INTERVIEW: Artist Ilana Harris-Babou On Power Dynamics Of Domestic Aspirations

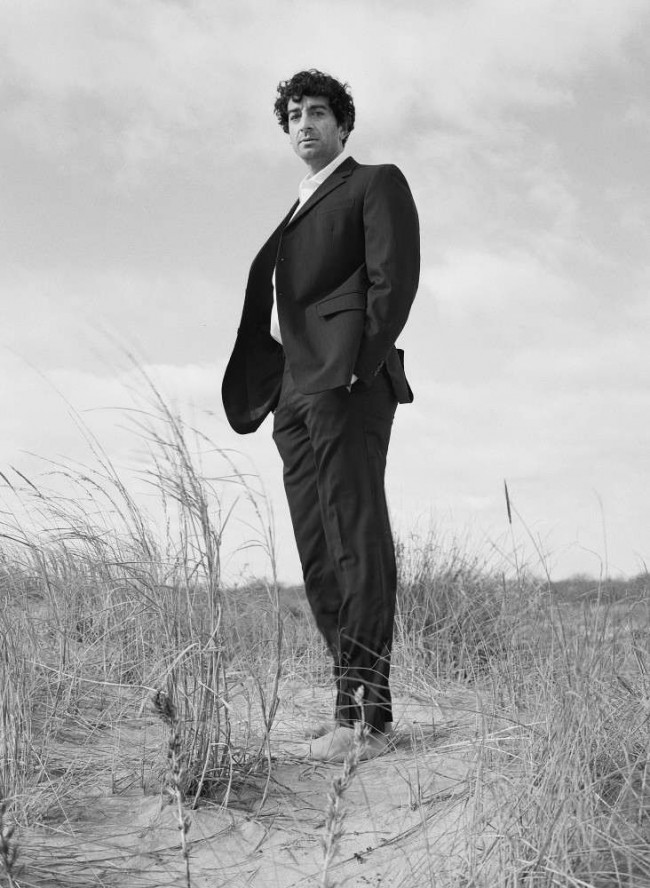

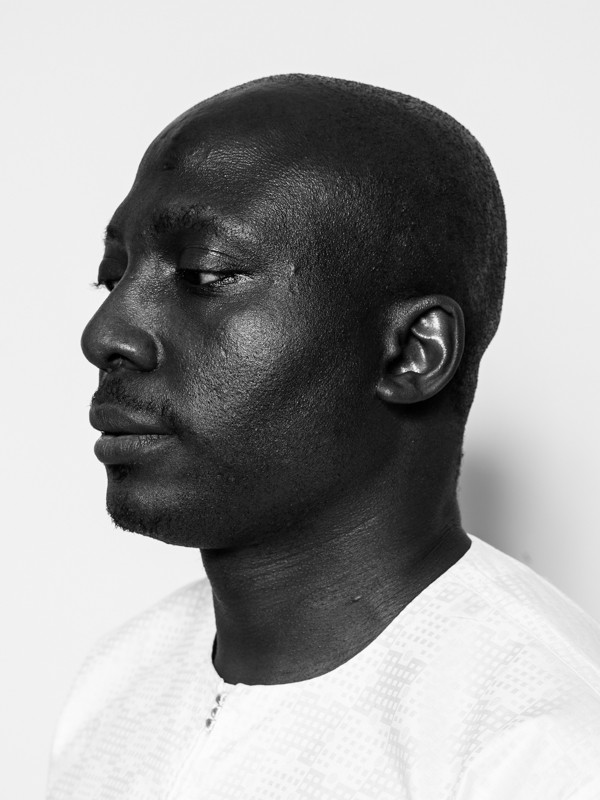

Artist Ilana Harris-Babou photographed by WangShui for PIN–UP.

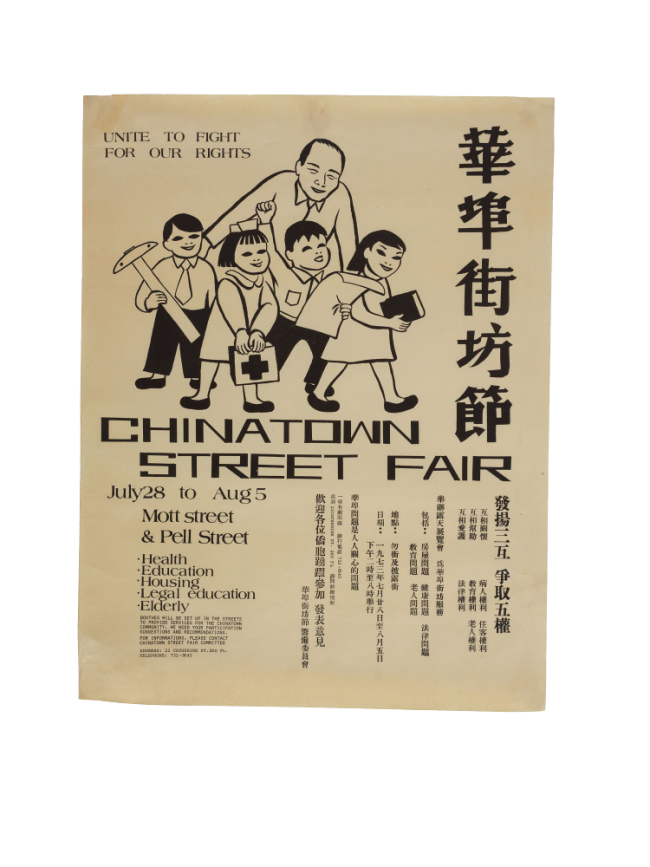

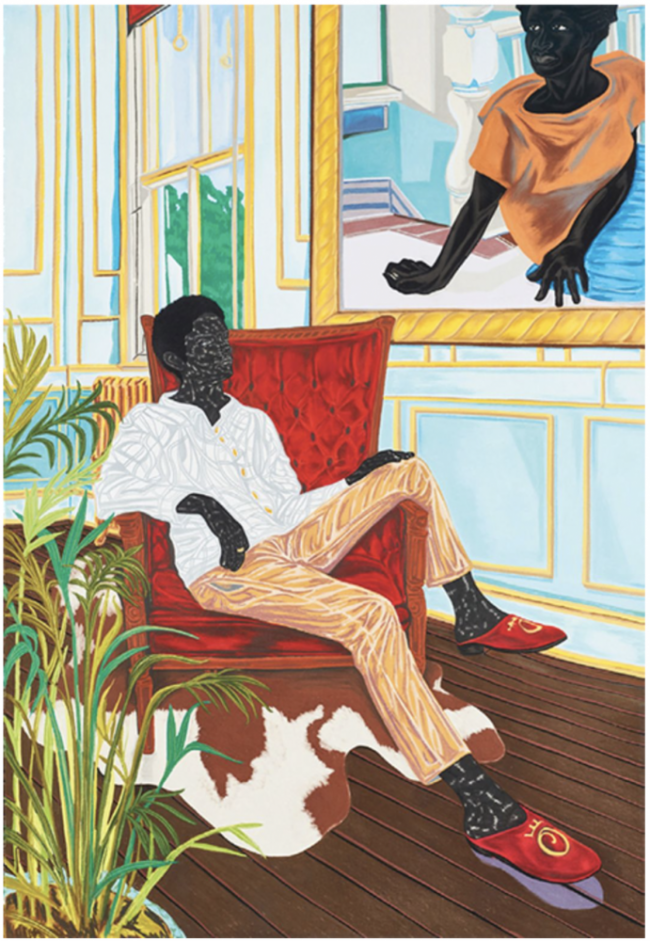

“Design without ties to its origin, history, or culture is like a tree without roots,” pontificates New York-based artist Ilana Harris-Babou, playing the role of a fictional home-furnishings-company CEO in Human Design (2019), one of three videos she showed at the recent Whitney Biennial. In these works, Harris-Babou interrogates the relationship between material culture, race, and authenticity with her trademark sense of humor — the same destabilizing wit that drove 2016’s breakout Cooking with the Erotic, her delirious take on the cooking show, sometimes featuring her mom. With her twisting of popular aspirational-media formats, Harris-Babou attacks serious issues such as reparations and redlining with sardonic savvy. Her 2018 exhibition Reparation Hardware, for example, transformed New York gallery Larrie into a high-end furniture showroom, as though the suburban stalwart Restoration Hardware had rebranded, its new name referencing the idea of financial compensation for the descendants of slaves. The show’s videos and ceramic sculptures looked to advertising, antique refurbishing, and home improvement to comment on the ongoing project of shaping our own identities. For PIN–UP, Harris-Babou sat down with fellow millennial wunderkind and Yale grad Jeremy O. Harris, author of Slave Play and Daddy, who’s recently shook up the New York theater scene. The two artists share an interest in unpacking aspirational material culture and the complex relationships between class, race, and labor. Appropriately enough, they met at the Meatpacking District’s Restoration Hardware store, a stone’s throw from the Whitney, where they discussed mothers, reparation, and provenance in the context of fantasizing a resolved past.

Jeremy O. Harris: There’s something about the way your work engages with social media that makes it feel like it’s reaching an audience in whatever subconscious space we’re all on when we’re scrolling through Instagram.

Ilana Harris-Babou: Yeah, that’s real. I think I started using Instagram maybe later than others and my first foray into it was a fake food blog. I would take the name of a famous cooking show host and add “official” to the end, posting pictures of things like a rock with jam on it — things that were photographed beautifully and that at first glance you might think were real, before realizing they’re either grotesque or illogical or both. I would try to grab people who thought they were following the real accounts. At first I called the account @melissa_clark_official, after The New York Times food lady, because I was obsessed with her. She’s just this cheery Park Slope mom, and there’s something really interesting about that kind of a person to me — an identity that is polite polite. She cooks food from all over the world and she wants her daughter to be a feminist and has this bookcase behind her. She’s quote-unquote progressive, but still inhabiting this space of perfection.

-

Ilana Harris-Babou, Cooking Erotic (2016): video still.

-

Ilana Harris-Babou, Cooking Erotic (2016): video still.

-

Ilana Harris-Babou, Cooking Erotic (2016): video still.

-

Ilana Harris-Babou, Cooking Erotic (2016): video still.

-

Ilana Harris-Babou, Cooking Erotic (2016): video still.

-

Ilana Harris-Babou, Cooking Erotic (2016): video still.

There’s a matrilineal theme that’s really interesting — you frequently discuss mothers and daughters. What’s your relationship with your mom?

She calls me maybe five times a day. It usually goes to voicemail three of the five times. When I started working with her in my videos, it was because she was the closest person to being me that wasn’t me. And I definitely didn’t have the capacity to direct another person or hire an actor. Maybe it’s because we’re always playing a different version of ourselves that moms and daughters are really interesting — it’s this line of creation that just keeps going.

There’s something about work made by people who are momma’s boys or girls that for me always feels so rich in history. Especially in the black community, where mothers become the orators or the holders of history. I’m speaking in broad terms, but I feel it’s true in some of my own personal experience. I wonder what sort of history she imparted to you as a young girl in Brooklyn.

A whole lot of stuff — I even learned the bougie habits of fancy New York people from her. She basically grew up in this mansion in Connecticut — because my grandma was the maid and she shared a room with my grandma in this house — and on the Upper East Side. And so she was always inside these people’s homes, playing around with their stuff, watching their world and their life, and maybe seeing how funny and ridiculous it was. She doesn’t cook at all! The only thing she did in the kitchen was this fake Julia Child performance for herself in front of the mirror. “Save the liver!” she’d cry in a Julia Child voice. And maybe she’d make some canned Vienna sausage or something.

I love that.

When she was in early adulthood she lived in the Red Hook projects, and she’s talked about how the Brooklyn Queens Expressway felt like this really big dividing line that no one ever crossed into the rest of the world. She’d say crossing over that line and what was on the other side felt like it was almost a calling for her, but she also knew that folks looked at her side-eyed.

-

Ilana Harris-Babou, Cooking Erotic (2016): video still.

-

Ilana Harris-Babou, Cooking Erotic (2016): video still.

-

Ilana Harris-Babou, Cooking Erotic (2016): video still.

-

Ilana Harris-Babou, Cooking Erotic (2016): video still.

I feel that sense of the side-eye is this thing that’s related to class, and class ascension, and a sort of disregard for the facts of labor. Invisibilized labor seems to be at the core of much of your video work. You look at how today, in relation to black everyday existence, that labor has been glossed up and rarefied as an aspiration of the white and the wealthy.

I was making paintings and I started working with video because there was this one moment in the life of a painting I was really into, when it was still in a state of becoming while I was working on it. I thought, “Iʼll just put the camera on that moment and let people see it.” One of the professors was like, “Oh, you know all these 70s male performance artists have done that already. But I see your body in this. What’s that about? Explain that.” The expectation that I needed to explain myself as a person in the studio just relishing materials — that really pissed me off at that moment. So I started thinking about how these spaces of creation are similar to or different from one another: the genius Ab-Ex painter flinging around paints in a studio, or my grandma making pigs’ feet in the kitchen, or the soundstage kitchen, or the home improvement toolshed man-cave space. Just how all of these are similar to or different from one another and what kinds of labor are rarefied and what is mundane, and seeing what can happen when I mix those things up.

I want to ask you about this quote that I really love, and hear you navigate what it means for you: “The restoration of old furniture takes something stale and makes it sleek. The reparation of lost wealth takes the smooth, seamless inevitability of the American dream and makes it rusty.”

Reparations are so terrifying for so many people because they definitively name the past as not resolved. And as a failure — and not only as a failure, but a failure in economic terms specifically. I was thinking a lot about provenance, wanting to know where your furniture comes from, as though knowing where it comes from makes the place that it came from good or resolved. There’s a moralizing of provenance, origin, and history to feel okay with it. Reparation Hardware was at first just a play on words. Why do reparations generate so much fear? I mean now, since I made the piece, we have more people literally on the debate stage talking about reparations than ever — that wasn’t necessarily happening when I was first thinking about the piece, during the last (presidential) election, when the nefarious nature of nostalgia was all around us, screaming in our ears.

Artist Ilana Harris-Babou photographed by WangShui for PIN–UP.

We have one candidate who has stated that reparations could never get passed but that they could get free college for everyone, and we have another person on stage, who a lot of people think is a joke, saying, “Iʼve come up with the exact number that people should be given back. The black community should be given reparations, they deserve an apology, here’s the figure.”

The fact of being a black person in America often means not knowing your history.

Exactly. I can assume because I’m from Virginia that I’m a descendant of slaves, but I’ve never seen a family tree. You’re an artist who works in conceptual spaces a lot — what’s your conceptual reparation plan?

The program for reparations could be a kind of a code that you put into the computer and the computer would endlessly run and never have an output. I really donʼt know, and it’s that space of not knowing that I feel we need to acknowledge. Something’s wrong. It’s happening in our flesh and outside of our flesh, because it’s fleshy, like we can’t really quantify it. Sometimes I just wake up and I’m like, “Fuck, I’ve got all this shit, all this trauma, I feel it in my body.” And I think about all the people that got me to this place where I can have this comfy foam mattress I ordered online. I made Reparation Hardware because I felt I couldn’t find the answer.

I think a lot about our flesh in relationship to questions about reparations and slavery, and how the fact of our flesh and of our history both gives us different inputs and outputs for pleasure, but can sometimes make pleasure unattainable for our flesh and our bodies. I wonder if some of those questions around flesh and pleasure are why, in this new video for the Whitney, Human Design, you decided to go out into nature, because that’s the most primal space for pleasure and flesh to intersect. It’s almost more primal than the fact of labor — it’s the fact of wandering.

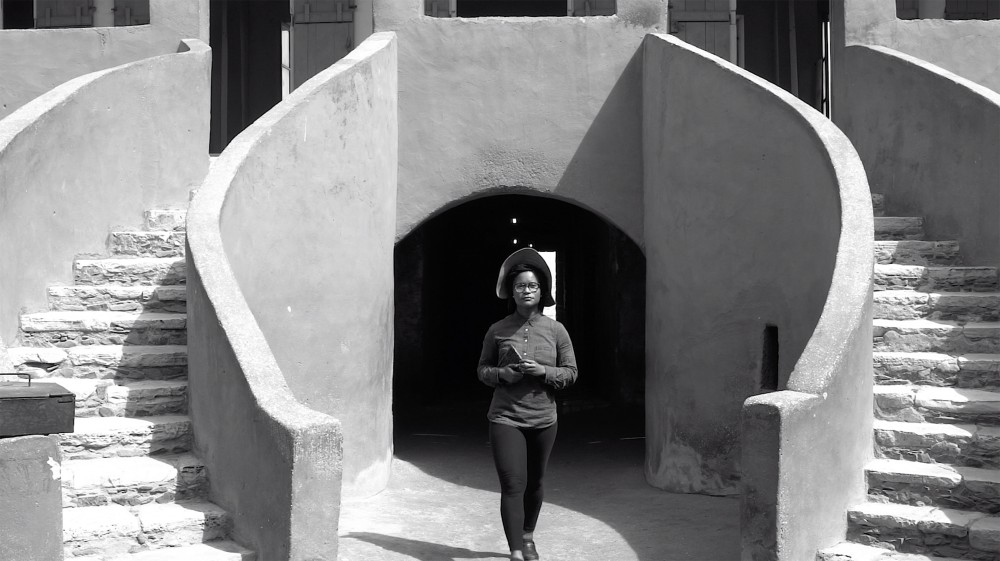

I was once again thinking about this idea of origin or provenance, and how we ascribe it to people and also to things. A lot of the video’s soundtrack is the soundtrack from Roots, the 1970s miniseries. I was thinking about stuff that’s complicated for me in terms of how we imagine Africa in the past, when it’s also a dynamic and evolving continent. So I went to a place called the House of Slaves on Gorée Island in Senegal. My father is Senegalese, and there’s a big history of African Americans going to Senegal to “go home.” That frames that space as a space of nostalgia when there are also real people living there in real time. I was interested in how the photos I’d seen of the House of Slaves were black and white — I think there’s even one by Carrie Mae Weems, at any rate she certainly went there — and then, when you arrive, it’s a super-cheery colorful space — salmon pink with aqua blue, yellow window blinds, and palm trees. So I was like, “Why, when we go back there, do we want to make it black and white, naming it a space of sorrow and not one of leisure?” Today it’s a vacation destination! And it wasn’t even a place where black people literally stepped out of a door and got onto slave ships — it was probably a rich slave trader’s house. Enslaved people definitely lived there, but we’ve created this really clear story about what that building is. There’s a door facing out onto the ocean that they call the Door of No Return. And Obama or Bush or the Pope would pose there and talk about how slavery was terrible, with Bush talking about it as though it’s terrible but resolved, and Obama at least admitting there are some ongoing effects. So when I got there, I walked up to the Door of No Return, and I was going to film myself kind of popping out of it, and I fell and sprained my ankle — the very first shoot! So while working on post-production I spent a lot of time trying to edit out the fact that I was limping. My ankle still hasn’t completely healed and might be wonky and messed up forever. And I think that’s really interesting — when I did that my ancestors were like, “We did not do that for you to do this.” (Laughs.)

-

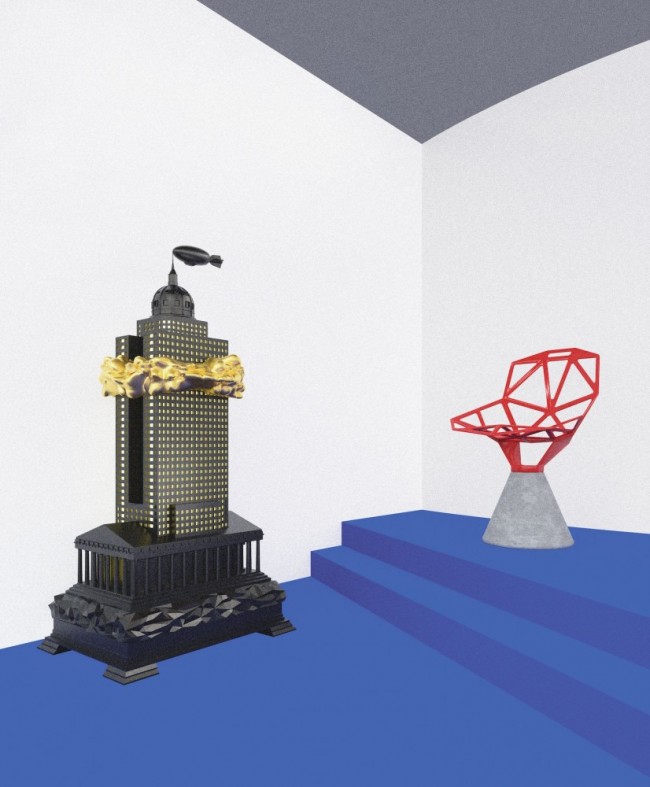

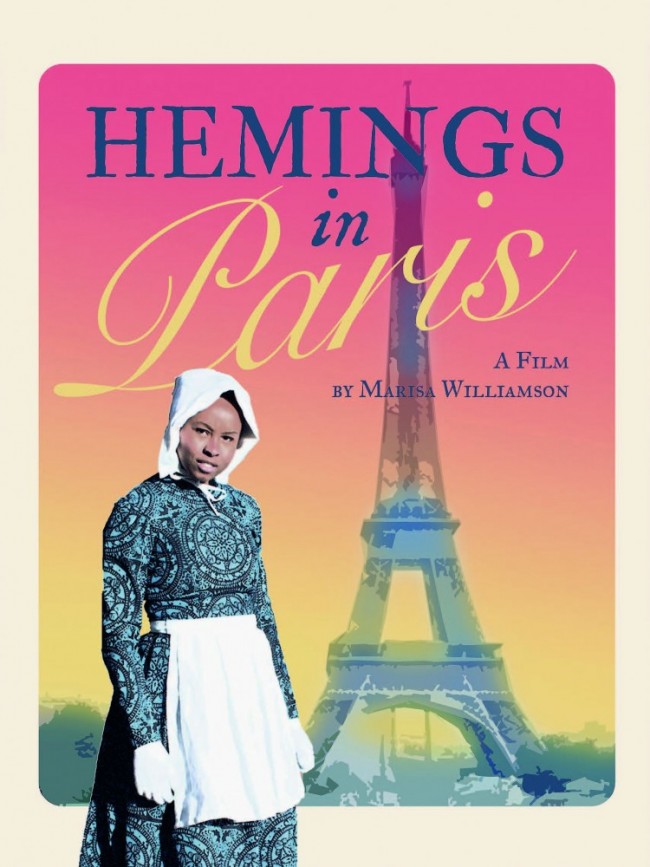

Ilana Harris-Babou, Human Design (2019): video still.

-

Ilana Harris-Babou, Human Design (2019): video still.

-

Ilana Harris-Babou, Human Design (2019): video still.

-

Ilana Harris-Babou, Human Design (2019): video still.

-

Ilana Harris-Babou, Human Design (2019): video still.

-

Ilana Harris-Babou, Human Design (2019): video still.

-

Ilana Harris-Babou, Human Design (2019): video still.

-

Ilana Harris-Babou, Human Design (2019): video still.

Is there also a connection to Restoration Hardware?

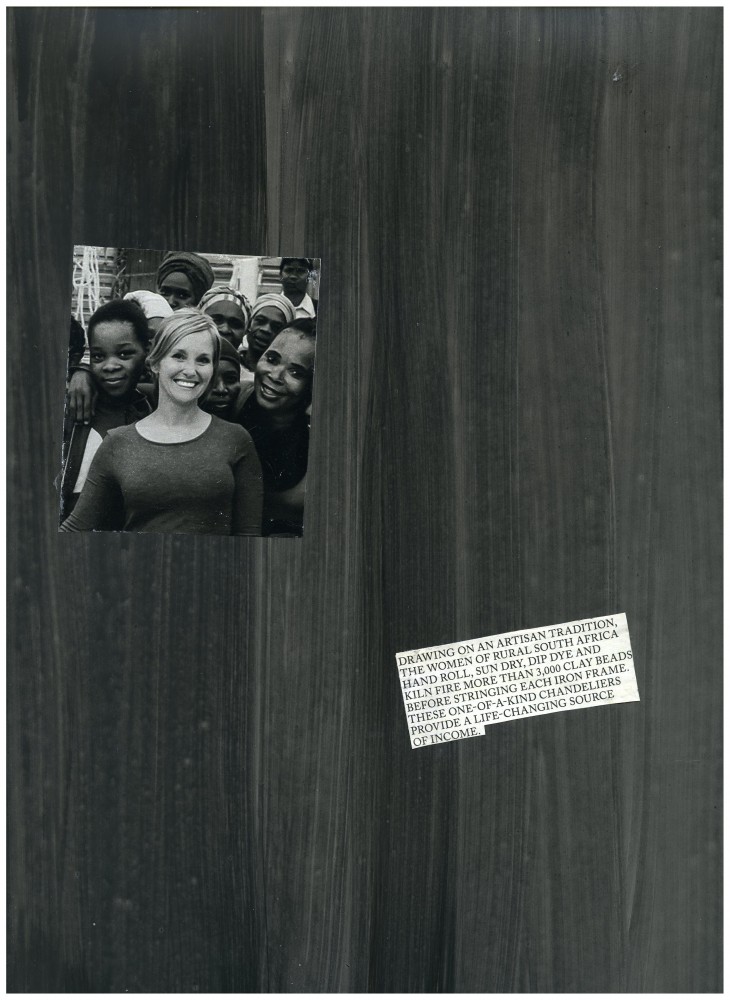

Around the same time they asked me to be in the biennial, Restoration Hardware opened up a store round the corner from the Whitney. I started going there every other weekend, looking around. I noticed African carvings and things like that on display in the showroom. I asked where they came from, and the employees were like, “Oh, our team members go out across the globe and find these one-of-a-kind objects and bring them back, and we share the ones that speak to our CEO. They’re not for sale.” I’d met this art historian named Kristina Wilson, who had been writing about the role that exactly these kinds of objects played in mid-century furniture showrooms. People talked about them in the same way — “They’re not for sale. They’re here to bring excitement.” Charles and Ray Eames went to Mexico and collected pre-Columbian art, and Wilson talked about how these pieces were almost there to reinforce the whiteness of the furniture, to say that it was sleek and could contain the wildness of these objects. So I was like, “Whoa, they were saying exactly the same thing that the person in Restoration Hardware was just saying.” That’s when I decided to make this video where you see a team member going out and finding these one-of-a-kind objects. When I went to Senegal, I went into this touristy restaurant that also sells carvings. I went into the bathroom and looked out the window and they had this dusty hallway that was full of tons of objects that looked identical to the ones in the store, all exactly the same. I guess maybe they had them outdoors, kind of aging them. And they let me shoot part of the video in there. Then I started thinking about the origins of objects and the origins of people. What if this explorer goes out thinking she’s gonna find this authentic object and it becomes confusing whether or not she’s finding her authentic self there? I thought of all the fraught crazy weirdness Alex Haley, the author of Roots, projected onto Africa. And so how am I projecting those things? I go and imagine I’m the African craftswoman making the tourist tchotchke that my explorer self then discovers.

What drew you to these objects in the video specifically?

I came here to the Restoration Hardware store so much. I made replicas of

all the objects ones here. And then in the video, I ended up just featuring the shots with the replicas that looked the best.

What’s interesting is that nothing in this furniture store actually looks unique, apart from these objects.

Yeah, that’s the thing. They’re kind of the wild elements that reinforce the controlled elements.

Because these couches we’re on are kind of ugly. The only thing actually interesting design-wise about them is how expansive they are. It’s so aspirational. Imagine someone in New York with enough space for that.

To have that couch and not have it take up the whole house.

-

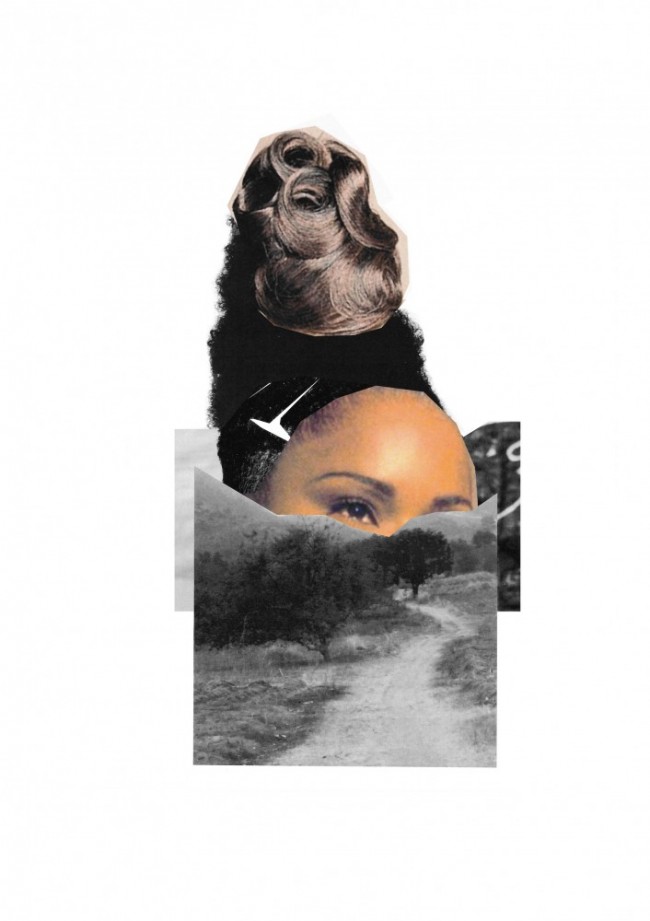

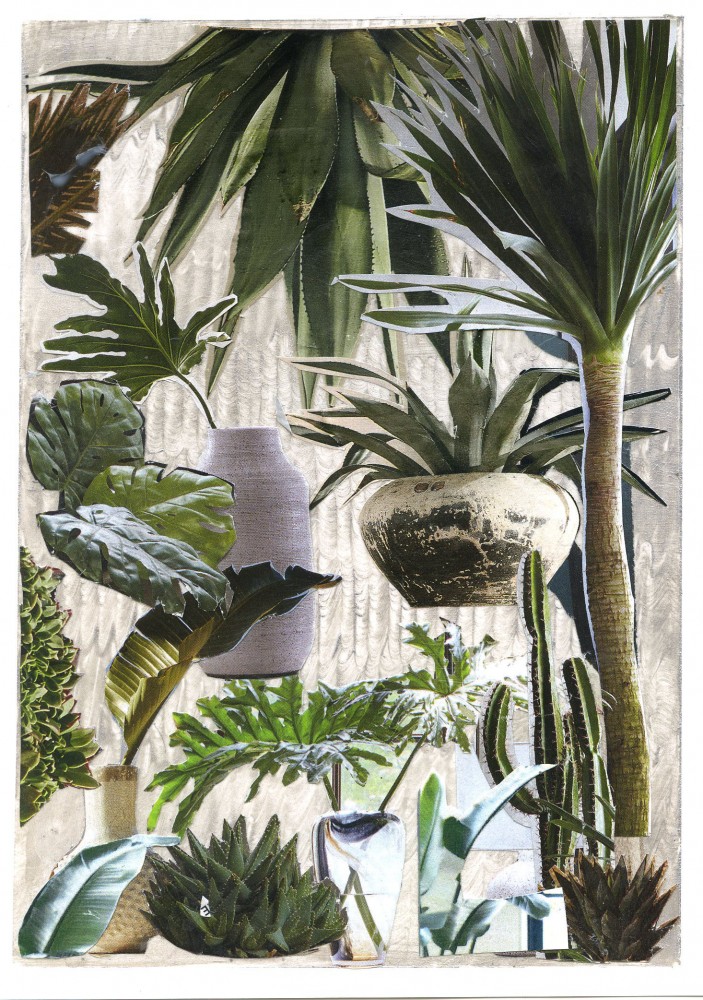

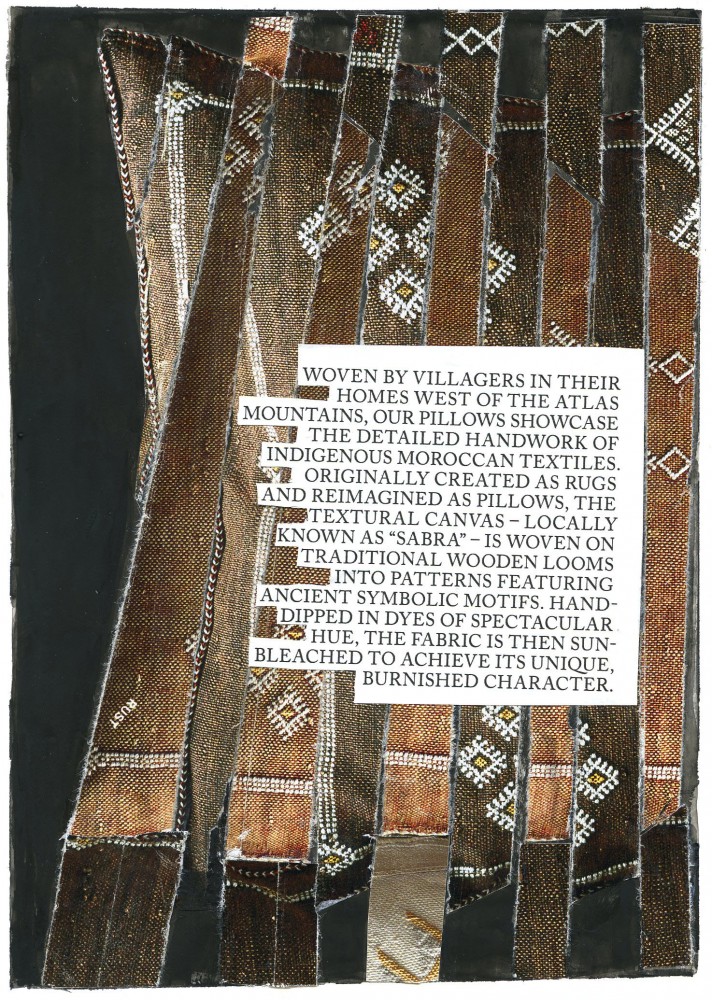

Ilana Harris-Babou, Artisan Tradition (2019): work on paper.

-

Ilana Harris-Babou, Heart of Darkness (2019): work on paper.

-

Ilana Harris-Babou, Hand Work (2019): work on paper.

Are there any other obsessions you’ve had and then abandoned? One of

the things I love about obsession is that it feeds repressed desires for other things, and we constantly reify it with other things. So I wonder what things this obsession replaced?

I went from being obsessed with food to looking at home-improvement shows like This Old House. And now I’m obsessed with thinking about fitness. I’m thinking about how these aspirations play out on the body. Also magic.

Magic is another thing you’re interested in?

Yes. The intersection of magic, wellness, and healing. Like crystals or yoni eggs.

Yoni eggs are really cool. I wish that gay men could use them somehow. I guess we could just put them up our bum. I like the idea that there’s this egg that we didn’t know about but that one culture did, and if you put it inside your body it changes and recharges your energy, right?

Or it’s just a thing for Kegels. (Laughs.)

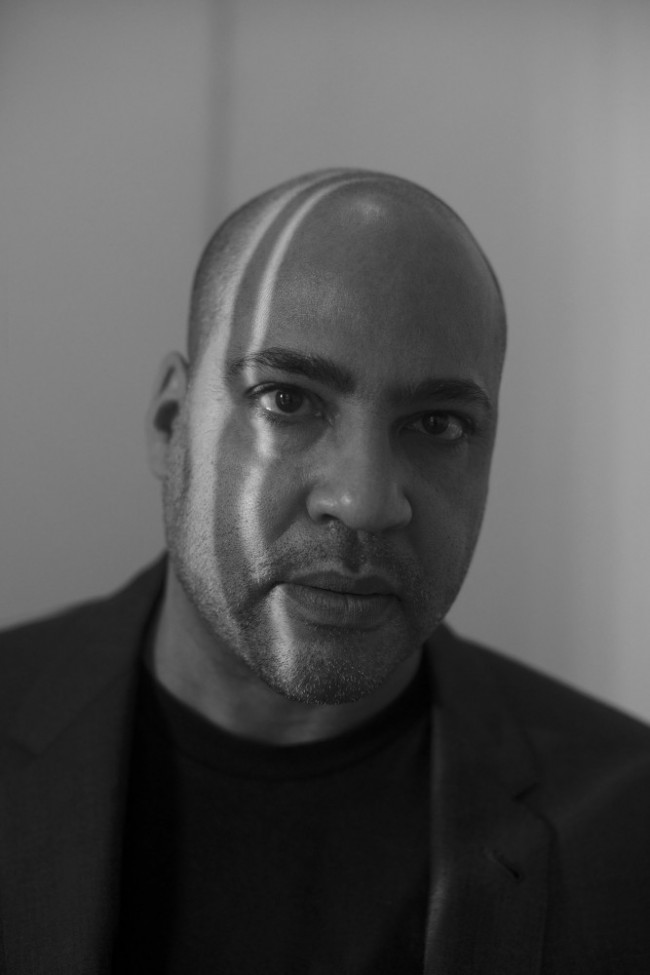

Interview by Jeremy O. Harris, whose Broadway production Slave Play is running through January 19 at the Golden Theater in New York City. Get your tickets here.

Portrait by WangShui. Their first European solo exhibition Horizontal Vertigo is currently on view at Julia Stoschek Collection, Berlin, until December 15.

Photos courtesy the artist and Larrie Gallery, New York.

Taken from PIN–UP 27, Fall Winter 2019/20.