INTERVIEW: Tezontle Studio Unearth Mexico’s Pre-Hispanic Past Through Architectural Abstraction

Neither quite an art practice nor an architecture firm, but rather an open-ended amalgam of both, Tezontle was founded almost unwittingly by architects Carlos H. Matos and Lucas Cantú in Mexico City in 2015. What began as two individual designers looking to share a workspace in the historic center developed organically into a cohesive intellectual vision, born from their mutual appreciation of the forces and forms that physically shape the world around them — an appreciation encapsulated in the studio’s very name, tezontle being a reddish volcanic rock that is used all over Mexico in everything from cinder blocks to road surfaces, and from which many of Mexico City’s historic buildings were constructed. Though born in the city, Tezontle was forged in the jungle of Las Pozas, Edward James’s Surrealist garden estate of concrete follies 200 miles north of the capital. It is there that Cantú and Matos, together with two colleagues, co-teach a summer workshop for the Architectural Association (see PIN–UP 21). Inspired by James’s example, the duo experimented with concrete and formwork, the material research at Las Pozas becoming the basis for Tezontle’s ethos, which Cantú and Matos have gone on to develop in projects across Mexico, as well as in California and Cuba. As the duo’s output slowly evolves from mostly art installations to their first houses (they just finished one in Tulum and are working on another in Oaxaca), they remain attuned to the ways that the built environment reflects the fragmentations of history, and attentive to how we fill in the gaps between these fragments with all sorts of myths, constructs, and inventions.

Carlos Matos and Lucas Cantu of Tezontle, photographed by Dorian Ulises López Macías for PIN–UP.

Tezontle’s ideas and your common values seem to have been able to develop because you were searching for a home. Could you tell me about how Tezontle was formed?

Carlos H. Matos: Well, Lucas originally asked me if I wanted to share a workspace in the historical center of Mexico City in 2014. And we ended up looking for over a year. We’d meet once a week to scout things out.

Lucas Cantú: These walks became an exploration of downtown Mexico City as a potential place to work. We started talking a lot, comparing our references. And we kept asking ourselves, “Why isn’t anybody looking at all of these beautiful colonial and pre-Hispanic parts of Centro?”

CHM: It was only when we eventually found our space that we realized we weren’t just going to share a studio space, but actually that this studio was Tezontle.

LC: Finding our space was very important for Tezontle. It catalyzed a lot of our ideas and everything just started to make sense. We like to think of the studio as a fun house. It’s where we go to have fun and where we can be open. We throw parties here, we have concerts. We’ll have artists come in and do exhibitions here, too. So there’s a lot of cultural activity in the studio.

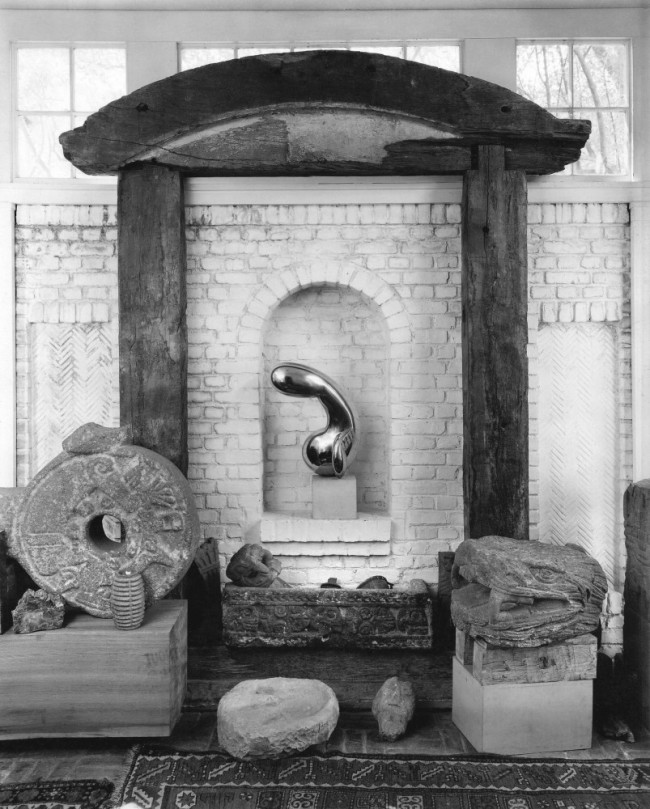

CHM: We wanted the space to be somewhere you wouldn’t want to leave. We didn’t want it to be a stereotypical architectural practice with rows of computers and perfect models on display. We wanted it to be this ever-changing cabinet of curiosities. We’ve collected a lot of artifacts and you often can’t tell which ones are valuable from the ones that are literal rubbish. Everything is put on the same level. We have what are actually very rare archaeological pieces sitting next to a lump of concrete or something. That makes us bad museologists, maybe, but we see it as a spontaneous way of looking at history. We try to look at it humbly, somehow.

LC: A key part of the creative process here at Tezontle is the collecting of objects that start to inform each other. Here at the studio, we make a lot of these collage worktables that are kind of like shrines or arrangements. This is where we start to really see materiality. We’ve also been putting together a library of around 1,000 books, mostly focused on Mexican history. And even though we don’t have the time to read them all, they impart a kind of intellectual aura to the space.

-

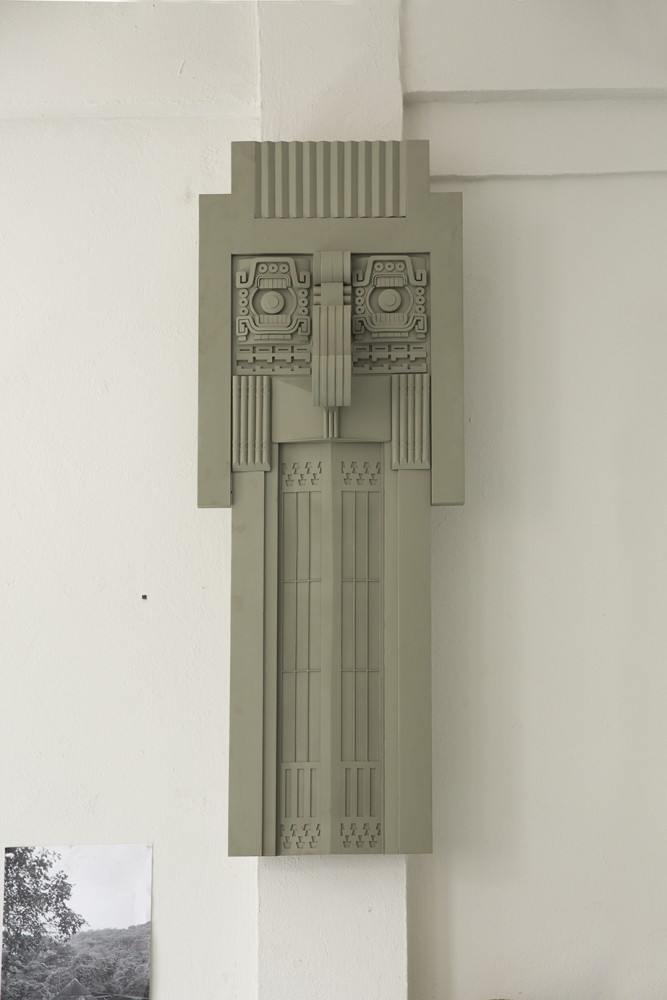

View of Tezontle’s studio in Mexico City’s Centro Histórico featuring, among others, the sculpture Columned Egg (2016), cast in MDF, steel, and cement. Photograph by dorian Ulises López Macías.

Can you explain why Mexico is so important for your practice?

CHM: Mexico is quite an interesting context. For better or worse, it doesn’t have much fear of reinventing itself. This means that you can end up with Modernist masterpieces being demolished to build shopping centers, but, on the other hand, there is so much liberty. It has always been an architectural playground. Like Félix Candela who did his shell structures here in the 1950s — structures that would probably have been too experimental for Europe at the time. So this is not a place that is stuck in the past. It’s always been a place that allows for freedom and for that destruction. And perhaps people might not be as aware of this past as in other places, but this also allows them to be more spontaneous. I think that Mexico City, at least, tells such an interesting story about identity and its constant reinventions. It was, after all, only with Modernism that we even started looking back at the pre-Hispanic as being relevant to our history. And of course while it was being reappraised, it was also reinterpreted.

LC: We’ve taken a lot of field trips to the anthropology museum and so much of the information there on the pre-Hispanic past is very vague. It’s almost as if Mexico is an archaeological abstraction with only a few facts and hints. And in this in-between there is this speculative fantasy, a sort of fiction that has been used to form our understanding of who we are. At Tezontle we play a lot with this kind of speculation. We’ll make these abstract sculptures that experiment with the pre-Hispanic aesthetic, but in a really fantastical way.

An abandonded tezontle quarry in the Mexican state of Morelos. Quarries like these provide different strata of tonalities for sourcing and sampling Tezontle’s studio in Mexico City. Photograph by Carlos H. Matos.

Your exploration of the city and its history also seems to overlap with your material experimentation.

CHM: In many ways, Tezontle was imagined as an extension of the experimental thinking we’d developed during the workshop in Las Pozas. I had started it along with our other two partners, the architects Umberto Bellardi Ricci and Kanto Iwamura. Lucas actually joined us in our second year. We proposed this idea to the Architectural Association because there were already visiting schools in Mexico, but they were all digital, software-based. And we thought that Mexico would be perfect for doing the exact opposite. We wanted it to be very hands-on.

Section model of Space We Never Knew (2016); Pigmented cement. Photograph by Rodrigo Chapa.

Did you choose to work in concrete at Las Pozas because of its existing follies or due to the limitations of the site?

CHM: Concrete was a very intuitive material to work with in Las Pozas. But actually I think that our interest in this material comes from Mexico City, where we were already looking at all of these precedents of large-scale sculptures commissioned in concrete.

-

Portrait by Dorian Ulises López Macías.

-

Portrait by Dorian Ulises López Macías.

In his seminal 1955 essay “The New Brutalism,” Reyner Banham talked about “valuation of materials for their inherent qualities ‘as found.’” It makes sense to me that, in the spirit of Banham, you started to experiment with concrete for its inherent qualities, but you’re also not limited to just that one material.

CHM: Absolutely. Brutalism is not exclusively affiliated with concrete. This is often assumed, but it’s really about exposing the sort of primary essence of any material, and we’re always eager to experiment with different materials like rubber and fiberglass, and plastics, like Nylamid, as well as aluminum and other metals. But the reason we like concrete especially is because we think Mexico “speaks” concrete — it’s deeply ingrained in the culture. Las Pozas was our initial attempt at recreating this kind of non-programmatic, sculptural architecture that has a strong presence in Mexico. From the sculptures of Mathias Goeritz to the architecture of Juan O’Gorman, and even the house my grandfather (Ernesto Gómez Gallardo) built, all of these structures were made entirely of concrete. They were not necessarily designed to be functional, but they’re incredibly poetic. And we wanted to see if it was possible to make this kind of experimentation relevant to architecture again.

LC: At the same time a lot of people have this misconception that we are experts in concrete. We even get calls from people asking us for advice. But our concrete pieces are actually very experimental. And we work with sculpture because it doesn’t have the same constraints as architecture and we can try things much faster. We might add some charcoal to the mix, for example, just to see what happens — you could never do that with a building because if the concrete isn’t mixed right then you could essentially kill people. So we have the freedom to do a lot of experiments but we will only take some of that into our architecture.

Piedra 3 – Piedra en su Molde (2017); MDF, wood, pigmented concrete. Photo by Nydia Cavazos. Courtesy Peana Projects, Monterrey, Mexico.

So there is not necessarily a functional goal to your formal and material experiments?

LC: No. There are architectural resources in our sculptural work and vice versa. One thing will lead to another as the practice moves forward. We go back and forth between the disciplines of art and architecture, and between the functional and the functionless. And even an experiment that doesn’t “work” could still result in the development of a more technically appropriate material for a structure.

CHM: Concrete has worked nicely for us because we don’t only see it as a material for construction but also as a sculptural material that can be ornamental. And we’re now trying to do as much with other materials that are used in architecture. We’ll often make multiple, modular pieces. With every cast we might add a material like car filler or something to soften the surface. Then we might add a glue. And the end result is a very beautiful patination of the mold. We find inspiration in the casting process. We are drawn to materials that have grown a patina over time. I don’t think we ever really do anything new — in fact, I think it’s almost an impossible task to make something new. But things can be reborn when they are reproduced, like when we recreated some of Mathias Goeritz’s work, for example.

Or the work by Guatemalan-Mexican sculptor Carlos Mérida which you used for your 2017 installation at the Neutra VDL House in Los Angeles. Can you tell me more about that project?

CHM: We were invited for a residency at the VDL House to explore the relationships between Mexico City and Los Angeles. It was part of a project called Tu casa es mi casa, in collaboration with Mexico City’s historical archive, in which three Californian writers were each asked to write a letter to one of three Mexican architecture teams. Ours was from Aris Janigian and described a dystopian scenario where L.A. was being torn down and becoming completely dysfunctional. So we developed our project in response to the question that Janigian poses at the end of this text: “If modern architecture was about a kind of humble idealism, then what is going to happen in these times of protectionism and paranoia?”

LC: So we were looking at the glass pavilion on top of the Neutra VDL House and thinking about how we could convert it into a more protective structure, as a kind of bunker. It made sense to us to block off the fragile glass box and to convert it into something seemingly solid. So we decided to replicate a mural by Carlos Mérida, but instead of making it in concrete we fabricated it out of fiberglass, to make it translucent. It lets light through, but in a limited way. The fiberglass panels were then fitted into the original aluminum window frames of the Neutra VDL House, like a barricade. Its material qualities were intended as a bridge between the Modernisms in L.A. and in Mexico, via Neutra and Mérida. It was a very literal integración plástica of the Mexican mural onto Californian Modernism. Because the relief of the murals faces outwards, from the exterior you perceive a stone-like texture, but from the inside, these glowing chimerical mythological figures are revealed.

-

Exterior view of Rise and Fall, Tezontle’s 2017 installation at the Neutra VDL House (1932) in Los Angeles. The fiberglass panels were inspired by fragments of artist Carlos Mérida’s 1940’s murals from the Benito Juárez housing complex in Mexico City. Photograph by Lucas Cantú.

-

Detail view of one of the twelve fiberglass panels from Rise and Fall (2017) at Neutra VDL House in Los Angeles. Photograph by Lucas Cantú.

Which Mérida mural did you choose?

CHM: It’s actually not a direct copy of a Mérida mural, it’s more of a collection of many of the fragments of his murals from the Benito Juárez housing complex in Mexico City (Mario Pani et al., 1948–52). They’re collaged together and re-modulated according to the façade of the Neutra house. Our decision to use a mural was actually quite straightforward because murals were such a big part of the Modern movement in Mexico, and we wanted to imbue the Neutra house with the essence of Mexican Modernism.

LC: The crazy story is that the pieces for the Neutra VDL House were supposed to fly on September 19, 2017, the day of the most recent earthquake in Mexico City. Exactly 32 years earlier, in 1985, on that very same day, there had been another earthquake that devastated about a third of the city. Eerily, much of the Benito Juárez housing complex collapsed in the 1985 earthquake. There are some very powerful photographs of the original murals and all of the rubble after the earthquake

What a horrible coincidence.

CHM: Yes. We were in L.A. waiting for our crates to arrive when we heard the news. We were super hyped about the project and then this happened and we didn’t know if people had died, and we were just frantically calling friends and family. And we were also still trying get the mural to L.A., so we were calling these poor people at the airport who were saying, “I’m sorry, I can’t help you. I just lost my house.” We were trapped in limbo in L.A., sleeping in Richard Neutra’s room — it was very surreal and emotional.

In Californian Modernism, the glass box has always epitomized both a literal and a social sense of transparency. In Mexico this notion probably comes with a few caveats.

CHM: Exactly. If you look at the architecture of the Case Study Houses or the houses in Barragán’s master plan for the Jardines del Pedregal, their starting points were pretty much identical. But Mexico City evolved along a different path than Los Angeles and became quite insecure. And funnily enough, you still have these beautiful glass boxes in Mexico City, but they’ll be walled off in a huge garden. So you can be exposed to nature, but only your own private nature.

I guess even now the idealism underpinning Modernism is still not really appreciated — even iconic Modernist buildings are often spoiled or just torn down.

CHM: And in Mexico the erasure of Modernist history is even more common than in L.A. I honestly think that people in Mexico would be more devastated if they saw a colonial house collapse than a Modernist building. They wouldn’t see the irony in this.

Tezontle’s collection of prehispanic findings from Centro Histórico in Mexico City. Photograph by Dorian Ulises López Macías.

Do you see yourselves as part of that legacy of Modernist experimentation in Mexico?

LC: I like to think so. We are still in the process of discovering what Tezontle is. We never sat down and decided on an aesthetic or a way of working.

CHM: And Tezontle has been, how do you say, a very incubated practice until now. Our motivations and inspirations have all been made according to us, on our own terms. But there is an endless path of research and discovery, and it’s actually only now starting to make sense.

You recently spent time working in Cuba. Was that part of your research?

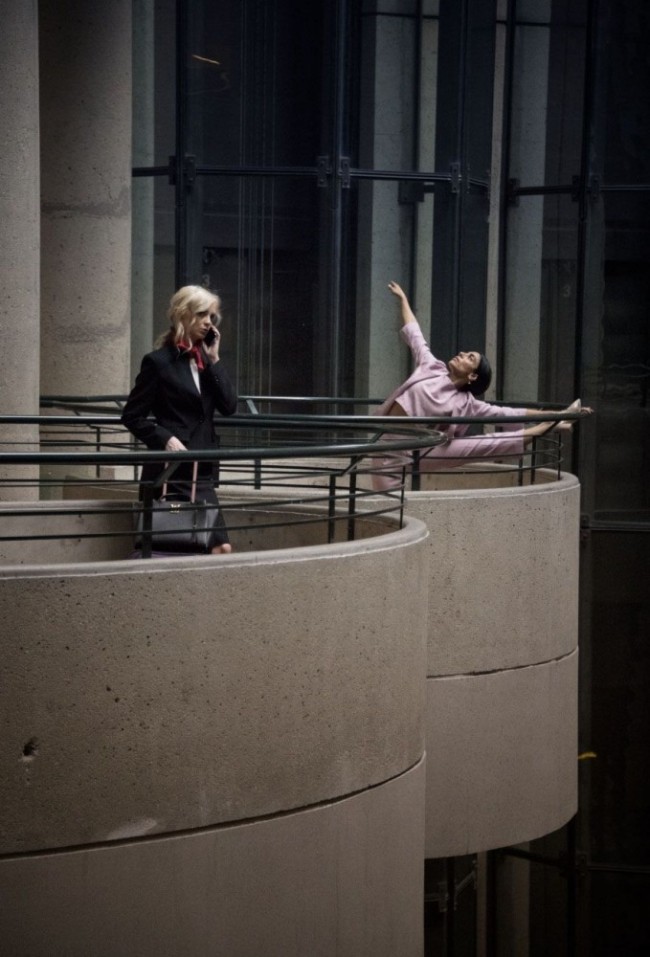

CHM: Yes, we were invited to participate in a residency program in Havana organized by the artist Wilfredo Prieto. We didn’t do Las Pozas this year so it was really nice to go to Havana instead. The city has a lot of abandoned buildings and a program to get artists to activate these spaces in cultural ways. Wilfredo has a big warehouse that he uses as his workshop, but his work is very conceptual and often doesn’t require such a big production. So he’s been using this space to host dance, poetry, and industrial-design workshops.

LC: We decided to explore the rust and the erosion that is everywhere in Havana. We assembled these extremely brittle samples and we were trying different materials, like this foam from a sofa that we soaked in very liquid concrete and let harden. This was an interesting material to combine with concrete because we could do very large-scale pieces with it. So it’s a process that I think we’re going to reuse in Mexico now.

-

Tezontle’s work from the Experimental Cycles program, a 10-day residency at artist Wilfredo Prieto’s studio in Cuba in June 2018. Photograph by Lucas Cantú.

-

Did you get to build anything while you were in Cuba?

CHM: No. But we were invited to come back and do an installation for the Bienal de La Habana in the spring of 2019. We proposed a temporary, modular pavilion made out of pre-fabricated concrete parts. The idea is for it to be produced all around Cuba and then assembled at a site on the malecón (Havana’s waterfront esplanade).

LC: The installation is going to trace the narrative of its own logistics, which can be a very complex experience in Cuba where there is still very little connectivity. We are going to use this amazing concrete that is Cuban-made. What’s interesting about this concrete is that it has a kind of brownish-yellowish color that changes depending on the soil that it’s produced with. So this will influence the piece. The individual components of the pavilion will be prefabricated in different parts of Cuba and then we’ll bring them together and put them on the Malécon.

CHM: They even offered for the pavilion to be permanent, which would of course be incredible. Through some periods of the year, the installation would be underwater because the tide will rise and submerge it. And it would have to survive these huge waves. There is something really interesting in thinking about how to create this intervention because Havana has a really strong identity, but it’s not always so contemporary. Basically nothing has been built in Cuba for the last 70 years. Cuba felt a lot like parts of Mexico to me, but frozen in time — it submerges you into a very interesting state of mind.

View of the veranda at the Todos Santos House, a project recently completed by Tezontle in Tulum, Mexico.

When thinking about the future, is Tezontle looking forward or back?

LC: Backwards! Always. (Laughs.) I think the future looks very bright for Tezontle, but when you look at the future, it’s totally unknown. So in terms of inspiration, we’re definitely looking backwards. We’re like archaeologists – we’re still discovering, because that is an endless path, and there are so many layers. When you look to the past, the amount of things that you can research is endless. And once you start you can’t stop.

Text by Daniel Simon Ayat.

Portraits by Dorian Ulises López Macías.

Taken from PIN–UP 25 Fall Winter issue.