Still from the Lavaforming film. Courtesy of s.ap architects.

The 2021 Geldingadalir volcano eruption. Photo by Thrainn Kolbeinsson courtesy of s.ap architects.

The year is 2135; the place, Iceland. In her twilight years, 89-year-old Lisa Frey remembers her youth, when her home city of Eldborg was “still hardcore, when there were still streams of lava, still some ash and smoke, still a few spills and mistakes and disasters that influenced our identity and made us feel very real.” Now, Eldborg is transformed, a city of glassy basalt domes, of giant poured pillars, filled with palm trees, wildlife, fruit, and abundance. Looking back, Frey comes to understand how the city’s dystopian development “taught us to live with other things. The Ark, the flowers, the spare copies of our old planet, waiting for a time when we could open the doors, replant, regrow, reclaim the nature we had only seen on ancient TV shows.” In a childhood dominated by the environmental crisis, people made do with AI animals, many of which had never actually existed. But older Eldborgians nonetheless miss them, sighs Frey in this post-apocalyptic scenario, which was dreamt up by author Andri Magnason for the Icelandic National Pavilion at the 2025 Venice Architecture Biennale. Curated by architects Arnhildur Pálmadóttir and Arnar Skarphéðinsson, the display, titled Lavaforming, marked the first time the tiny volcanic country (population 384,000) has taken part in the event.

The Icelandic Pavilion. Photo by Ugo Carmeni courtesy of s.ap architects.

Still from the Lavaforming film. Courtesy of s.ap architects.

Still from the Lavaforming film. Courtesy of s.ap architects.

Many of us remember the eight days in April 2010 when European airspace was closed due to the eruption of Iceland’s Eyjafjallajökull, a reminder of the constant threat posed by the country’s volcanoes. Indeed, among the exhibits at the Arsenale this year is Volcanic Infrastructures (Cristina Parreño Alonso, J. Roc Jih, and Skylar Tibbits), which considers how Iceland’s power plants and other critical installations might be protected from eruptions without resorting to environmentally damaging, material-intensive solutions. At the Icelandic Pavilion, Pálmadóttir and Skarphéðinsson wonder if, in fact, the answer might not lie within the volcanoes themselves. What if the huge amounts of material that burst forth from the Earth’s crust every year could be channeled as a naturally occurring building material? What would a city made from poured lava look like?

As architect Logi Einarsson — today Iceland’s minister for culture, innovation, and higher education — pointed out at the pavilion’s opening ceremony, the country has never had much in the way of construction materials. Historically, with no forests, the only source of timber was driftwood, and the tiny fishing nation has no tradition of building with the hard-to-work basalt that forms when lava cools. Traditional homes used earth, turf, and found timber. Since the mid-20th century, concrete has dominated Icelandic construction, sometimes with basalt as aggregate, though that involves smashing and crushing it, which raises the concrete’s already poor carbon footprint.

With lava, however, Iceland may have a readymade low-carbon solution for a whole range of its construction needs, since the magma that emerges red-hot from the Earth’s crust is capable not only of forming solid basalt masses but, if it cools rapidly, glass-like obsidian; moreover, basalt can also be used to make weavable fibers that are stronger than carbon fiber. “So the walls, windows, roof, and insulation could all be made from the products of lava,” explains Skarphéðinsson. As such, the result might be a sort of mono-material, pre-fabricated basalt-and-obsidian structure, a solution that contrasts sharply with attempts at low-carbon building in other parts of Europe, where a heterogeneous mix of materials tends to be the norm.

There remain, of course, questions of feasibility, which the curators have begun to address by putting together an interdisciplinary team that includes geologists, construction engineers, and software programmers. To start with, lava flows are irregularly occurring phenomena, but the Lavaforming group has been working with the software that scientists use to predict eruptions in Iceland (they even managed to improve it, when coders in the team fixed its glitches). Soon, say the curators, they’ll be digging channels to test empirically what happens if you attempt to divert lava. And, of course, further work needs to be done to understand the material properties of the magma that pours forth from the ground and how cooling times and other factors affect the final results. Then there are the ethical questions, which appear particularly acute in a tiny country still traumatized by its 2008 banking collapse, and whose parliament is currently trying to legislate for fairer fishing tariffs, to the detriment of the big groups that have long reaped huge profits. Would lava be the property of the landholder, like oil, or should it belong to the nation, like fish, which are a common resource under Icelandic law? Should lava exploitation rely on natural availability, or might one drill for it, again, like oil? And if so, what are the dangers?

Still from the Lavaforming film. Courtesy of s.ap architects.

Detail view of Lavaforming. Photo by Ugo Carmeni courtesy of s.ap architects.

Lava material test. Photo courtesy of s.ap architects.

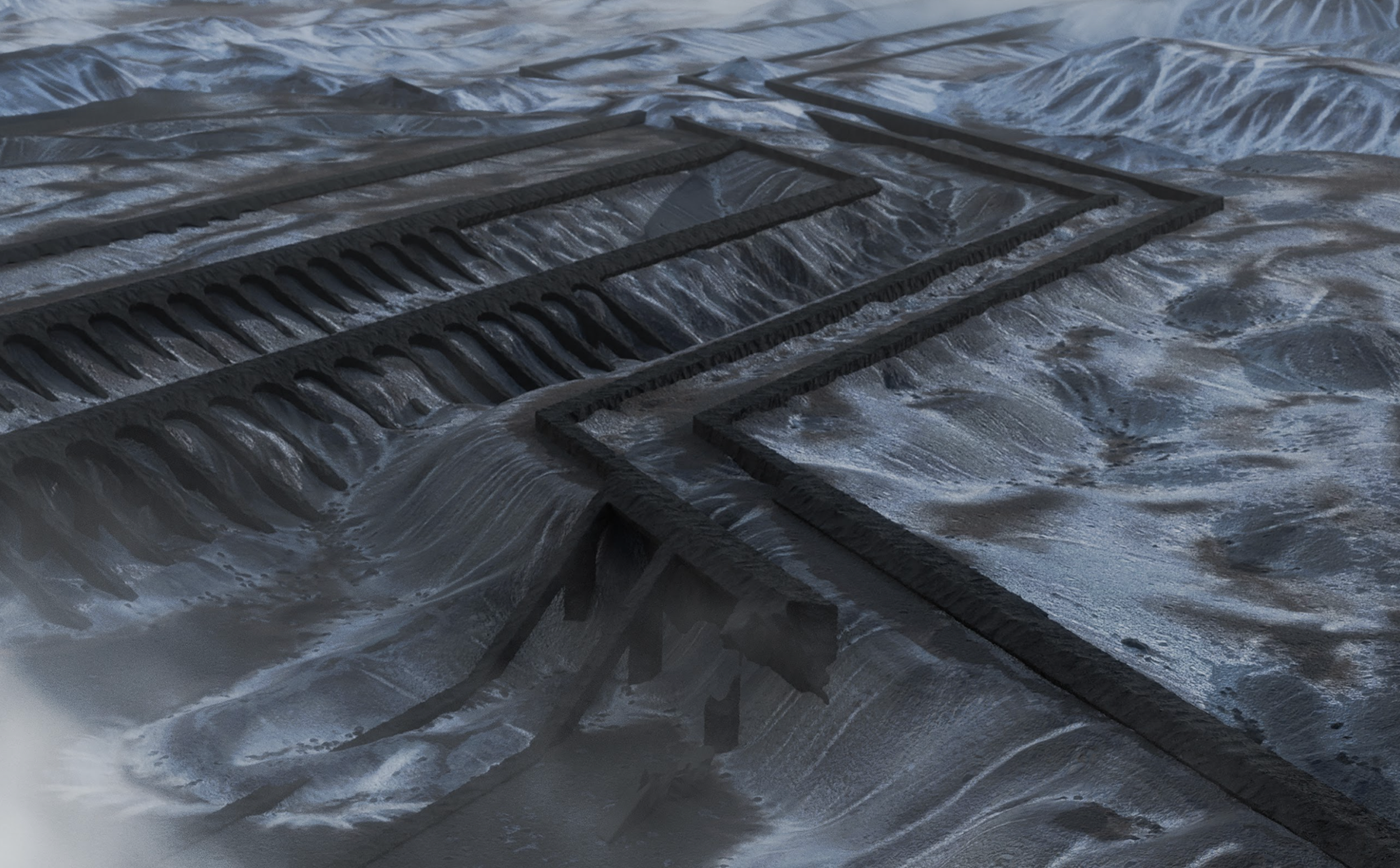

All of this and more is considered in the Icelandic Pavilion, where the terrible consequences of monopolies and of over-supply disasters are imagined; where experiments in lava re-smelting are displayed; and where images of Eldborg, built by AI robots that can harvest and 3D-print magma, display an aesthetic its creators describe as “lavapunk” (derived from the term “steampunk”). Even Icelandic folklore has been woven into the narrative: ancient tales of stone ships, or Steinnökkvi, seem to herald basalt-fiber vessels; legends of a hidden people living in the rocks evoke the idea of climate refugees taking shelter in lavapunk caves; while the myth of the Eldjötnar, or fire giants, heralds the huge machines that might build this troglodytic city. “Magma is the only resource that is sure to outlast us,” says Pálmadóttir, since scientists predict that the sun will have swallowed up the Earth long before our planet hardens. What if, in the end, all of this was written in the runes?

Still from the Lavaforming film. Digitally rendered, “lavapunk” landcape. Courtesy of s.ap architects.