INTERVIEW: Shumon Basar Talks “Age Of You” Exhibition And The Extreme Self

In the wake of rapid technological change, the concept of the self as we know it has been radically destabilized. This recent development is the subject of Age of You at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Toronto, a timely and prophetic exhibition organized by novelist Douglas Coupland, super-curator Hans Ulrich Obrist, and philosophical mastermind Shumon Basar. The curators mark Cambridge Analytica’s successful Brexit and Trump campaigns, both in 2016, as the historical turning point, which upended traditional ideas of individuality and selfhood and exposed previously unimagined applications of personal data, today arguably the hottest commodity around. Bringing together the work of over 70 contributing artists from an array of disciplines, the immersive show is a sleek, smart, and vaguely depressing attempt to come to terms with how individuality has been hijacked and sucked into an uncharted netherworld, both cute and sinister. PIN–UP spoke with Basar about this perplexing new reality and what the curators call “the extreme self.”

-

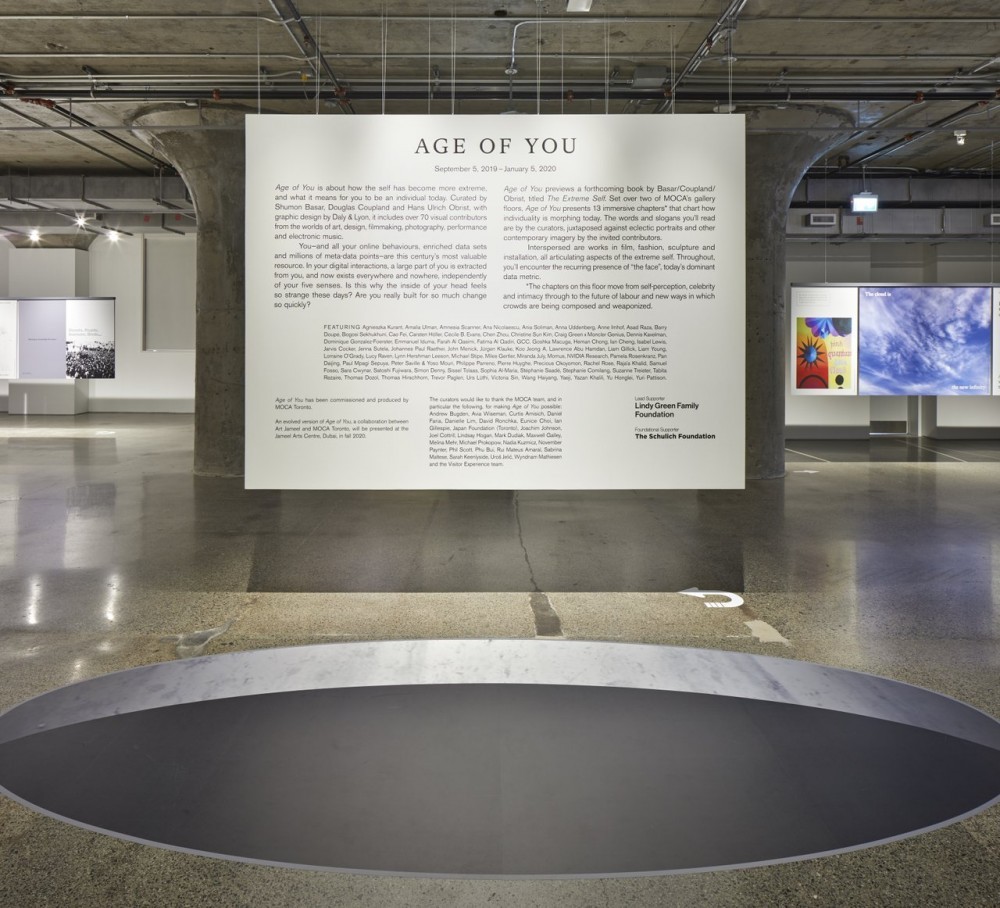

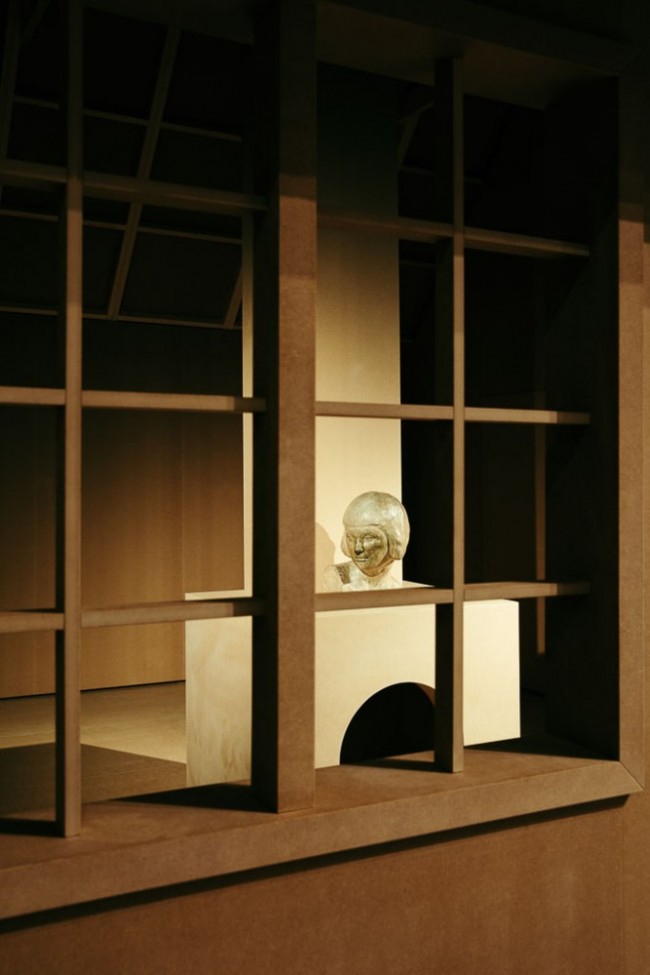

Installation view, Age of You, MOCA Toronto. Photo by Tom Arban Photography Inc.

-

Installation view: Satoshi Fujiwara, Crowd Landscape, 2019; Age of You, MOCA Toronto. Photo by Tom Arban Photography Inc.

What is so extreme about the self today?

Everything! The political discourse has taken a rather hysterical turn. It’s hysterical on the left, hysterical on the right. You have no real voice today, which is all a consequence of this seismic event that was 2016. Another way of describing this project is it’s a short history of what's happened to the individual over the last five years.

Age of You continues a conversation from a book you published together with Coupland and Obrist, The Age of Earthquakes.

With Age of You the viewfinder has moved. While the 20th century was fueled by fossil capitalism, the 21st century is fueled by data capitalism. So instead of oil and gas, every single one of us has become a resource that can and will be extracted for maximum profit. That means in a sense, that every single one of us is at the center of this new world, new reality, and new economy. But because change happens so quickly and the changes happening are so profound, we’re going through what I call “change vertigo.” I don't know about you, but I wake up every morning to something entirely new.

I call this the vertigo of reality.

Exactly. What you took for granted yesterday, you can't anymore. The knowledge that you’ve built up proves useless to handle reality because the conditions are constantly changing. This accelerated change introduces the vertigo feeling and you're just trying to find a way to cope. If you have the luxury, you might be able to try and understand, but I think most people are just trying to cope.

Hyperconnectivity gives us a fake sense of safety when in fact it’s not in our interest.

Quite the opposite, right? There was a turning point in 2016 when taking a picture of yourself with your best friend suddenly was not innocent anymore. Nor is filling in one of the google captcha puzzles: how many streetlamps do you see in this picture? Nor is the voluntary offering of information in personality tests that we gave purely because we thought it was just a fun social transaction. This data has now been weaponized. That’s what I mean when I talk about innocence lost. Having said that, it's not like everyone's left Instagram or Facebook. So we've lost our innocence, but we’re still participating in this website and in these instances of weaponization. That's because ultimately we can’t live without these platforms anymore.

-

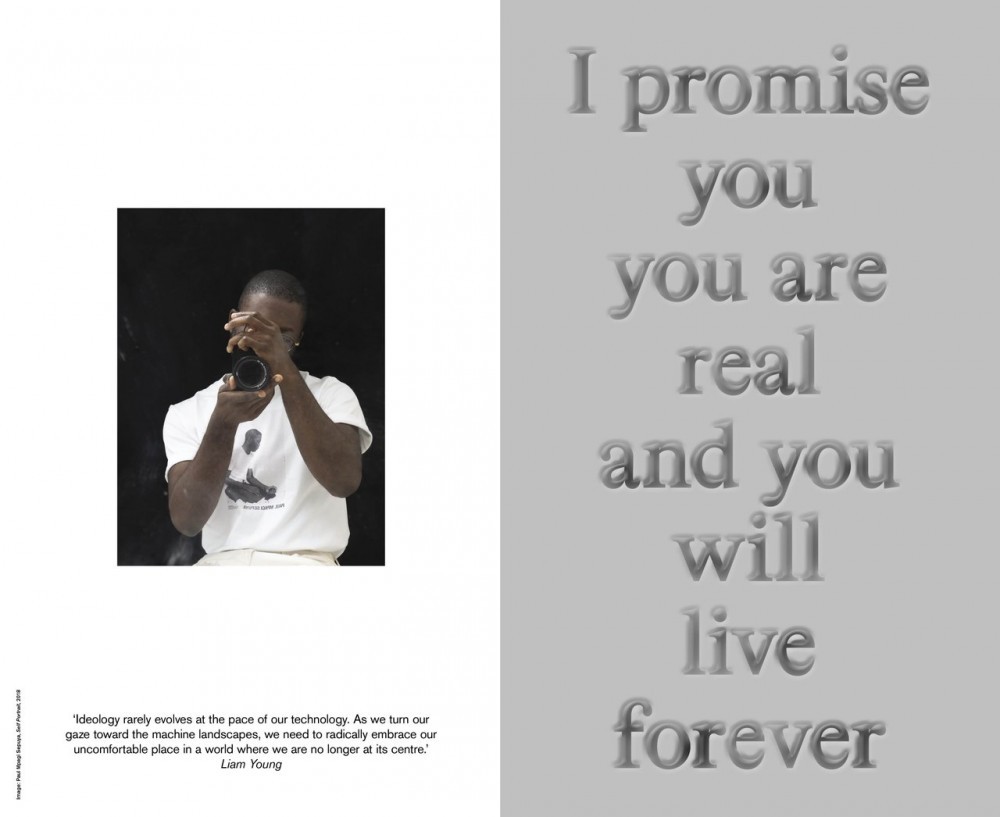

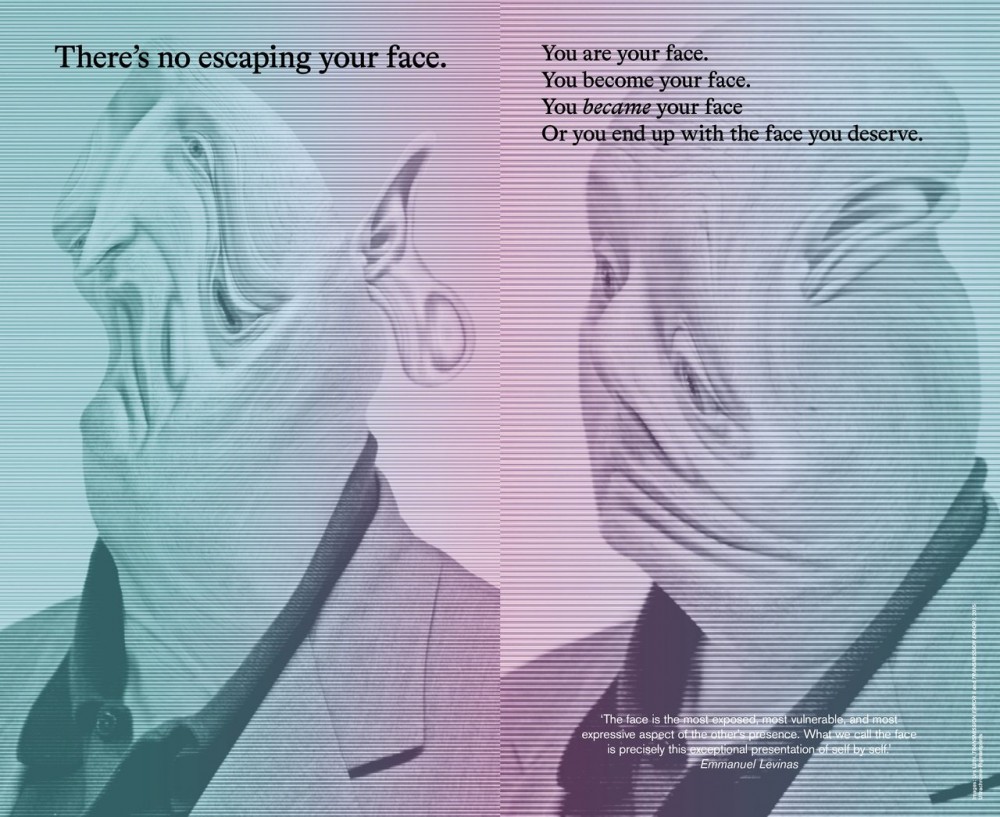

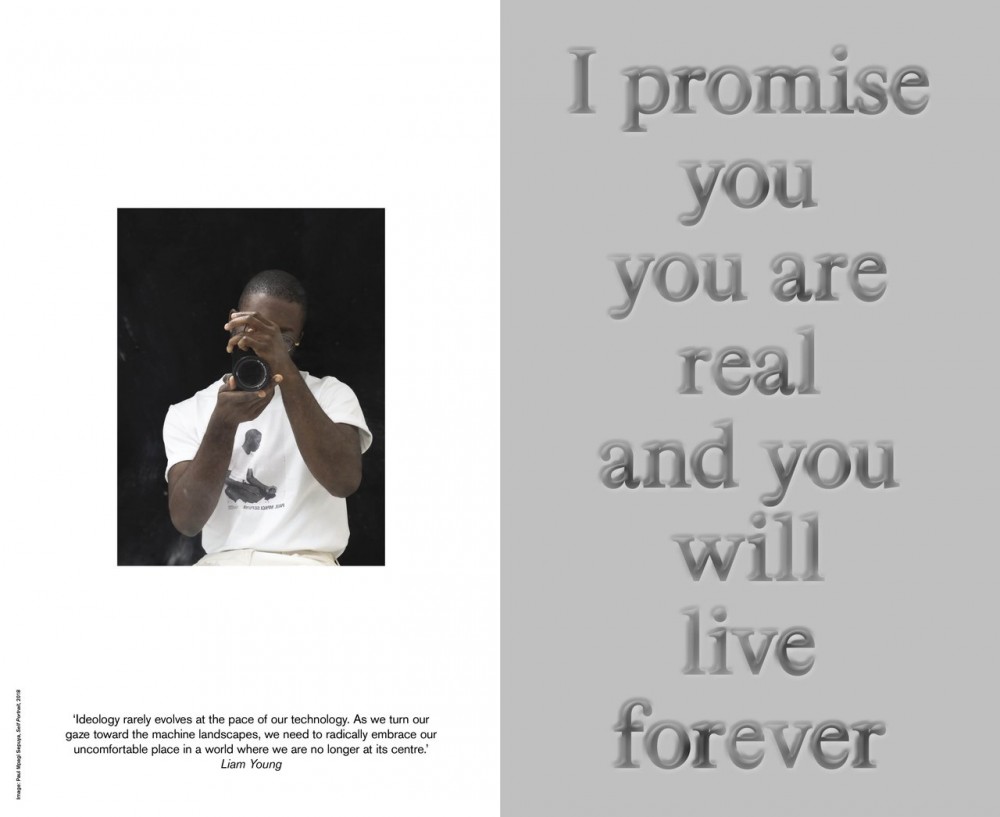

Words: Shumon Basar/Douglas Coupland/Hans Ulrich Obrist; Image: Paul Mpagi Sepuya, Self Portrait (2018).

-

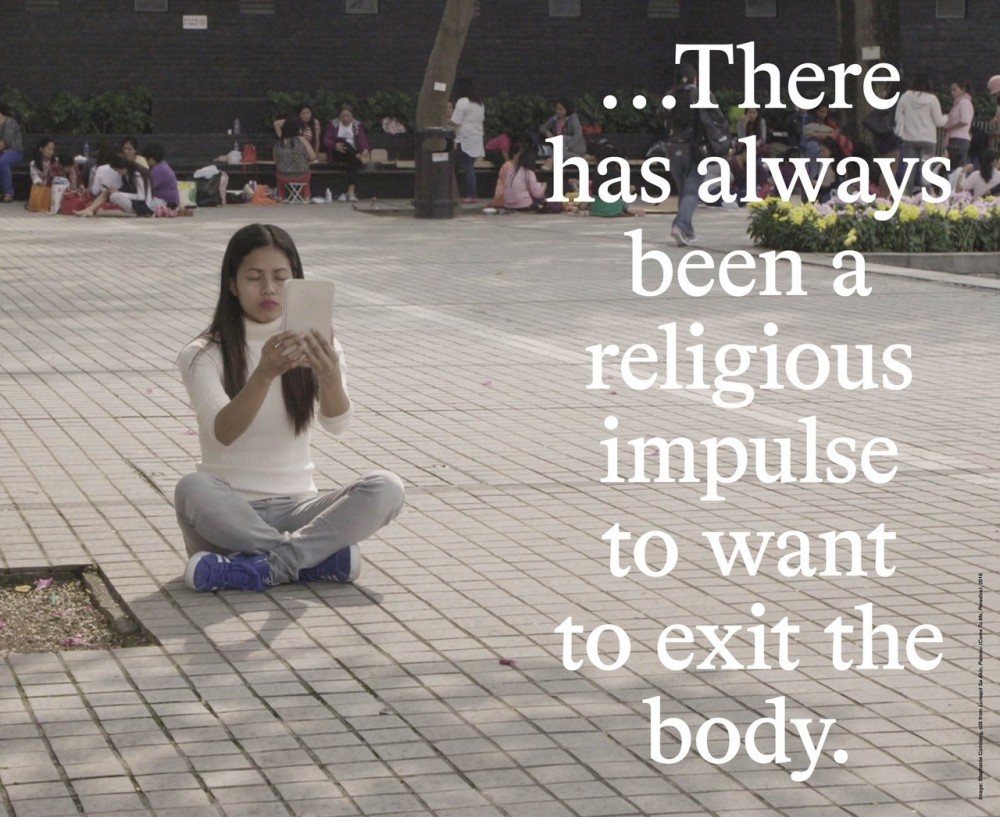

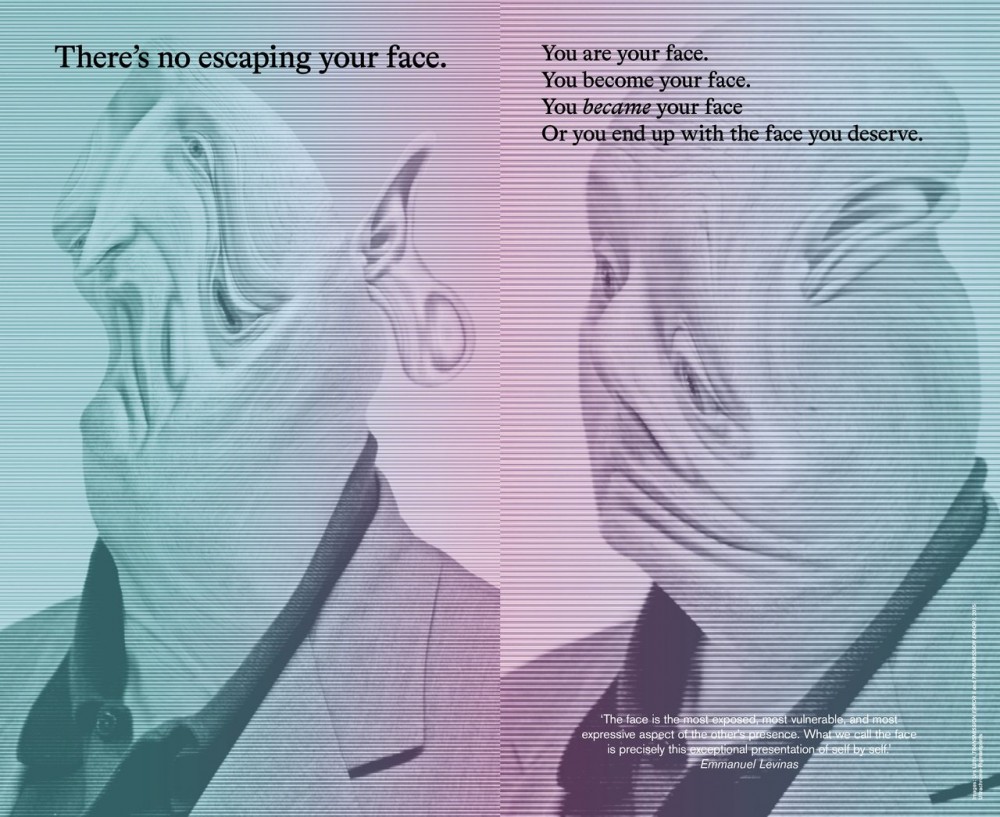

Words: Shumon Basar/Douglas Coupland/Hans Ulrich Obrist; Image: Stephanie Comilang, Still from Lumapit Sa Akin, Paraiso (Come To Me, Paradise) (2016).

-

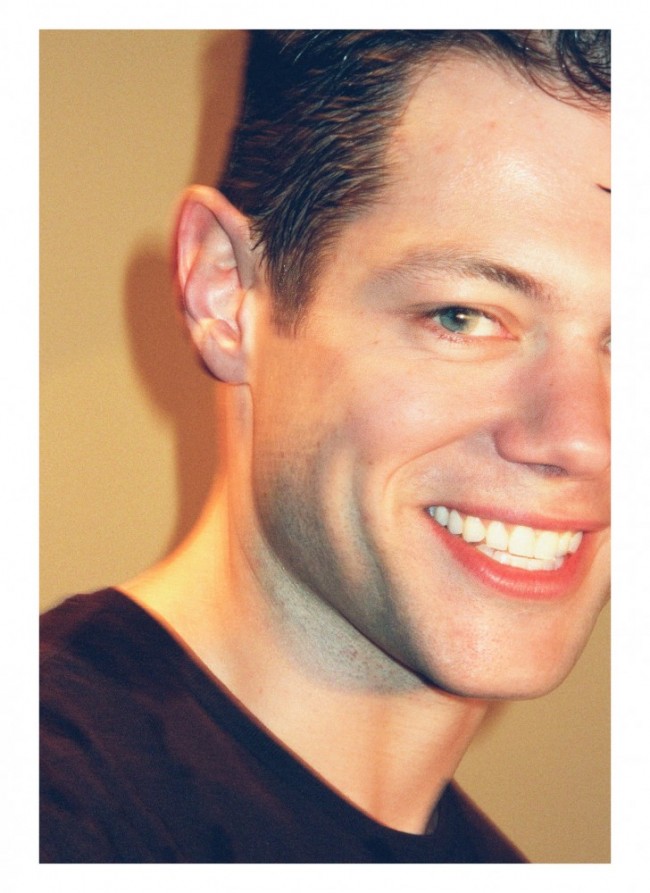

Words: Shumon Basar/Douglas Coupland/Hans Ulrich Obrist; Images: Urs Lüthi, TRANSMISSION ERROR II and TRANSMISSION ERROR I (both 2015): Ultrachrome-pigmentprints.

You’re talking about 2016 as a kind of ground zero for this experience as in the Trump presidency and Brexit?

Since 2016 any innocent relationship that we may have had to the data that we produced has been obliterated and that data has now become the most valuable resource in the world. That innocence is completely shattered. We now inhabit a new space of knowledge — although I still think it's mostly ignorance — and we’re beginning to feel the effects of these transformations in every part of our lives. So whether it's in our interpersonal relationship with the person that we love, or right up to economic implications and the health of democracy itself, we're all feeling it. But we don't necessarily have the language or the words to describe what these things are and what they're doing to us. And that has always been the nature of our projects together: to try and give names and words to a set of shared feelings that we all have, but haven't been able to articulate yet.

That process you describe was incited by Cambridge Analytica and is very well described in Johane Noujaim and Karim Amer’s documentary The Great Hack.

They've done really important work. When those events happened, we thought this was just a kind of glitch in the algorithm of history. We agreed that this was just the end of the hegemony of well-educated liberals. But now we realize that it was completely engineered. There was nothing accidental about it and there was nothing providential about it. It was engineering. And I think engineering is a really important word because a vast percentage of our emotions that we think we are having in an authentic way are actually emotions that have been engineered by someone or something else.

A thought that’s quite depressing.

There's a line in The Age of Earthquakes where we said, you know coincidences like this are like a glitch in luck. But now we know it's an algorithm doing its job. It’s a paradox of scientific observation. An experiment is only as good as the authenticity of the observer, right? And so if we are trying to observe ourselves, how could we? We would have to be sure that we're observing ourselves in an authentic way if our emotions and our optical faculties have been externally engineered. That's the kind of inflection moment that we find ourselves in now. Like, do I really like those shoes because I really like those shoes and I've always liked shoes like that? Or is it the consequence of two years of subconscious signaling in my feet? We also talk about the tyranny of the minority. And this is where democracy is now. It's no longer about trying to win the hearts and minds of the base. It's pinpointing those probably just thousands of decidibles, as they are described by Cambridge Analytica, who are ultimately going to change the face of an election.

And even though a growing demographic knows this, the media today discusses the Democratic Debate as if it matters while it's completely futile.

It's often a lot easier to keep doing things the way that’s familiar. There’s probably trauma psychology involved. One way to deal with trauma is simply to pretend like nothing's happened, keep repeating how you've always done things, and maybe you can delude yourself that nothing has changed. Up until that moment in 2016, reality just kept following the same rules and then suddenly seemingly out of nowhere the fabric of reality turned inside out. When we were invited to do this project in Toronto, it was early-mid 2017. I was still in a kind of hangover, thinking, “Oh, that just happened, right?”

Can you talk about where the book The Age of Earthquakes and the exhibition Age of You intersect?

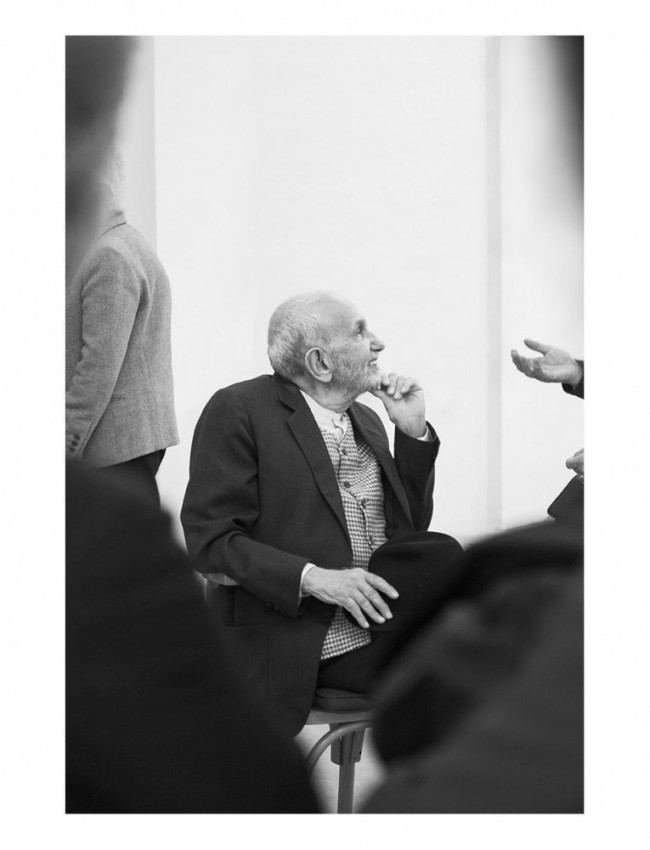

The Age of Earthquakes was an homage and an update of Marshall McLuhan's The Medium is the Massage. This time our spirit guide is a book called The Age of Extremes from 1994 by Eric Hobsbawm, the great Marxist historian. The English subtitle is really beautiful: A History of the Short 20th Century. Hobsbawm’s 20th century starts off with the infamous gunshot in Sarajevo in 1914 and ends with the collapse of the Soviet Empire in 1991. For him, the 20th century happened exactly between 1914 and 1991. By chance the three of us discovered that it's a book that holds shared importance for all of us. Doug (Coupland) was once asked in an interview a few years ago if there was any book that he’d read that he wished he could have written himself. He answered immediately, Eric Hobsbawm’s The Age of Extremes. Hans Ulrich (Obrist) was very close to Eric and had interviewed him many times, and actually the Memory Marathon (a two-day event at the Serpentine Gallery Pavilion) in 2011 was devised with Eric, but sadly, he passed away shortly before. So he's been a really important figure for us. Now we have the Age of You exhibition and there will be a book called The Extreme Self. We've taken Eric’s chapters and updated his concerns about the 20th century to the 21st century. That's how we got the skeletal structure. Chapter one is about what is the extreme self, chapter two is about we call fame and the face, and then chapter three is called the intimacy industrial complex, which is the technology-ization of intimacy.

Sex.

Right. Do people even date anymore? Have sex? You don't know if you're with three people or five or none. Someone breaks it off, and the other person doesn't know that they were ever together. So this zone of total ambiguity is examined. Then as you move through the show, the subjects move from the psychological and the emotional to the social and the spiritual, because then this is the chapter about post-work, all the impending threats from automation, etc. And then one of the big questions running through the show is, what matters more, the individual or the crowd? It's actually a question we asked in The Age of Earthquakes, but we realized it's still relevant. The point today would be that the individual is replaced by something else other than the crowds. We wonder what matters more, the individual unit or this multitude?

-

Installation view: Victoria Sin, Illocutionary Utterances (2018); Age of You, MOCA Toronto. Photo by Tom Arban Photography Inc.

-

Installation view: Victoria Sin, Tell me everything you saw, and what you think it means (2018); Age of You, MOCA Toronto. Photo by Tom Arban Photography Inc.

What exactly is a crowd? Is it just like a cloud of data? It's definitely not people gathering.

Imagine 2,378 people all wearing Oculus Rifts at a convention center in Adelaide. Each one inhabits a different virtual reality. What kind of crowd is this? In the past, the crowd had very much to do with the collection of physical bodies in a physical space. We realized through Eric's history of the 20th century that the 20th century was ultimately an ideological battle between the fetishization of the individual and the fetishization of the crowd or mass. I think that’s still the case today, but those two subjects individual and crowd have been replaced, but we don't yet know by what exactly. But we know what happens when we crowd-source and crowd-fund, and apply crowd-logic to these seemingly benign forums of democratic empowerment.

Connecting and community do feel empowering, though.

If I sit in a room in Harare in a village and I'm the only gay person that I know, I can go online and meet an unlimited number of other gay people. Does that mean that I'm part of the crowd? I couldn't be otherwise, without the technology. Otherwise I'd have to do that thing, where I pack a plastic bag, leave my village, and go to the big city. It's easy to always focus on negatives when there are undoubtedly positive scenarios. Technology is great for overcoming alienation because of where you physically are. It's an amazing thing to be able to find connection! But there's obviously a flip side to that, which means a million incels can get together, create a whole movement, which will then bleed into the real world, and end up killing 28 innocent people.

You titled the show Age of You rather than Age of I. Was this a choice you made consciously to reflect that these days the self could only be perceived as mediated and therefore the second-person “you” acts as a lens or a mirror?

That's a really lovely question because I think it goes back to the voice that we tend to adopt in these projects — it's a form of direct address. You could also say therapy speak, self-empowerment speak. Like a Nike slogan: Just do it!

The imperative of acting and feeling or perhaps being?

Absolutely. In the show, the voice slides into different characters. One time it’s the voice of culture, then it shifts to the “I,” then it’s Hans Ulrich (Obrist), then it might be all three of us or none of us. The experience should feel like a conversation, which is different from reading prose. There is a kind of mirror element here, but it's not necessarily showing you what you look like. It's trying to show you the kind of underlying structures and systems of what is making you feel the way you feel right now. It looks like a mirror, but maybe it's more like an X-ray.

It’s as if we have entered a perpetual mirror stage. I think for some people this hall of mirrors might actually feel liberating if you’re trying not to be pessimistic.

I’ve always wondered what McLuhan would make of this if he were alive. But now I find myself wondering, “What the hell would Freud have made of this!?” One thing that technology does is basically dispense of the need for a superego. I mean both as individuals but also as a society, as a culture. What are the basic elements of the social contract that stops us from barbarism? From yelling at each other? Actions have consequences. There are certain inalienable common moral beliefs and values, like the right to life, the right to personal space. Now it feels like what we assumed were absolute ground certainties, these do not apply for the digital or online world.

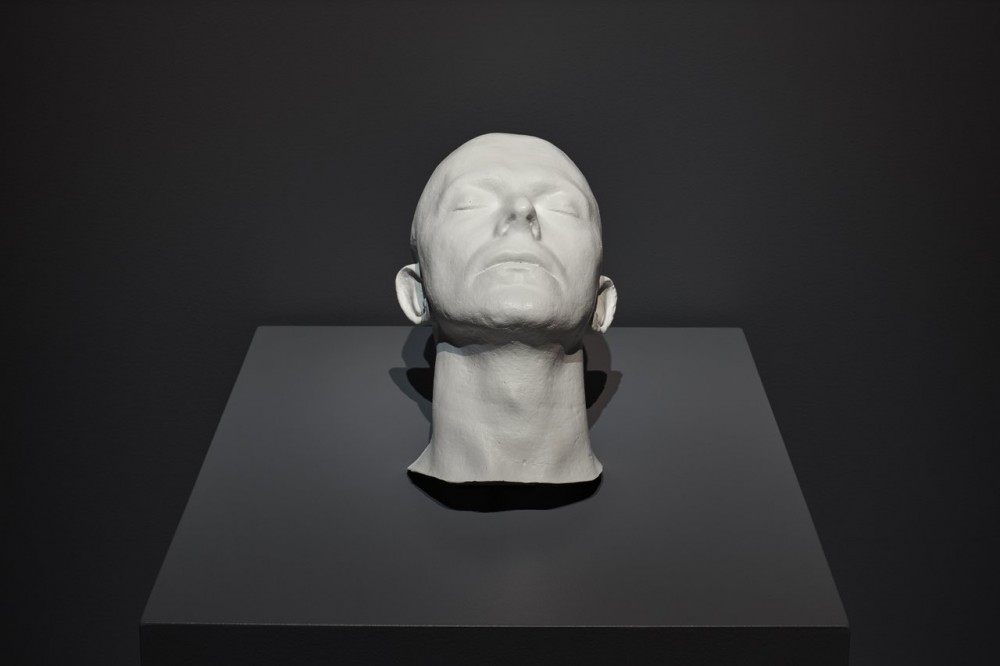

Trevor Paglen, "Weil" (Even the Dead Are Not Safe) Eigenface (2017). Courtesy the artist and Metro Pictures, New York.

This idea of a collective consciousness has been prophetically illustrated in the mass displays of North Korea, where every person basically becomes an analog pixel.

This is one of the places I've always been fascinated by with regards to crowds and individuals and the expectation and the capacity for the populous to cry on demand. Remember when Kim Jong Il died and there was this huge procession? This 70s stretch limo with a huge picture of him on top driving slowly through snowy Pyongyang. It was like a Pope’s funeral. And then obviously every single citizen of North Korea was in tears. It was amazing to watch the close-ups because they were really sad. It’s not that it wasn't real, just over-the-top and hysterical.

Westerners like to belittle North Koreans, claiming they have been brainwashed. That’s a rather hypocritical position taken by the very same people who have subjugated themselves voluntarily yet often unknowingly to the machinery of big tech companies such as Facebook.

Or kind of knowingly. What I find particularly feeble is when people choose to protest about the platform on the very platform. They’ll post some lacerating, incriminating new study about Facebook and post it on Facebook. Or one person posts about thinking of leaving every day for three years, and then they might leave for a month and then they're back.

Are you still active on these platforms?

Yes, in different intensities. I'm a very recent participant of Instagram, which I rejected for a very long time because I thought it was just selfies of 25-year-old girls with amazing abs. And then I was like, I'm always all about new testing grounds and it sort of works at a new speed, so I was curious. In the last year and a half I’ve been discovering memes. I like the existentially nihilistic language of memes. Honestly, they’re some of the few things that get me through every day.

What kinds do you fancy?

I think the best memes are by Gen Y or Gen Z women and girls. I don't know what wave of feminism this is, but it's fucking amazing. It’s going to stop patriarchy. They’re turning gender, sexuality, power, and they spin it in the air like a Russian gymnast at a million miles an hour. First you're like, ”Oh my God, this is hate speech.” But then you realize, their twisted thinking is fantastic. Instagram is the best place to find these memes. So that dragged me in. And now I'm there. I can't get off. Now and then I check into Facebook. I probably use Twitter the least because that’s where the media class hangs out. It turns me off because it just glorifies the media industry and inflates their sense of importance. It’s also the worst culprit in terms of lazy callout bullshit.

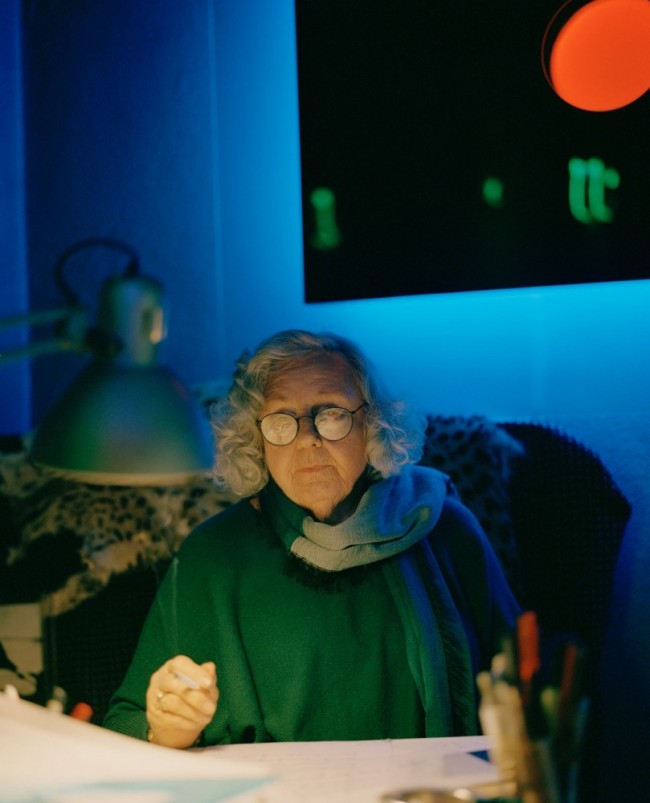

There's a lot of women in Age of You. Is that because they are socially conditioned to vanity and self-reflection?

We just think they're making some of the best work today. It really comes down to that. But we were also interested in the perceptions of femalehood that some of the artists were dealing with. It's an important part of the show and it just happened to be some of the best work that we knew about today. We wanted to make sure that the artists are coming from very different parts of the world. Because again, it's an incredibly active time for women and we wanted to make sure we’re not just hearing elite Western feminists, but diverse voices and positions.

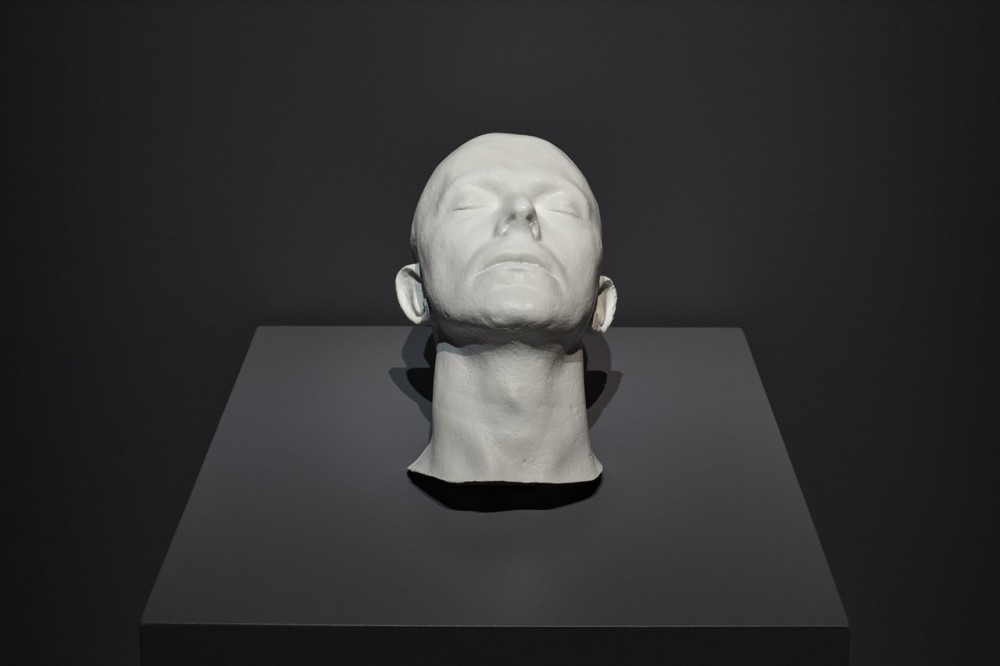

The Impossibility of David Bowie being Dead in the Minds of the Living; Age of You, MOCA Toronto. Photo by Tom Arban Photography Inc.

One of the interesting aspects of the show is that the lines of authorship are blurred. You can see that in the uncredited David Bowie mask which someone bought on eBay.

That's really a very important rubric of the whole project. One of the questions that we get asked so many times and it bores me to death is: which part of the show was done by who? Which part of the book was written by whom? My eyes just roll all the way to the back of my head. It's clear that journalists who ask that missed the point completely. There is not one author behind the Internet The way in which we set up these projects was to proliferate authorship and even complicate it, turn it into this rhizomatic thing. I mean it starts with the three of us (Coupland, Obrist, and I), but then Daly & Lyon the graphic designers are totally instrumental. We have 70 mainly visual artists — musicians, fashion designers, and technologists — and we’ve included comments from Instagram throughout as another layer. It's less that we write this book or we curate this show, it's more like we aggregate them. I think if any of us wants to know about the state of political discourse you just have to scroll down to the 16th comment in any comment thread of any news story. That's basically where politics is happening today.