MILANESE MAESTRO: Interview With Architect Umberto Riva on the Creative Power of Mistakes

Umberto Riva is the known unknown. In the world of Italian architecture, his name evokes the aura of a distinguished and wide-ranging oeuvre, yet his discreet style and the shifting nature of his vision — often compared to the work of an artist rather than of an architect — has ensured few people are fully aware of the specifics of his work. Eschewing both a “signature” and the “starchitect” ambitions of contemporaries like Renzo Piano, Riva has instead created spaces and objects that, in the words of Milanese architect Luca Cipelletti, are “elegant to the point of being unrecognizable.” His architectural career began in 1959, after studies in Milan and then in Venice under Carlo Scarpa, and has since embraced urban planning, interior and product design, and also painting. An expert draftsman — pencil sketches are still central to his process — and a keen observer of light and shadow — lamps and windows are defining elements of his practice — the 90-year-old is still working today: current projects include an annex to a home he designed almost 30 years ago in Apulia, southern Italy, as well as various design commissions through his gallerist Giustini Stagetti. Since 1998, Riva has also been a member of the venerable and distinguished Accademia di San Luca in Rome. The Serpentine Gallery’s artistic director Hans Ulrich Obrist met up with the prolific Milanese in his hometown to discuss his beginnings, his artistic inspirations, and the necessity of maintaining healthy suspicion with respect to one’s own work.

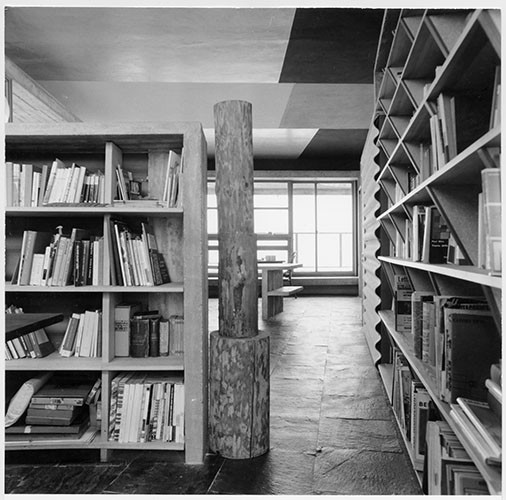

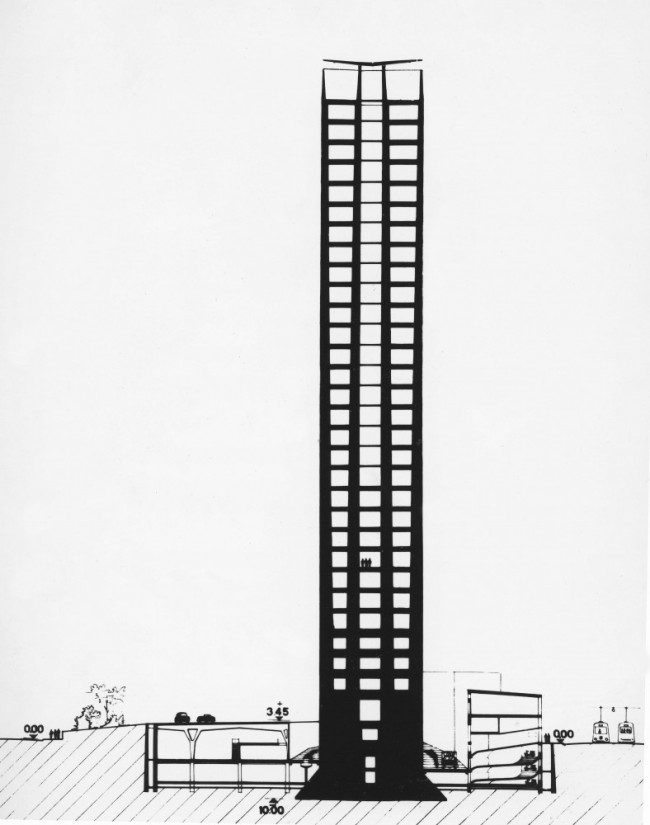

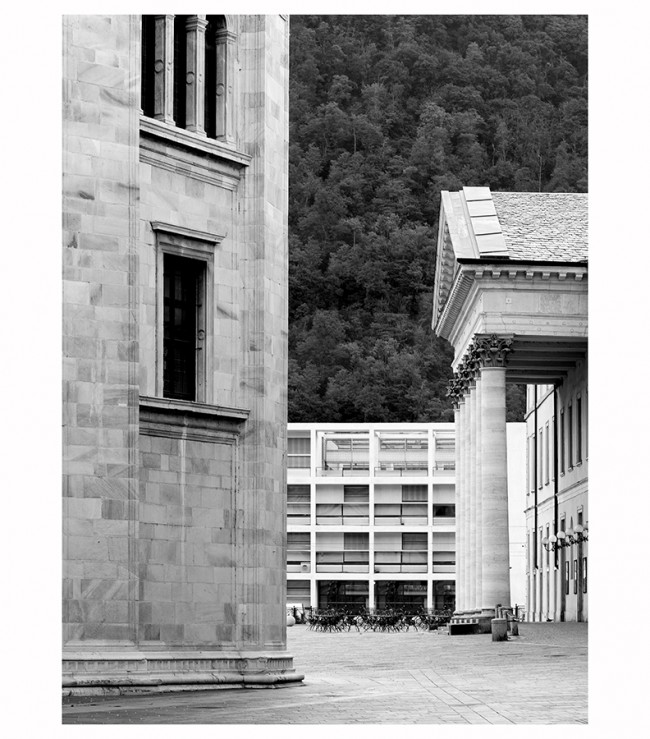

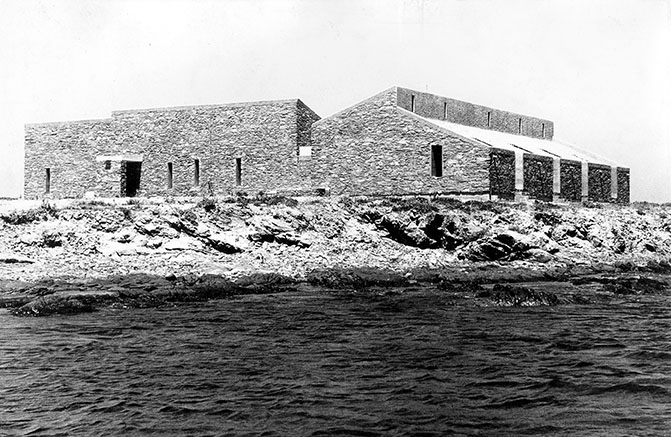

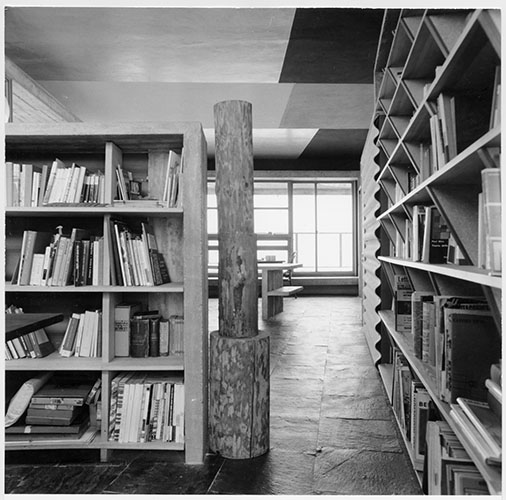

Case di Palma (1971–72); Stintino, Sardinia.

Hans Ulrich Obrist: How did you get into architecture? Or conversely, how did architecture get into you? Were you struck by an initial epiphany?

Umberto Riva: My initial encounter with architecture was tough. I was especially good at drawing, which is why I was introduced to the discipline in the first place. However, in high school I had studied to become an accountant, quite unsuccessfully. It took me as long as ten years to graduate in architecture, and I had three or four breaks.

HUO: Tell me about Carlo Scarpa, since you were one of his students.

UR: To me, Scarpa was an unrequited love. This was when at a certain stage I moved to Venice to study architecture for an extra five years, on top of the five years I’d already done in Milan. My life began the day I left university in 1959. I don’t want to tell you a weepy story, though. My work is constantly fostered and tested by my being in this world. Plus, there is the pleasure of making. I’m not really talking about manual skills — I can draw but I wouldn’t know how to put two chunks of wood together — I’m referring to the experience of making and the relationship with those people who are makers, both of which lead you to amazing discoveries, open up new horizons, and show you things you didn’t know before. It wasn’t easy in my case, because I had no idea whatsoever about the meaning of the width of wood or iron, or of their weight. In this respect, Scarpa was a great teacher for me — these were fundamental experiences.

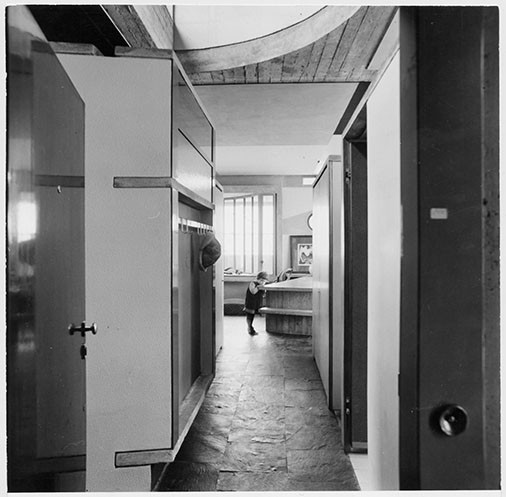

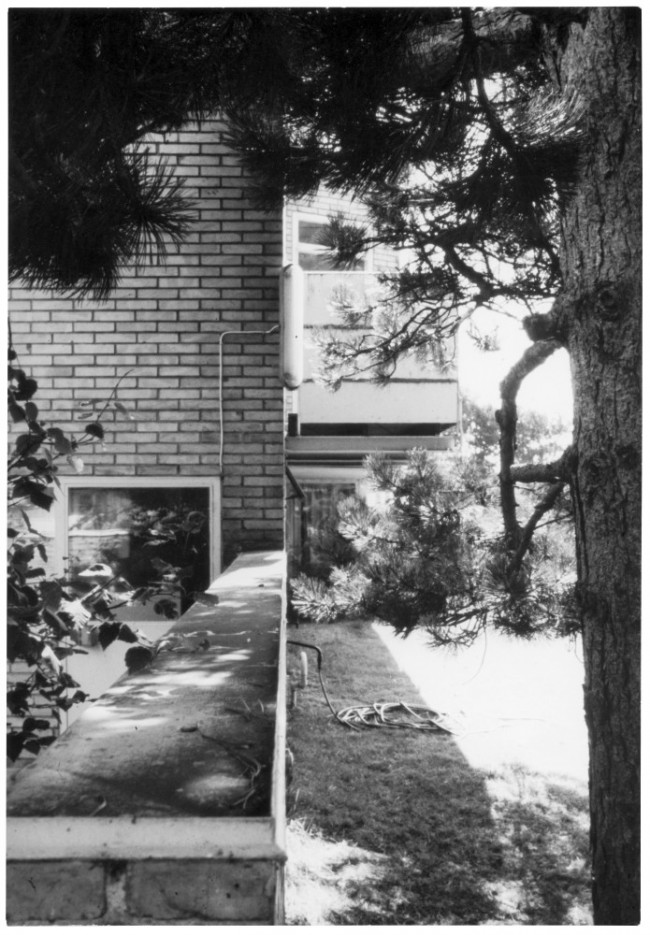

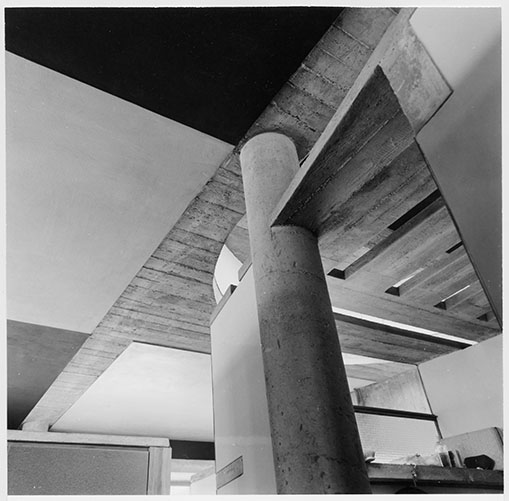

Casa Berrini (1967); Taino, Varese.

HUO: There’s a small book of correspondence by Rainer Maria Rilke titled Letters to a Young Poet, in which he gives out tips to a neophyte. If teaching art or poetry is a complex task, how does one teach architecture? What did you learn from Scarpa?

UR: The lack of immediacy in understanding your own value. His design method, and all of his buildings, were always cultivated and nourished by great knowledge. And in some way, this approach drew me closer to architecture through design, color, plasticity. In Scarpa, form is no longer punitive as it was for the Italian Rationalists, who mortified us because they turned living into an experience that was far from liberating. I was from Milan, and to me this was a surprise, because materials were suddenly revealed in a different light, with no fear of contamination. Scarpa’s museum project for the Palazzo Abatellis in Palermo (1953–54) or the restoration of the Castelvecchio Museum (Verona, 1958–74) are both great experiences, where one feels how important the contribution of time is. Visiting Castelvecchio and contemplating how cleverly it was floored is a little bit like walking down the Appian Way in Rome. It is a cultivated piece of restoration work, from which a sense of memory emanates. It isn’t just compelling on an emotional level, it also makes you aware of your limits and of the need to overcome them. Observing Scarpa’s glass plates, for instance, is a priceless experience, because what’s behind them is a whole culture of knowing how to handle material. It is no surprise to learn that he started working in a glassmaking furnace at a very young age. There is a kind of culture that one learns by making. I have no sort of abstract intelligence, but I do feel an irrepressible need to make.

-

Casa Berrini (1967); Taino, Varese.

-

Casa Berrini (1967); Taino, Varese.

HUO: And this is also true for art. You said your work doesn’t just draw inspiration from architecture, but also from artists such as Fausto Melotti or Constantin Brancusi. And you also practice as a painter.

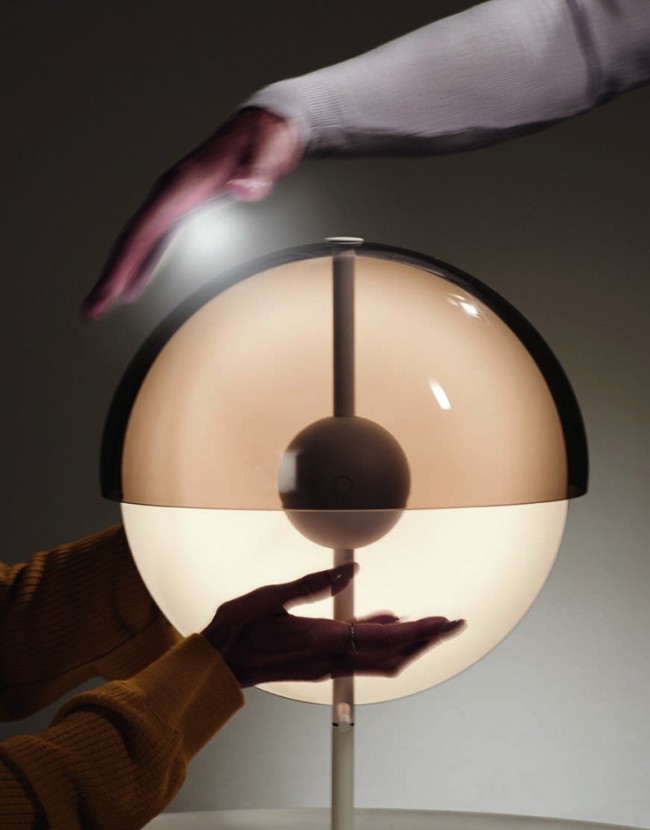

UR: As a habit, I used to paint whenever I wasn’t working as an architect. I advanced in fits and starts, approaching a painting several times, so much so that it would take me a year to finish one because life was going on in the meantime. I never understood anything at first, I always understood everything later. As for Brancusi, I don’t think there’s a word that is appropriate enough to describe his essentiality, richness, and knowledge of materials. It was he who inspired the E63 lamp (1963, relaunched 2017), which I initially named after him. I submitted it to a competition which required that the name of the presented project contained single letters that were not repeated more than once — Brancusi’s last name was perfect, but I still didn’t win.

HUO: Going back to your paintings: color plays a primary role in them, and the same can be said of your architecture. What’s your favorite color?

UR: Any color that needs the help of another color.

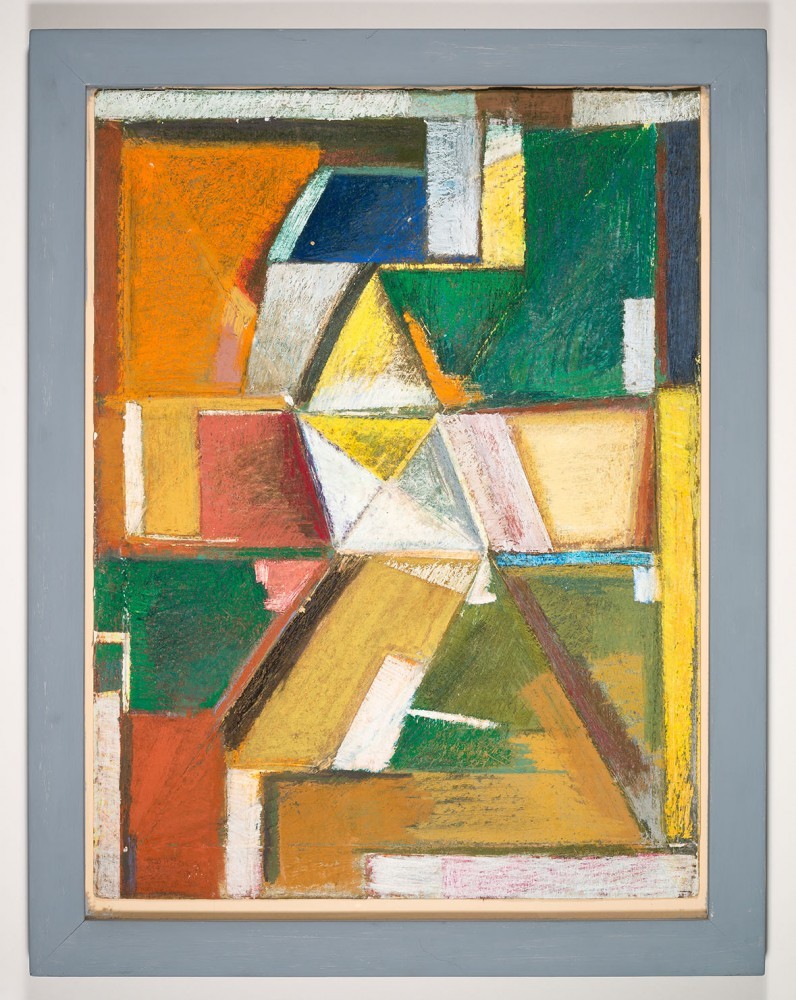

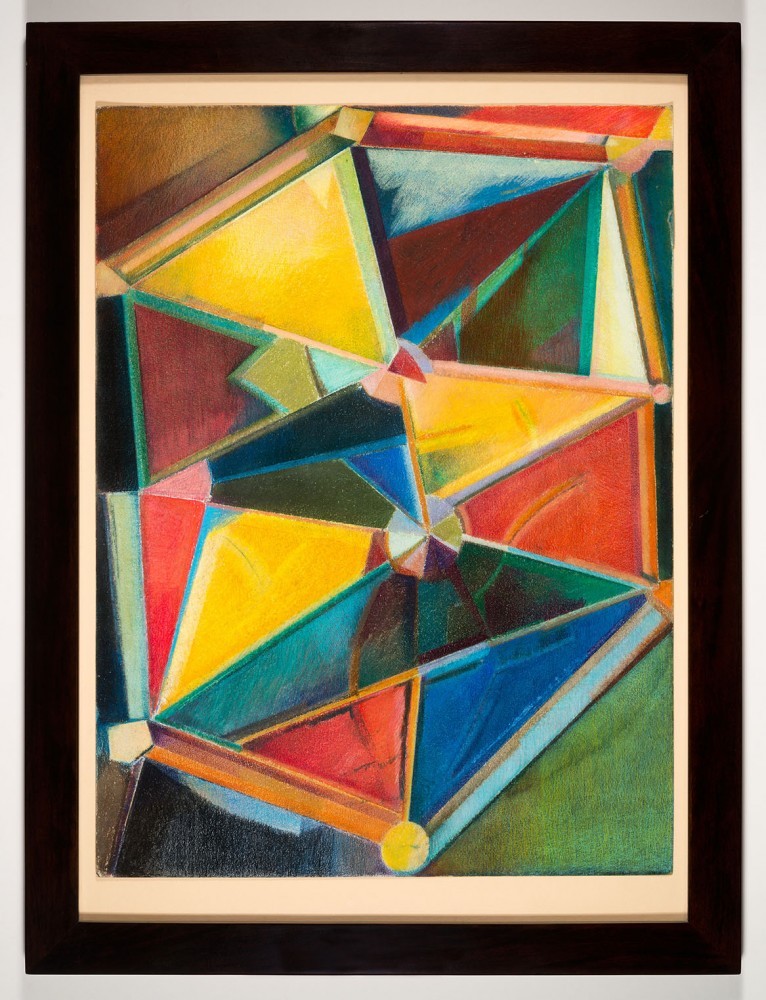

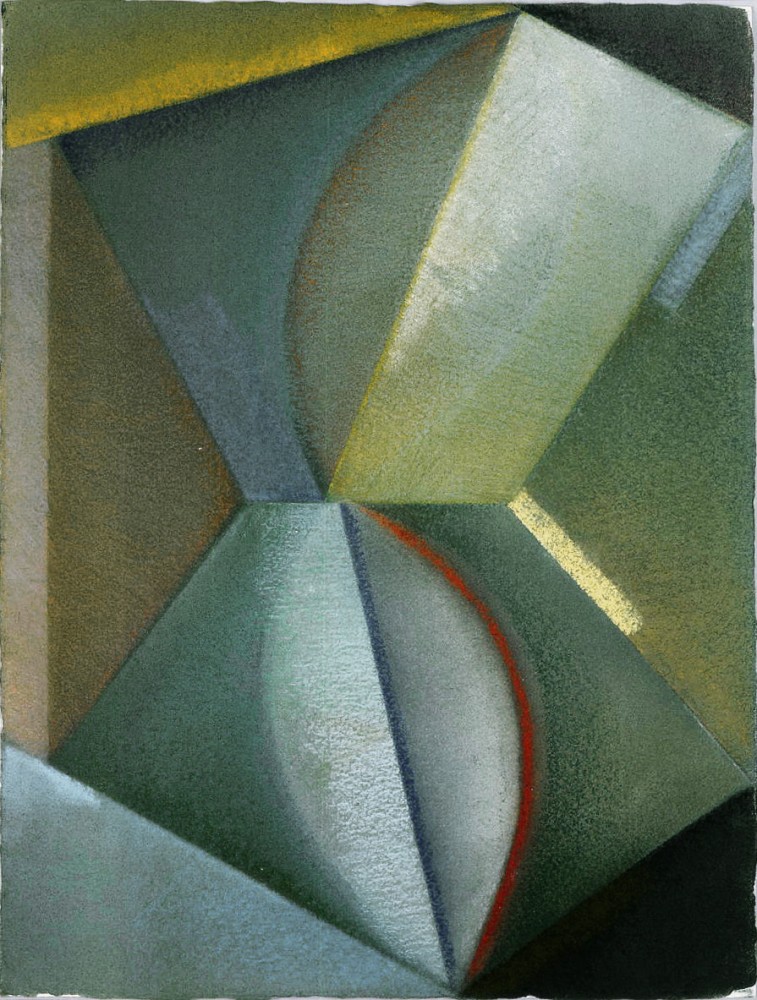

Umberto Riva, Specchio di narciso 5 (1994).

HUO: When referring to an artist’s catalogue raisonné, what is meant is a scholarly collection with progressive numbering; within it, it is the artist who decides which work marks the beginning of his or her own oeuvre. In your architectural catalogue raisonné, which project is number one?

UR: I never dated or signed any of my paintings, whereas in architecture a timeline is inevitable. The answer to your question is the Case di Palma, the summerhouses I built in Stintino, Sardinia (1970–72). You see, I didn’t use glass in that case. I used natural terracotta tiles that had been baked in small furnaces. I had part of them glazed in blue so that I could lay them with alternating blue/terracotta colors. Color is what saved that building because we didn’t get permission from the heritage-preservation office in Sassari to make a vaulted roof, and when the client asked me to insert some random openings, I opted for a continuous series of triangles.

HUO: Case di Palma, Casa Ferrario (Osmate, 1975), Casa Tabanelli (1972–74)… they are all very different works. In the 1960s, the widespread architectural paradigm included a tendency to make plans with broken lines, asymmetries, oblique angles, and disjointed surfaces. I wonder, then, what are the leitmotifs of your work?

UR: I’ve always explored the theme of instability, incompleteness, mistakes. Since my work was never based on certainties, I value the use of mistakes. Because nothing is a priori, I have no statement to make, but I try to find some fundamentals simply through practice — and also, in so doing, through chance.

-

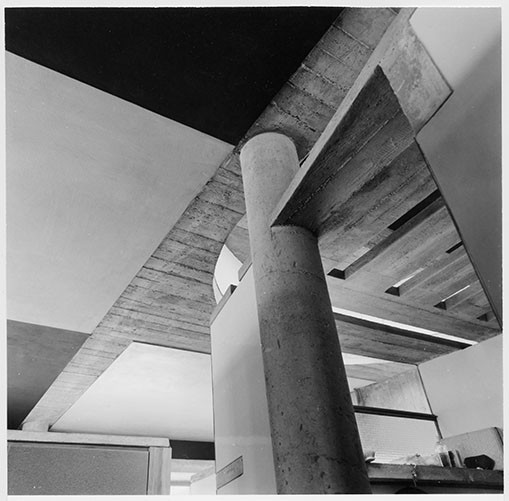

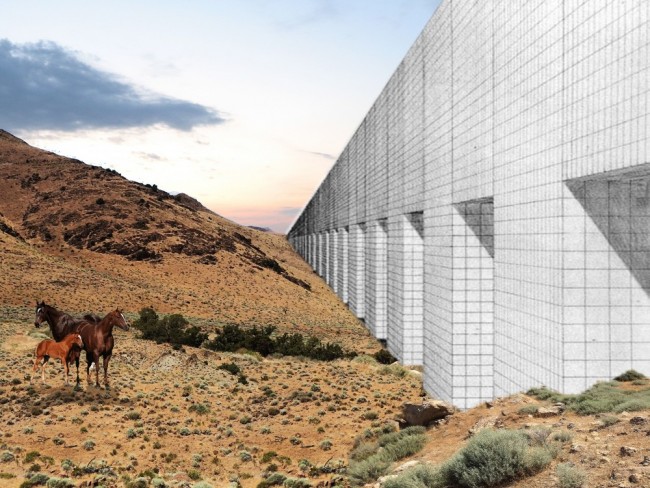

Casa Miggiano (1991-96); Otranto, Italy.

-

Casa Miggiano (1991-96); Otranto, Italy.

-

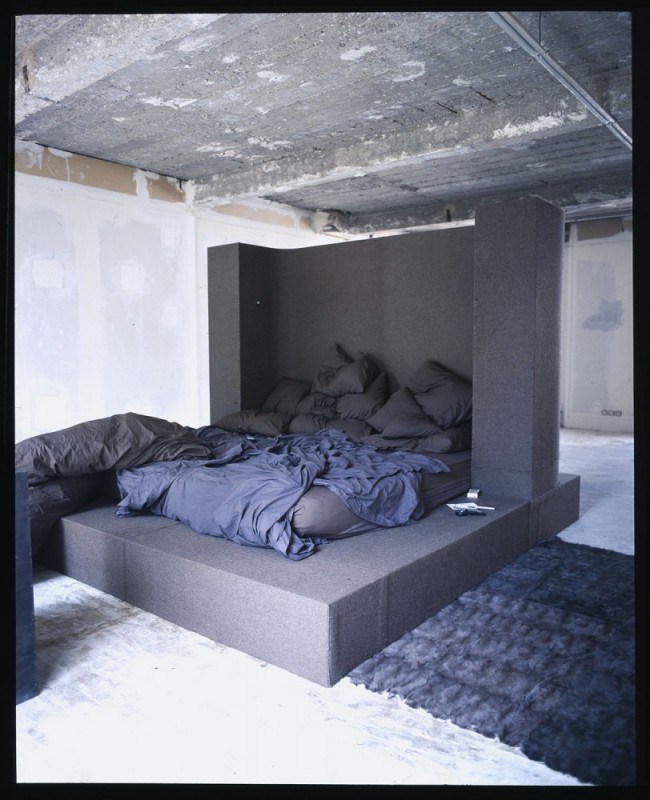

Casa Riva (1966–67); Milan, Italy.

-

Casa Riva (1966–67); Milan, Italy.

-

Casa Riva (1966–67); Milan, Italy.

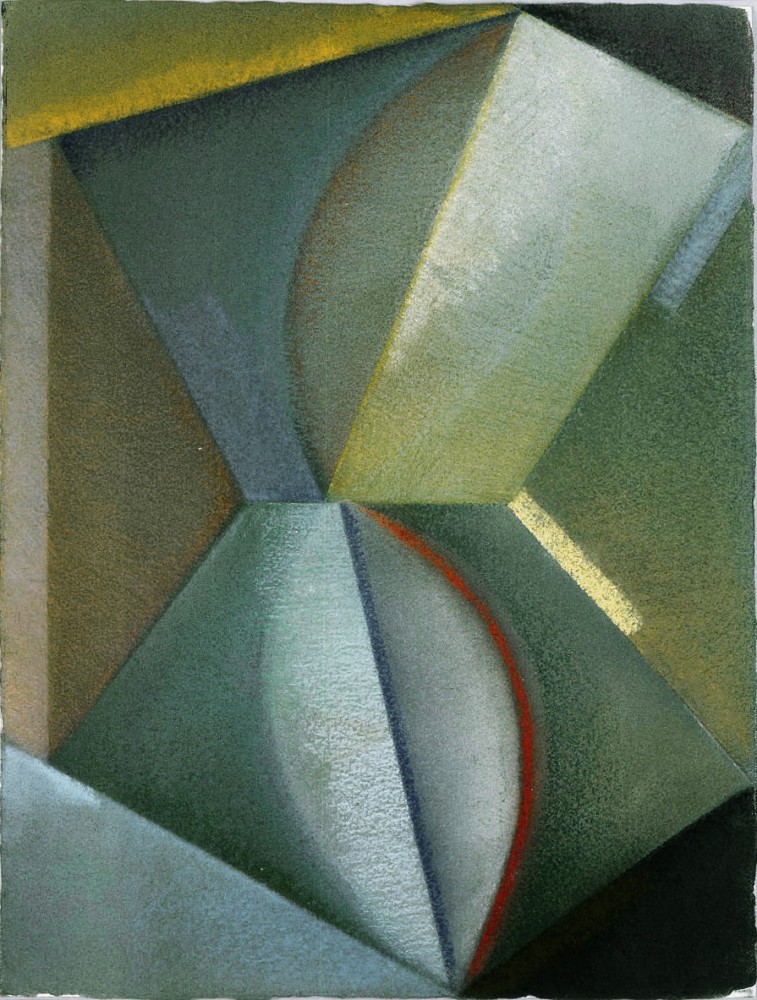

HUO: Your paintings are clearly abstract compositions. In this regard, Gabriele Neri’s book Umberto Riva: Interni e allestimenti (2017) claims that your houses and buildings are also abstract compositions because they have rhythm, music, light, color, and form, all of which, I quote, “juxtapose and integrate different levels.”

UR: I’ve always worked on plans and sections. If you compare the plan for the Casa Ferrario with some of the paintings I made about ten years later, you’ll find some common points. One can see in them the need not to leave anything unexplored because it is exactly from that gap that some form of salvation might emerge. This is why I try to find release from borders, making them as relevant as the center. When examining the whole design phase in my work, it’s clear how the plan shows a certain degree of formal autonomy as a visual product. This is a way to test its validity because there’s no such thing as an ugly plan leading to a beautiful building.

-

Umberto Riva, Pas de Deux 2 (1996).

-

Umberto Riva, Tentativi di fuga (1984–95).

-

Umberto Riva, Aquilone (Undated).

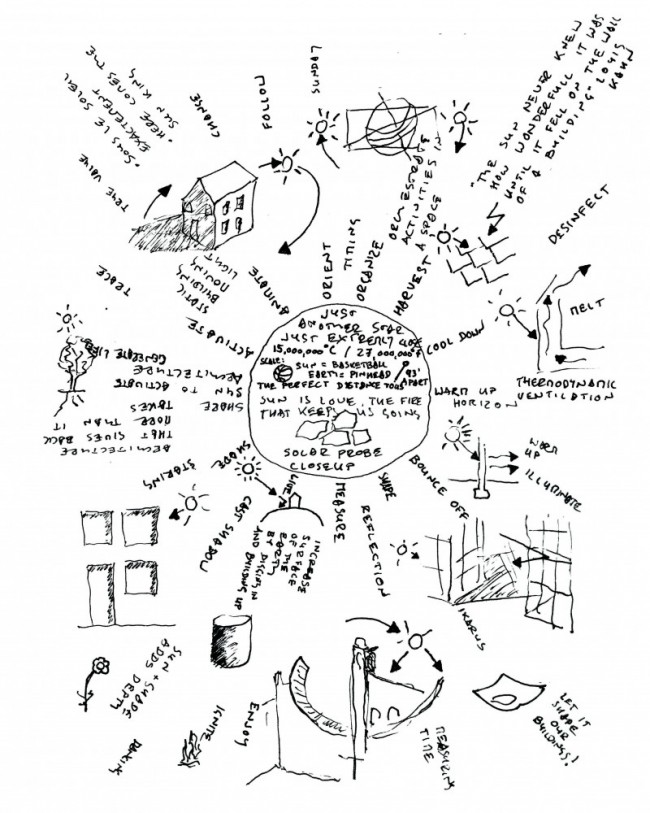

HUO: Nowadays drawing, which is at the heart of your work, is gradually fading away with the Internet. During my last conversation with Umberto Eco, he said, “I’m very angry because handwriting is disappearing. Architects only use computers and students in schools are no longer writing. It is the end of civilization.” In this respect, what role does drawing play in your work? Do you still make sketches?

UR: In the past, I used to lay out drawing, over drawing, over drawing. But now I’m completely stuck — I no longer work at the drawing board because I get tired a lot, I’m out of physical energy. Sometimes I get a collaborator to draw out projects on the board to which I then make revisions with a pencil. Since I don’t build models, this is my way of trying to give a sense of depth and shading to the drawing.

HUO: By the way, you’re almost 90 and still incredibly young. What’s your secret?

UR: The refrigerator. Freezing. Cryonics. (Laughs). You see, there are people who grow more intelligent as they age. I remember architect Ernesto Nathan Rogers, who I met while I was a student, telling me, “You’ll become intelligent when you’re 80.”

Casa De Paolini (1985); Milan, Italy. Photo by Francesco Radino.

HUO: Right now you’re working on a project in Otranto, Apulia (an extension to Casa Miggiano, built by Riva in 1991–96). Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown said that we could be “learning from Las Vegas,” while you say we could be “learning from Apulia,” making an explicit reference to its poverty, asceticism, and essentiality. One might say that Apulia is your Las Vegas.

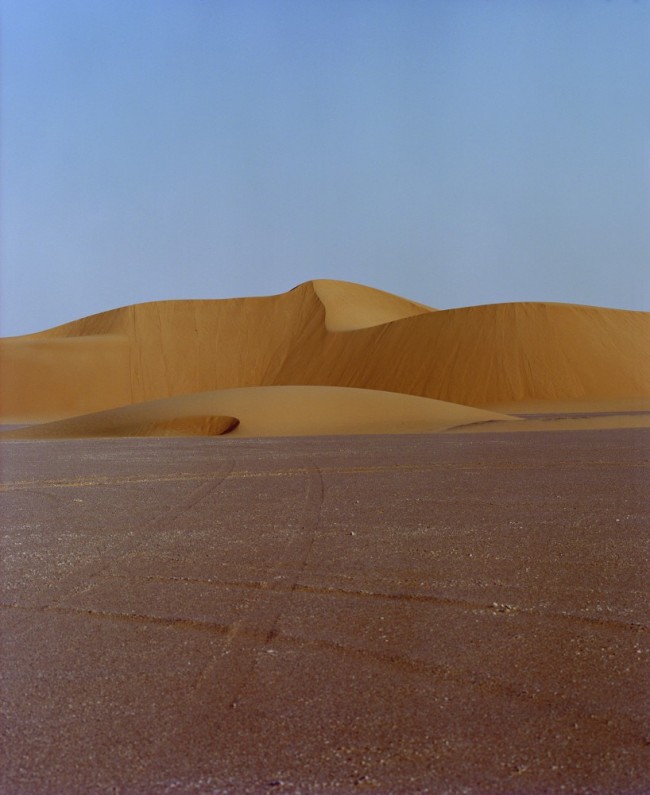

UR: Indeed, and before that came Sardinia. My father was Sardinian, and in some way I rediscovered in that island the reason of my origins, of a certain physicality and relationship with light. Over there, like in Apulia, buildings are always essential, waste is unheard of, there is no need for large openings. Light has such a powerful refracting quality that windows don’t have to be large, because what really matters is its refraction in space. Another key factor is volume, which translates into the need for low spaces. Old vaulted ceilings, often made for structural reasons, were usually high, but if one observes the ratio between these and the height of apertures, it is surprising to see how the smallest opening lets in an extraordinary amount of light, since there’s such a high degree of refraction.

HUO: The 1960s saw the Arte Povera movement — literally “poor art” — but in Apulia you’re talking about architettura povera — “poor architecture.”

UR: Vernacular architecture was literally poor, because there were no means to build otherwise. Glass was an expensive material, hence the smaller size of doors and windows, which coincidentally afforded residents a higher degree of protection. Many buildings in Apulia are basically little castles. Otranto, for example, was invaded by the Turks in the 15th century, which made defensive houses where people could foresee the threat of imminent attack all the more needed.

HUO: Tell me about your current work on Casa Miggiano.

UR: It concerns the revisiting of a pre-existing house that I made in the early 90s for a family with that name. Among their heirs, there is one of the daughters who needs her own living space but can’t afford to move elsewhere. So we’re working on an annex, which building regulations limit to a maximum footage of 860 square feet, and we’ll try to turn it into a way to draw in natural light. Working on a pre-existing space somehow facilitates my task because it allows me to maximize its drawbacks and turn them into potential. As you can see, the mistake is a recurring theme in my work, if mistake is meant as the illuminating key to solving a problem. One example of this is Casa Frea (Milan, 1983), where the mistake — in that case, the banality of the space — is neutralized by “breaking” the volumes open with the use of glass and mirrors.

Casa Insinga (1989); Milan, Italy. Photo by Francesco Radino.

HUO: A real masterpiece. Which, of all your buildings, is your favorite?

UR: The next one, the one that’s yet to come. (Laughs.) The consequence of making architecture the way I do, as an “artist” so to speak, is that there’s no final result. I always regard my works with suspicion and find it vital to think that further improvement will come in the future.

HUO: I quote from the article “Architetti d’Italia: Umberto Riva, l’anti-minimalista” (“Architects of Italy: Umberto Riva, the Anti-Minimalist”) published in the Italian magazine Artribune: “There are at least seven lessons one can learn from Umberto Riva’s non-method. First, in articulating a space, one must generate a plurality of functions in order to avoid the trap of aestheticism and formal arbitrariness. Complexity without a functional correspondence is, in fact, nonsense. Second, it is essential to consider furniture a vital element of architectural space, and it is therefore advisable to give plastic energy to its design.”

UR: Exactly. It is important not to preserve a vision as static, but allow it to suggest new visions that engage in a mutual and constant dialogue. In point of fact, during a lecture, I said that looking at one of my plans is like looking at a pinball table since neither lets you linger in one single spot. Actually, a plan’s banality is often changed through the use of furniture. What I mean is that furnishings help you disrupt the predictability of some spaces. For this reason, they are usually unique pieces that are hardly if ever conventional or replicable, their form instead, being determined by the function they play in that space, contributing to shaping it and making it what it is.

HUO: Speaking of furniture, can you tell us something about your next table project, commissioned by Nicoletta Fiorucci (founder of the Fiorucci Art Trust)?

UR: The sketch of the table that inspired the project is of an entirely wooden structure. The top resembles an ellipse, a circular shape squeezed at its sides, a quasi-circle. This is one of the things I learned from Scarpa: the contemplation of shapes that contain a mistake within them. The top, which is not really circular, finds in this flaw an exaltation of its circularity. The same can be said of a square whose sides are not all equal in size but show some minor deformation: it is no longer a square, but a rectangle by mistake. For this new project, I received some very specific requests such as bronze legs and a glass top. This implies that the initial leg must be fully reconsidered because it will have to hold up the crystal top, whereas, in my sketch, the top is an essential part of the four legs, acting as a shared element of conjunction. Instead, the use of glass makes it necessary to build legs that are structurally independent, as though they were self-standing micro-buildings, and then place the glass on top of them. It’s exactly everything I thought I’d never do.

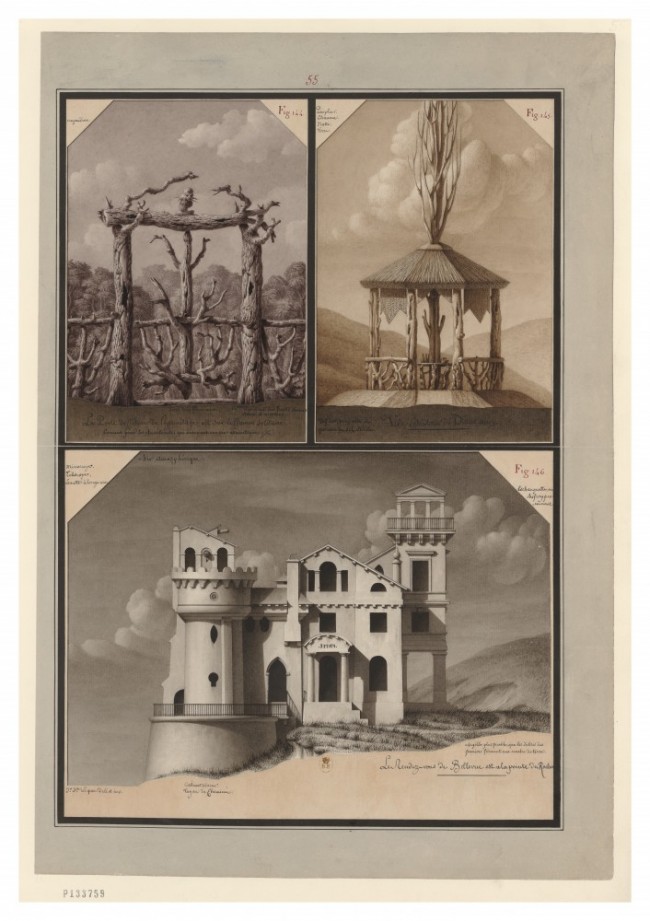

Tav 2 dining table (2018); Ash wood. Photograph by Omar Golli. Available through Giustini / Stagetti.

HUO: Architect Stefano Boeri, a common friend of ours, sent me a question for you. He wants to know about the house you designed for the Italian poet Vittorio Sereni, in Via Paravia in Milan.

UR: Back then, in the 70s, I had the privilege to get to know Sereni, and to approach other great poets such as Giovanni Raboni and Bartolo Cattafi through the director of a co-op who was looking for new members. As a result, I ended up designing an apartment for Sereni’s wife, Luisa. So, besides designing the whole building in Via Paravia, where I moved in too and took pleasure in painting the ceiling, I didn’t do much. In this building I chose not to use concrete as a Brutalist material because I preferred to give it a more humane outlook. I took in the lesson learned from Le Corbusier and Louis Kahn, whose Salk Institute I was lucky enough to visit during a trip to the United States. At the time it was like a leap of faith: I mean, I was unable to conceive of any material other than reinforced concrete that could better embody modern architecture. Sadly, one of its major downsides is that it’s impossible for it to age well: under the effects of weathering the rebars start to become exposed, and rather than acquiring a new patina with the passing of time, the material deteriorates, instead of “becoming.” This is why it’s very hard to restore.

HUO: Do you have a favorite project among those that were never realized?

UR: Unrealized projects — and luckily there aren’t many of them — have also been moments of heartbreak. The last one was for a pavilion at Expo 2015 in Milan. It consisted of a fiberglass-resin shell, a kind of undulating skin designed to light up at night like a Japanese lamp. Inside it was hollow, empty.

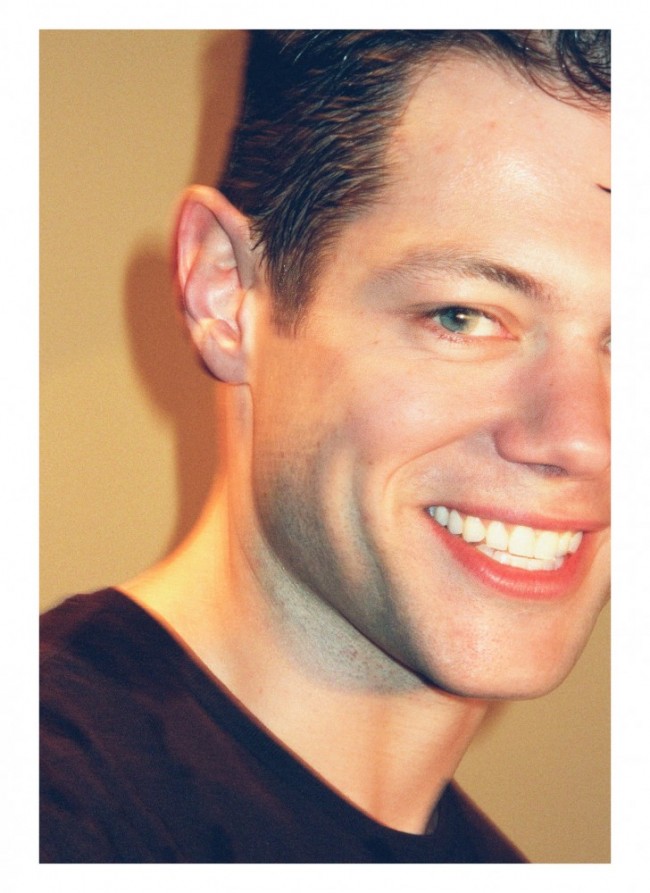

-

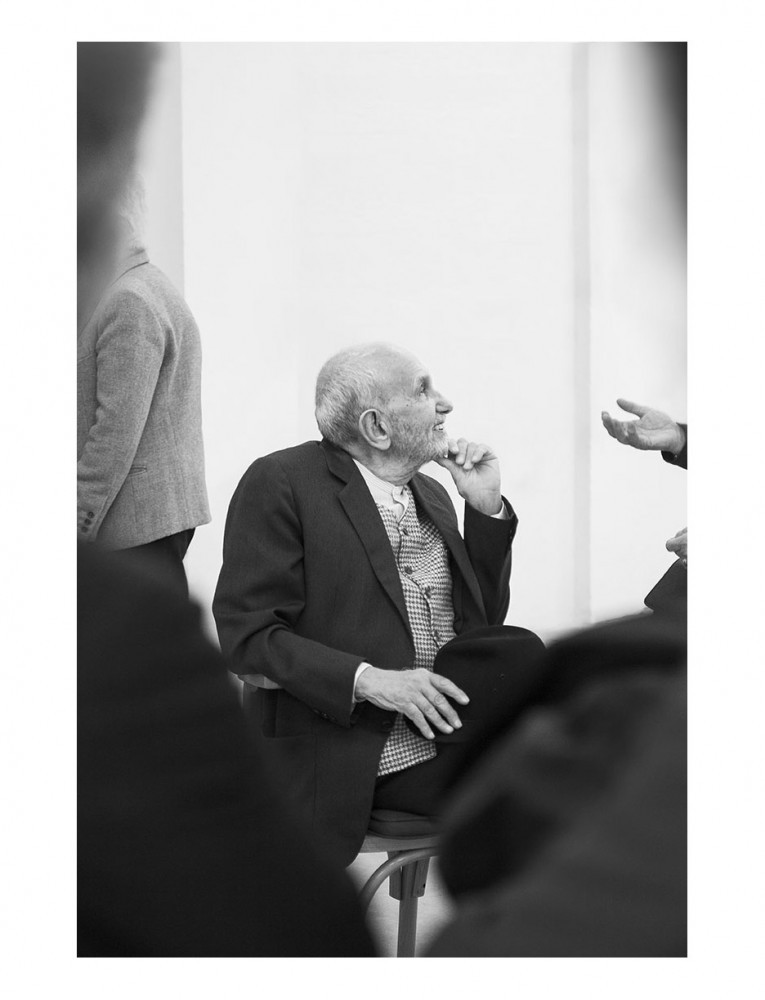

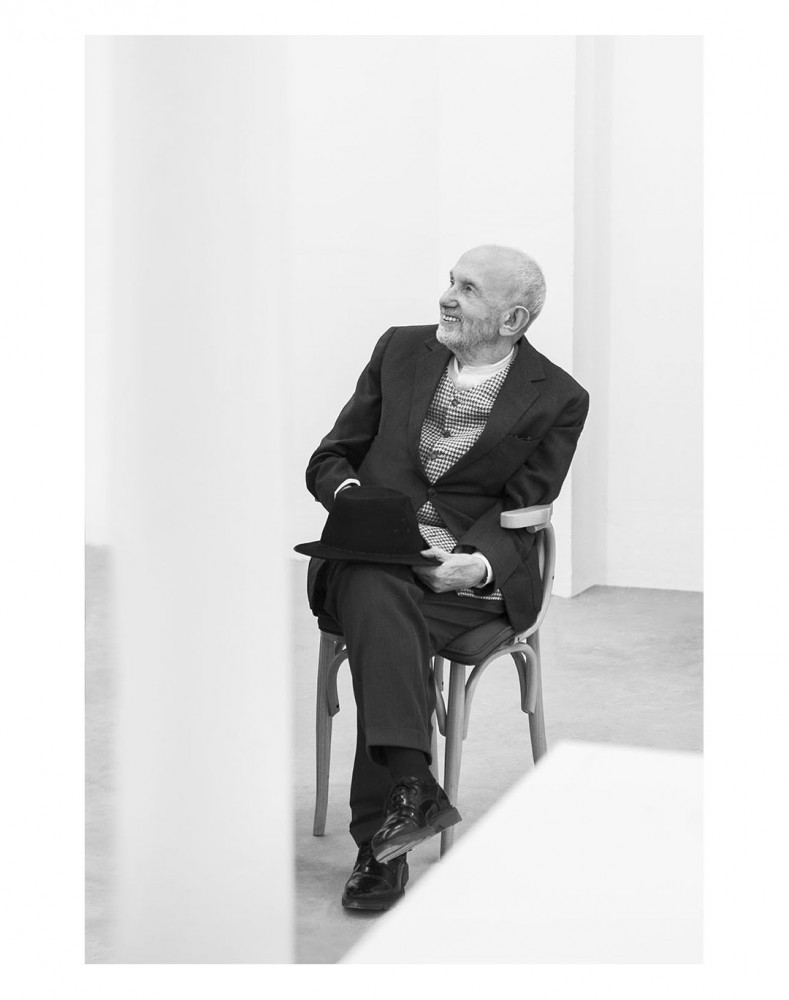

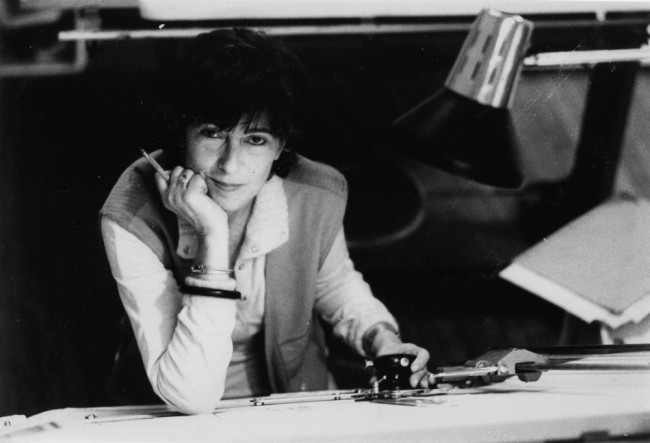

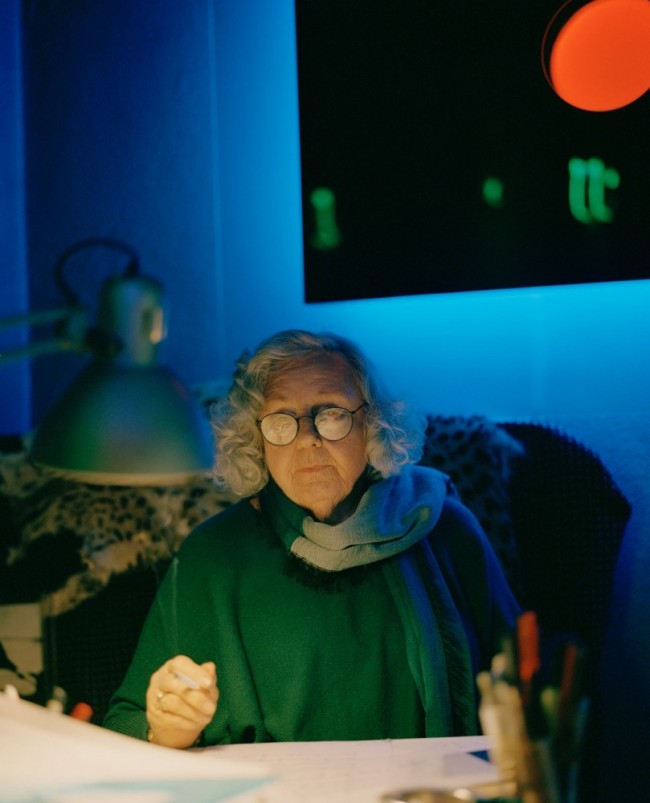

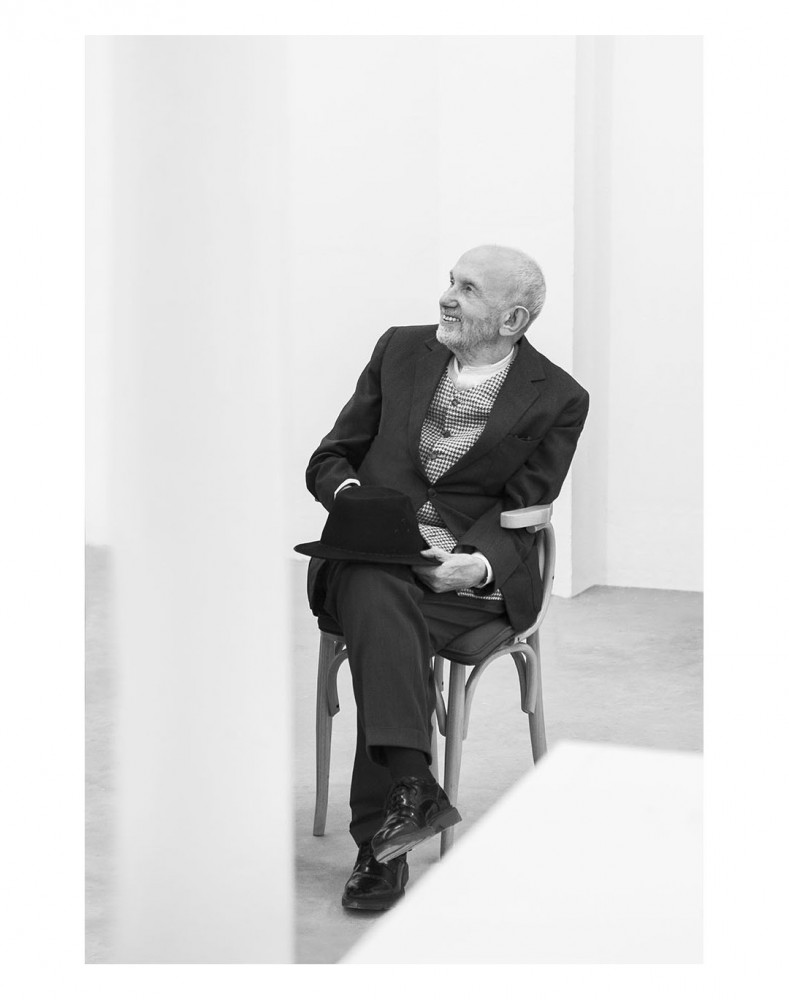

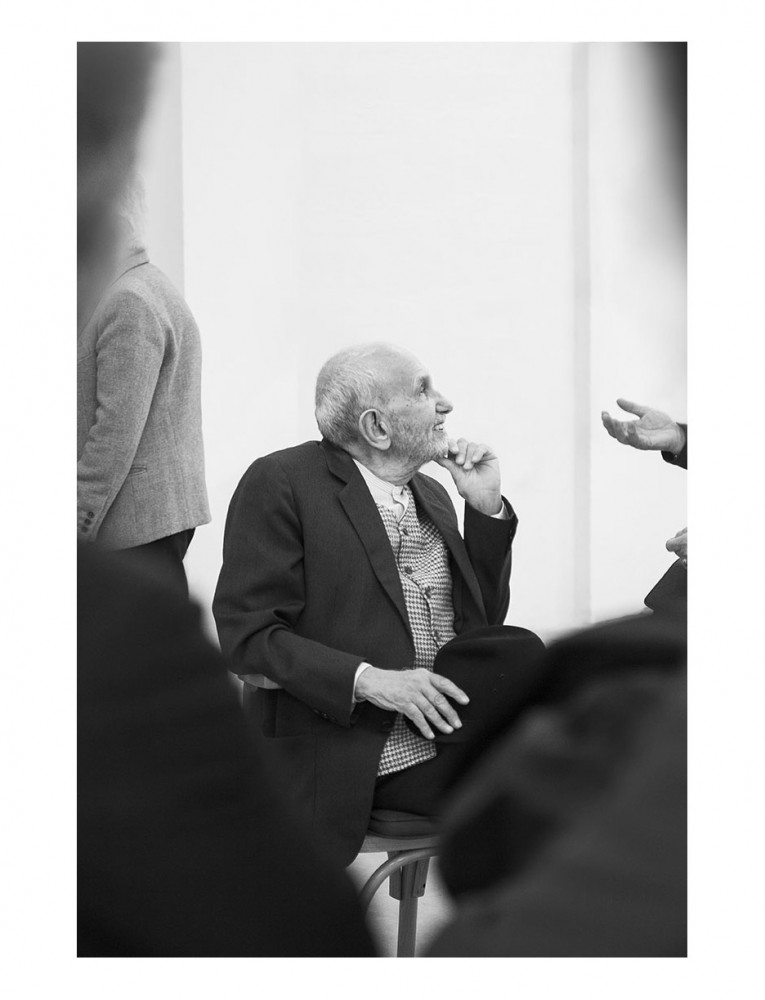

Portrait of Umberto Riva by Omar Golli.

-

Portrait of Umberto Riva by Omar Golli.

HUO: Going back to Rilke and his Letters to a Young Poet, what kind of advice would you give to a young architect today?

UR: This is really a huge responsibility. I think of Sigurd Lewerentz, an extraordinary architect I never really forgot about and have recently rediscovered, and I think even more of Gunnar Asplund. There is a certain degree of irony in the sagacity of these mentors, in how they worked with the teachings of the classics and then twisted them completely. I can mention as an example Asplund’s own summer house in Stennäs, Sweden, which is entirely built on the principle of architectural poverty. That work teaches a lesson — the complete absence of waste — which, in this case, is also the moral quality of architecture itself: never make more than what is necessary, never indulge in self-celebration, never make while thinking that you are making history. On the contrary, one makes architecture because it is a lifesaver that gives answers to the nonsense of living.

Translated from the Italian by Andrea Vesentini.

Text by Hans Ulrich Obrist.

Portraits by Omar Golli.

All images courtesy Umberto Riva.