SHAPED BY CULTURE: Ceramicist Zizipho Poswa Embraces the Past Through Large Scale Works

Zizipho Poswa, Ukhula 2, 1 (2018); Glazed stoneware.

Working from Cape Town, South Africa, 39-year-old ceramic designer Zizipho Poswa has taken inspiration from her rural past to produce large-scale sculptures that speak of struggles, success, and a traditional way of carrying water. Through color, texture, and form she manifests cultural Xhosa practices and contrasting ideas in contemporary pieces that are making their international debut this year at both the Salon Art + Design in New York and Design Miami. Poswa speaks to us from the remote village of Idutywa in the Eastern Cape province of South Africa, where she’s participating in a family gathering, and reconnecting with the basic things in life that have inspired her work.

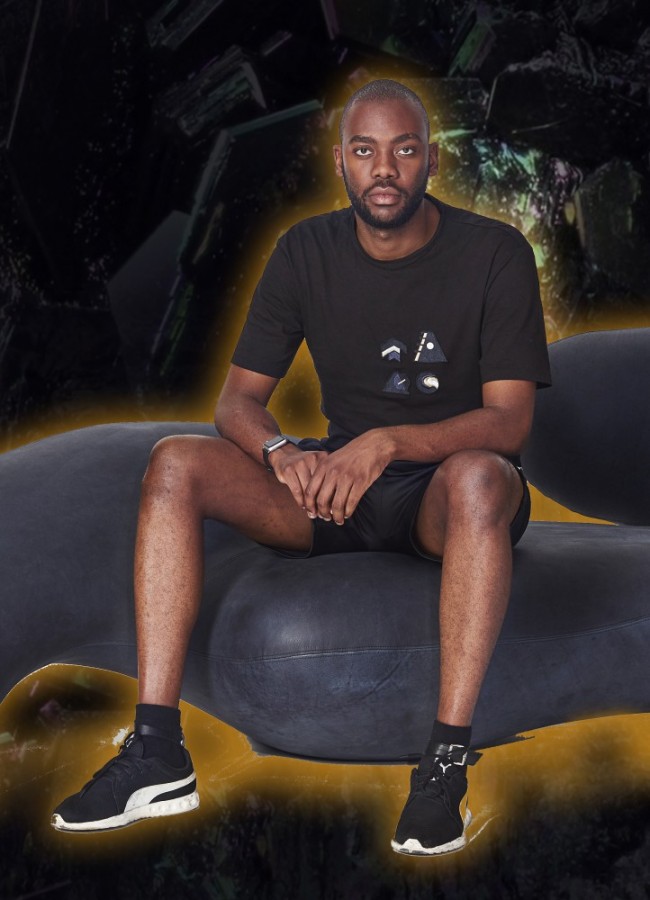

Zizipho Poswa photographed by Richard Keppel-Smith

Zizi, you weren’t always a ceramicist. You started off as a textile designer, right?

Yes, I first worked with textiles, learning the skills of hand-painting, color mixing and pattern-making, which have all served me well in my ceramic practice. I don’t use any transfers, so all my work is hand-painted.

What prompted the move to found Imiso Ceramics with your college friend Andile Dyalvane, a world-renowned ceramicist in his own right?

I always believed I would work with ceramics at some point, as it had been difficult to choose between textiles (which I majored in) and ceramics at college. Andile and I wanted to start a business where he would continue his ceramic work and I would design textiles, but textile production needed more studio space than we could afford, and specific machinery, so ceramics was an easier medium. We opened Imiso Ceramics at the Old Biscuit Mill in Cape Town’s Woodstock district in 2006 and have been there ever since.

-

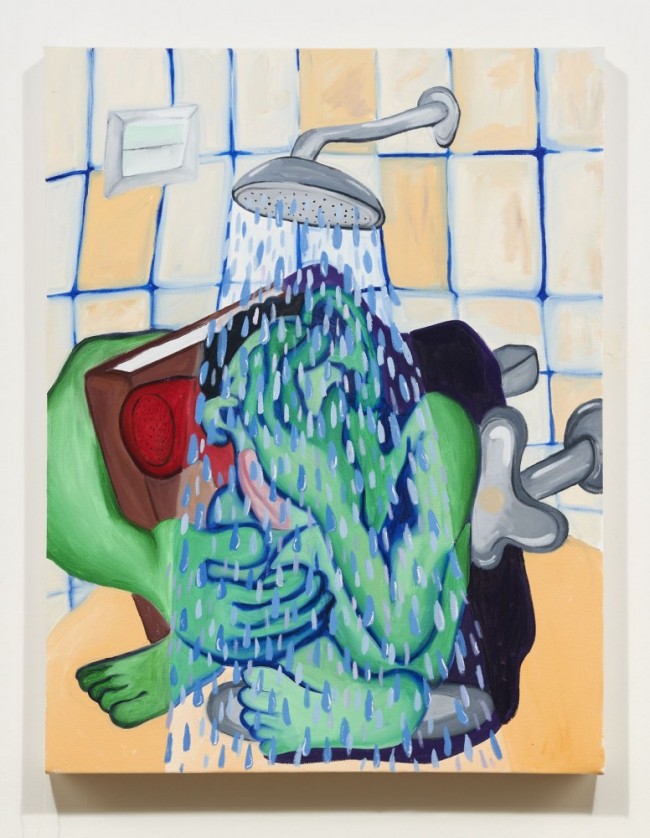

Zizipho Poswa, Ukhula 1 (2018); Glazed stoneware.

-

Zizipho Poswa, Ukhula 2 (2018); Glazed stoneware.

Back then, you weren’t making pieces nearly as big as you’ve been doing this year. You started out making small pinch pots.

Yes, they were very small, like the size of a hand. Then I started going bigger, and I went very big. Of course, the bigger they go, the longer they take. And with the bigger pieces, I had to include other techniques. Sometimes I start by throwing a piece and then coil halfway through until it is done. Other times I use a press-molding technique and finish off with a pinching technique. I love hand-pinching as it is the most direct and traditional method of working with clay. On the latest pieces, the focus is more on the form, texture, and color.

This year you’ve participated in two important gallery shows in South Africa with collectible design gallery Southern Guild: Extra Ordinary and Colour Field. How did this come about?

Before Extra Ordinary, I sat down with Southern Guild Creative Director Julian McGowan to brainstorm. He wanted to extract what he thought was possible, as I had been stuck doing smaller pieces. He started stacking some of my vessels on top of one another and I was instantly drawn to the forms that emerged.

-

Zizipho Poswa, Umthwalo 1 (2018); Walford white clay.

-

Zizipho Poswa, Umthwalo 3 (2018); Walford white clay.

And so the Umthwalo series was born, speaking to your experience as a Xhosa girl, fetching water from the river in a rural Eastern Cape town in South Africa where you spent school holidays.

We’d collect this water by balancing a bucket on our head, a practice called umthwalo. So these totemic ceramic pieces are an ode to the load carried by Xhosa women – both physically and metaphorically. I have fond memories of carrying different types of vessels, and the inkathas we would create to protect the head and support the vessels. The pieces are inspired by these elements: the head, inkatha, and vessel.

It’s an eye-opener to hear you mention that you did this sort of labor yourself. You seem like such a city slicker now.

(Laughs) It was a twice-daily event – all the water needed for your daily washing and cooking. I also used to grind maize – a very hard manual exercise that takes hours – and ukusinda, using cow dung to plaster the floor. It was tough labor but it’s an experience that I wouldn’t change for anything.

Zizipho Poswa, Umthwalo 4 (2018); Walford white clay.

For the Ukukhula series, the two sculptural pieces talk about opposing ideas such as masculine and feminine; traditional heritage and contemporary art; aggression and protection; success and struggles. Tell me about this.

The word Ukukhula means growth in the Xhosa language and references my personal and creative journey as a ceramicist making my foray into collectible design, pushing my medium to a more monumental level and delving deeper into my personal narrative. It’s a distillation of my experience as a Xhosa woman, connected to my traditional heritage while staking my claim as a contemporary artist, and is testament that hard work pays off. These pieces represent the toughest times, where I had to be strong, fight for my dreams and not give up; and my greatest moments, such as my graduation.

Text by Tracy Lynn Chemaly.

Portrait Richard Keppel-Smith.

Photography by Hayden Phipps for Southern Guild unless stated otherwise.