A Thousand Layers of Stomach, A.A. Murakami, 2024. This textile work, rendered using generative code, was inspired by the patterns of the Asari clam shell and debuted at Art Blocks Weekend in Marfa. Courtesy Trame.

A portrait of Ismail Tazi, who founded Trame in 2020, a design studio that explores the intersection of traditional craft and technology. Courtesy Trame.

Ismail Tazi didn’t take the straight road to design. Raised in Fez, Morocco, and educated in Paris, Tazi spent years navigating the creative and finance world before deciding to build something of his own. In 2020, along with his uncle-turned-collaborator Adnane Tazi, he launched Trame: a gallery and studio dedicated to reimagining the relationship between craft, technology, and cultural memory. Early projects, curated by Valentina Ciuffi, paired contemporary designers with master artisans. Tales of Imperfect Repetition — a 2022 collection of digitally fabricated ceramic vessels by parametric architect Arthur Mamou-Mani — marked their “bridge” to new technologies and working with artists from the so-called “generative art” realm, who rarely see physical manifestations of their work in the design world. This collection sharpened Trame’s focus: heritage reimagined through generative processes and digital tools, which they’ve continued with each new project and exhibition. Trame straddles two design worlds at once, collaborating with both conventional architects and designers like Studio Swine and Aranda \ Lasch alongside generative artists and creators — Jeff Davis, IX Shells, Linda Dounia — who have amassed large online followings yet are still little known outside the generative art bubble. In the past year alone, Trame has unveiled five new collections and showcased them at notable events such as Art Blocks Marfa Weekend, the International Contemporary Furniture Fair in New York City, and Downtown Design Riyadh. These include, among other works, a series of algorithm-driven tapestries by A.A.Murakami, stained glass pieces by Jeff Davis, and a set of generative bistro chairs created in collaboration with Maison Louis Drucker and Aranda \ Lasch. These chairs are now available through the Enlace app, which allows designers and customers to algorithmically design their own personalized patterns. Talking to PIN–UP, Tazi reflects on the future of design, code-switching, and why the real avant-garde is happening somewhere between a medina in Morocco and a blockchain server.

Desert Threads, an alternative tapestry series by Trame, IX Shells, Linda Dounia, and Fingacode in Marfa, Texas in 2024. Courtesy Trame.

A Thousand Layers of Stomach, A.A. Murakami, 2024. This textile work, rendered using generative code, was inspired by the patterns of the Asari clam shell and debuted at Art Blocks Weekend in Marfa. Courtesy Trame.

The Art Blocks Engine weaving A Thousand Layers of Stomach by A.A. Murakami.

Felix Burrichter: Can you tell me about your background?

Ismail Tazi: I was born and raised in Fez, the historical capital of Morocco. It’s 12 centuries old, with the oldest continuing university in the world, the University of al-Qarawiyyin, which was built in the ninth century by a woman [Fatima al-Fihri, the daughter of a wealthy merchant], two centuries before the Western world’s first university was built. I grew up in a family of historians and scholars, and was surrounded by crafts. The embroidery of Fez is very well known, and my great-grandfather was in the silk business, and my great-grandmother embroidered silk. As long as I can remember, I would walk through the streets of the medina looking at crafts. Everyone would tell me how marvelous it was, yet I only saw the same patterns, designs, and colors we’ve been repeating for six centuries — no innovation. It wasn’t until I left to study in France at the Sorbonne that I embraced the Arab contemporary art scene thanks to the Institut du Monde Arabe (IMA). It’s one of the only institutions in the Western world that celebrates Arab culture and was my entry into the art world. Five years later, I moved to London, and it was there I realized how curious I was about the impact of technology on the creative industries, so I launched Trame.

Woven chair by Trame, Maison Louis Drucker, and Aranda \ Lasch. Each chair is a physical output of a digital token, redeemable at Maison Drucker. Courtesy Trame.

Can you speak a little bit to that name?

In French, Trame refers to the trame d’un textile which refers to the weft of a textile — the horizontal threads in a woven fabric that are interlaced with the vertical ones. So it’s about this interwoven quality and encounters between the threads. What I do is about encounters — encounters between people, between the contemporary and heritage, between the physical and the digital. Trame symbolizes that mindset.

What were Trame’s first few projects?

Our first project, A Voyages to Meknes, launched in 2020, a few weeks before the pandemic hit. We took designers Julie Richoz, Maria Jeglinska, and Maddalena Casadei to Morocco, where they created ceramics and textiles combining their contemporary approach with traditional Moroccan ways of making. It wasn’t digital — it was very straightforward — but it was innovative in terms of connecting contemporary designers with Moroccan craftsmanship. In 2021, we took another set of designers — Sophie Dries, Objects of Common Interest, and Giovanni De Francesco — to Calabria, Italy, where they collaborated with the local artisans to create handcrafted seminara masks [traditional clay masks from Calabria known for their grotesque faces and protective symbolism]. The third collection, Tales of Imperfect Repetition, was inspired by Alhambra in Granada. We worked with Amandine David, Wonmin Park, and Arthur Mamou-Mani, who each 3D-printed then hand-glazed a series of ceramics. That was the first project where we used new technologies for fabrication, and it showed at the Institut du Monde Arabe in 2022, which was extremely fulfilling. The fourth, Navette, was a collection of generative tapestries produced by Tokyo-based French artist Alexis André. He traveled from Tokyo to Aubuisson, a six-century old region in central France that has historically set the gold standard for tapestry, to produce a series of unique tapestries on a digital Jacquard loom. It was both digital fabrication and code-based art.

Production of the Enlace chair by Trame, Maison Drucker, and Aranda \ Lasch. Courtesy Trame.

Production of the Enlace chair by Trame, Maison Drucker, and Aranda \ Lasch. Courtesy Trame.

Enlace chairs by Trame, Maison Drucker, and Aranda \ Lasch. Courtesy Trame.

What’s interesting to me is that the starting principle was not necessarily generative design, but the desire to collect different features and craftsmanship.

What I have always liked about craftsmanship, with Moroccan Tamegroute ceramic, for example, is that even if you make the same type of ceramic, each one will still be different. With generative design, it’s about building a systematic approach to creating this same type of difference. After the tapestry collection, we worked on the generative bistro chair with Maison Louis Drucker and Aranda \ Lasch. We showed three of those chairs and two from their regular collection at Art Blocks last year to show that we can apply generative patterns to the entire Drucker catalog. So, effectively, a hotel somewhere could develop their own pattern and have the digital provenance to it through an NFT, making that pattern theirs for a period of time.

How do you decide who you want to work with?

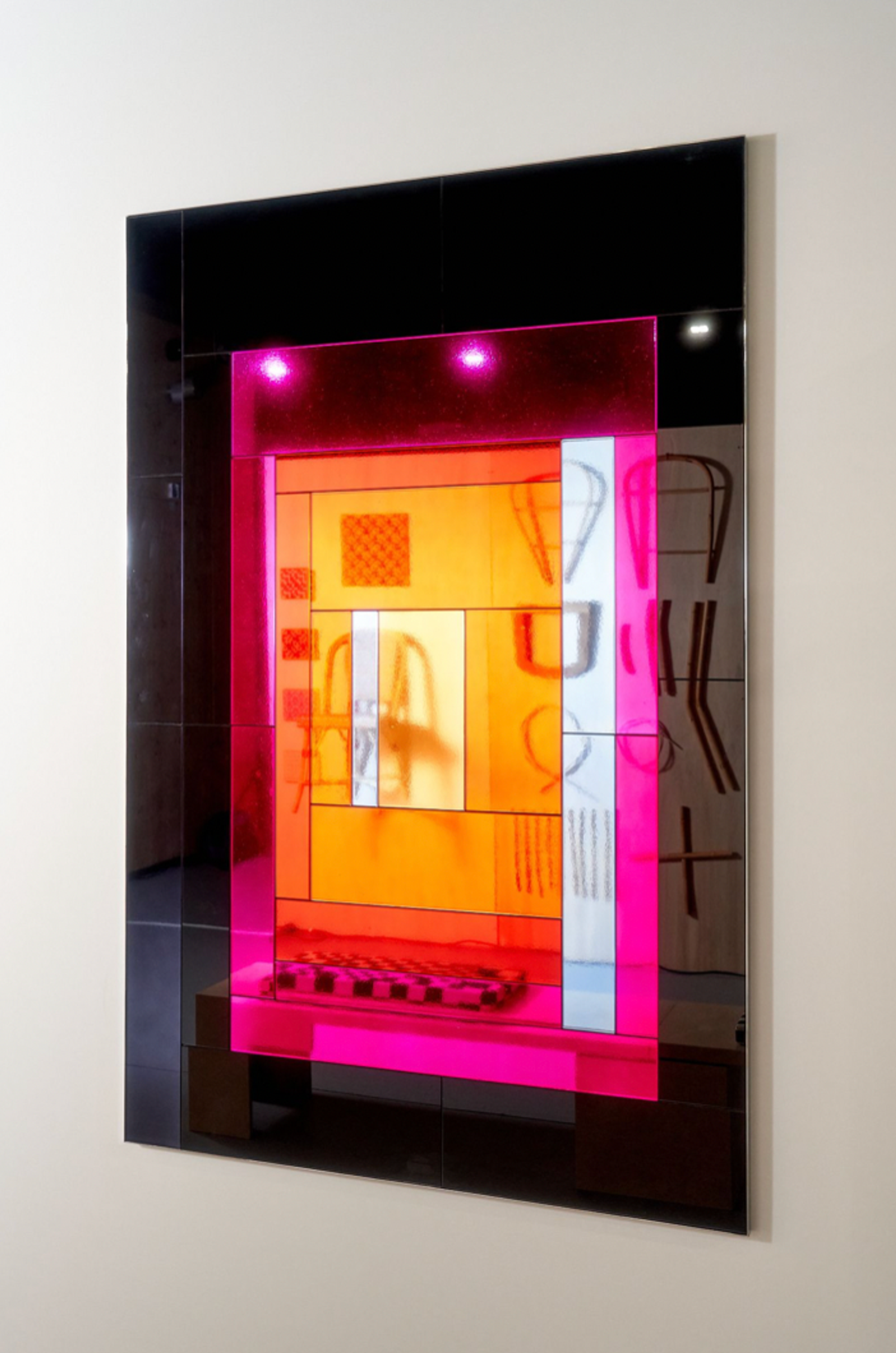

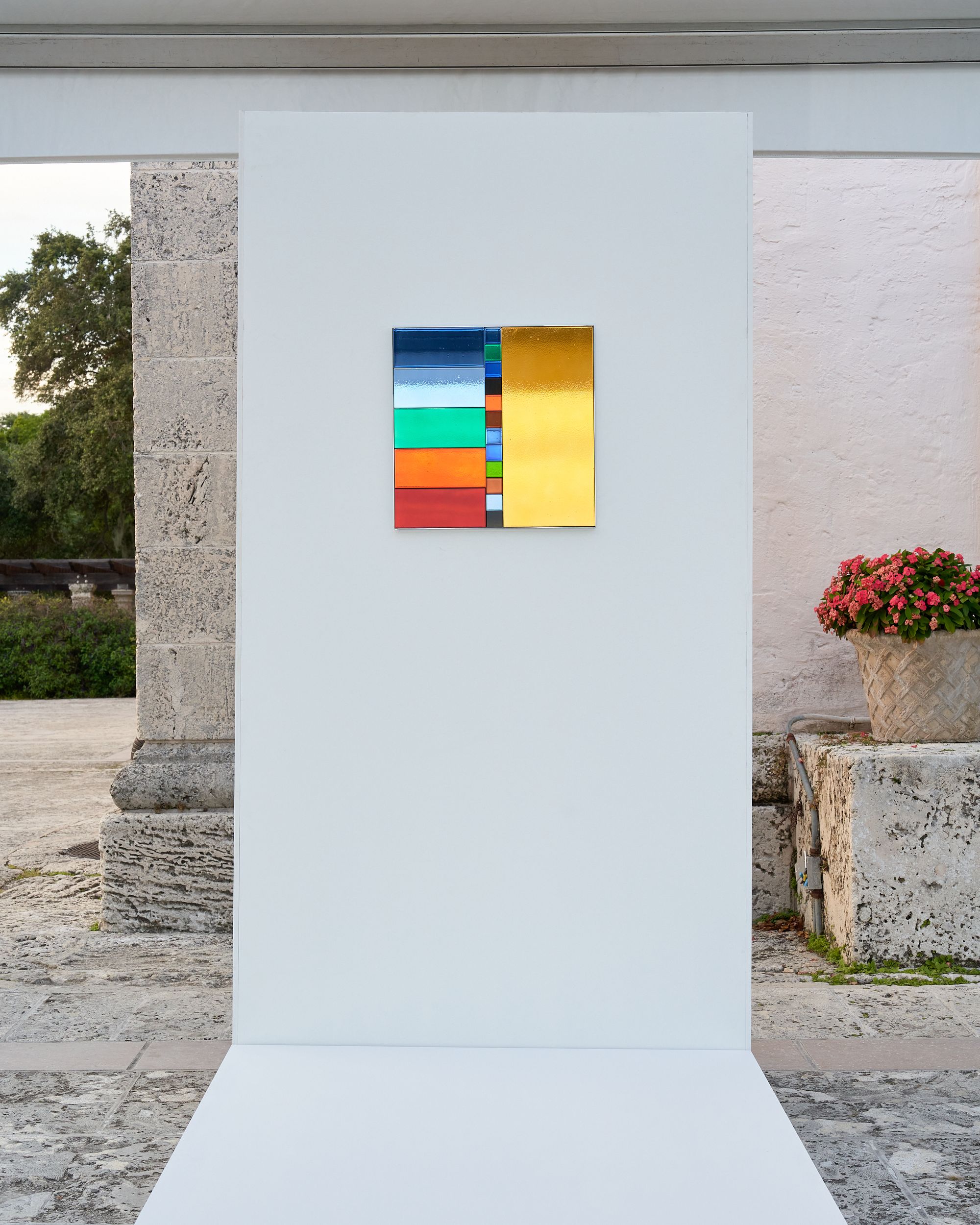

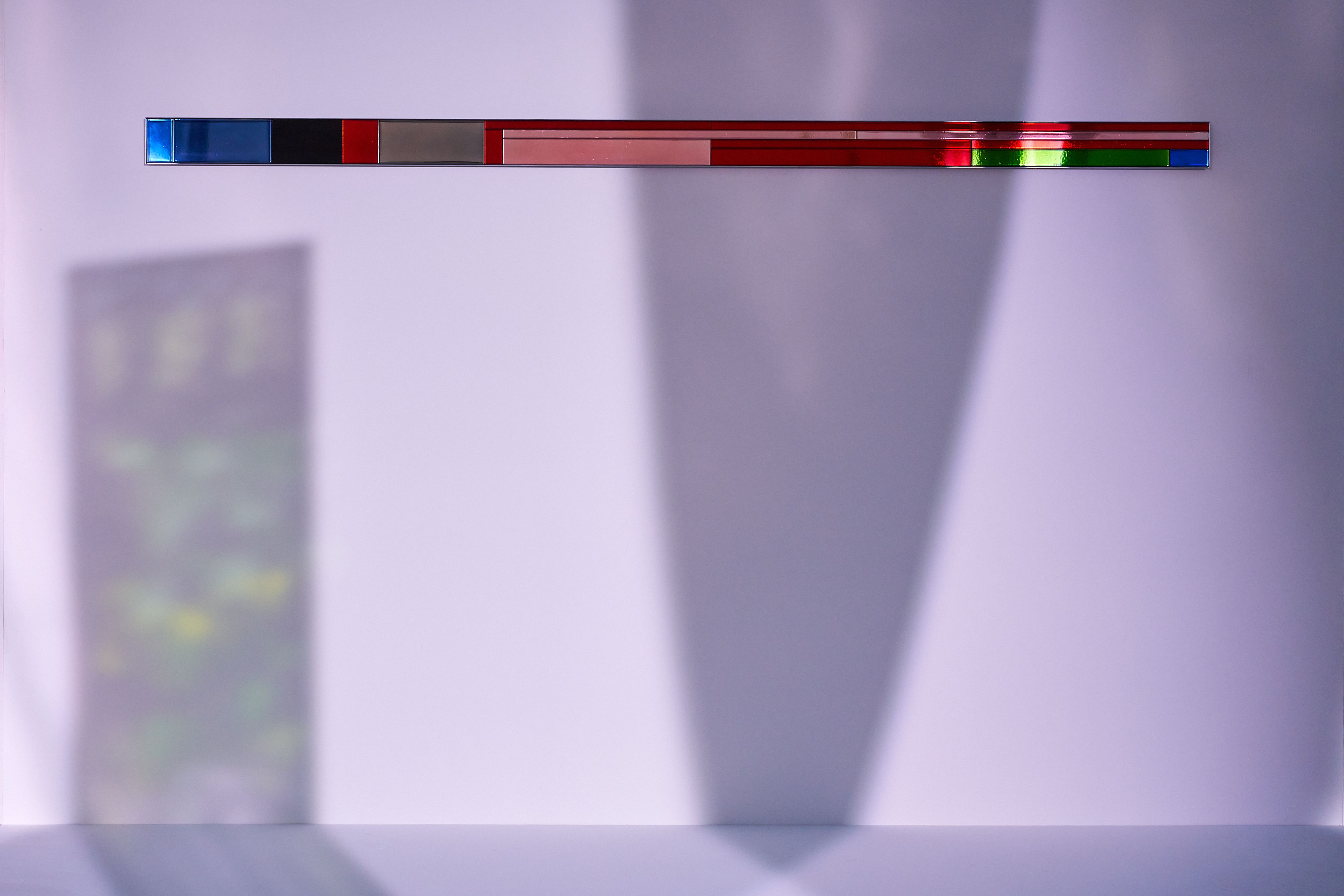

Usually, I pitch the generative artists a project, like the stained glass Optimism sculpture with Jeff Davis, the algorithm-driven tapestry (Navette) with Alexis André, or the mirror series reinterpreting portraits through code (Portraits) with Martin Grasser. But with A Thousand Layers of Stomach — a generative textile installation inspired by the shell-building patterns of clams — it was Alexander Groves of Studio Swine who brought the idea to us. He and collaborators like Aranda \ Lasch are at that perfect intersection of Web 3.0 and traditional design, and those are the people we’re going to work with more and more — producing projects like the generative bistro chair, the handcrafted mirrors based on CryptoPunks’ iconic pixel portraits, and the alternative tapestry series we developed in 2023 with IX Shells, Linda Dounia, and Fingacode. We also have another project with Studio Swine coming up, which will be less of a product and more of an installation to create something more at the intersection of science, tech, and design.

The stained glass sculpture Optimism by Jeff Davis. Courtesy Trame.

The stained glass sculpture Optimism by Jeff Davis. Courtesy Trame.

When you contact designers, do you first identify a company or group that you want to work with, like Maison Drucker or artisans in Morocco, and then find designers that could be a good match for them, or is it the other way around? Do you find designers you really like and then think, “Who could we pair them with?”

Both. With the bistro chairs, I’m friendly with the people at Maison Drucker. And when I talked to Aranda \ Lasch and saw their approach to the craft, it made sense to pair them together. So there, it started with the craftspeople.

Many designers have done custom chairs for Maison Drucker, so it’s not necessarily a novelty to create custom designs, even with these sorts of variations. So what makes this process different? What type of technology does this require?

For the bistro chairs we developed an app with an algorithm through which you can make customizations and output different weaving instructions. An interior designer can create a new pattern or palette of colors, save it, and request a code to send to Maison Drucker, which then produces their chair. It’s straightforward. It’s a tool that augments the ability to generate patterns beyond the usual limits of designers. If you were a designer and I asked you to make as many patterns as possible, you’ll maybe make 20 in one day — at a certain point, you can’t come up with more ideas. But this algorithm can generate countless unique patterns for anything in Drucker’s catalogue.

This is a very banal question: how do your finances work?

We get a commission on every product sold, as with every other gallery. Our collectors are our strength. We have a collector base that wants to collect Aranda \ Lasch, Alexis André, or Jeff Davis, and these generative artists come with their own audience of collectors.

Optimism by Jeff Davis. Courtesy Trame.

Portraits by Martin Grasser. Courtesy Trame.

It seems like by straddling these two realms — Web 3.0 and traditional design — you have to code switch all of the time.

Yes. When I talk to generative designers and artists, or people from Web 3.0, I need to make arguments about why the physical is relevant, why preserving the cultural heritage of craftsmanship is important. When I talk to craftsmen, I need to fully explain why the future is digital, how they will play a part in it, and why they need to play a part in it in order to stay relevant. Because I’m in the intersection of this Venn diagram, the people who are there with me, like Aranda \ Lasch and Alexander Groves, are fucking fabulous. But as soon as you leave that intersection, it takes a lot of energy to bring people there. But I know that intersection is going to be the new normal in the future, and that it’s growing because my conversations get easier every month. Having said that, before I found Bruno Loire, my stained glass partner for Jeff Davis’s Optimism project, I visited three workshops in Paris and had extremely difficult conversations — whenever I talked about generative or digital design, people would shut it down immediately. Bruno comes from a 100-year-old family of craftsmen who restored the Notre Dame, and when I spoke with him, he was immediately interested. It’s a challenging conversation to onboard people, but whenever you meet with the brightest of the milieu, it’s an easy conversation, even if it’s totally different for them, because they have innovation in their DNA. It’s embedded. They’re bored with existing conservation and they want to do something.

Martin Grasser's mirrored glass collection Portraits at Vizcaya in Miami for Art Basel 2024. Courtesy Trame.

In the beginning, were you thinking more about connecting designers with craftsmen — connecting the contemporary design world with ancient craft?

I would say it’s been an evolution, because I’ve always had these new technologies at the forefront, but I was new to the design world. I needed an entry point, and I also needed to understand how it works, what the value chain is, and how to actually create a collection. That’s why I started with something familiar to me — Moroccan crafts — and evolved with one exhibition after another while keeping that innovative approach. For me, the future is digital provenance. Everything we make will be tokenized and off-screen. It’s something that is truly innovative, and it comes with commercial potential. From a business perspective, it’s a unique territory, whereas in the traditional design world, you’re on the battlefield. This is going to be the new normal in a few years.

You look for people that you’re interested in and create this connection with artisans and fabricators. Do you see yourself almost as an agent for generative artists and designers who might love to turn some of their work into physical objects?

I’m not interested in that. We want designers and artists to express their creativity both digitally and physically. I don’t want them to tell me, “I have this digital thing, make it physical.” I don’t do that. I want to be engaged in the development process to make sure that the outputs are good and make sense. We are a collaborative studio. Yes, we’re a connector, and this is new territory, and we’re experimenting and investing. We’re happy to work with artists, design firms, and fairs that are looking for new technologies with traditional or parametric designers, but at the end of the day, the project’s concept needs to make sense and be treated holistically, taking the digital and physical into consideration at once from day one. It’s not going to be someone asking us to make a digital picture physical or make a physical piece into a digital one. There’s a whole process and approach. Otherwise it doesn’t make sense — it’s just fluff.

CryptoPunks' pixel portraits in Marfa, Texas. Courtesy Trame.

Fingacode's tapestry for Trame's Desert Threads collection in Marfa, Texas in 2024. Courtesy Trame.

CryptoPunks' pixel portraits in the desert in Marfa, Texas. Courtesy Trame.