own little void inside; the question is how much you tap into it. Void gives this demon a space to dance — to express rather than repress.

You utter deranged-sounding things while you perform. What are you saying, or hissing, exactly?

I am mostly just cursing. The way I visualize it, spirits are talking to me and tapping me, and I respond to that.

How was performing Void at the Cárcamo de Dolores different than staging it in other spaces?

Void had been performed in Hong Kong, Belgium, Germany, Finland, and Singapore. The Berlin performance, at the Haus der Kulturen der Welt, was special because it was also outdoors and engaged with the architecture. Berliners know the [1950s] building we used as the “Giant Oyster,” but it also looks like a giant spaceship. So I thought, let’s play with that; we designed the stage to balance that specific environment. For the TONO performance, the venue was confirmed the day before I flew here, so it was all very last minute. The site is obviously amazing, not just because of its history and architecture, but because I’d never performed in what is sometimes called the Global South. As a brown maker, this was very important to me — a dream, so to speak. And of course you have the synchronicity of this massive architecture of a god in relation to Void, who is trying to become a God. My dance manifests all the emotions of the three deities that birthed Void, an accumulation of anger, love, pain, carnality, and sadness over millennia. How do you understand centuries of human history? How do you make a dance out of it? That’s why it has this tentative quality. Even a just-formed god can’t make sense out of the inequality, wars, and uncertainty of our world. It was uncanny to have a massive god lying down in a fountain right behind all this unfolding. I made an offering to Tlaloc before the show, affirming it’s his space and asking for permission to ask questions he might already have the answers to: Were you me? Are you my reincarnation? How does one become a god? Let’s not forget humanity and civilization created its gods. In the end, my goal is that when future archaeologists dig up the remnants of my work, the gods they find are trans queer bodies, and they’re Filipino, with Filipino standing for any community whose narratives have remained unheard.

Did you make any changes for the piece’s performance in Mexico City?

We added a part at the end, a recording of a text. In previous performances, Void dies as the music ends, closing the cycle. This time, we wanted to add something that invited the audience to engage, asking them why they came — was it for salvation, liberation, or confrontation?