INTERVIEW: New York Design Duo D’Aquino Monaco Tell All About 20 Years Of Teamwork

Carl D’Aquino and Francine Monaco have been in practice together for two decades. Both trained in architecture — although Carl rejected it for interior design — the pair have carved out an international reputation for designing lush modern spaces with subtle twists. While best known for their residential spaces, D’Aquino Monaco’s multidisciplinary portfolio spans resorts, hotels, spas, and corporate offices and has earned them lots of features in the press, as well as top industry accolades — both D’Aquino and Monaco were inducted into the Interior Design Hall of Fame more than a decade ago. And while they’ve designed beachy hospitality experiences like The Ritz Carlton, Grand Cayman — the resort’s futuristic Silver Rain Spa they also designed is especially dreamy — D’Aquino and Monaco are both dyed in the Jacquard wool New Yorkers. D’Aquino even grew up in Manhattan, though not in the condo high rises and uptown penthouses he now designs. PIN–UP caught up with the pair to talk about their humble origins, Mafia folklore, and the dynamic relationship that defines their practice.

-

A hallway detail at Upper East Side Townhouse, designed by D'Aquino Monaco. Photography by Stephen Kent Johnson.

-

Living room detail at Upper East Side Townhouse, designed by D'Aquino Monaco. Photography by Stephen Kent Johnson.

What are your respective backgrounds? Carl, you have more years of experience?

Carl D’Aquino: Yeah, I’m older so I have more experience.

I didn’t want to quite say it like that.

CD: I had hair when I started, okay? And I worked in architecture. I graduated architectural school, at The City University of New York. We were the second graduating class.

And you’re from New York City, as well?

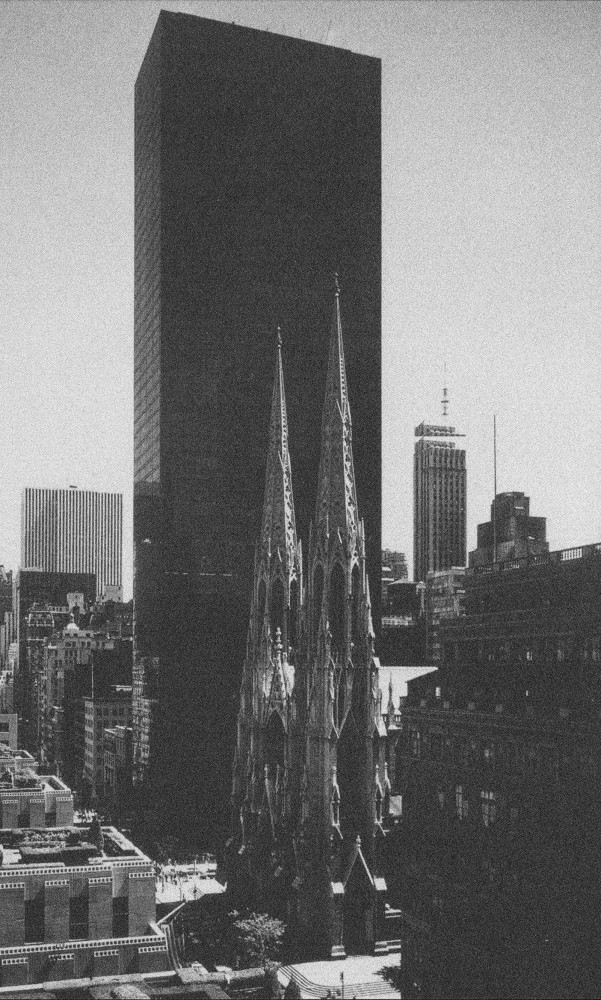

CD: I’m from Chinatown, the Alfred E. Smith housing projects. Chinatown and Little Italy were right there, and my mother and father’s families had immigrated to Henry Street. We grew up post-war babies. It was a very integrated housing project. And I have a very funny long story. Last year, I took my spouse, antique dealer Bernd Goeckler, and I wanted to go see St. Joseph's Church, which is being de-acquisitioned by the Roman Catholic Church. So we had dim sum and we went to St. Joseph's and Bernd goes, “Let’s see where you grew up.” So we cross and go into the projects. We go to 10 Catherine Slip, count up one, two, three, four, five, six, seven, I see those windows, those were my windows, that was my bedroom. A woman puts her face out of the window in the apartment next door and she goes, “Hello Carl.” Now I haven’t been there since I was born. I said, “Bernd, did you hear that?” And she goes, “Hello Carl.” My hair stood on end. This was really happening. And then I realized this woman next door has never left, apparently, and she was talking to my father. I look like my father.

Francine Monaco: You look exactly like your father.

CD: She was talking to my father. I couldn’t — I mean I was shaking. It was so odd. And we didn’t go in. I didn’t want him to go in and see what the projects are really like because they’re really tough places.

FM: I think it’s really sweet that this woman not only recognized you, but how often do you maybe see somebody that you kind of recognize and you really call out to them after so many years?

CD: It was astounding.

Yeah, that’s incredible. Maybe they had an affair.

CD: You never know. My father was quite —

FM: Because she was very positive.

CD: You never know. (Laughs.)

-

The kitchen at D'Aquino Monaco's recent Central Park South project.

-

The living room at D'Aquino Monaco's recent Central Park South project. Photography by Stephen Kent Johnson.

-

Detail of the living room at D'Aquino Monaco's recent Central Park South project. Photography by Stephen Kent Johnson.

-

Kitchen and dining room at D'Aquino Monaco's recent Central Park South project. Photography by Stephen Kent Johnson.

You later went to City College?

Yes, on 137th Street. It was the second graduating class. It was exciting. It was a new school of architecture. They didn’t even have the building ready yet, and the school was in this rented garage space then. It was fabulous. We had all these great teachers.

But you eventually went on your own?

CD: I worked for at least ten years in architecture and then I left it. I had some incredibly bad experiences, but I had a good experience which was with the late Giovanni Passanella who was a gentleman architect. It was a wonderful, wonderful opportunity, as was my experience with Alan Buchsbaum

What is a gentleman architect?

FM: It’s a very good question these days.

CD: He knew how to live a life. He knew Fellini and the other one who was the Mafia priest in the Bronx whose brother was the guy who walked around in a bathrobe on McDougal Street. Was it Gigante? No. I forgot his name. They were two Mafia brothers.

FM: One of the Mafia bosses that’s famous for, pretending actually, to be delusional. He’d walk around the streets in a bathrobe because he was always trying to escape conviction by being a little less than all there.

CD: Meanwhile his brother was a Franciscan priest in the Bronx getting housing for the poor — working with UDC and really developing low income housing on a big scale. And our office was in Carnegie Hall. We had a sound stage, and I used to bike up from Thompson Street, which is where my apartment was, have lunch on the balcony, listen to an orchestra rehearsing in the main hall, and the place was full of ballerinas walking through. It was so artistic and so exciting.

Wow. On 57th?

CD: Yeah. In Carnegie Hall itself. And then I had some pretty frustrating experiences after that, which made me leave architecture and I worked for a decorator for a few years and took on private projects, to pay for my therapy.

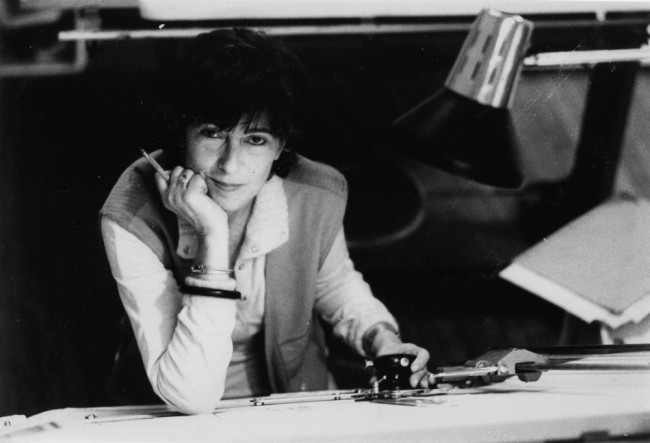

Carl D’Aquino and Francine Monaco. Photography by Josep Fonti

Francine, where did you get your start?

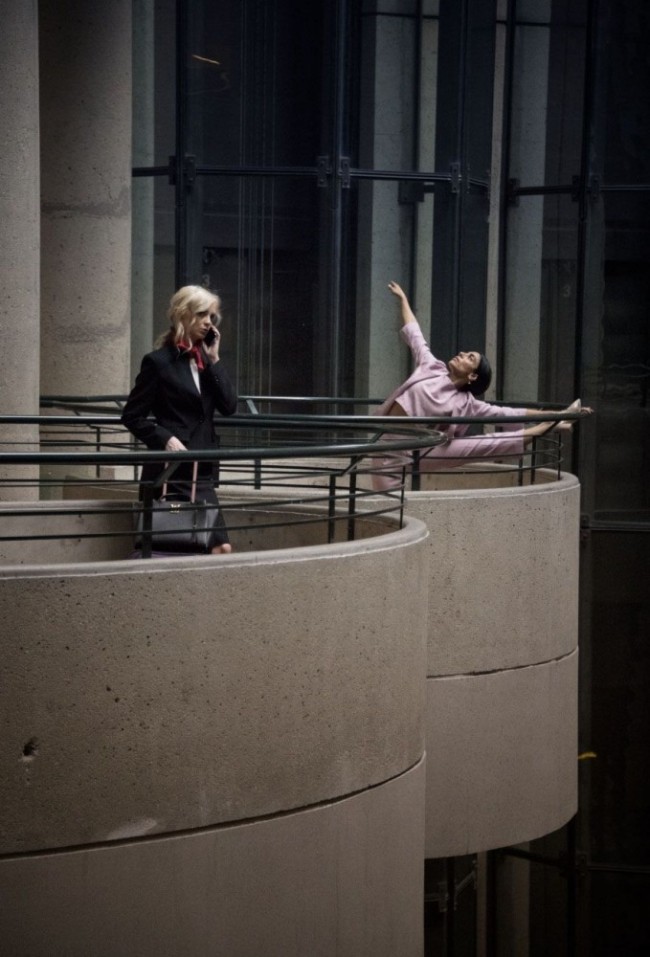

FM: I went to architecture school at University of Cincinnati. After that I went to work for a firm that did high-end residential work. I really got thrown in the deep end of the pool, working on houses, big townhouses out east, and that was really where I got a real understanding of what it means to do residential architecture, of how you create a lifestyle within the architecture of a house, how you deal with the decorative end, and the design end, and how the two can and cannot fit together well. And then from there, I actually went to work for the Guggenheim, and I was part of the Guggenheim planning department when they were expanding the building uptown, and putting in the SoHo Guggenheim. I was involved in designing the office spaces that were part of the expansion. While I was doing that, the planning department had our offices in the Guggenheim. This was the best part of the whole thing. While they were working on the building, we took a little corner of it, set up our own planning office, and we had full reign of the building once the construction stopped. So we would get to wander around the rotunda because they had built the scaffolding all the way up to the skylight and we got to go all the way up on the scaffolding, look at the skylight, and go out on the roof. Every inch of that building was our playground. And then once that opened then I started getting work on my own and I was sort of looking for office space. That’s when I took a desk at Carl’s office.

Have you developed together a sort of style that neither of you had before?

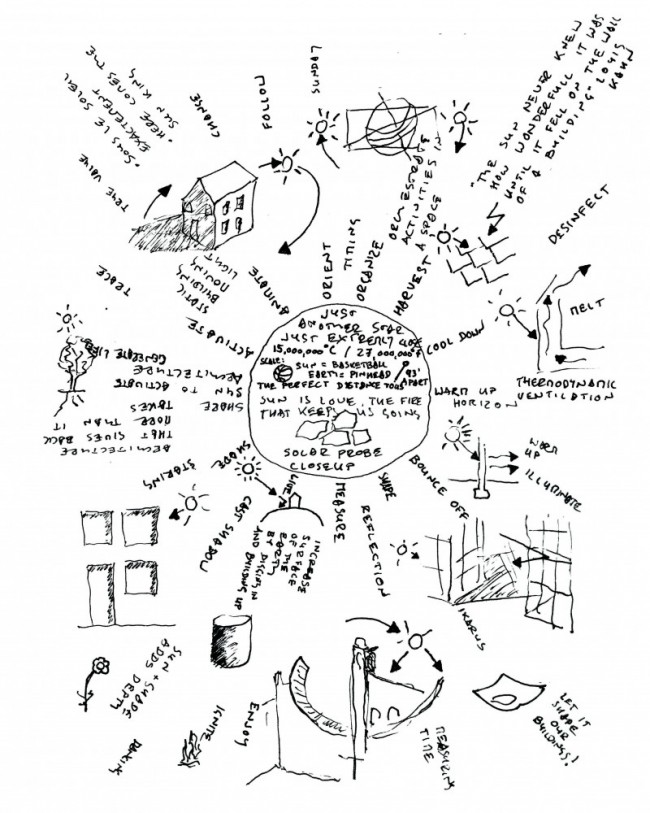

CD: Absolutely. FM: Definitely. The dividing line between what is decorative and what is architectural is very hard to find. And people are always asking like, “Well, who did that? Did you do that? Did Carl do that?” We don’t think there is a line, and the whole effort since we partnered was to figure out how blurry can we make that line so that the dialog between the container and the contained really starts to resonate in a way that it never did before. I think that the reason we came together to begin with was, as Carl kind of mentioned, that yes, I had an awareness of the decorative, enough to realize the role that it could play. My full awareness of the potential of it wasn’t there, and has only grown since we started working together. Carl approaches a project in a very different way than I do. Carl very much approaches it by thinking about how we move and how we fit in space. How do we occupy things? How do we place the furniture? How does that furniture create an opportunity for using those spaces? Whereas I definitely start from the idea of what is the scale? What is the size? What is the volume? What is the proportion of the space and how do those proportions create a kind of hierarchy and sequence of events as you move through? So these two lines of thinking when they really fit and are in dialog with each other, it’s just magical because then you really have furniture, decorative elements, and materials that are actually speaking to the scale, proportion, and the attitude that you’re trying to create with the architecture.

CD: It’s like trying to cook together.

FM: I mean we do disagree a bit.

CD: Oh, we disagree all the time. We’ve always disagreed.

FM: Yeah, you definitely disagree.

CD: I’m usually negatively based. (Laughs.)

Entrance hall of Tall Timber Farm in New York’s Hudson River Valley, the personal home of Carl D'Aquino and his partner Bernd Goeckler. Photography by Björn Wallander.

After 20 years of working together, do you already know where the red flags are?

FM: I think our process has evolved in a way because, as Carl was just saying, he’s very negatively based, so his response to something that’s presented is going to be, “No.”

CD: That’s really true. It’s terrible.

FM: So we’ve kind of gotten to the point where I know how far I need to take something before I actually talk to Carl about it because I don’t really need to hear “no” in the beginning. I just wait until it goes far enough so that I can see how far I can take it.

CD: For example, I didn't want my country house. My spouse and I fought over it. I didn't want to move to this house. Although it wasn't the first house...

FM: No, it wasn't. You said “no” to the first one.

CD: And rightly so.

FM: But then the broker had another house. He said, “Well, I can take you by this other house and see what you think of it.” And we go by the other house and we get out of the car, we go in, and he’s like, “Maybe this one?” But it wasn’t like a really firm yes. And I said, “I think this is great.” It was this house in Goshen, New York. When Carl and his partner Bernd (Goeeckler) went up to see it, they came back after the weekend and Bernd calls me independently — he didn’t want Carl to know — and says, “I want you to see something. We’ll send you some photographs.” And he sends me photographs of this house and it was this beautiful Georgian house on a hill. It fit Bernd because it’s this very American stately kind of place, and if you have met Bernd, he’s a stately gentleman. And I’m like, “This is really great.” I didn’t even know they were interested in buying a house. He said, “I think I want to buy it. But I want you to come see it. Can you come tomorrow? And don’t tell Carl.” And so I go up and I see it with Bernd. I tell him, “it’s a great house. I think it’s fantastic.” I said, “But it needs a lot of work. You’re going to have to probably spend this much money.” And then we get back and we talk to Carl. Carl’s like, “We’re not buying this. This is just, no. We can’t have this.” He's like, “No, no, no. I don’t want to live in the country. I don’t like this. There’s no train station. There’s no bus.” And finally it didn’t matter. Bernd was like, “I think it’s perfect. I’m getting it.” (Laughs)

CD: My big grown-up moment came after we turned it down. I was hoping for something more modern, and Bernd wanted something very American — he’s Swiss German. I realized having this house would really make him happy, and what did that matter what it looked like, what the style was? It was a revelation. I woke up and said, “Yes, let’s do it.” This would make Bernd genuinely happy. It’s something he really wants. And in the end, I love my house in the country, and Fran salvaged our marriage by being the architect for us. Otherwise I’d still be choosing a doorknob.

FM: Well, you really salvaged your marriage by not being involved. (Laughs)

Interview by Felix Burrichter.

Portraits by Josep Fonti. All other images courtesy of D'Aquino Monaco.