INVISIBLE CARE

The Architecture of Domestic Labor

by India Ennenga

Berwick Street Film Collective, still from Nightcleaners, 1975; film, 90 min. Courtesy Berwick Street Film Collective.

Domestic workers, laboring in private homes and public institutions each day, are usually architecture’s most intimate caretakers — the cleaners who know every inch of every surface by touch, the in-home nurses who have measured the steps from the bedroom to the washing machine, and the nannies who have memorized which drawers fit clothes, toys, or wipes. Their work is carried out quietly and repetitively, only visible when left undone. It is easy to see clean windows, tidy hallways, and sanitized bathrooms as architecture’s natural state, its status quo — but here is what is missing from such a view: the precarity of working without a contract, health insurance, government protection, unionization, or often even legal status; the physical effects of chemical cleaning agents on the body; the children left behind to care for those of another; and most essentially, the human experiences, the rich lives of those who work to make it seem as if the spaces we move through are perpetually spotless. These are the workers who care for our architecture, but for whom architecture cares very little, rendering them invisible at every opportunity, maximizing frictionlessness for homeowners while minimizing privacy, convenience, and autonomy for housekeepers (how telling that homes are owned, but only houses are kept, swept, and tidied up). Architecture — whether on the scale of the city, building, or room — is increasingly in tension with the visibility of domestic labor and laborers.

In her speculative essay Domestic Orbits, architect Frida Escobedo found that many of the architectural plans for Mexico City’s most iconic buildings omit the servant’s quarters entirely. The buildings themselves offer various methods for obscuring the labor of these domestic workers as well — what Escobedo terms “orbits of exclusion” — from service buzzers hidden beneath tables to separate stairwells and even entirely parallel living structures, often lacking in basic ventilation, sunlight, or other necessities. The organization of domestic space is, after all, a labor issue.

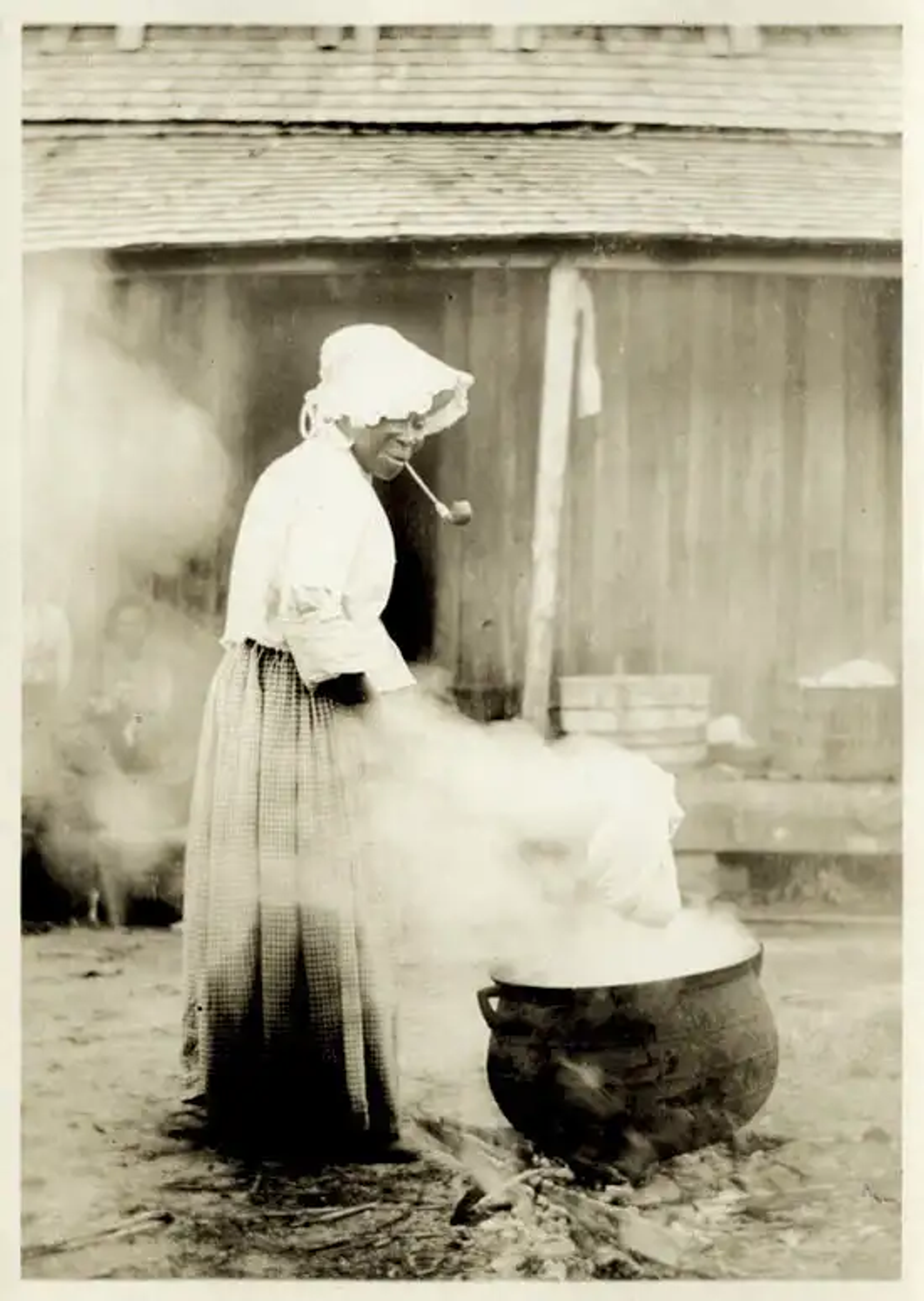

Clifton Johnson, The washerwoman, 1865–1940. Courtesy The Jones Library Inc., Amherst, Massachusetts.

In the U.S., the enduring tension between domesticity and labor can be traced back to the horrors of plantations, where architecture and landscapes were designed to keep enslaved workers under near-constant surveillance by owners, overseers, or even neighboring estates. As researcher Terrence Epperson has argued, Thomas Jefferson and George Mason intentionally designed their plantations as “spaces of constructed visibility,” ensuring enslaved workers felt watched while simultaneously rendering them invisible to Mason or Jefferson themselves, ultimately masking the “less idyllic aspects of plantation life from view.”

In the years following the abolition of slavery, Black domestic workers were at the forefront of collective action, finally able to insist on the visibility of their labor as they formed some of the earliest unions in the U.S. In 1881, the washerwomen of Atlanta organized a strike for better wages and, in the process, created the Washing Society, membership of which increased from 20 to 3,000 over the course of just three weeks. These initial successes were quickly reversed, however, when, as part of the New Deal, the 1935 National Labor Relations Act and 1938 Fair Labor Standards Act were passed with specific exclusions for domestic workers as part of a compromise to secure the votes of Southern Democrats in Congress. These exclusions still leave many domestic workers — disproportionately non-white women — without key protections such as collective bargaining rights, health and safety standards, and in some cases, overtime pay.

It was in response to such conditions that Marxist feminists began organizing and demanding that reproductive and domestic labor (raising children, feeding working husbands, cleaning houses) be recognized as work, as opposed to some fundamental, expected act of care. What suburban architecture meant to obscure was dragged into the light. Artists like Mierle Laderman Ukeles, whose maintenance art involved staging her daily tasks of washing and cleaning as performances within museum spaces, were instrumental in this effort.

The Kitchen Debate, Nixon and Khrushchev at the American National Expo in Moscow, 1959. Courtesy Nixon Presidential Library and Museum.

Yet as middle-class women began moving into traditionally male jobs, much of the nuance and solidarity of the struggle fell by the wayside. Domestic work became further stigmatized as demeaning labor for supposedly unemancipated women — and the poorer, often immigrant workers who took the place of middle- class housewives entering the workplace were rendered only more precarious. Critiquing Betty Friedan’s 1963 Feminine Mystique, the author and theorist bell hooks points out that Friedan “did not discuss who would be called in to take care of the children and maintain the home if more women like herself were freed from their house labor... She did not tell readers whether it was more fulfilling to be a maid, a babysitter, a factory worker, a clerk, or a prostitute, than to be a leisure class housewife.”

In the postwar U.S., however, it was middle-class housewives who became the center of the debate around rights and domestic work, quickly monopolizing political energy. The technological advances of suburban living in the 1950s promised an end to the need for domestic workers. Washing machines, kitchen appliances, and vacuum cleaners were sold as guarantors of domestic autonomy, even as the planning of such suburban spaces trapped homeowners in greater isolation and gave them entirely new maintenance work to perform — individual lawns needed weekly mowing, grocery stores took long drives to reach, plumbing required repairs and floors washing. The supposedly liberatory consumerism and individualism of the West thus combined to transform the home into a means of containment.

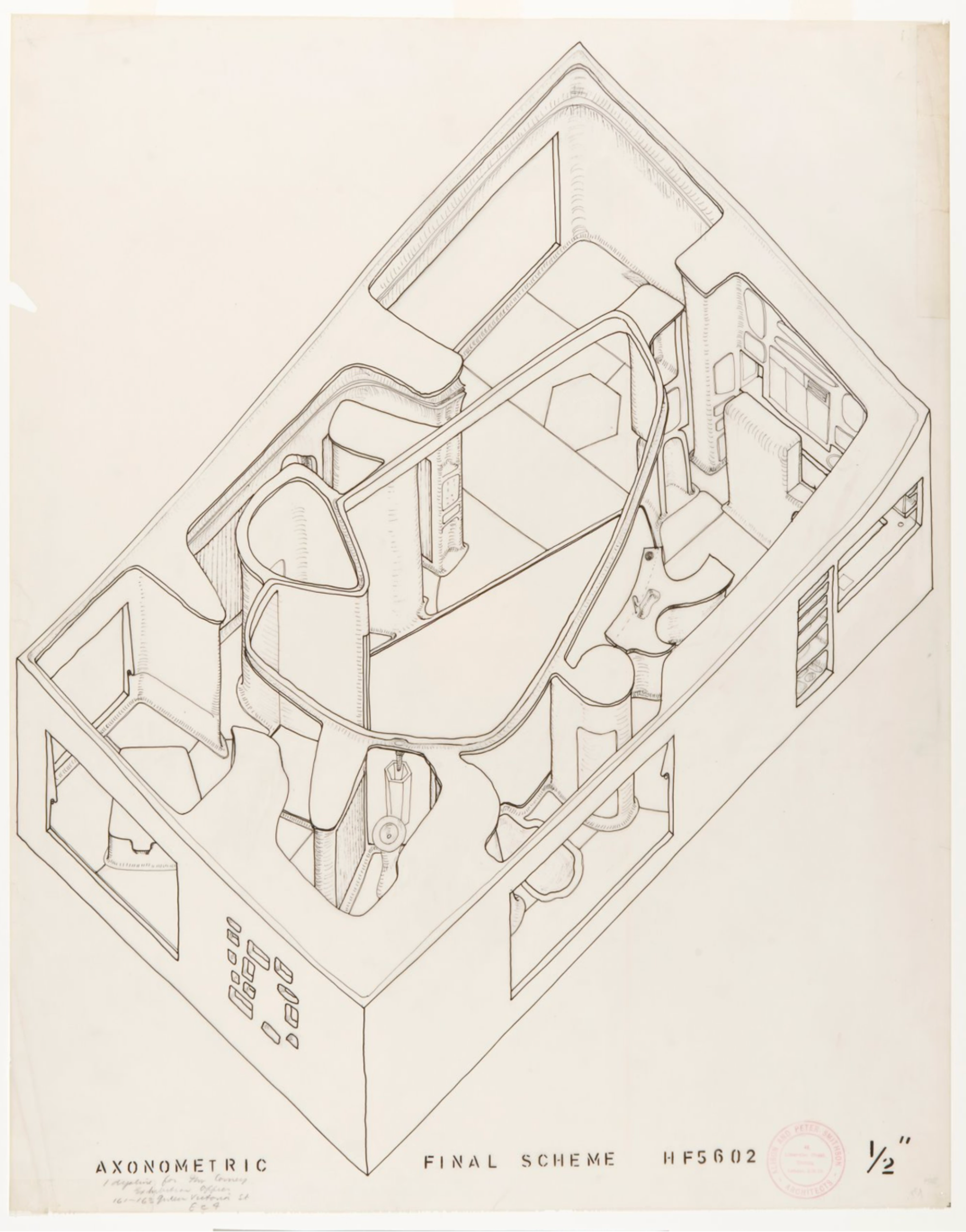

Model homes (often sponsored by cleaning brands) proliferated in the U.S. and U.K., displaying all these modern “conveniences.” Peter and Alison Smithson’s House of the Future, a speculative design for the 1956 Daily Mail Ideal Home Exhibition, took this domestic technology to an extreme. Its interior walls are continuous, every corner is rounded for ease of cleaning, and the sunken bath’s automatic rinsing system eliminates any porcelain-scrubbing. The Smithson’s idealized architecture invokes its ideal residents: childless, mess-less, pure-itanical. Like much of Modernism, the House of the Future mistakes cleanliness for perfection: cleaning is understood as a kind of mechanical sanitation that can be automated rather than something that requires a continuous engagement between architecture and environment, domesticity, and conviviality. As feminist scholar Helen Hester sums up this contradiction of the modern psyche: “There is no room for care in a space where everybody is care-free.”

Smithson, Alison (1928-1993) and Peter Smithson (1923-2003). The Alison and Peter Smithson Archive. House of the Future, Axonometric: Final Scheme. Courtesy of the Frances Loeb Library, Harvard University Graduate School of Design.

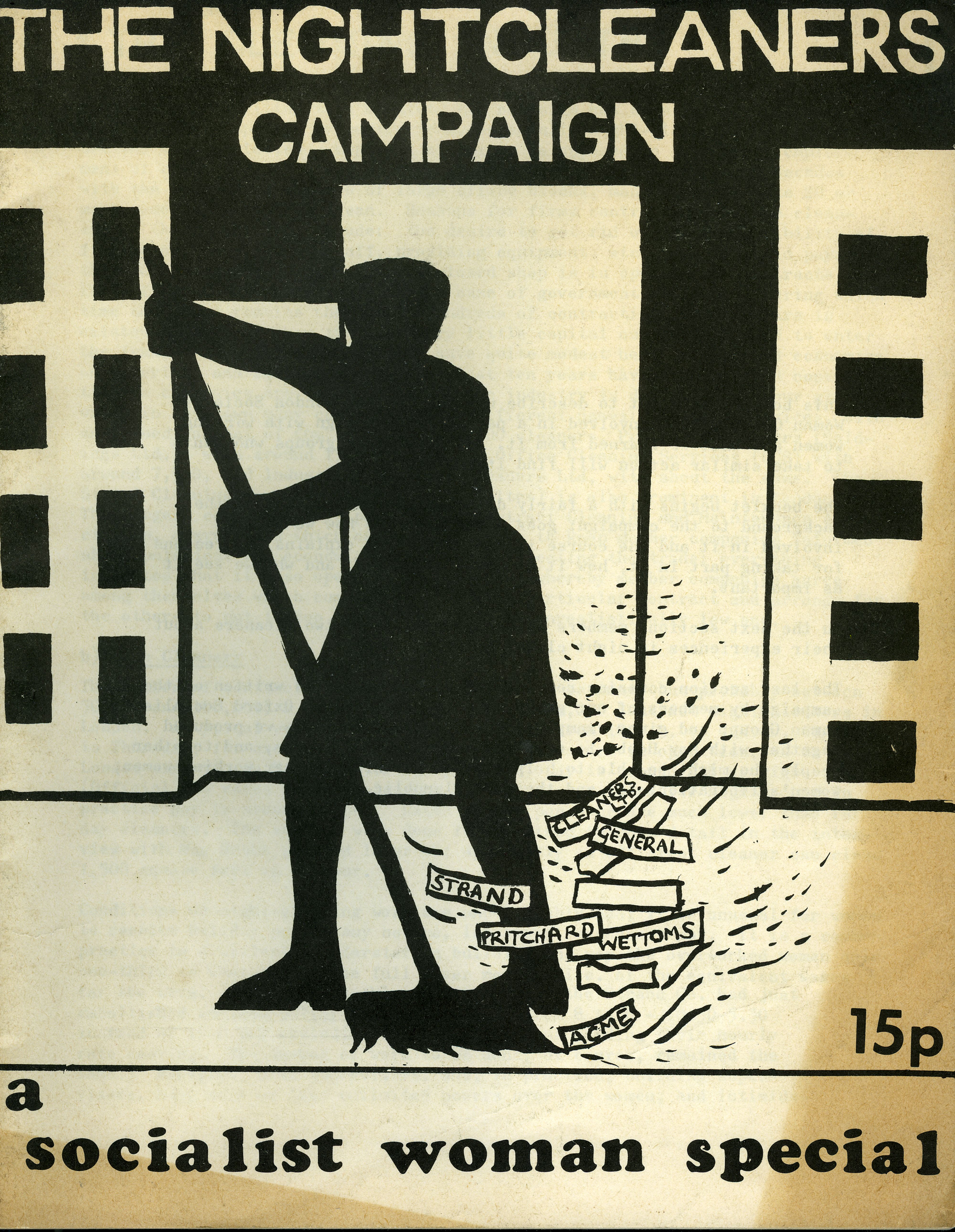

In the U.K., the Berwick Street Film Collective captured the double bind of impoverished workers who found themselves taking on their own personal housework and professional domestic work in their 1975 avant-garde documentary The Nightcleaners. Following a group of cleaning women turned union activists, the film depicts the various kinds of invisibility these workers face, from the personal to the political and even quite literal — as one of the cleaners explains, because she works the night shift, she hasn’t seen her employer in the last five years of working for him. Another adds, “If I do get some sleep, it’s between one and three [pm]. If I can get any. If the baby goes to sleep.” This statement is followed by a strip of blank tape, prompting viewers to reflect on how this is possible, how this is allowed to happen. Yet it is perhaps The Nightcleaners’s iconic shot of a nondescript, modern office building after dark that strikes the greatest chord. One window is illuminated, then darkened again, as another flickers into light. Cleaners are moving from room to room, but all that we see are the little anonymous squares of glass behind which they work.

The corporate employees of the office building are deemed productive, busy, visible, while the cleaners who work there at night are replaceable, informal, erased. As political theorist Françoise Vergès has pointed out in her essay “Capitalocene, Waste, Race, and Gender,” a divide is formed not only along class lines but racial ones as well. “The working body that is made visible,” Vergès writes of white-collar consumers and laborers, “is the concern of an ever growing industry dedicated to... cleanliness and healthiness,” while the “other working body,” the domestic laborer, “is made invisible even though it performs a necessary function for the first: to clean spaces in which the ‘clean’ ones circulate, work, eat, sleep, have sex, and perform parenting... Women of color enter the gates of the city, of its controlled buildings, but they must do it as phantoms.”

Berwick Street Film Collective, still from Nightcleaners, 1975; film, 90 min. Courtesy Berwick Street Film Collective.

It is precisely this tension between public spaces and institutional invisibility that artist patricia kaersenhout explored in her 2016 performance piece The clean up woman at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam. Dressed as a member of the Stedelijk’s cleaning staff and carrying a broom, kaersenhout set out to show “the relation between power dynamics and invisibility within white institutions,” noting that “the occasional black spots in this museum, represented by security, catering personnel, and cleaners” reminded her of Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man (1952), in which the protagonist’s job “is to mix the [white] paint with one drop of black paint in order to make it look more radiant white.” At the end of the performance, kaersenhout was shocked beyond her own expectations upon hearing that her friends and colleagues had literally failed to recognize her as she swept the floor in front of them. The simple act of cleaning made her invisible.

This is the contradiction of so much modern and contemporary architecture: the supposed transparency of minimalism conceals more than it reveals. Stone and steel seem born anew each morning, while the hands that make this so remain obscure. Jeff Wall sought to draw out a similar tension when commissioned by the Fundació Mies van der Rohe to photograph the Barcelona Pavilion. Wall captured something akin to a portrait of the space with his photograph Morning Cleaning, which showed the necessary daily maintenance behind the building’s iconic appearance. In the image, the meticulous placement of van der Rohe’s furniture is upended, and a window drips with sudsy water as a laborer prepares to squeegee the glass — the daily labor ironically needed to maintain its veneer of simplicity revealed.

For the 1986 Milan Triennale, Rem Koolhaas reconstructed the same Barcelona Pavilion as Casa Palestra: a space in which Modernism and “physical culture” might interact. Staged performances featured actors exercising, using the bathroom, or carrying out other quotidian tasks in an attempt to wrest Modernism from the uninhabited, non-corporeal sphere. In his essay, “Miestakes,” Koolhaas dedicates a short section specifically to cleaning, reflecting on his own repetitive maintenance work in the pavilion and the complicated feelings such an intimate task engendered. “I do not respect Mies, I love Mies,” Koolhaas writes. “I have studied Mies, excavated Mies, reassembled Mies. I have even cleaned Mies. Because I do not revere Mies, I’m at odds with his admirers.” It’s precisely this oscillation, between love and disdain, the visual pleasure of such a design and the pain of its invisible maintenance, that most visitors to the Pavilion might miss. Koolhaas’s understanding, even ambivalence, comes from his labor, the familiarity of closeness and touch that it created. Caring can engender love but rendering that care invisible destroys admiration on a systemic scale.

Berwick Street Film Collective, movie poster from Nightcleaners, 1975; Courtesy Berwick Street Film Collective.

The invisibility of domestic laborers is structural — built into our cities, laws, architecture, and economy — and plays out across everything from the design of apartment complexes in which maids’ rooms are located behind the kitchen or laundry and away from windows, guests, or doors to the urban plans that place affordable housing on the outskirts of neighborhoods and away from city centers, requiring long commutes at the brink of dawn or in the dead of night. Meanwhile, the public institutions where socialization and community are meant to flourish similarly ensure that maintenance happens out of sight or after hours. Even the ever-growing digital architecture of gig-work apps perpetuates such invisibility, rendering the people who provide services as mere avatars with ratings, never repeating and ever-replaceable. Workers become largely invisible not just to customers, but also to one another, and even to themselves — their labor deemed “informal” and their job titles nonexistent.

In Wages Against Housework—Silvia Federici’s 1975 book on feminism, reproductive labor, and the need to reenchant the world in the face of capitalism — the scholar and activist argues for a resocialization of domestic work. She imagines an architecture that creates room for communal labor — not the failed experiments with low-income housing estates like Robin Hood Gardens (the Smithsons again), but spaces that echo a more foundational, time-tested way of working together: a commons against and beyond capitalism. Federici points specifically to the prewar village washing basins in Italy and the contemporary markets in many areas of West Africa. It is in these spaces, she claims, that labor, socializing, and thus mutual visibility become possible. We might think of such structures — alongside shared childcare, community baths or pools, parks, and open kitchens — as public, rather than private, luxuries.

When asked how architects might reimagine apartment complexes, like those she investigated for her case study in Mexico City, with domestic laborers in mind, Escobedo said she pictured a large building where employees had private apartments of the same beauty and functionality as their employers. A shared daycare on the ground floor would allow nannies to pool together, watching their own and their employers’ children simultaneously. Communal areas within the complex would act as social spaces, where all residents might mingle, build community, and ensure mutual visibility. Just like Federici, Escobedo sees resocializing as an antidote to invisibility, asking not just who cares for architecture, but how architecture might help structure care.