INTERVIEW: Yussef Agbo-Ola and an Architecture of Ecological Systems

In an essay titled “Remaking Social Practices,” philosopher Felix Guattari asks: “By what means, in the current climate of passivity, could we unleash a mass awakening, a new renaissance?” Artist, anthropologist, and architect, Yusef Agbo-Ola’s conceptual practice answers Guattari’s call for mass awakening and renaissance in architecture by looking to many disciplines including art, environmentalism, material science, and anthropology to reimagine architecture as a practice that connects both human and non-human life. What might architecture look like if it were inspired by the unseen? If one looks to microbes, microorganisms, natural systems, and adopts ecological harmony or equilibrium as a way to inform design thinking? Answers to these questions might result in, as Agbo-Ola posits, architectural pavilions made from biodegradable materials, tensile structures sensitive to temperature changes, sensory experiments that connect cultures, and building amphibious houses that can adapt to rising sea levels.

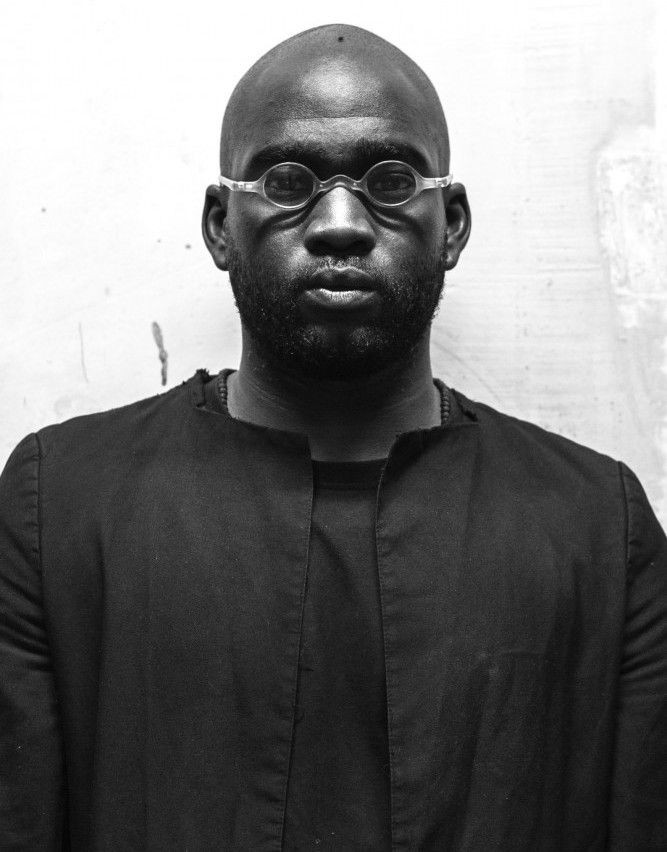

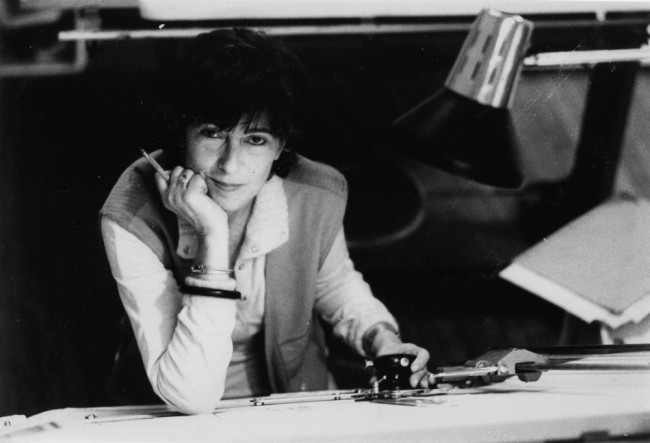

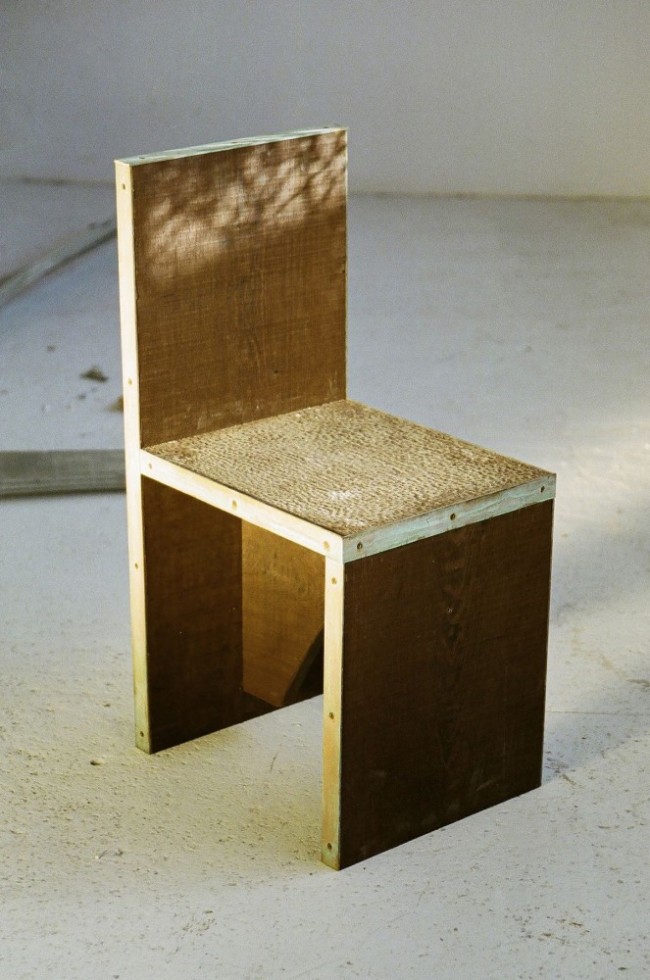

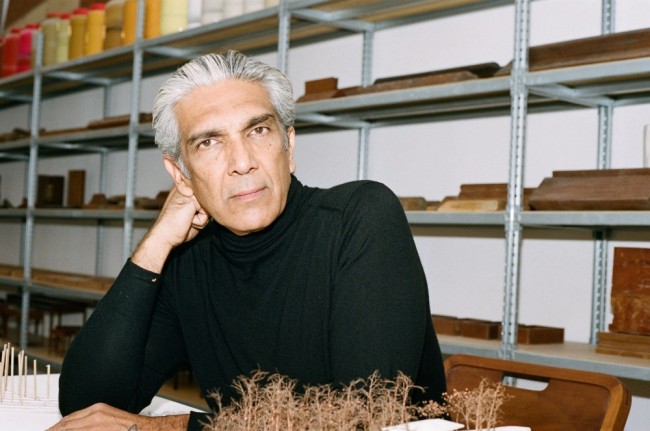

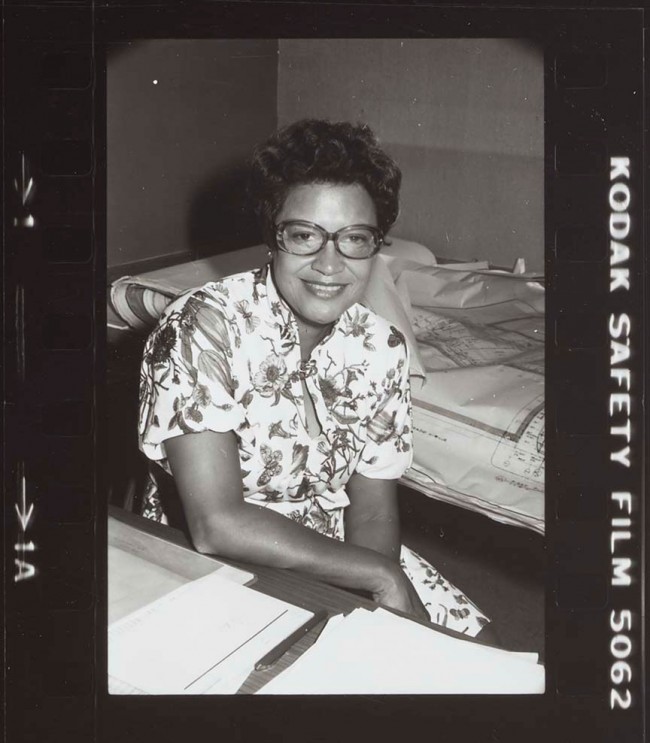

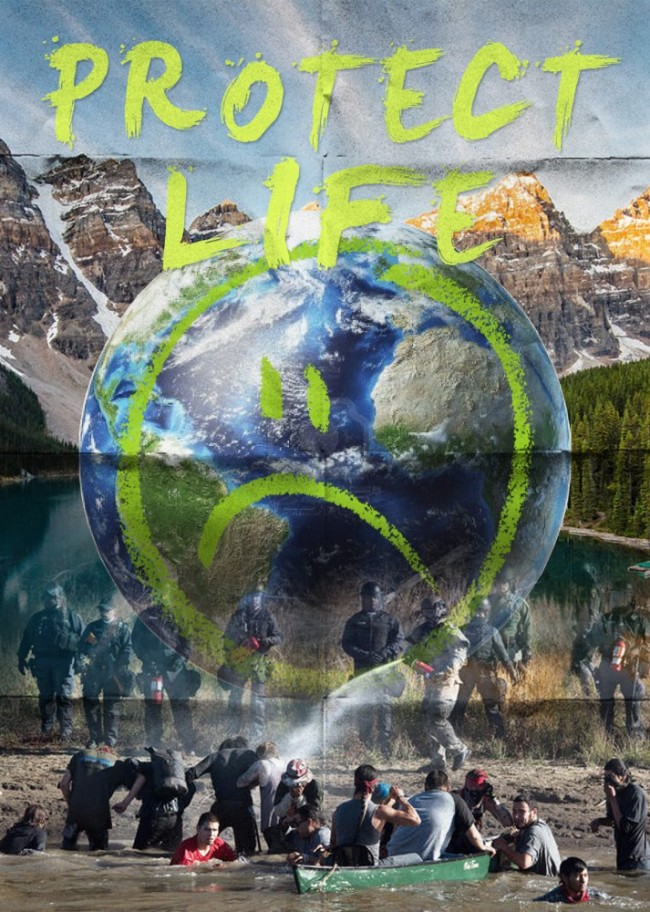

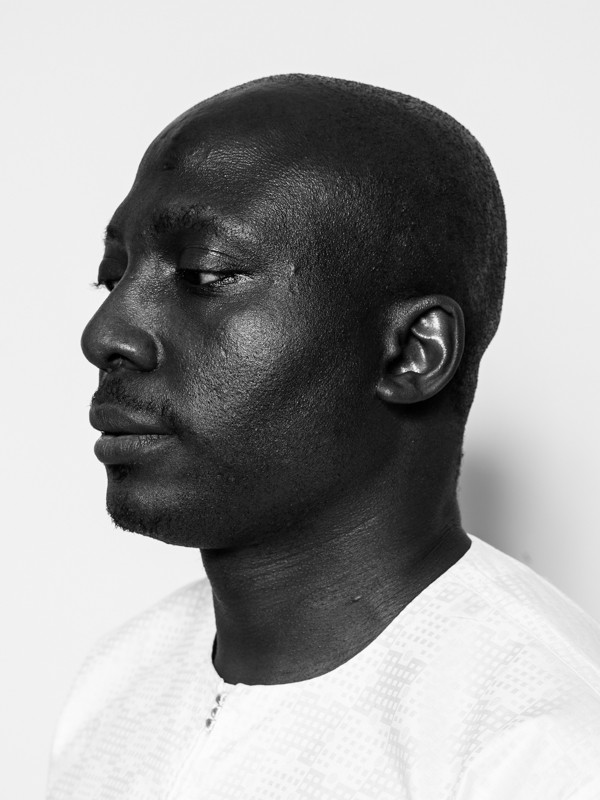

Yussef Agbo-Ola. Image courtesy of Olaniyi Studio.

Born in rural Virginia in a multi-heritage Nigerian, African-American, and Cherokee household, Agbo-Ola’s interest in natural systems and nature began at a young age, fueled by a curiosity in observing his surroundings. This led to an anthropology degree at Virginia Commonwealth University, followed by an Art & Design BFA at Virginia State University and an MFA at Wimbledon College of Art, and finally, an MA in Environmental Architecture at Royal College of Art London. Since graduating, Agbo-Ola has been based in London where he established Olaniyi Studio, a multidisciplinary design studio aiming to expand environmental awareness that works globally with artists, scientists, institutions, design students, architecture studios, and rural communities. In this conversation for PIN–UP, Agbo-Ola discusses how architecture can live among the complexities of ecological systems. He imagines designing for a future he hopes that will inspire more aware environmental perspectives and values of care towards the world we live in.

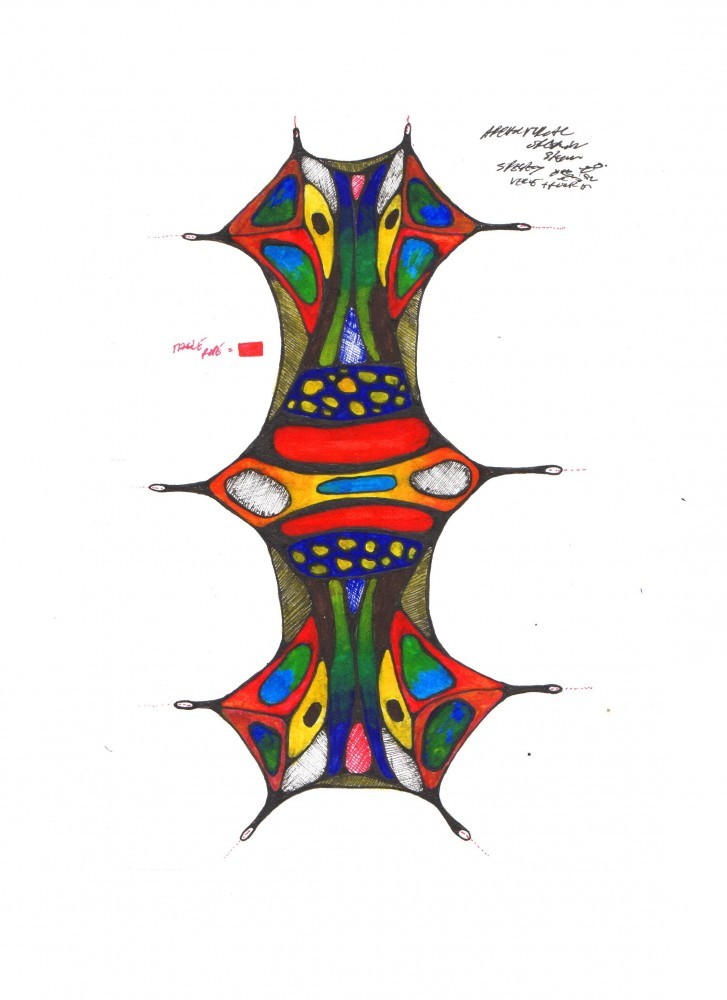

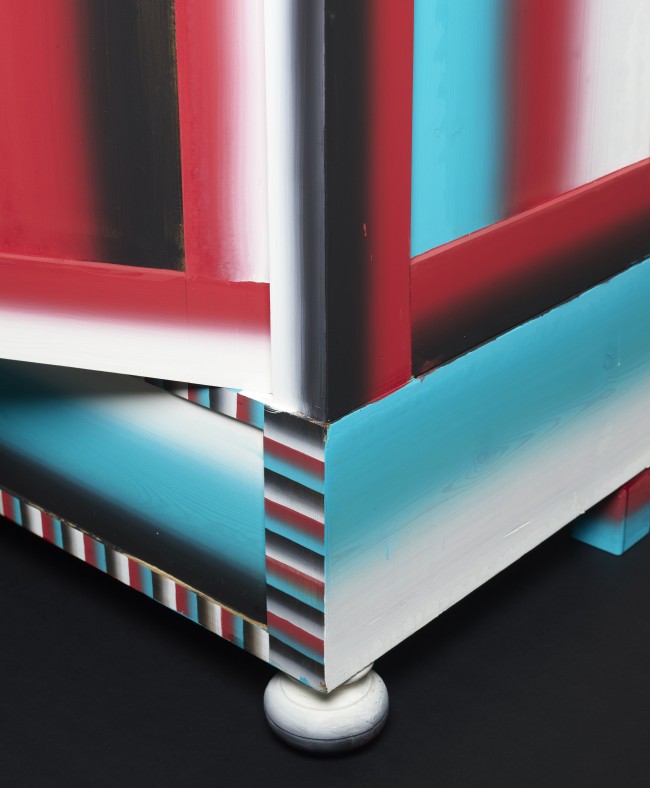

AROMATIC MEMORY Architectural Skins - Amazon Jungle, SKIN DNA = Passion Flower Extract + Blue Poison Frog Dye + Pond Sand. Image courtesy of Olaniyi Studio.

Jareh Das: Your practice spans art, environmentalism, architecture, anthropology, agriculture, and material science. What led to your working across so many disciplines? How has that helped you include nonhuman aspects such as microbes and plant material in your practice?

Yussef Agbo-Ola: The world for me is an interconnected system. It will shatter if there is a state of metabolic imbalance. With this in mind, my interests stem from a childhood spent in a small American-Indian village called Chuckatuck in the city of Suffolk, Virginia. As a child, in this isolated region, I found myself constantly being inspired by its quiet landscape, its forests and rivers. I remain humbled and inspired by Chuckatuck. The architecture of ecological systems and the way these systems create biodiversity of life, forms, symbols and scales of beauty informed my beginnings as an artist and architect. It is through this lens that I began material science experimentations, as a conceptual framework for living architecture. I learn from and am in service to nature, with its nonhuman organisms as my most important clients.

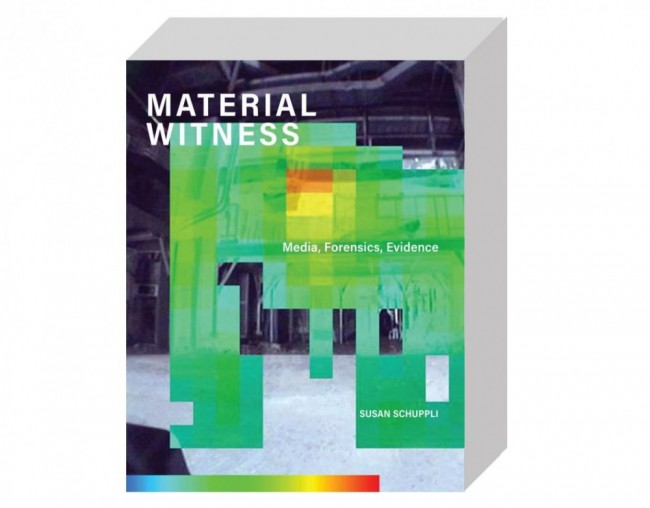

Architect as Shaman book (front cover). Y. Agbo-Ola, 2018. Image courtesy of Olaniyi Studio.

With such a wide-ranging disciplinary approach and a highly conceptual design practice, what are your views on the ideological or disciplinary challenges within architecture that prevent coming up with new solutions to environmental problems?

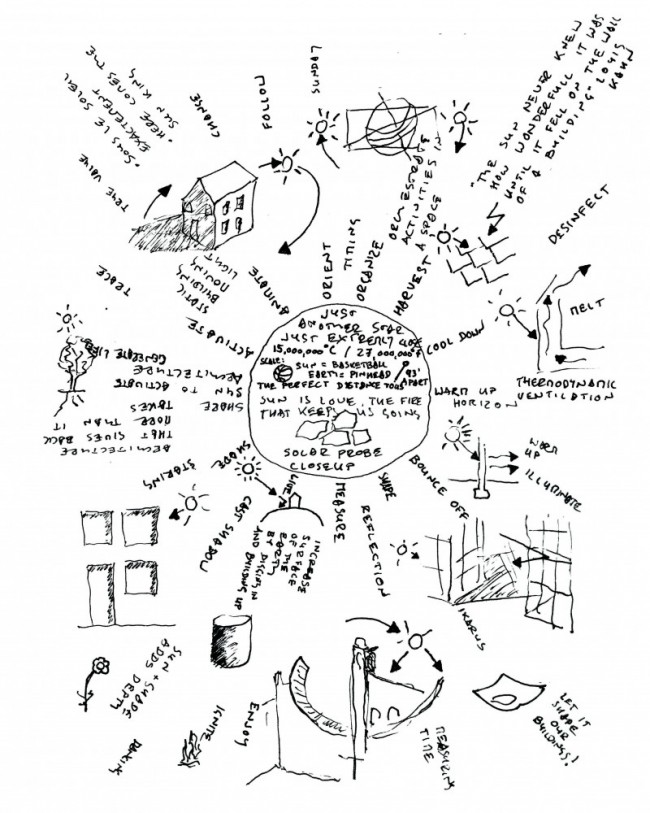

Earth is a beautiful living organism always at work to replenish itself and produce life through decay and regeneration, a constant network of environmental relations. I find it quite challenging to pinpoint a single, or rather, most important environmental concern when it comes to the ways in which we have altered, worked against, or totally forgotten how to work within the externalities of our cultural perspectives towards the environment. I can, however, say that in relation to architecture, I deeply believe that the environmental challenges of the profession require new environmentally-led perspectives. Environmentalism in architecture still sits within the boundaries of designing for climate comforts. It is my deep conviction that this way of thinking limits architects. It’s true that culturally speaking, we need to consider geographical weather fluctuations, climatic systems, and internal comfort but I feel as though in regard to environmental challenges, these are all just on a surface level. Additionally, we should all be considering the beauty of decay and architectural structure as a living apparatus that is also allowed to die and transform just like seeds do with the right soil chemistry. This is poetic architecture.

There is a long ideological history related to the ways humans control both the environment and Earth’s systems instead of understanding design as collaboration within them. I need to highlight in my view that this is mainly tempered within a Western perspective of architecture for protection from the environment. While I consider shelter as an essential need, I feel we are doing architecture an injustice as a practice wholly centred on this narrow aspect of design. Instead, I propose an architecture that forces the architect to surrender, be humbled by, and learn from the elegance in the ambiguities of Earth’s systems through design by collaboration.

What are the benefits of an interdisciplinary approach, especially in light of the different political, social, economic, and ecological implications of design in this time of climate crisis?

When we segregate expertise, research, belief systems, and ideas into sub-divided categories of intellectual supremacy, the vicissitudes between us becomes our current reality. It is not that we need to all be jacks of all trades but rather, we need an attitude of openness adopted by designers and all the supporting fields. My life’s work will be to continue to grow and lead a studio that is full of non-designers, non-architects, non-intellectuals, a studio where all fields are fused together. Ecologists, healers, farmers, anthropologists, etc. all conversing and experimenting with one another. Design for me has never been an act of simply producing a product or artefact but involves the act of designing environments and systems of relations that bring people together to rethink how their expertise can create a new reality for the whole.

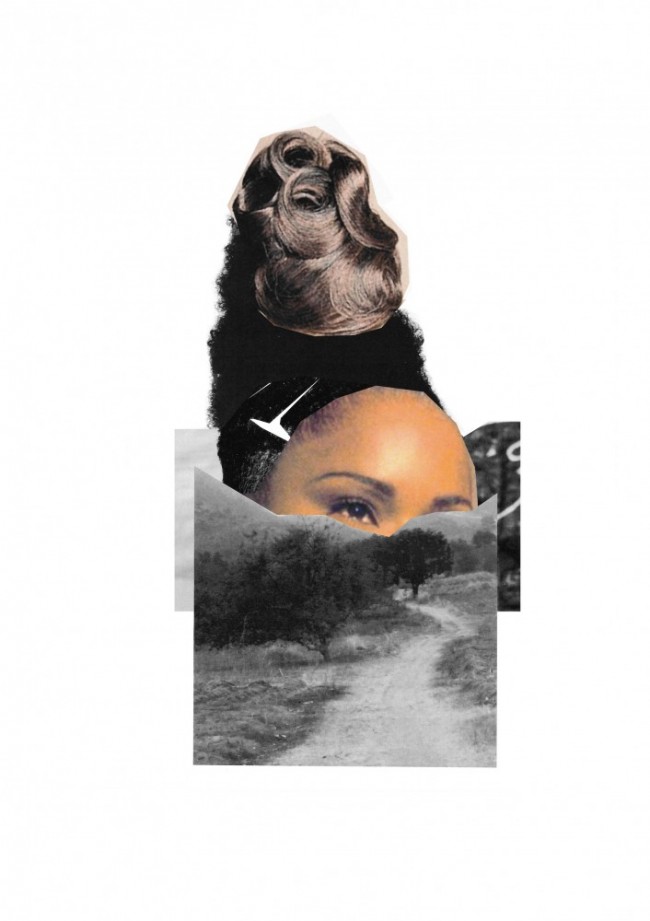

Artist + Anthropologist = Nigeria, (Internal Pages). Y. Agbo-Ola, 2018. Image courtesy of Olaniyi Studio.

Senses often seen as being outside architectural terrains such as sounds and aromas are a prominent feature in your work, such as in PLANT CELLULOSE SKINS + AROMATIC MEMORY = AMAZON JUNGLE. Could you expand on bringing the senses and sensory engagement into architectural and design thinking?

The senses ground us to environments and extend moments of experience. The PLANT CELLULOSE SKINS + AROMATIC MEMORY = AMAZON JUNGLE project questioned the ways an environmental architectural experience can be extended based on a system of isolating and enhancing our sense of smell through material science. Through these artefacts, a series of plant and animal scents from different locations in the Amazon Jungle were frozen in cellulose architectural skins creating a spatial and multi-sensory environment that allows humans and nonhumans to question and experience new sensory relations based on the arrangement of a structural apparatus. Often, the sense of smell is the most powerful sense when one is experiencing a new environment. The smells of an environment are deeply rooted in your mental archive, and when you smell something similar to that environment your glands are activated, and you visually picture your experience in a specific place. I wanted to question how smell could be used in a new way to bring us closer to an environment’s wisdom and creative expression, past its visual attributes which can at times be the primary focus of how architects think about the environmental experience.

A quiet observing as a research method. How important is this to your artist + anthropologist experiments, which explore how humans connect with diverse natural environments across different geographical locations in Nigeria, Dominican Republic, Puerto Rico, Chile, Morocco, and Haiti?

Yes indeed, a quiet observing is more than a research method for me, it's a way of listening with the eyes. The artist + anthropologist work is about capturing the sounds of a place with the eyes, and one has to be quiet visually to listen to that geographical region. This series of works takes on methods from what I call experimental journalism. When travelling to these places my aim is to become empty so the place can speak to me through its built structures and cultural beliefs. I make it a priority to allow the people, plants, buildings, textiles, mountains, landscapes, etc. to educate me through the duration of the journey, and after that, the publications are edited and composed, not the other way around. I'm not looking for a story to have a list of pre-ordained logistical plans that dictate the ways in which I observe that place. These works are connected to my life work of building an experimental photographic archive of different regions that also informs Olaniyi Studio’s visual culture archive for design research. This year we will quietly observe Guatemala, Belize, and Madagascar.

AROMATIC MEMORY Architectural Skins - Amazon Jungle, SKIN DNA = Fermented Soil + Monkey Brush Leaves + Iron Extract. Image courtesy of Olaniyi Studio.

Your project and book Architect as Shaman is situated within non-Western and Indigenous practices. Does including “shaman” in the title point to, or imply a healing role in architecture?

Yes and no. I believe architecture can heal, not only people but also landscapes and environments that have been destroyed by humans and anthropological mental systems of environmental neglect. Architecture can catalyze healing through togetherness, separation, its fruit, presence, atmosphere, smell, and many other elements. In addition, I believe architecture can be a place to create room for internal healing as well that does not require the visual stimulation of actually viewing any of its aesthetic qualities, rather it acts as a womb for such an experience to occur, through silence, laughter, crying, or dreams, etc.

However, I would have to say no in regard to the assumption that including the word “shaman” implies themes of healing. From my understanding and anthropological fieldwork, shamans are not in the business of healing, but rather in the business of transformation. The goal of the shaman is not to heal a person but rather to work with the external environmental elements and the internal environmental elements of their subject to stimulate a healthy balance between the two. When there is an equilibrium or balance between the two, one may say they are healed, but the shaman’s intention was to simply restore balance. So for me, I thought that was a beautiful way to think about my role as an architect in relation to designing with the intention to transform the experience of architecture through restoring an environmental awareness or balance through design.

ARCHITECTONIC ENVIRONMENTAL CERAMIC PANELS, Black Iron Clay + Basalt Silica + Fermented Potassium Powder + Red Mica. Y. Agbo-Ola 2019. Image courtesy of Olaniyi Studio.

You mention architectural pavilions a lot in your proposals and writing. Why pavilions as building types?

Architecturally, for me, the pavilion is something that is not necessarily a residential or an inhabited structure built for living. It is community-based and it can range across different scales, which is very important to me. The pavilion can also be something that isn’t necessarily just for humans. It can be a nonhuman pavilion for plants and animals too — whether elephants, fish, squirrels, and so on. The pavilion doesn’t have a dictated demographic of inhabitation. That’s the first way.

Secondly, the pavilion architecturally speaking always has experimental, poetic, creative, testing qualities to it. It can be an experiment. I see it as an artwork injected with the architectural program of experience. It’s something that can be experienced externally by viewing it, or something one moves between, inside. I also see pavilions as something that can decay over time and can be transported to other locations. I like this idea of the decay of a pavilion based on material use, returning to soil or land, and the fact that it can be taken apart, moved, adapted, and reassembled elsewhere.

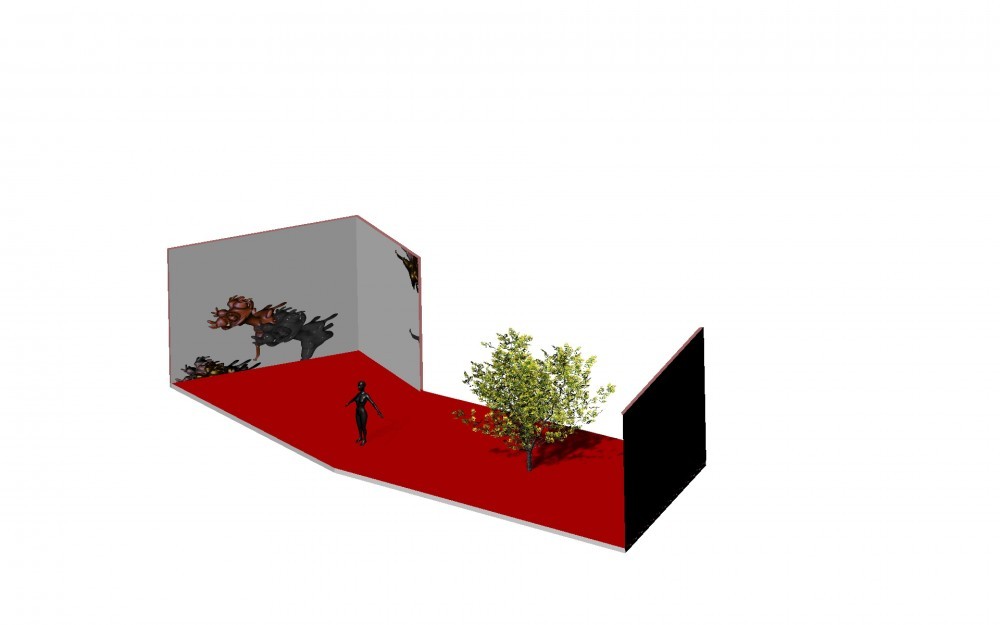

Interior FABRIC Print SERIES X4RiiU, Digital C-Print.

Image courtesy of Olaniyi Studio.

How do your practices as an artist and as an architect and designer with Olaniyi Studio relate? And what new work are you embarking on?

My art practice is about pulling people together to create and question as well as indicate research themes. I’m also painting, cooking, working with chemistry, photography, design, and composing experimental sound. My practice, however, does run separately and in parallel with the studio. At the moment, the studio is based in London. I hope to evolve a nomadic model that can operate in different global locations. Since the work spans research in other countries, it is common for us to stay for a few months and deeply connect to places where we work. Olaniyi Studio’s 2021–22 vision is to open another research base and farm in Nigeria that will produce a collection of artefacts and materials for a homeware and garment line. We’ll collaborate with an indigo farm to produce the dyes we will use for the garments which revive the fading Nigerian indigo dying techniques. It is integral to our studio’s core values to treat our rural and urban work with the same intensity.

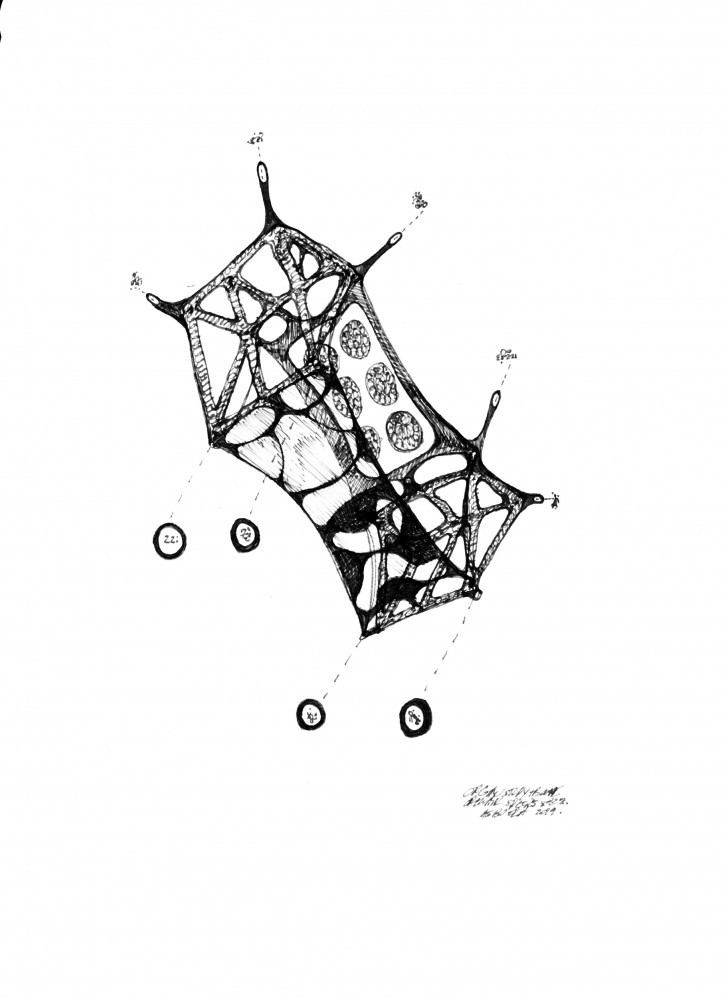

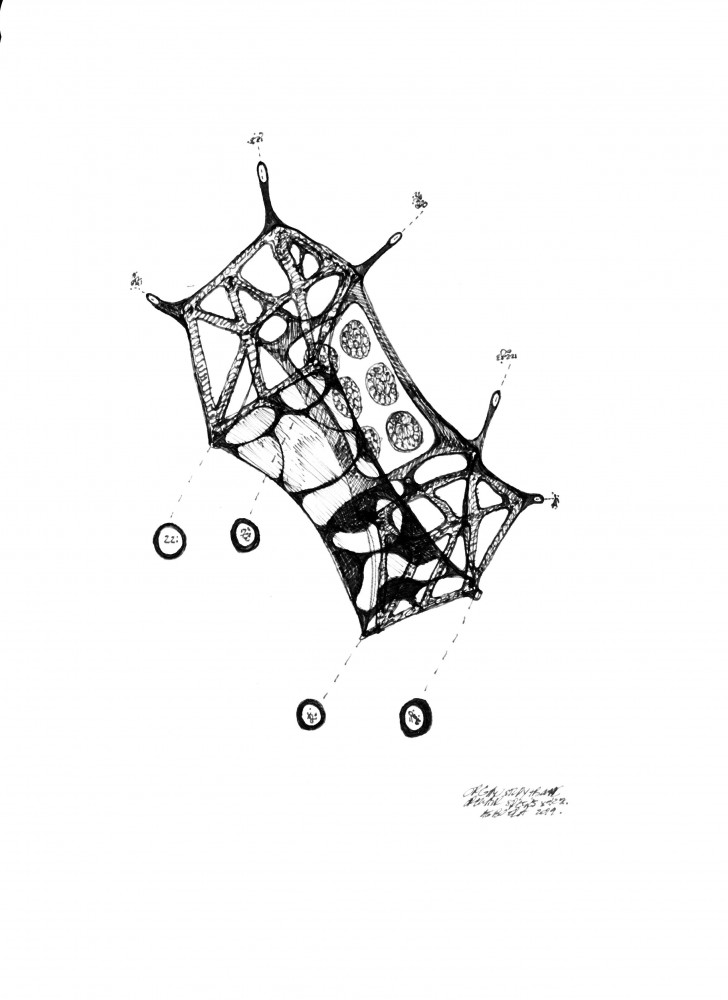

TENSILE SKIN AS MEDICINAL PLANT APPARATUS, Architectural Bone Species (9.096xi). Black Indian Ink. Y. Agbo-Ola 2020. Image courtesy of Olaniyi Studio.

How do your multidisciplinary interests affect how you address environmentalism and environmental activism through architecture and design?

Environmentalism in my view is not solely about energy, waste management, solar panels, and so on, and to be completely honest, there are many people already working with these themes. My approach to environmentalism is grounded in the unseen relations of spatial experience in diverse anthropological and ecological environments. What I mean by this is that I don’t believe that environmentalism can be spoken about unless the person has looked at the ways in which they experience the environment from an internal space. Rather than focus on solutions that try to harness natural energy in new ways or re-greening spaces, I am focused, through art, design, and architecture on questions related to our sensory relationships and to environmental elements. If you see a river as a living being, culturally, then there is a higher chance that perhaps you will not pollute it. If we were to connect my practice to a specific form of environmentalism, I would say it is centered on designing within the mental ecology of society to restore environmental awareness and values through art, design, and architecture.

Interview by Jareh Das.

Images courtesy of Olaniyi Studio.

Jareh Das is a curator, writer, and researcher based in Nigeria and the UK. She holds a Ph.D. in Curating Art and Science from Royal Holloway, University of London for her thesis Bearing Witness: On Pain in Performance Art (2018).