INTERVIEW: Sophia Al-Maria, Self-described Time Traveler with a Starchitect-Centered Screenplay on the Way

It was Sophia Al-Maria who, in the early 2010s, coined the term “Gulf Futurism” to describe a sensibility in the realms of art, architecture, and pop culture that was emerging in the post-oil Persian Gulf in tandem with the region’s urban and economic development. As an artist, filmmaker, and writer, Al-Maria has developed a wide-ranging body of work inspired by both her Qatari-Bedouin roots and her upbringing in suburban Seattle — The Girl Who Fell to Earth (2012) was a 288-page coming-of-age memoir, while Black Friday, her 2016 Whitney Museum solo show, focused on the Gulf’s embrace of the shopping mall. She is currently working on a feature-film screenplay about a fictional British “starchitect” who is planning a monumental urban development in the Gulf, and her first public artwork, a circular platform, is also currently in the works for London’s Serpentine Galleries. Both projects find inspiration in the sun, which also features in Al-Maria’s Beast Type Song (2019), a film whose action is set in the midst of solar wars. They’re a metaphor for imperialism borrowed from Etel Adnan’s 1980 poem The Arab Apocalypse where the sun stands for the eye of colonial power. Longtime confidant and supporter Hans Ulrich Obrist spoke with Al-Maria as they journeyed across the Atlantic Ocean, from the U.S. to the U.K., a pre-pandemic conversation that went from sunset to sunrise, spanning the ride from the airport terminal bus to a plane to a taxi cab hurtling through the streets of London.

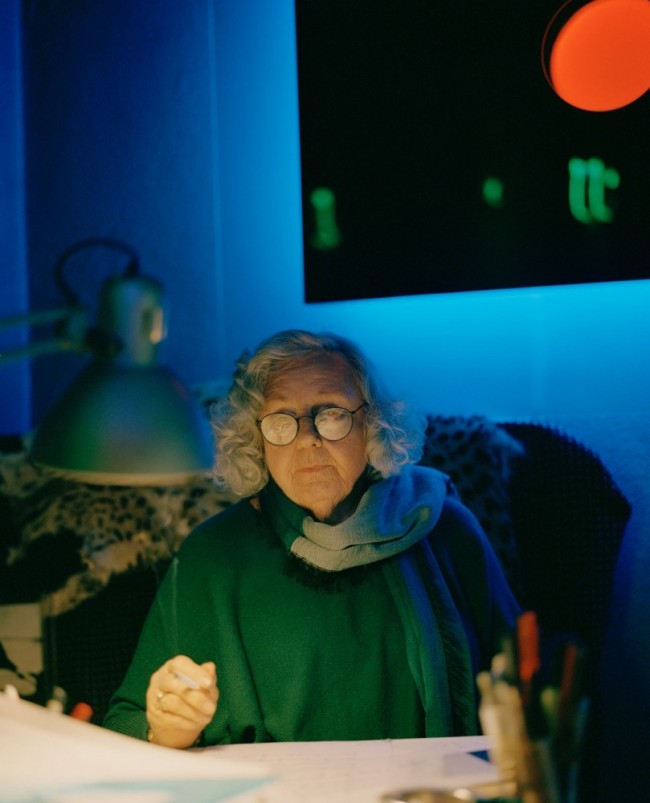

The artist Sophia Al Maria photographed by Mathilde Agius for PIN–UP.

Hans Ulrich Obrist: What can you tell me about your new film?

Sophia Al Maria: It’s my first feature film, which I suppose is my favorite format. I’m still debating the title. What do you prefer? The Marina or The Radiant City?

The Radiant City.

I think I’m stuck on The Marina. But it’s a good title, right?

Yes. It has an urgency to it. You started working on this film a while ago. How has it evolved?

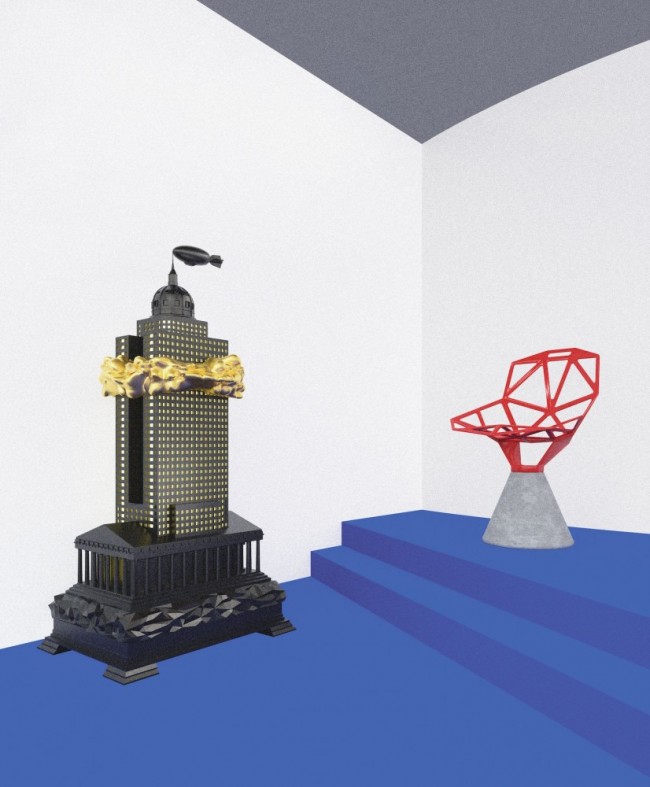

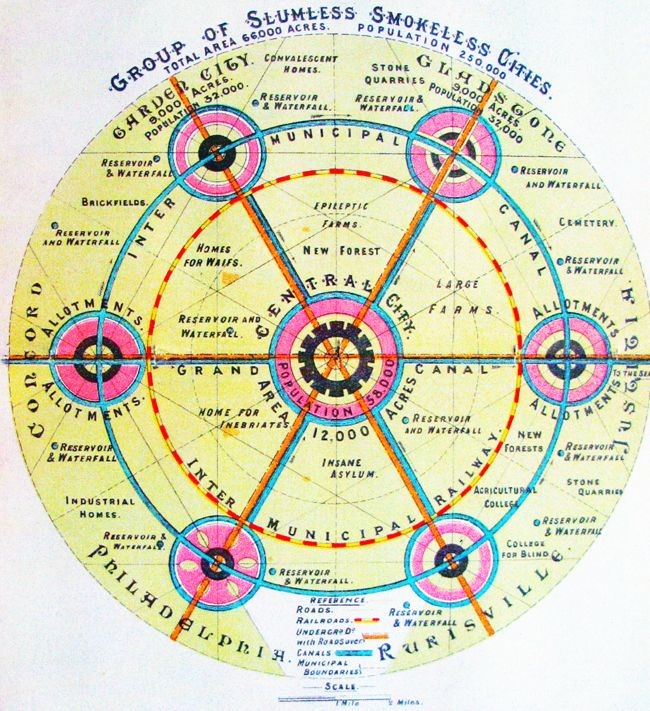

The life of a script begins with a pitch document usually, or some kind of outline. I started working on that three years ago. And now I’ve just written the first draft so it’s deepened considerably. It’s about an architecture project, not unlike some of the mega starchitect projects that you’ve been adjacent to and I’ve worked in and around, for example the museums in Qatar. So, the Marina is a huge Brasília-style project that a chimera Gulf country is building to forge a way towards “sustainable growth” in the region. There’s this British family of architects who win the tender to build it. The mother/master-planner is a Zaha Hadid-type character with twin sons charged with overseeing this fantasy, and thus begins a spiral into The Marina.

Is there a master plan?

Yeah, there’s lots of master planning. I mean, really, the whole project is centered around unpacking Britain’s relationship with the Gulf countries. The parceling out and drawing maps and borders from on high. It also deals with the trickle-down trauma of Gulf countries’ relationship with the labor forces they rely on. It’s investigating all that through the format of a slick thriller.

You said earlier that the feature film is your favorite format. That’s really fascinating.

I’m not sure it’s my favorite as an audience member, but it’s my favorite as a writer. I just think it’s much more fluid, and the possibilities of experimenting with narrative are much more exciting. Television has to have certain muscles to function, plot engines and all that. Things like advertising breaks come into play or how long it takes for someone to fall asleep on Netflix. It’s an interesting moment. I feel like more and more all I want to watch is plotless ambience. Like nature documentaries or screensavers.

You’re very interested in sci-fi. Could this film be classified that way?

I think of it as a solarized noir. In the film it’s always hyper bright, and the horror lies in the fact that there is nowhere to be in the dark. It’s just blinding brightness, and that’s terrifying to me. Glinting glass, overpowering sun, the whir of AC and industry are all recurrent motifs.

I was just reading an article about how all of a sudden in Los Angeles, which has always been the city of the sun, there’s a horror associated with that — there’s no more escape from the sun.

Yeah, it’s the unblinking eye. I love how Etel Adnan writes about the sun in The Arab Apocalypse. I think that the horror of Los Angeles is similar to the terror of the Gulf, in that it should not exist. As a metropolitan city, I mean. Riyadh has two days of water should anything happen. And L.A. is similarly precarious. Actually, Chinatown is definitely a reference for The Marina with the water-rights subplot.

Can you tell me more about the fictitious architecture in The Marina?

Do you know this funny thing that happens in the Gulf? Oftentimes, they don’t temper the glass correctly on those big skyscrapers, so if the air conditioning is very cold inside and it’s very hot outside, the glass explodes. You’ll see all this beautiful glitter all over the ground and missing teeth in buildings’ façades. So, there’s a moment in the film where one of the main characters is standing at the window on the 70th floor and all of a sudden the façade explodes. He’s looking at his own reflection, and then boom!, the whole thing cracks and explodes in front of him, leaving no membrane between him and the environment outside, which is impossibly and dangerously hot. It’s like a homicidal sun. It kills really quickly.

The artist Sophia Al Maria photographed by Mathilde Agius for PIN–UP.

You’ve written an amazing book, The Girl Who Fell to Earth, and you’re writing films and TV series. How did you first come to writing?

There was a period in the late 1990s when my father was in exile. I would help my mother write letters to Amnesty International about our family’s situation.

Was your father’s exile involuntary?

Yes. It was not by any actual action, more by proximity. A lot of people from Al-Ghufran, which is one of the clans inside our larger tribe of Al-Murrah, were exiled. Some people still don’t have their passports, but mainly it’s resolved. But that was when I remember adults being like, “Oh wow, you can write!” But I’m less and less interested in writing narratively, and more and more interested in the way that poetry functions. A poem is like non-didactic philosophy. You feel a poem, and through that understand things which are difficult to comprehend.

So you’re writing poetry?

Yes, I am. I think my poetry is quite cheesy, but I enjoy it.

Your project for the Serpentine also has to do with the sun. And what is interesting is that you’re venturing into public sculpture. We are so focused on exhibitions, but there’s this whole world of public sculpture where we can reach people who never come to an exhibition. The necessity of that became clear to me the other day. A taxi driver dropped me in Kensington Gardens at 7:00 a.m., when I was coming back from a trip. So, he obviously assumed I worked there, because nobody would go to the gallery that early. He said he always wanted to talk to someone who works in the Serpentine to thank us, because, two years ago at the park, his daughter suddenly came across our summer pavilion. She had an epiphany and now wants to become an architect. I said that was amazing, and asked if he had ever been to our gallery. He said no, he had never been to a museum in his life. I asked why. And there was a long silence in the car. It was like a minute or so, but it felt endless. He said, “Because it’s not for people like us, you know?” And so, I think that with public art you can reach people who might never come to a museum.

I am very struck by that story. It also reminds me of when I did a show at the Whitney Museum in 2016. I invited my mother, and I really wanted her to come. I was going to bring her to New York and she says, “Oh honey, I don’t enjoy museums,” or, “Museums aren’t my thing.” I think it’s very daunting for a lot of people to enter that space. It’s intimidating for a variety of reasons. This is my first public-art project, and it’s also the first physical stage I’m building for a performer. I’ve thought a lot about the collaborations I’ve been doing with Victoria Sin and, to an extent, the works with Bai Ling. These collaborations have been very much about stepping back and relinquishing control over what is done with the space, for the stage.

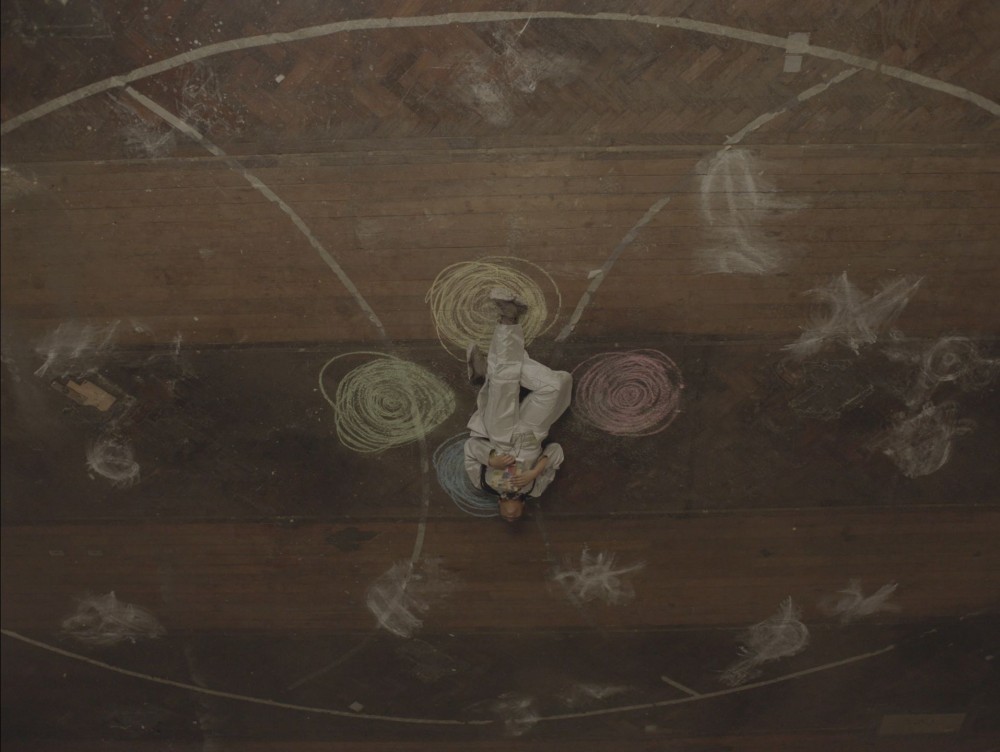

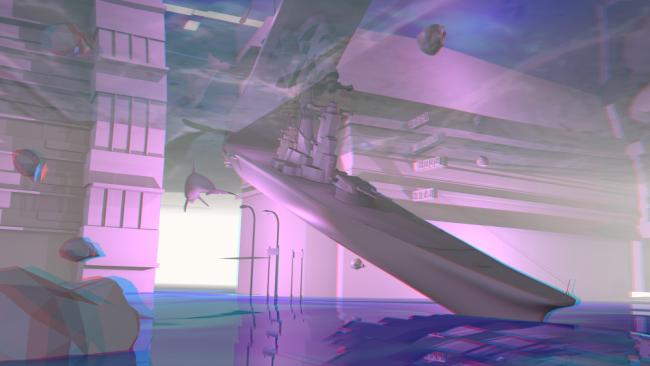

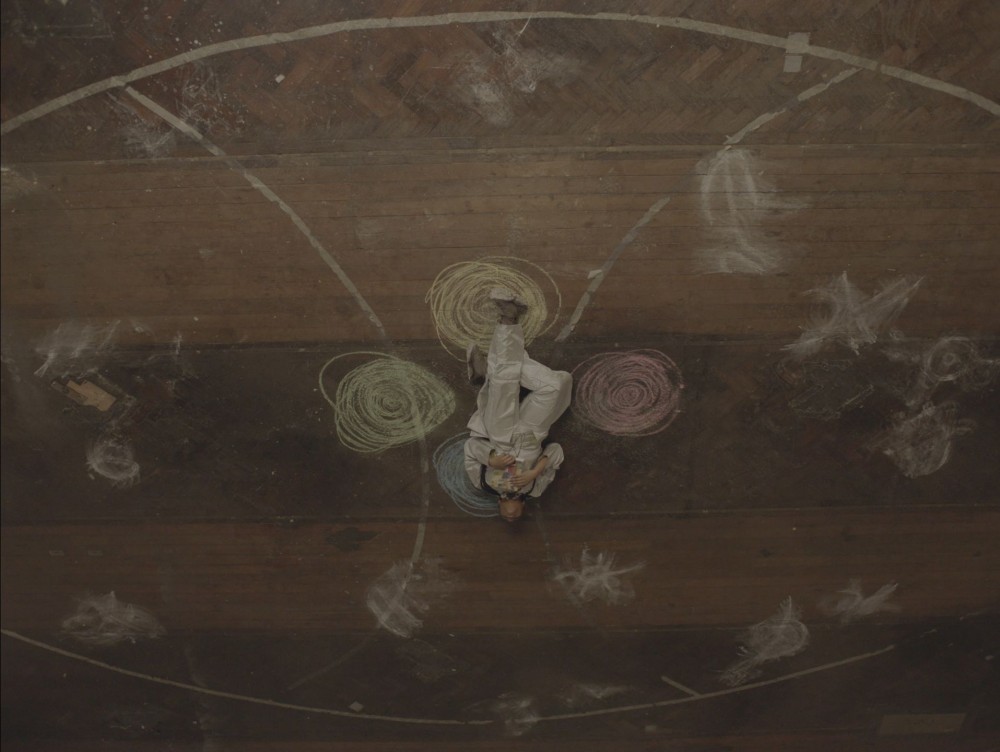

Still from Sophia Al-Maria’s film Beast Type Song (2019). Courtesy of the artist.

Can you talk about your work with Bai Ling?

I think there were four films in total. There was Mirror Cookie (2018), which was almost a shrine to Bai Ling. Basically, it was a link to self-help practice. And then there was another thing called Major Motions (2018), which was an identity for a production company that doesn’t exist, in which Bai’s holding up a torch of self love, which is a Hitachi Magic Wand.

Why did you decide to collaborate with Bai Ling?

I’ve been fascinated with her since the early 2000s, when she started a blog. She would write these things called cookies, which were meant to be like fortunes from a fortune cookie. But they were often weirdly philosophical, poetic, and profound. I think she’s an incredible, strange, and wise person.

And then more recently you’ve been working with Victoria Sin. How did that collaboration begin?

The collaboration with Victoria has been really transformative for me. I’ve been a fan of their work and they invited me to a Dhalgren reading group, where we were attempting to read Samuel R. Delany’s Dhalgren book (an 800-page 1974 science-fiction novel), which is a monumental task that remains unfinished. Victoria and I share a mutual love of science fiction and of Sailor Moon, as well as a commitment to imagining.

Who are the favorite sci-fi writers you share?

We really connected over Octavia Butler. That happens a lot these days. We spoke about her Xenogenesis Trilogy (Lilith’s Brood, 1987–89) and alien sex, as well as hyper-empathy syndrome in Parable of the Sower (1993). I could spend so much time with Octavia’s work because I feel that in one chapter there are so many ideas. Even though it’s very simply written, there’s more in one chapter of one of her books than in all of the “traditional” white-dude-bro canon.

So, performance is a big part of your work, and now that’s led you to the Serpentine stage. The beauty of this project is that the stage is going to pop up and then disappear — it’s visible, then invisible.

I think we’ve had an interesting set of problems to play with in the park because we can’t do many things. So I’ve been thinking a lot about playgrounds and what is and isn’t “safe,” and what is and isn’t accessible. The idea is to create a space for wordless communication. It’s a sort of foil to Speakers’ Corner, which is right nearby. So, this piece is for saying the unsayable. Wordlessly. So, that’s why there’ll be an inaugural performance by boychild. One of the things that is so very special to me about boychild’s work is the way in which it pushes away from taught ways of communicating, like language. And I really feel a spooky understanding when I witness one of her performances. It feels like a mighty gesture to be able to communicate that way. And I would like to encourage the public to do so. To break that boundary. To be a body, not just a spout of words. Myself included.

So, by having boychild do that inaugural ritual, it’s an invitation to everyone?

Exactly. boychild is the sower. The event will be a seeding.

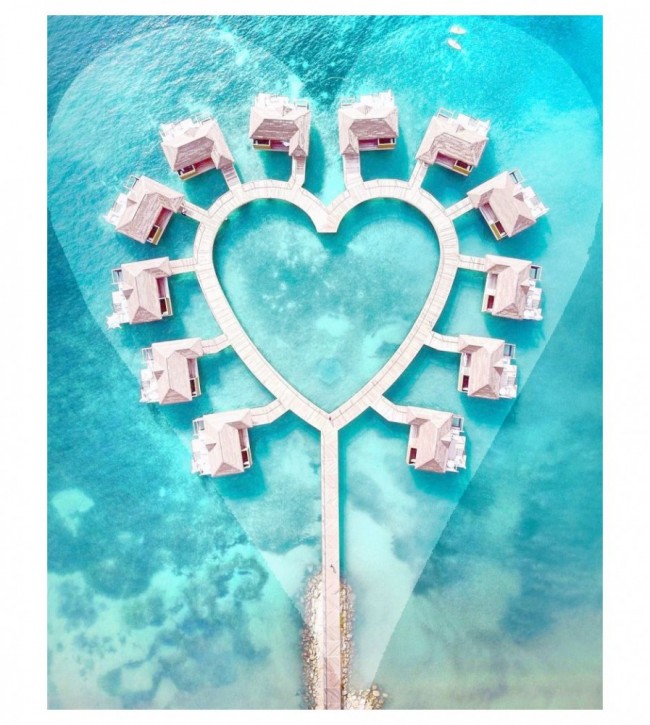

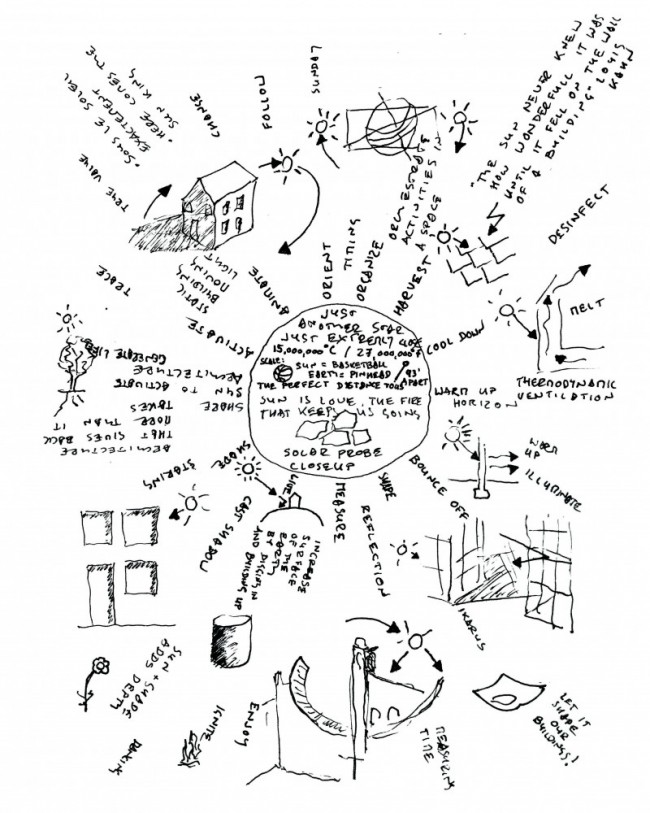

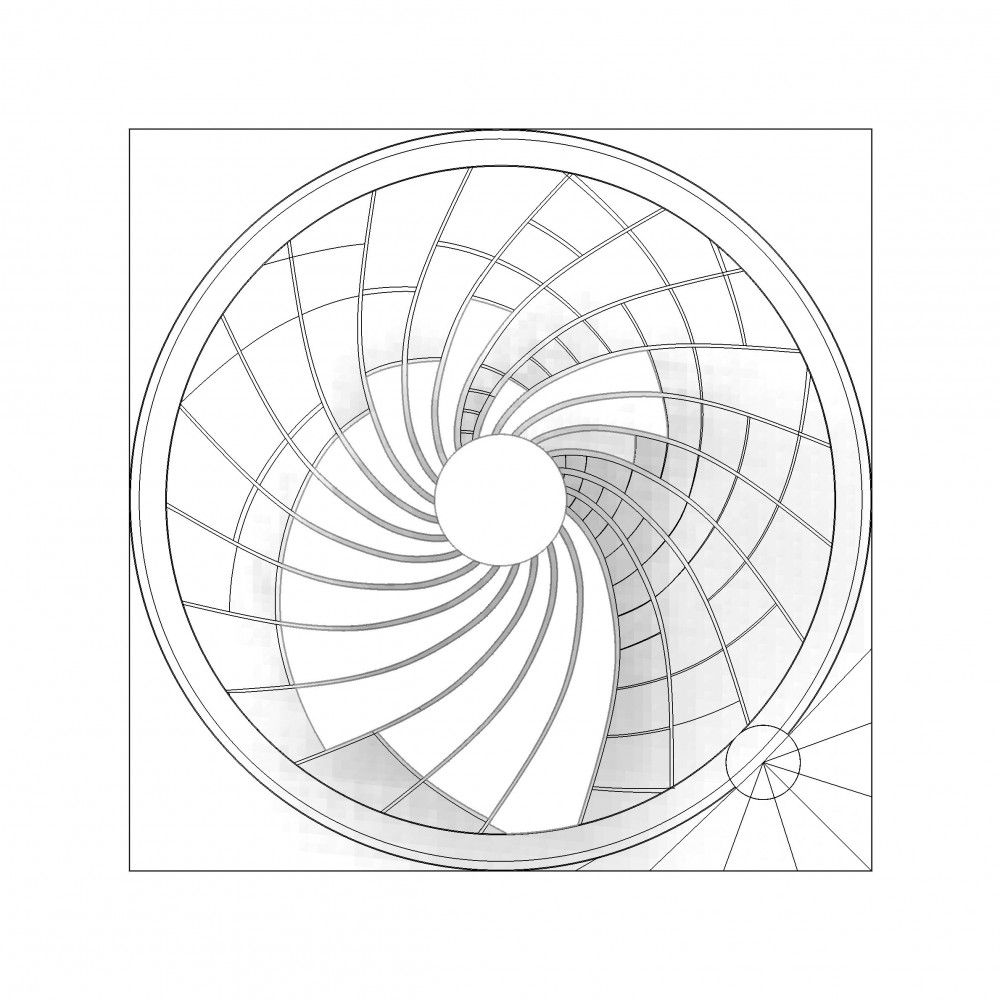

There’s also a pattern which will be on the stage?

Yeah, a pattern similar to a sundial. And also like a dandelion. You know, when dandelions seed, it’s also called a clock. The stage is in many ways like a clock, a sundial, or a dandelion made of metal. A lovely chromed asterisk. The asterisk has become a real theme in my work for everything that is inexpressible.

A working drawing of Sophia Al-Maria’s first public artwork Tarraxos (2020), an ongoing project with Serpentine Galleries, designed for Kensington Gardens in Central London. Al-Maria has conceived of the sculpture as a platform for park goers to engage in deep listening and meditation. This illustration shows the sculpture from a birds-eye-view, its spiral pattern inspired by sundials, dandelions, and asterisks. Concept drawing by Rhi Jean.

Is the asterisk a new thing?

Asterisks have been present in my work as a screenwriter for a long time, because that’s what happens when there are revisions on a screenplay. But asterisks have become really important for me because they’re incredibly dense, symbolically. They’re very, very old, and they have many different meanings, or I suppose origins, from Babylonia and Sumer. And the thing that they’ve come to represent for me is almost everything that cannot be expressed. Similar to an expletive, when you black out the “u” and the “c” in f**k.

Is silence an asterisk?

Yes. I often draw pictures of this face with an asterisk over her mouth, as if it’s been sewn shut.

And so the asterisks migrated from the screenplay into the visual artwork. Your practice is almost super string-theory quantum physics. Because you have all these parallel realities in your work — installation, video, film, poetry, sculpture, photography, novels, TV series. It’s a sort of Renaissance practice that includes all disciplines and art forms. And you seem to disappear for three or four months when you’re working on one. Is time an important aspect to working on screenplays?

Yes. One of the reasons I think I have to disappear is because I’m time traveling. I write mostly historical fiction, which requires a lot of research. I like to go quite deep into the time period. I’m really fascinated by the French Revolution, for example. I was working on this TV show about Madame Tussaud, which never was made. She was stationed next to the guillotine, and tasked with making death masks of all the aristocrats who were killed. They had multiple copies of the heads that could be paraded around different areas of the city, so that everyone would know: this person is dead, that person is dead. But I dove deep into it for a good five months.

David Lynch told me that sometimes, when you work in television or in the movie industry, there can be a situation where you no longer identify with what you’re working on.

Exactly. The more money there is, the less power you have. Actually, in the book you gave to me to read on the plane, there was a quote by the author bell hooks. It was about how when your power is recognized, some people will want to destroy it or take it away from you. That was essentially what happened to me with the last project, and it was a very upsetting situation.

The artist Sophia Al Maria photographed by Mathilde Agius for PIN–UP.

Do you have any utopian projects or dreams?

In my lifetime, I hope that utopian communities are possible and that there’s an aftermath of this particular reality that we’re living in. I think a lot about having some dogs, some goats, some honey-bees, and some trees I can tend.

Has the sun played a role previously in your work?

There are a few moments in my film Beast Type Song (2019) where there’s a reference to a solar war happening somewhere up in the sky. Elizabeth Peace, Yumna Marwan, and boychild all play veterans of this war. The film draws on the idea of a solar war from The Arab Apocalypse. In it, Adnan uses the solar war as a metaphor for colonial expansion and imperialism — the sun being the eye of the colonial power. I reread this poem every time I start something new.

Still from Sophia Al-Maria’s film Beast Type Song (2019). Courtesy of the artist.

We are both obsessed with and always nurtured by Etel Adnan.

Yes. With such simplicity and grace, Etel makes me feel all these things, from rage to relief, and I am amazed by her. I’m also amazed at all of the people that worked with me on that film Beast Type Song. I had the help and generosity of many collaborators who are also filmmakers and artists who brought such power to the piece by their presence. Farida Khelfa reads from an essay about the Battle of Algiers. Wu Tsang reads a sonnet by Shakespeare. There are voice notes from my mother and also from Elizabeth Peace’s mother. There are so many other things that didn’t make it in. Laura Cugusi reading Pasolini’s A Desperate Vitality, for example. So, it was like a big collaborative bag that we just threw everything into. I’m very happy with it. It opened new territory for me, and yet I feel utterly unterritorial about it.

I’ve watched it 25 times. It’s very exciting. And you mention your mother, which brings me to the very last question I wanted to ask you. What’s the first word you spoke as a child?

Picture.

Extraordinary! How did that happen?

My mother said that when I was very small, like a baby baby, she used to point at different things around the house and say what they were. So, one day, I looked up at this Palestinian solidarity poster on the wall and said, “Picture!” I suppose it’s only appropriate that I work in pictures now.

Text by Hans Ulrich Obrist.

Portraits by Mathilde Agius.

Originally published in from PIN-UP 28, Spring Summer 2020.