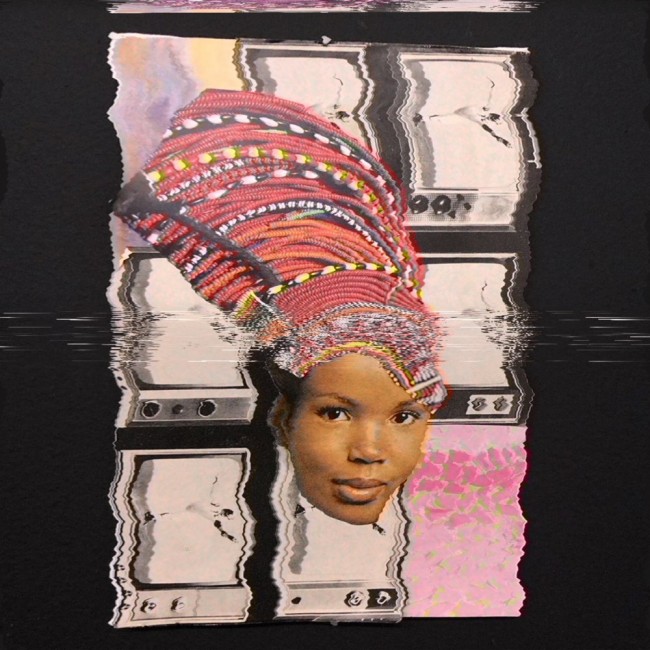

INTERVIEW: Joar Nango On Indigenous Architectures And Slippery Identities

Joar Nango’s identity as Sámi, the Indigenous people of northern Europe, is central to his art and architecture practice. Yet in terms of discipline or medium, he actively defies categorization, choosing instead to mobilize the space in-between and across worlds. This is partly to find breathing room within his creative practice and partly political stance — strategic evasion as post-capitalist critique. Through site-specific installations, video, and zines, Nango actively investigates intersections between Indigenous and contemporary architectures, traditional Sámi construction, and new media. The results have a way of escaping the present; instead, they create a kind of feedback loop between past and future architectural narratives.

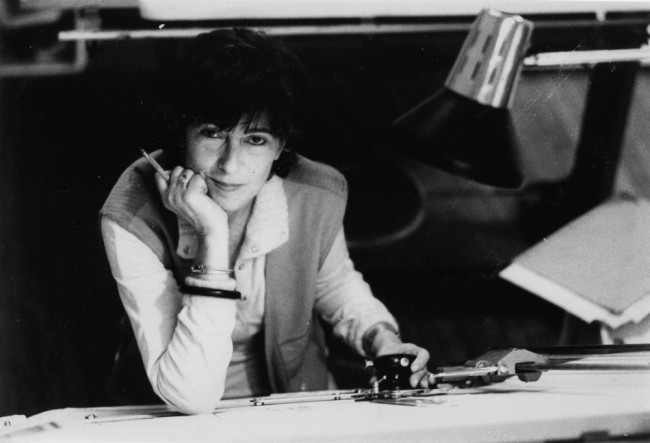

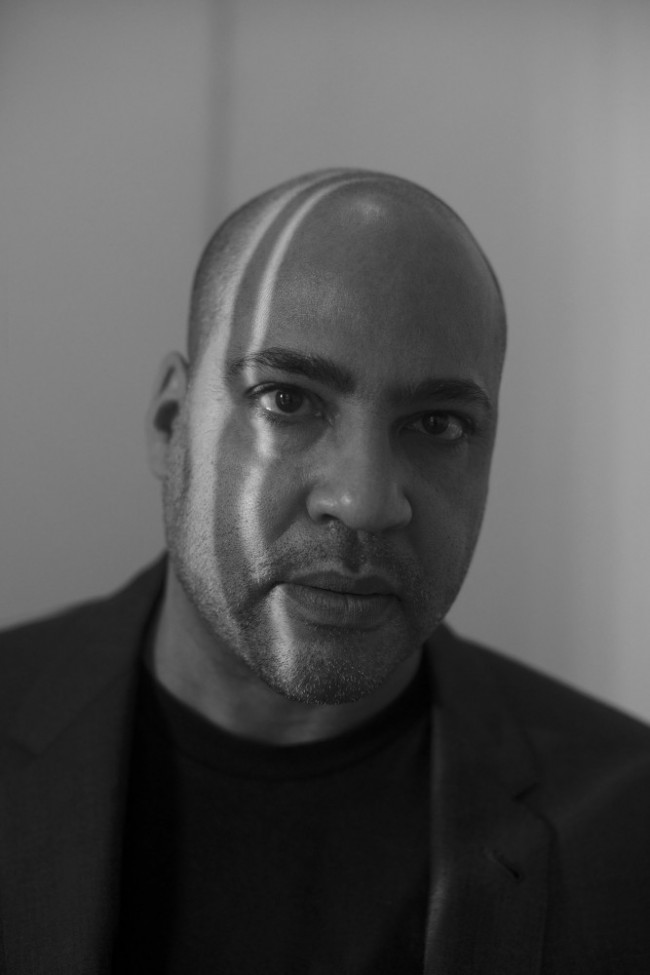

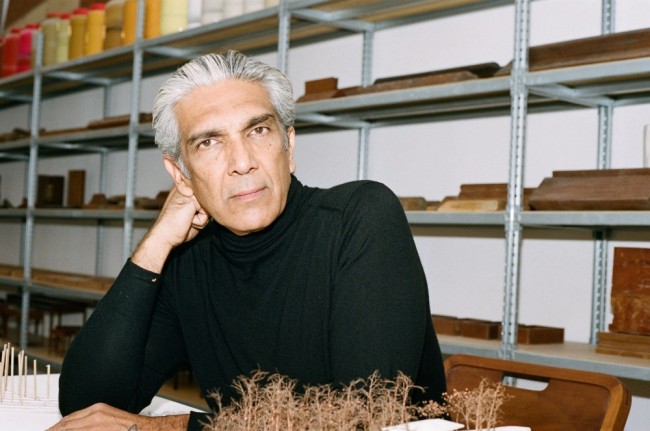

Joar Nango photographed by Pernille Sandberg. Courtesy of Joar Nango.

His work, often collaborative, has been shown at Documenta 14, the 2019 Chicago Architecture Biennial, and is currently on view at ArkDes in Stockholm as part of Kiruna Forever, curated by Carlos Mínguez Carrasco. For the exhibition, which brings together more than 100 artists and designers to reflect on the moving of the city of Kiruna in northern Sweden due to the expansion of an iron ore mine, Nango contributed a video recording of a seminar he conducted on Sámi architecture, gathering together the community of Sámi architects. The museum also commissioned him to develop a new iteration of Girjegumpi, a nomadic Sámi architectural library with over 200 titles addressing issues relevant to Indigenous architecture, resistance, and decolonization. The installation will open in Kiruna this August, pandemic permitting. PIN-UP reached Nango in Tromsø, a town on the far northern coast of Norway, via Zoom.

Girjegumpi, a nomadic Sámi architectural library by Joar Nango in Jokkmokk, Sweden. Photography by Ingrid Fadnes. Courtesy of Joar Nango.

Mimi Zeiger: For the ArkDes exhibition Kiruna Forever, you’re showing a four-hour long video of a seminar in which you bring together Sámi architects of many ages with different practices as a means to generate new knowledge. Tell me about the pedagogical side of your practice and the need to bring Sámi architecture to light.

Joar Nango: When I graduated, I was one of only three Sámi architects. So, I started to look for others. I very easily tracked down two of them, and it took me a couple of years before I tracked down a fourth one and a fifth one. It’s been quite a while since graduation, and newer, younger architects and designers have appeared and have thoughts about what the genre “Sámi Architecture” could mean. I think now we’re maybe eight or nine Sámi architects worldwide and that seminar was the first attempt to really gather all of the voices involved to discuss this topic and, of course, to build community.

I’ve always been in between art and architecture. I studied art and architecture parallel from a very young age. As a student of architecture — I have a master’s degree from Trondheim Technical University — I remember being very upset about the lack of interest and the lack of attention given to colonial aspects of architecture. Colonization and architecture are not separate phenomena. They are always entangled in the same political narrative. During my time studying, there were almost no perspectives offered on these issues. The curriculum reflected a contemporary idea of architecture as a political neutral discipline without any responsibility to question the underlying power structure it is a part of. All things dealing with Indigenous or Sámi issues had this folkloristic and totally outdated perspective to it. I was personally provoked by the lack of discourse around Sámi or Indigenous architecture in a contemporary context.

I grew up with a Sámi identity and was always aware of my roots and family in Sápmi (territory in the north of Norway, Finland, Russia, and Sweden). But at the same time, because I grew up both in the north and in the south, I moved between cultures, the way many of us younger, Indigenous educated people of my generation do — you carry both your background, but also influences of contemporary culture, like urbanity and everything that brings.

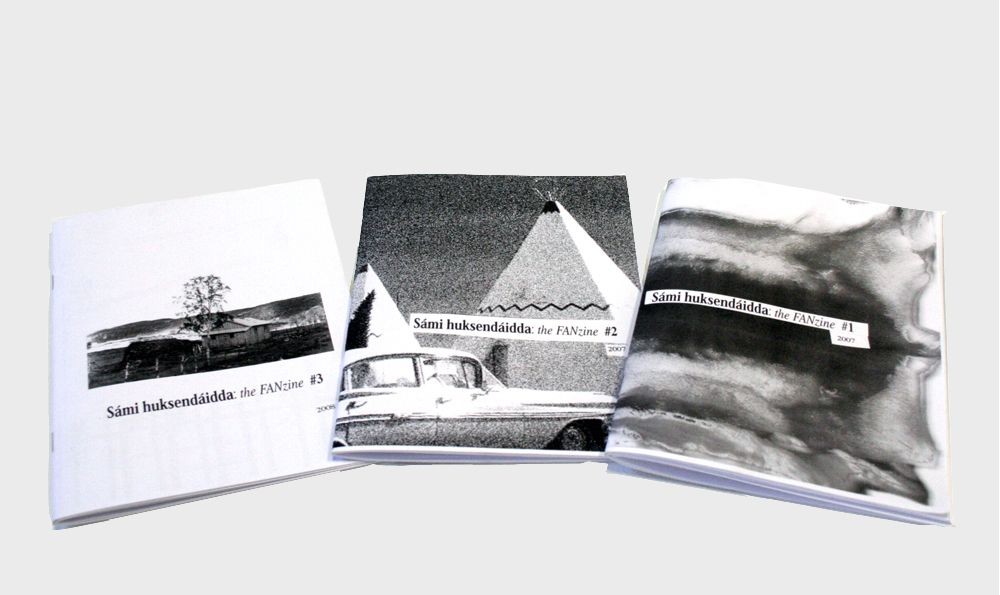

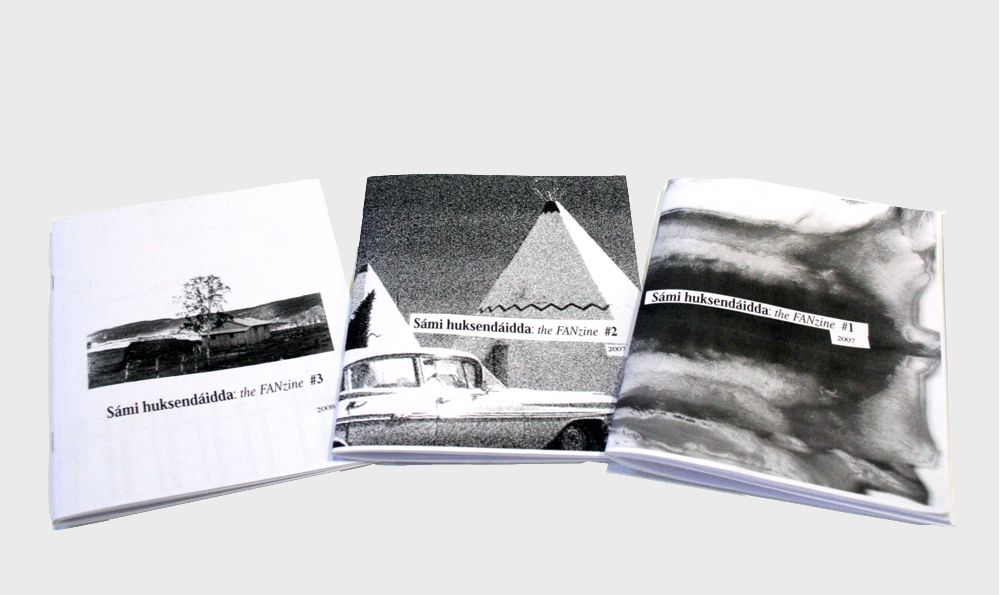

Sámi Huksendáidda (The Sámi Art of Building), a four-issue zine on Sámi and Indigenous architecture launched in 2007. Courtesy of Joar Nango.

As a consequence of the lack of attention on Indigenous architecture, I started studying it and that work became my master’s thesis. I was like very, very deep into the topic. As soon as I graduated, the University invited me to teach. I was starting to open up some new chapters in a complex history, so I started to do workshops with students as well. I also started to do projects that, I guess, have a pedagogical kind of dimension to them. One of them is a magazine called Sámi Huksendáidda (The Sámi Art of Building), a home-grown, zine-style publication, which came out in four issues. It deals with Sámi and Indigenous architecture. I was the editor, but I also invited other perspectives into the magazine, to create a polyphonic narrative around these issues — to create a conversation.

I also started an architecture zine. I like that you’re calling Sámi Huksendáidda a zine because it captures a particular ethos of politics and hands-on production. Why was the zine format important?

That’s a good question and I feel excited to answer it because it’s also a personal thing that’s connected to my background in underground culture, comic books and being involved in mixtape culture. I’ve made mixtapes my whole life. I’m a music geek, and I just like collecting and gathering and creating. I like the autonomous control that you have through that medium. But what I like most of all is the aspect of borrowing. Once in the 1980s, Morrissey said to the media: “Talent borrows, genius steals.” It was a quote he stole from Oscar Wilde. And there’s something really interesting about the way a DJ works — the way that a lot of our contemporary culture does as well. Sampling entered hip-hop and techno music, and music is based on other existing musical sources.

Zine culture is a predecessor of Internet culture. It is cut-and-paste technology — a very hand-to-mouth, lowkey circulation of things. You avoid all these very strict ideas about copyrights and it’s also a little bit further away from the idea of strong individual authorship. It’s much more about creating a collective narrative. So, there’s a lot of things in zine culture that are the core values of how I’ve been working: found materials, the idea of scavenging, and the idea of — I wouldn’t say steal — of somehow re-appropriating Western thinking into Indigenous thinking.

Girjegumpi, a nomadic Sámi architectural library by Joar Nango at Márkomeannu, a cultural and music festival in Northern Norway. Courtesy of Joar Nango.

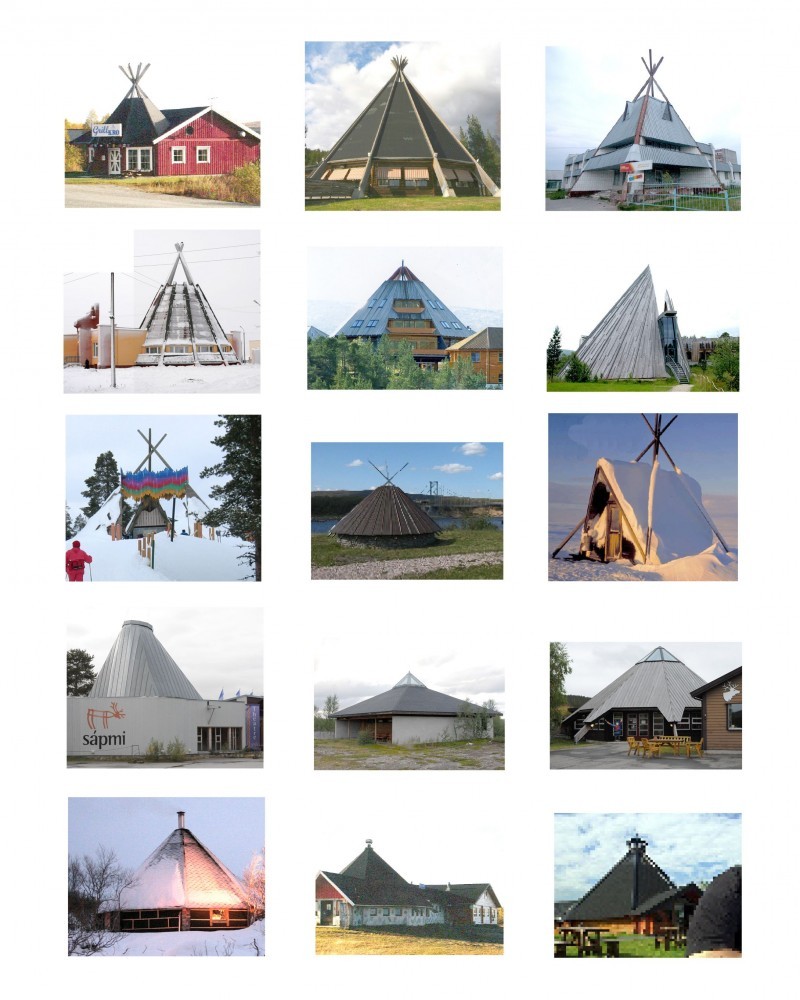

In a talk in Bergen you said that when architecture relates to culture or minorities, it draws on ethnic symbols. How does that fuel your counter movement and research?

If you open a book on architecture, there’s no chapter on Sámi architecture. You’ll find absolutely nothing there. Or like half a page of ethnographical images from the 18th century. But Sámis have a society, we have a political system with a parliament. We have cultural houses, we have schools. It’s small, and it’s fragile, very fragile, but we have it. And, of course, connected to all these institutions that we managed to build up over the last forty to fifty years, there’s some elements of architecture as well.

As I researched these buildings, I found that they were mostly designed by Norwegians or other non-Sámis. (To this day, there are no Sámi institutions designed by Sámi architects, even though we have Sámi architects.)

All of them unfamiliar with Sámi culture, they entered the Sámi culture and were inspired by its exoticism — our traditional music which is spectacular, clothing and our traditions. And certainly, there are some parts of our culture that are very exotic: the reindeer herders, these nomadic people living in closeness to the reindeer movement on the land. Of course, the architecture connected to this culture is nomadic, and we have a structure called lavvu, which is our kind of tipi.

And we have some different versions of that, but the most iconic form is kjegle, or cone-shaped. It’s geometric — a very strong primal archetypical shape that stands out over landscapes, so of course, all the architects were totally stunned by it. And then they all did the same thing. Without too much architectural ambition, they took the lavvu form, and they grafted it on to a conventional type of contemporary architecture without trying to decipher the real cultural concept, or even the spatial concept that this Sámi space carries with it.

Sámi lavvu-inspired architecture by various architects. Courtesy of Joar Nango.

It’s very Learning from Las Vegas — Venturian. I was disappointed because I thought that it was such a simple way of designing, using all these strong ethnic symbols. I took photos of and mapped 50 or 60 of these buildings. They’re discotheques, they’re libraries, they’re restaurants, they’re hotels, they’re blacksmiths, they’re shopping malls, they’re railway stations. Even the Sámi parliament building has that same form. I coined the phenomenon “Giant Lavvu Syndrome” because I wanted people, especially Sámi people, to discuss this. And I wanted architects to see that they all are doing the same thing.

And I wanted the Sámi people to also be aware of what architecture does to us and who is represented through architecture. What do we want as a Sámi people? Do we want to be exotified at every moment or do we want to try and develop our culture? There are so many super interesting spatial concepts within the nomadic Sámi reindeer herding culture that can be adapted into a contemporary architectural design. The Giant Lavvu Syndrome is like upscaled Learning from Las Vegas symbols. You know that duck?

Yes (laughs).

That duck building selling the deep-fried duck. So, this photo and mapping project, which I included in my zine, also took another turn, and it became a knitted sweater project. I wanted to take that idea of building back to the first layer of architecture, which is clothing. I took the most beautiful images and I made a knitting pattern for sweaters depicting these buildings. I contacted some elderly knitters from the villages where the buildings are located, and they worked with yarn from the west coast of Norway — from a 200-year-old business making this wool and yarn in beautiful colors. It’s humorous, but also social, and in a way gentle, trying to somehow complete the circle.

Knitted sweaters by Joar Nango and local knitters. From the show Among All These Tundras at Cosmoscow in Russia, now touring in Canada. Courtesy of Joar Nango.

These days, you call yourself a Sámi architect, but yet you operate more in art circles. I’m curious about how you position yourself. Are you interested the global architecture conversation?

I have an interest in both fields, and it’s always not up to me to choose which direction a project takes. I don’t need to define, to make a distinction between art and architecture. The topics I work with are always grounded in this interest that I have for architecture. But then, you know, I’ve done art, and I’m hanging out more with artists than architects. I like artists better, usually.

They’re more fun.

Totally. They’re more free-thinking and more fun to hang out. So, I don’t distinguish so much, but I do think that playing around with identities or categories is sometimes something that I do. There’s something about that evasiveness, and there’s something about that flexibility and constantly avoiding getting framed too easily that I think mirrors identity discussions that I’ve been involved in from a Sámi perspective or an Indigenous perspective. As Sámis, we’re really quite used to trying to slip away from this colonizing gaze that, through an anthropological lens that tries to understand us as this or that.

There’s some kind of a power that exists within the gap between art and architecture that I am able to utilize through my background. There’s this space to exist between categories, which is like, for example, when I meet an architect, I can say I’m an artist, and when I meet an artist, I can say that I’m an architect. And through that, I can avoid being defined by their perspectives, but I can create my own a little bit more freely. By working with Sámi architecture or working with Indigenous architecture, I think that there’s a freedom that comes with being released a little bit from the history of European or colonial architectural history. By being directly infused into contemporary decolonializing narratives, we can remove ourselves and not be defined by the old histories. And that has a lot of potential.

I’ve been fascinated by these kinds of slippages and nonbinary territories because they seem to produce different kinds of aesthetics and allow alternative ways of thinking to emerge. I appreciate what you are saying that this might be a technique of oppressed or colonized people.

Yeah, I’m very interested in this nonbinary thinking and queer theory. I have been having conversations about these things with other colleagues of mine for a long time already and I find a lot of inspiration in them.

-

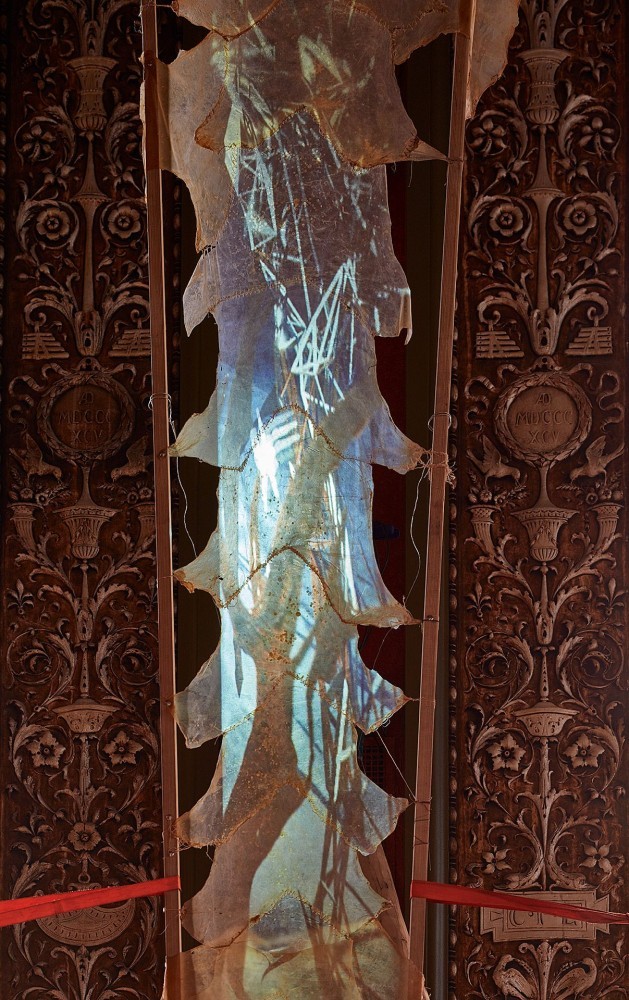

Halibut stomachs used in Joar Nango's Skievvar at the 2019 Chicago Architecture Biennial. Courtesy of Joar Nango.

-

Halibut stomachs used in Joar Nango's Skievvar at the 2019 Chicago Architecture Biennial. Photography by Tom Harris. Courtesy of Joar Nango.

I was taken by your piece Skievvar at the 2019 Chicago Architecture Biennial, with its juxtaposition of dried and stretched halibut skin and media projections. For me, the piece spoke of a way forward for architecture — a kind of ancient futurism and new set of vocabularies. It reminds me of a trajectory of misuse, ad hoc, or DIY within architecture Such as Charles Jencks’s Adhocism and Reyner Banham evoking bricolage. Is it at all useful to frame your work within that tradition?

As I said before, I shop and steal and find inspiration everywhere. And it’s not like I’m not going to read something because a guy from London created it. Adhocism, that book is like a bible for me. I had found it already when I was a student. And it was like one of the first things that really opened up this idea I call “indigenuity.” Indigenuity is a combination of the word “ingenuity” and “indigeneity”. So, “indigenuity” as a wordplay is an attempt to coin “adhocism” or “bricolage” through a decolonial or even politicized lens.

I started The Indigenuity Project together with an artist and designer named Silje Figenschou Thoresen. We looked at contemporary nomadic spatial concepts, which are remains from old cultural philosophies and livelihood philosophies, Indigenous philosophies, which are all about surviving and solving problems at the spot when they occur. There’s this attitude almost of thinking fast at the spot when you need to think fast. And you see every object or every material around you as a potential problem-solving material, which really explodes the idea of the commodity and the consumer mentality. It’s a way of seeing objects and materials as something else, as something more, and giving them more value, or giving them some kind of a philosophical value.

Reindeer herder sled from The Indigenuity Project by Joar Nango and Silje Figenschou Thoresen. Courtesy of Joar Nango.

Exactly. So many projects within the last decade or so operating through this kind of architectural assemblage have been capitalized and instrumentalized for the service of making spaces better in the city or ways of decorating your apartment. What’s interesting in your definition is the way that the object itself is given agency, not the use. The use is fluid, but the object itself is the actor, which is a different take.

There’s something about the attitude that’s connected to the idea of the vernacular, and there’s something very fragile about that kind of concept when it’s entered the world of specialized designers and specialized thinkers. There’s a risk of removing these objects and ideas out of an original context. If it’s done too much, I feel like it’s losing a lot of its existentialism — or agency — as you said. Charles Jencks does that a bit. By making that book, by framing it the way he does, by talking about it the way he does, by intellectualizing it.

I’m trying to work with this attitude to incorporate the connection between context and the agency of the object. I’m trying to not separate them or pull them apart — that’s what the architects always do, for some reason. Like, very often designer architecture considers nomadism as something placeless, or something that’s traveling between airports or coffee shops. But for me, nomadism is the exact opposite. Nomadism is the ultimate site-specific concept. It’s really what is so connected to the site. And that’s what “indigenuity” is for me. It’s that ultimate connection between man, building, and context or place. So, I’m very conscious about that, and I feel like what I’m working with is always trying to reach into the place and the site.

It seems like we could slide very quickly into a reductive discussion of the aesthetics of the logs, reindeer pelts, and dried halibut stomachs as a kind of an aestheticization of Sámi Indigenous culture. To what degree are you inviting that conversation? To me, what’s interesting within your work is how those elements are often juxtaposed with more contemporary elements like video or other kinds of new technology.

I think that many of those elements are for many people, very exotic. Because for us up here, this is not exotic at all. You know, like using reindeer skin to sit on — that’s what we do. Because it’s the fucking best technology that ever was made. People make inflatable plastic beds, things that you can sit on or sleep on in tents, and it’s such an amateur technology compared to the beauty of the reindeer skin, which are accessible when you have family that do reindeer herding. You get them (almost) for free — you just dry them, they last for many years, and it’s a super sustainable way of using all the parts of the animal. There’s no oil being pulled out of the ground, processed into some commercial product that’s shipped to China and then back again in order to reach a destination. It’s never even entering a monetary system.

Dried halibut stomachs used in Joar Nango's Skievvar at the 2019 Chicago Architecture Biennial. Courtesy of Joar Nango.

The reindeer hair itself is hollow, so it’s basically perfect insulation. It’s made for keeping animals warm and keeping heat in or out. It’s a much softer, more heat-preserving surface than any other animal pelts or skins. So, there are many aspects to it. It just doesn’t make sense to not use it, and then someone at an art biennial thinks it’s exotic and makes judgements. Should I stop using the most brilliant technology because someone thinks it’s exotic? It doesn’t really make sense. Reindeer pelts are very practical, accessible, and cheap. And they’re totally ecological. It’s a conversation that goes back to ideas of context.

I really appreciate you making that distinction because as you describe it as something outside of flows of capital. It locks into an ecology, it locks into a place, like I think that enlarging that whole picture and conversation around materiality seems important at this point in time.

I’m not interested in being nostalgic and stepping back in time in order to romanticize the past. It’s not what I’m doing at all, so I’m very interested in also following up what technology can offer to a space, and then I’m very interested in the light way, extremely digital formats that come through technology and digital formats. I’m very interested in how colored light and moving light, and also how sound digitally composed music from field recordings can become spatial elements, almost architectural components. And that’s something that I’m just as passionate about as the reindeer felt from my uncle. So, I don’t really distinguish one from the other. It’s natural attraction and also they’re both part of my natural world.

Interview by Mimi Zeiger.

Portraits by Pernille Sandberg. Images courtesy of Joar Nango.