Interview: Jacolby Satterwhite on How Video Games, Art History, and Sleep Deprivation Inspire His 3D Interiors

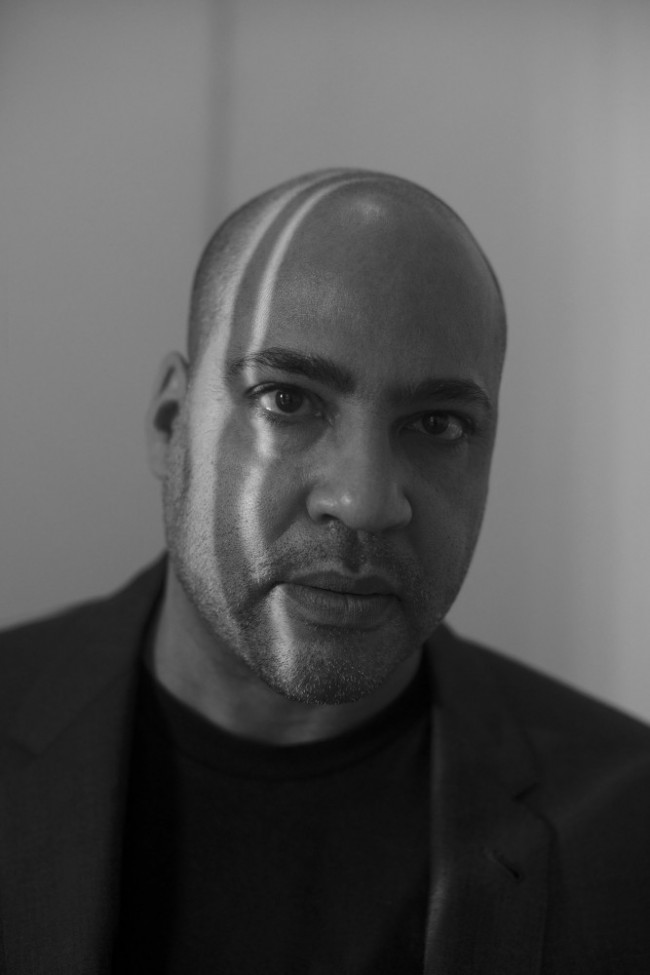

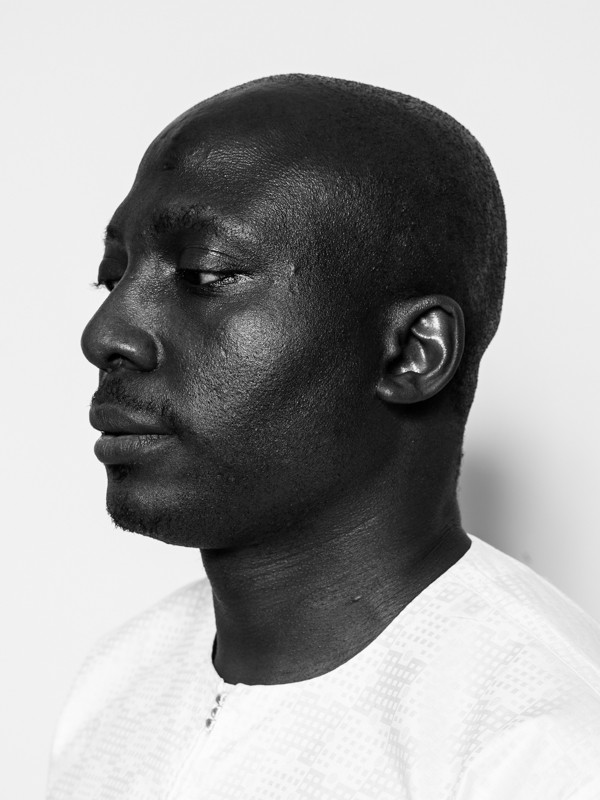

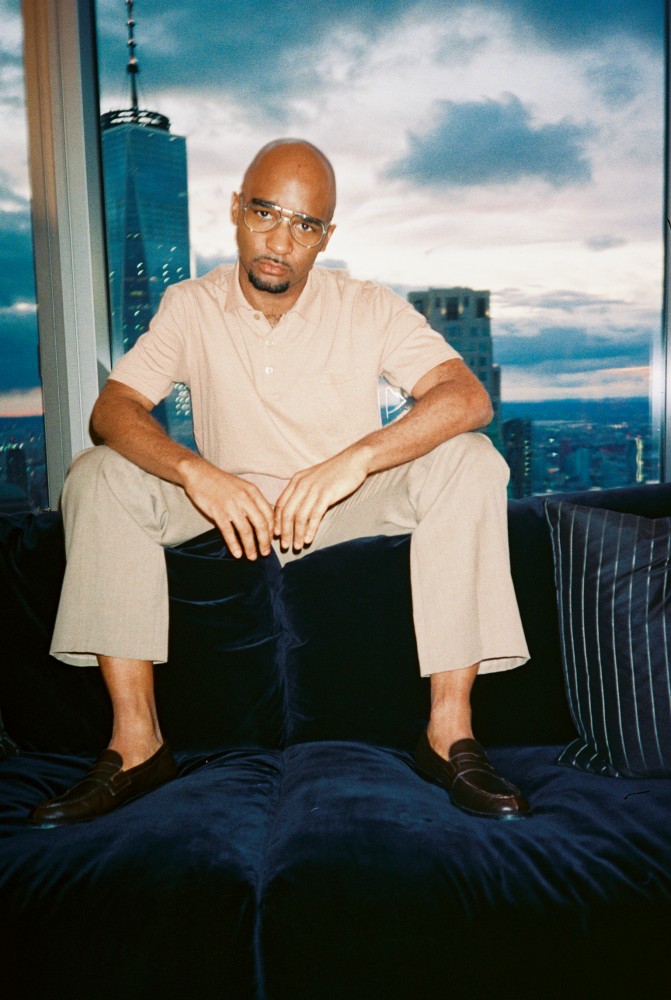

Jacolby Satterwhite photographed by Benjamin Erik Ackermann for PIN–UP.

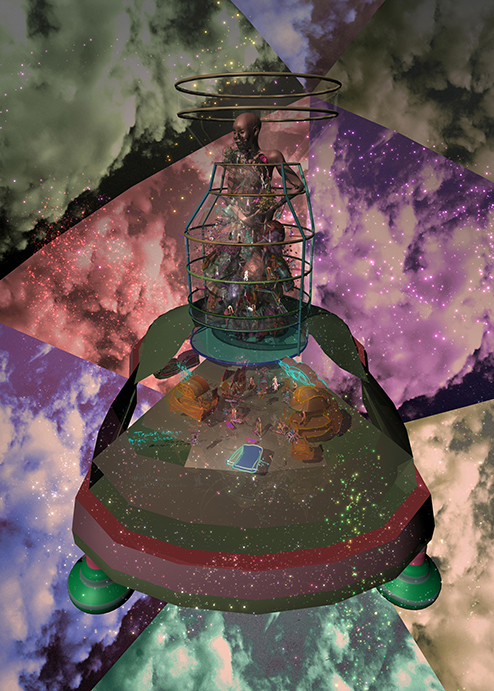

Hieronymus Bosch, ball culture, Piero Della Francesca, BDSM, Josef Albers, and the video-game classic Final Fantasy are just a handful of the radically diverse influences that artist Jacolby Satterwhite has seamlessly synthesized into his own ravishing new world. In Blessed Avenue, the first part of his epic animated trilogy (presented at New York gallery Gavin Brown Enterprises in March 2018), the artist draws on his technical virtuosity to reclaim the video-game environments of his childhood, re-inhabiting them with his own community all through the sharp lens of art history. Under his direction, porn actors, performance artists, musicians, and dancers float together, intertwined in gravity-free sci-fi interiors that equally bring to mind shopping malls in Dubai and after-hours clubs in Brooklyn. Their design is directly informed by (and pays tribute to) the drawings produced by the artist’s late mother, Patricia Satterwhite. As it turns out, even PIN–UP played a small role in the development of virtual environments which Jacolby Satterwhite created as a home for his creative family. Just don’t call them nightlife people.

Is it true that PIN–UP was one of the influences when you developed the architecture in your films?

Yeah. Two years ago (PIN–UP founder) Felix Burrichter commissioned me to create a special project. He definitely inspired me to move. I sent him two samples, but I think he wasn’t feeling them and I didn’t want to spend more time on it, so we never finished the project. But his request helped sharpen my compositional reasoning, which made me a better filmmaker. So I kept pushing it, and I started to realize that I was trying to make classic Piero della Francesca tableaux, because in his paintings everything’s a one-point perspective. I’m interested in proto-Renaissance, Renaissance, and High Renaissance work, because in all three perspective is dealt with differently.

But you’re not interested in the style of architecture from that period?

No, just composition and perspective. When I design spaces in my films, I can go wild, because they don’t have to be built. They become Surrealist, outlandish, and queer.

Your piece Blessed Avenue is packed with seductive, erotic characters. Is your community the client, so to speak, when you create a space?

I’m very empathetic about my entire universe. Everything that I’m networking has to be comfortable, and has to feel right and chic. For me it’s about achieving harmony among all the forms I’m dealing with, whether it’s the buildings, the costumes, or the choreography. The individual elements I work with are linear, but, when they come together, I’ve crystallized each component so intensely that they all expand into something the audience can’t really process.

-

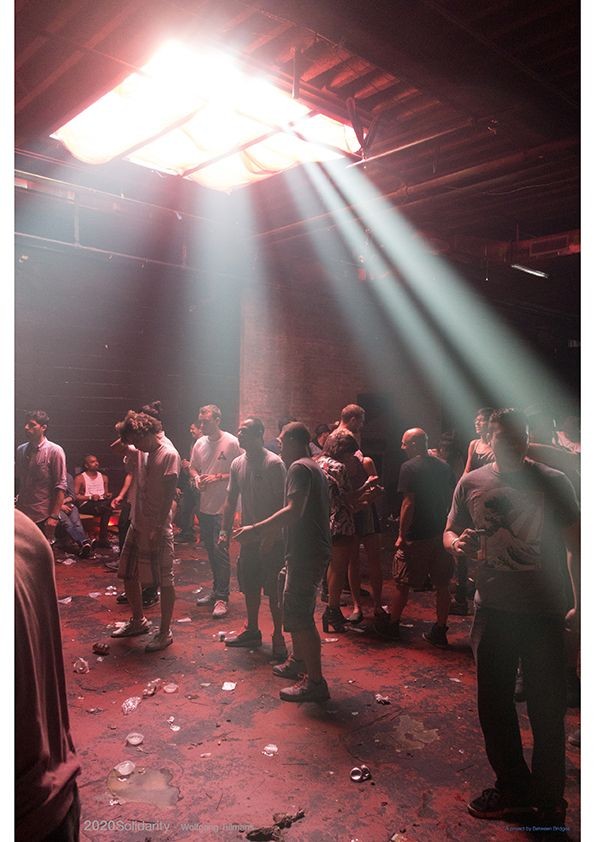

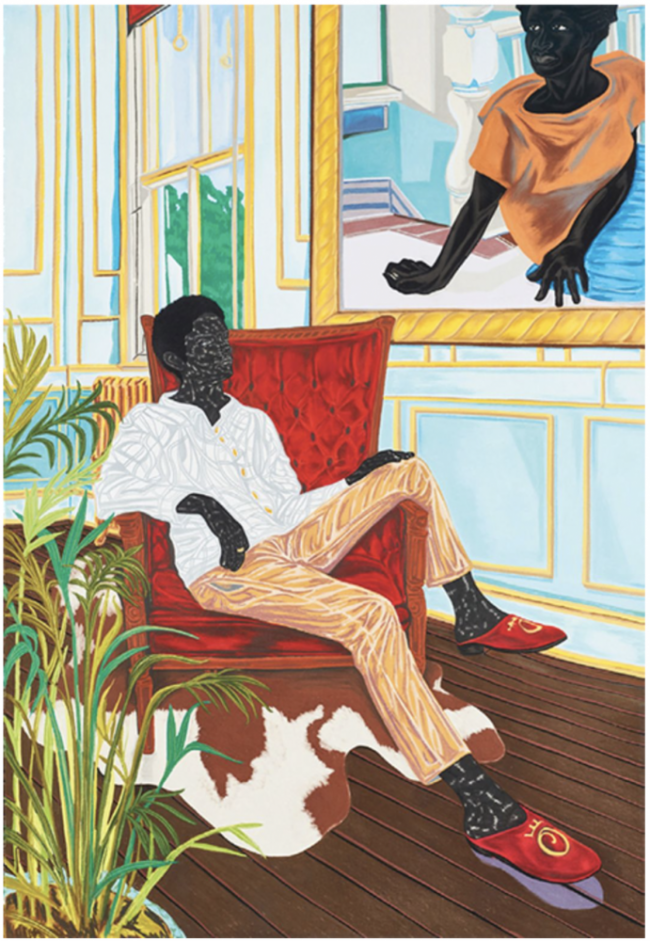

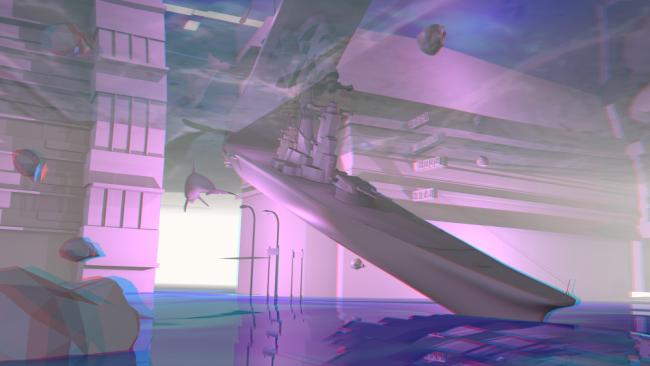

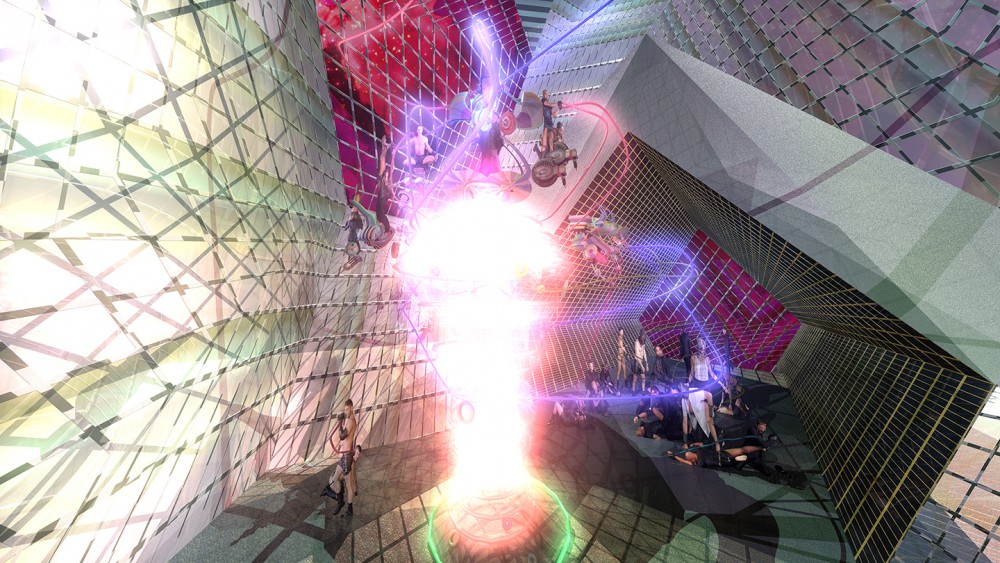

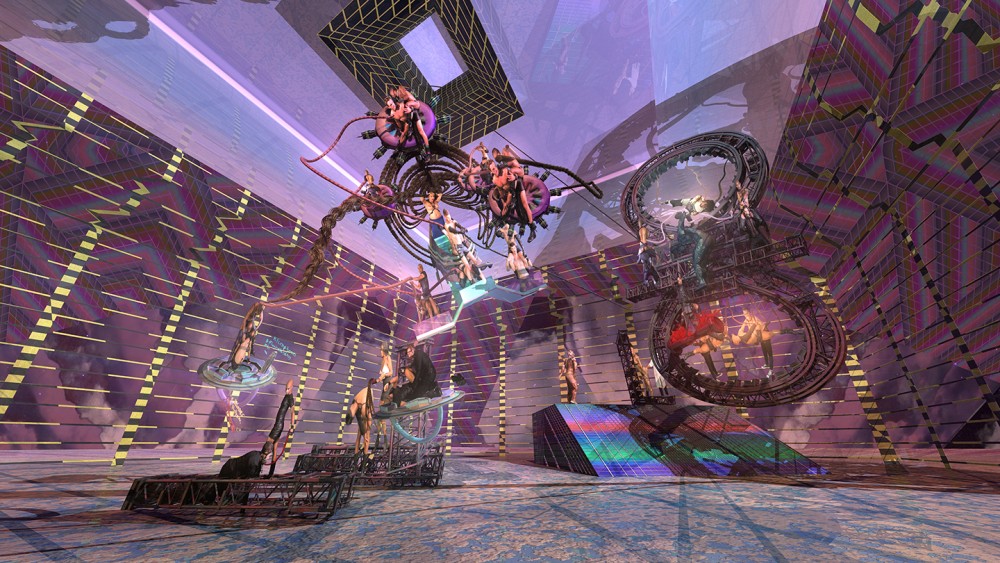

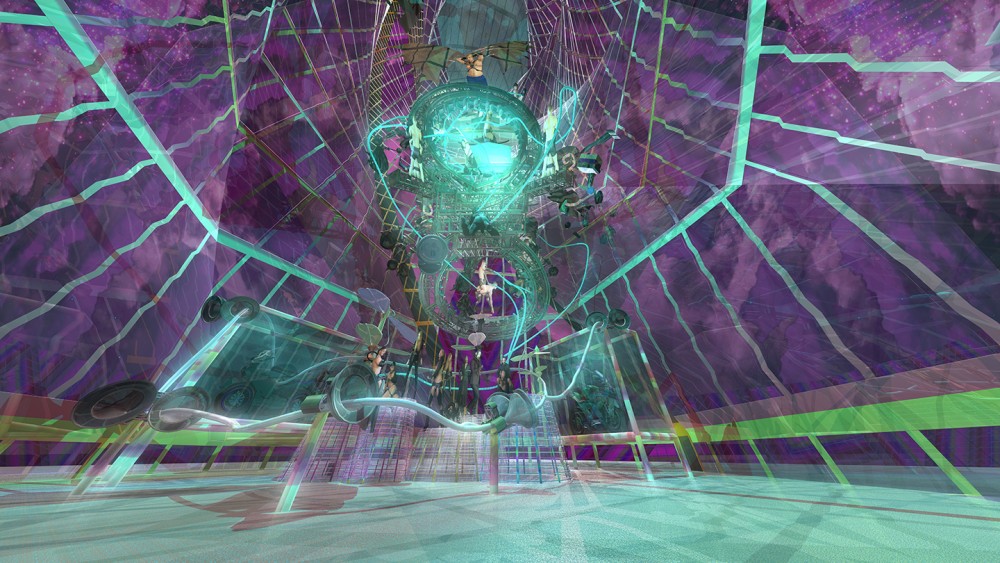

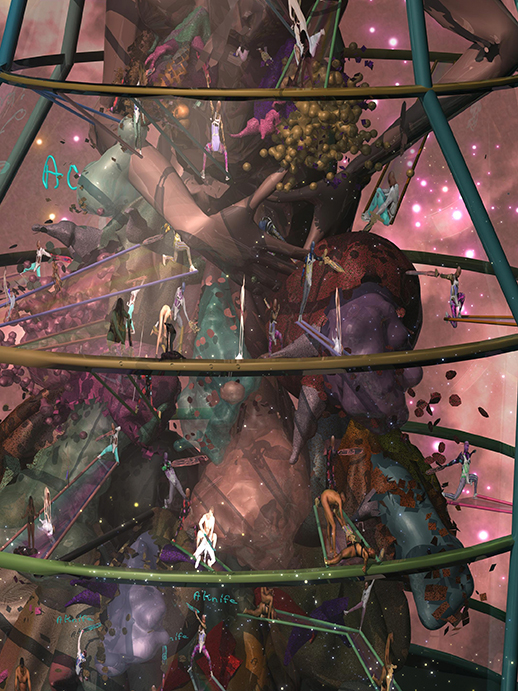

Jacolby Satterwhite, Blessed Avenue (2018) Gavin Brown Enterprises.

-

Jacolby Satterwhite, Blessed Avenue (2018) Gavin Brown Enterprises.

-

Jacolby Satterwhite, Blessed Avenue (2018) Gavin Brown Enterprises.

-

Jacolby Satterwhite, Blessed Avenue (2018) Gavin Brown Enterprises.

-

Jacolby Satterwhite, Blessed Avenue (2018) Gavin Brown Enterprises.

-

Jacolby Satterwhite, Blessed Avenue (2018) Gavin Brown Enterprises.

-

Jacolby Satterwhite, Blessed Avenue (2018) Gavin Brown Enterprises.

Yes — I had to watch the film a few times to wrap my head around it. Beyond the beauty of the spectacle, it’s a truly impressive technical accomplishment.

I spent months just dealing with color. I spent three hours a day rotoscoping every figure. The way I animate is manual and tactile. To make Blessed Avenue I cut my sleeping down to three hours a day for the last few years. The result looks happy but what you’re watching is a commitment. Only other animators can truly appreciate the time and effort it took to create this. I dealt with this processes manually, alone. To get this done you have to be psycho. It’s like I had to do it. I’m a maniac but I had to achieve this in order to survive. I consider it poetry. If I’m gonna make art, I’m gonna make it like this.

Your medium is 3D animation, which is primarily used commercially.

I grew up obsessed with Final Fantasy, and I think I wasted 75 percent of my teenage life playing video games. I have beaten every game and earned the maximum score. In Final Fantasy VII, I won Knights of the Round four times, and that’s a game you have to spend 300 hours playing! I know that space better than anyone else.

So to sum it up through an art-historical lens, your film reclaims video-game space, drawing on your own lived experience and utilizing the talent and personality of your community.

Yes. I took that for granted, but I’m now realizing that I’m contributing to an art-historical discourse. You know the movie Precious? When she’s getting raped her escape is imagining herself performing in a Diana Ross concert. As a kid I had cancer for three years, and for me those gaming universes were my place of solace. Playing Final Fantasy, Resident Evil, and Tomb Raider is what I did every minute I was in the hospital.

Jacolby Satterwhite photographed by Benjamin Erik Ackermann for PIN–UP.

It’s funny to realize those mainstream video games were your starting point, given that your work is so widely discussed as queer space.

My whole fucking life is naturally queer. To be honest, I don’t even like the word. For me it’s become art-world click bait because that’s what curators currently write their dissertations about.

But the figures that inhabit your world are living what could be considered queer lives: artists, porn actors, dancers, musicians — all the fun people of New York that come together through nightlife.

It’s my version of Warhol’s Screen Tests. I’ve captured everyone on green screen. I direct the choreography, film them, and add them to my archive. I have thousands of bodies on my computer. Then I make these architectural sites and inhabit them with whatever creates a harmonious composition and makes the image move elegantly and express what I’m trying to say. So figures are sometimes dormant on my hard drive for six years.

How do you select them?

They’re mostly friends. I love everyone in my film. My practice is to capture them in isolation in order to celebrate them. I spend so much time with each figure because I have to trace them. For every single figure in that video I’ve spent at least eight hours putting a dot on their hand, over and over and over and over and over.

You put a dot on their hand?

Yes, because I’m tracing that frame by frame. So I’m really committed to these people. When you see Lourdes (Leon) in the roller coaster, for example, I traced her head, I traced her hand — I know that girl too well, I feel like I’m related to her, and it’s awkward when I see her because we’re not even that close... I spent 12 hours a day with these people on my computer for months and months, until they felt like family.

And many of them are your chosen or creative family. Which leads me back to queer space: if you don’t like that term, what would you say instead?

I’m technically a queer artist. I definitely consider it a queer space. I’m the definition of having a queer lexicon. Because outside of the homosexuality aspect, I’m an African American dealing with my mother’s mental illness, dealing with outsider art, dealing with alternative sexual practices, dealing with sadomasochism and dealing with the complex nuances of the desire spectrum. So obviously everything about my work is a delineated queer experience, and I’m definitely negotiating those terms and these alternative virtual effects, so phenomenology is a big part of my practice. I read a lot of books about it in college, because I was sick of being defined. So phenomenology as a philosophy makes sense to me because it’s about what happens when a librarian sits at a table, what items would a librarian have? And when a chef sits at a table they have a knife and a fork. A teacher has an apple. An artist has a pencil or paintbrush.

So it’s about combining new types of signifiers and events?

My mom made drawings about objects, materialism, and capitalism — “I want to have a house,” “I want to have a picket fence,” “I want to have a raincoat.” So when I make 3D animations and I deal with architecture, I can make up anything I want. I make alternative universes — it’s my own planet, it’s my own hegemony. So when the viewer comes into my space, they have to assimilate to my standards, my phenomenology. I put people into spaces that have these weird, curvy, linear forms that don’t make sense. And you have to reformat what it means to have this figure dancing around in basically a new lexicon.

At first view I’m seduced by the bodies engaged in light BDSM and vogueing, but then I realize that I have never seen those activities depicted in interiors like these. To me the spaces you’ve created look partly like civic spaces as imagined by Zaha Hadid, and partly like a mall in Dubai mixed with the feeling of an after-hours club in Brooklyn, like the Dreamhouse.

Well, I like the fact that there are associating signifiers, but the thing is, it’s not a nightclub. The people are from nightlife… Actually, they’re people. Why do we label them that way? I think they would be insulted. Can you imagine if someone introduced you as “Michael from nightlife”? Everyone wakes up in the daytime and goes to Starbucks. What if people said, “He’s from Starbucks.” Jacolby made this film where everybody’s from Starbucks!

(Laughs.)

What I’m making is more about asking, “How do I use architecture, performance, and sexuality? How do I use the human condition? How do I reflect my experience as a person living today through this medium?” You know who I reference continuously? Color theorists Josef Albers and Johannes Itten. They put colors next to one another to see how they work together. And that’s how I think about my archives. I have probably 100,000 files on my hard drive of people, architecture, objects, and reference images, and I network them like a Rubik’s Cube. Albers and Itten would look at how a pale yellow would sit next to a bright yellow, and that’s the same way I’m playing with subjectivity.

So instead of juxtaposing colors, you’re matching aura and personality?

Aura, color, people, architecture, reference images, performance. Those figures engaged in BDSM — that’s not about pleasure, it’s about labor. Consumerism is about desire, sexual appeal, and seduction. Did you notice how everyone’s controlling each other while they work towards producing something? It’s labor that’s ambivalent and ambiguous. The person on top may secretly be controlled by the person on the bottom. You know how in life, there’s rich and there’s poor? The rich think they’re in control, but we’re all a part of the same system. That’s the metaphor. It’s really my own truth. I usually keep it to myself because I want people to receive it in their own way. I’m just a poet trying to resolve things. When I make more work, people will understand what I’m saying.

-

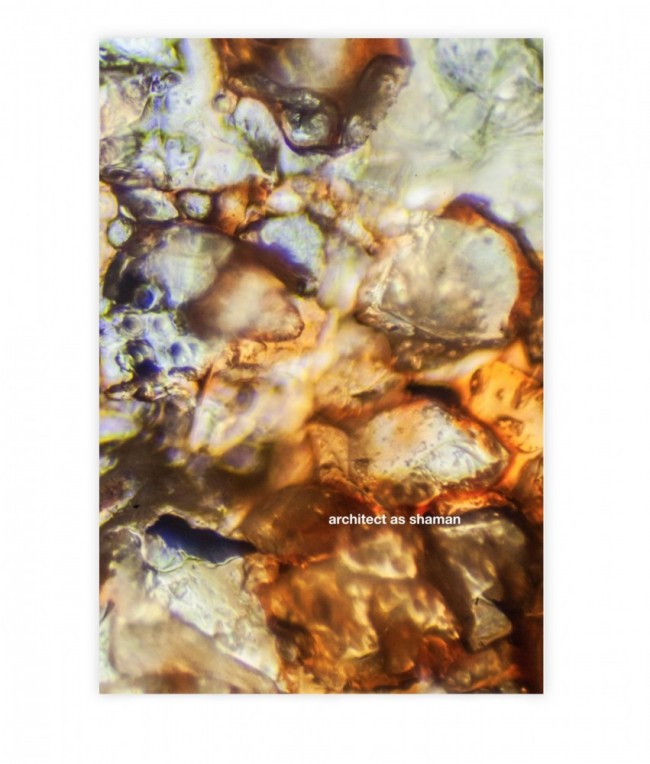

Detail for Epacide, an unfinished work by Jacolby Satterwhite for PIN–UP 19, 2015/16.

-

Detail for Epacide, an unfinished work by Jacolby Satterwhite for PIN–UP 19, 2015/16.

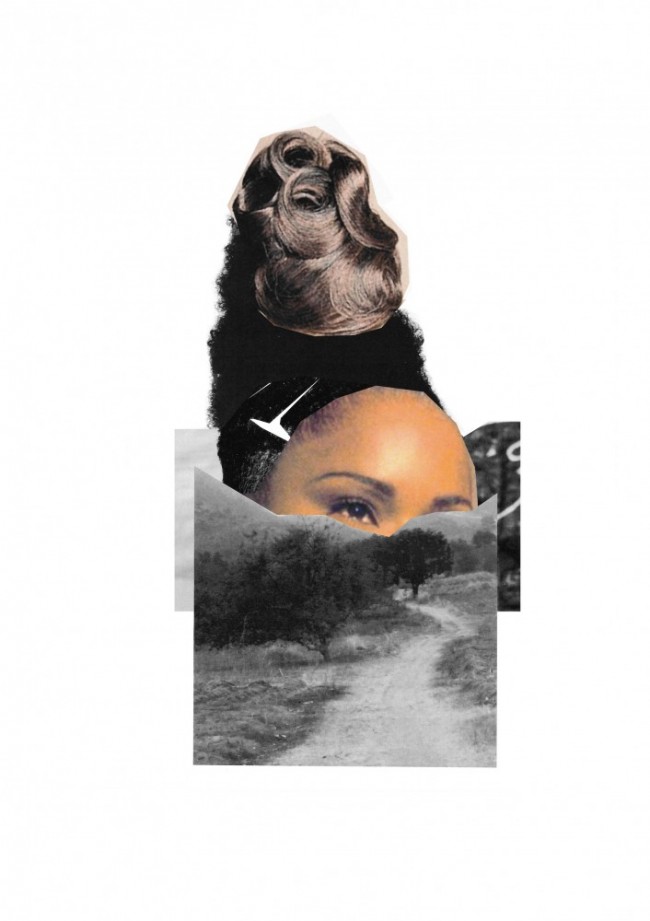

-

View of Epacide, an unfinished work by Jacolby Satterwhite for PIN–UP 19, 2015/16.

Text by Michael Bullock.

All portraits by Benjamin Ackermann for PIN–UP.

Taken from PIN–UP 25 Fall Winter 2018/19.