Photographs provided by the PinchukArtCentre © 2021. Photographed by Maksym Bilousov.

Henrike Naumann photographed by Nadine Fraczkowski for PIN–UP 32.

When we spoke in early 2022, Henrike Naumann was just a few weeks away from her first-ever visit to the U.S. — a research trip for the Berlin-based artist’s stateside debut, opening at New York’s SculptureCenter on September 22. The day she touched down in New York, Russia invaded Ukraine. At the time, Naumann had work on view in both countries. At the new Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow, she was part of Diversity United: a controversial multi-city project from which a number of artists — including Naumann — have since withdrawn, citing, among other things, its organizers’ ties to Vladimir Putin. In Kyiv, she was showing at the PinchukArtCentre as a nominee for the annual Future Generation Art Prize. Naumann’s installations use an intimate language of domestic interiors to express the complexities and contradictions of political ideology. Recently, she participated in the 2021 Ural Industrial Biennial of Contemporary Art in Yekaterinburg and Illiberal Arts at the Haus der Kulturen der Welt in Berlin. She held a solo exhibition, Einstürzende Reichsbauten (Collapsing Reich Buildings) at the Kunsthaus Dahlem, located in the former state-sponsored studio of Nazi sculptor Arno Breker. The show was exemplary of an artistic practice in which elements of home and institutional décor, each with their own meaning or association – a piece of canonical Nazi furniture, a postmodern design motif or East German souvenir from the 1980s — are combined to narrate recent histories both ineffable and unspeakable, beginning with Germany’s own. When she was born — in 1984, in Zwickau, East Germany — the German Democratic Republic (GDR) celebrated its 35th birthday with the highest GDP in the Eastern Bloc, a promise from its president, Communist Party chief Erich Honecker, for “secure peace,” “the strengthening of socialism,” and “a happy life” free of fascism, as well as what the Washington Post described as a “mood of quiet despair.” I was born that same year in San Francisco, when crack cocaine was hitting American cities, the virus that causes AIDS was identified, and Ronald Reagan stood for reelection. Apple also launched its desktop revolution in 1984 with an Orwellian television commercial for the first Macintosh: a runner wearing what looked like a Hooters uniform charged a Big Brother-style telescreen and then smashed it with a mallet, liberating its brainwashed audience from the propaganda machine holding them captive. The campaign promised a product that would show viewers at home “Why 1984 won’t be like 1984.” We can think of 1984 as a cusp year of sorts, a time of in-betweens and presages in which consumption was globalized and its objects subjectively received. Naumann and I share our birth year with Miami Vice and The Cosby Show, and grew up on opposite sides of the Iron Curtain with with the same TV sitcom living rooms glowing in the backgrounds of our childhood homes. What Naumann’s work so successfully achieves, in the intimacy and specificity of her environments, is a depiction of experiences shared despite difference, and of the disparate understandings — and violent creeds — that can be nurtured in similarity.

With Ostalgie in the 2022 exhibition Diversity United at Moscow’s New Tretyakov Gallery, Naumann showed Postmodern finds alongside neo-prehistoric objects and odd-ball merch featuring paens to East German identity. Photo Courtesy New Tratyakov Gallery.

Victoria Camblin: We were both born in 1984. I, in San Francisco, California, and you in Zwickau in GDR. I’m curious about what parallels we might find in our childhoods despite being raised on different sides of the global north under wildly different political systems. Your interiors remind me of my childhood as much as, possibly more than, they conjure another time and place entirely.

Henrike Naumann: You know, until recently, the closest I ever got to the United States was Port-au-Prince! In the GDR, it wasn’t possible to travel to the West, and after the Wall fell my parents didn’t have the money for it, and I was always more interested in going to the East — or to Kinshasa, Cuba, or Haiti, where I’ve done several projects. As I got closer and closer to America, I was able to experience it from the very radical perspective of these other places. Even though my work is known to be very influenced by the history of the Eastern Bloc, it’s also about the West.

Wherever you are, America comes to you — that’s the cultural imperial project. Why bite the bullet now, in 2022?

When East Germany was Americanized in the 1990s, it was like a bootleg or secondhand version of what you got in postwar West Germany, with the allied concept of Western democracy. But I hadn’t really thought about going to the U.S. to explore this outside the very specific German historical landscape until the storming of the Capitol. That opened my eyes to the idea of showing in the U.S. — and of not just having it be this exotic story coming from somewhere else that you look at from a distance. I wanted to explore what it would mean to see my work in this country that I only know from TV — and I maybe know it a bit too well from TV, which has made the U.S. even more unreal. My visual imagination is very influenced by the American television I watched in the 1990s, starting with The Cosby Show and especially The Flintstones, which has been really insightful to revisit. This is a show that was produced in the 1960s but set in the Stone Age: it’s as though the U.S. was claiming that the consumerist middle-class family had been around since prehistoric times. In my work, I contrast “the monotony of the ‘Yeah, Yeah, Yeah’” [as GDR leader Walter Ulbricht, described Western music in the 1960s] with the idea of “primitive communism” from Marxist-Leninist theory — the creation of the “real” human in pre-modern societies through tools and labor. The Flintstones doesn’t imagine any past beyond the capitalist system, and their whole modern, Western, American lifestyle can only be maintained through the use of dinosaur labor. These animals do all the physical work that allows them to have automatic trash cans. It’s not only about the eternal capitalist society, it’s also a normalization of exploitative labor and slavery. As a child, this was how I learned about the U.S. — and it put certain images and desires and fantasies in my mind as we experienced the shift from socialism to capitalism and the friction between those systems. I think that’s why I am able to look in both directions and not take anything as normal or as without some alternative.

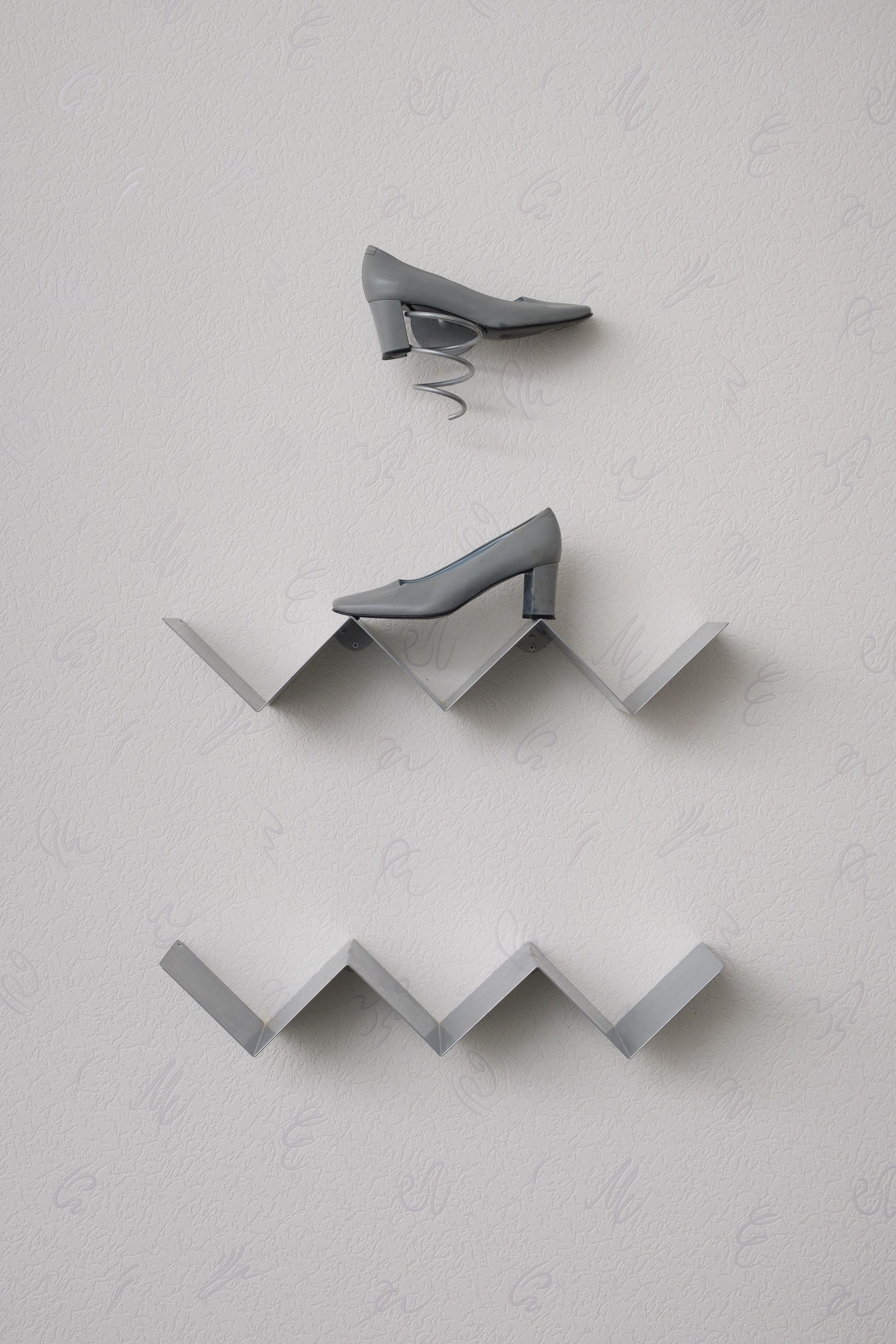

Photographs provided by the PinchukArtCentre © 2021. Photographed by Maksym Bilousov.

Photographs provided by the PinchukArtCentre © 2021. Photographed by Maksym Bilousov.

Photographs provided by the PinchukArtCentre © 2021. Photographed by Maksym Bilousov.

There isn’t a lot of friction in 90s sitcoms — they’re somehow aspirational even in their darkest moments. Aside from the unusual visibility of its exploited, “othered” laborers, The Flintstones follows the same archetypal format of all sitcoms: the nuclear family with two kids — a boy and a girl, plus sometimes an accidental baby —, the aggravating neighbor, the gendered division of household roles, the husband emasculated by his boss at work but respected at home. That’s the extent of their exteriority: everything else happens inside the home. The opening credits of Full House showed San Francisco’s iconic “painted lady” Victorian houses, but, if I remember, the city had no bearing on what went on in the show. Nobody fucking went outside. Is your work about these interiors, domestic backdrops for our individual projections?

We all watched Full House in East Germany in the 90s — so you and I watched the same things. There was also a cartoon about rats, mice, and roaches living in the White House that I had completely forgotten about until I began researching the storming of the capitol — Capitol Critters. It’s about this mouse living in the countryside until the whole family is killed by a poison. The mouse goes to Washington, D.C., and moves into the Capitol where there are all these other rodents — a laboratory rat, mice from different places — who overhear all the White House politics, and you always see the president’s legs walking around.

Oh. My. God.

It was supposed to be a big hit, like The Simpsons, but it was canceled after one series, dubbed, and sent straight to Germany.

Too political?

Perhaps. But The Flintstones is just as political, a cartoon history re-written to a capitalist agenda. Of course, the other narrative is that there have been alternative systems to capitalism, but they all failed, and though the system might not be good, it’s the best we have, and we have to live with it because no one has been able to imagine and put into practice anything better.

Simultaneous to the Diversity United show in Moscow, she presented 2000 (2018) at Kyiv’s Pinchuk Art Center. Already before the Russian invasion of Ukraine, numerous artists had pulled out from Diversity United — which intended to present how the “artistic face of Europe is complex, diverse and permanently in flux” — following protests around its curator Walter Smerling at the Kunsthalle Berlin, where the exhibition debuted. Plans to take the show to Paris were scrapped after German funding was withdrawn from the Putin-backed project.

Yet we can imagine a distant past in which dinosaurs and fully automated appliances rule the world together. In your work, though, opposing systems and epochs do co-exist — and you achieve that through anachronism, using household objects and furniture to create layers of references from clashing times and places.

I started thinking about those layers of time in 2011, after a long wave of murders committed by a terrorist group called the National Socialist Underground [NSU] from my hometown, Zwickau, was finally exposed. Suddenly I realized I’d been living in a place where I was surrounded by an entire network of neo-Nazi terrorists every day. That’s what led me back to the 1990s: I wanted to look at this moment of awakening, when the West German neo-Nazi groups and the East German radicals joined together, and speak about what led young people to the neo-Nazism we have in Germany today. I mean, there were pogroms in Rostock-Lichtenhagen [a housing project in the suburbs of Rostock]. I realized I couldn’t really explore the 90s in the sole context of post-reunification Germany: I had to speak about the GDR too, to understand the post-socialist condition, and looking at the GDR I reached the understanding that I cannot speak about East Germany without speaking about West Germany, and that I cannot speak about the postwar situation without speaking about World War II itself. Connecting far-right ideologies in West Germany and the GDR with National Socialism revealed continuities that run through families — certain ideas of society that are handed down from generation to generation. And that entire legacy is contained in furniture.

You’ve spoken elsewhere about seeing fascism in furniture, and about the “evil lies of everyday objects.” I connect that to something I call the lie of the “new,” the idea that whenever we put “neo” or even “post” in front of anything, we’re actually telling a lie by suggesting it ever went away. To talk about “neo”-Nazism in Germany suggests there was a time when it had ceased to exist here, which is not the case.

No — not anywhere, and especially not in Germany. I did a project in Chemnitz a couple of years ago that developed this idea of alternatives to capitalist society. Chemnitz has gotten a lot of media attention for all the far-right marches that happen there, and it’s very close to where I’m from. We were installing at the big Karl Marx monument, so I booked a hotel nearby. I was horrified to find it was in the same building as a neo-Nazi clothing store that named Anders Breivik. It turned out the hotel itself wasn’t run by NSU supporters — the whole property was owned by a West German guy who bought it after the fall of the Wall, and wasn’t thrilled about the store but thought, “Hey, it’s a business.” The building, for me, became a symbol of what was going wrong in the entire city. When the first lockdown came round, I went back to shoot a film in the rooms there, which were all in different pastel colors. What’s interesting is that my assistant at the time was from the Bay Area, and he told me the hotel totally reminded him of growing up in California. We were in this super 1990s East German hotel in Chemnitz, and someone raised in Silicon Valley was telling me, “Wow, this is my childhood, but it’s a place I could never travel back to.” And I’m like, “This is my childhood too, but it’s a place that never seems to go away.” People ask me why I always go back to the 90s, but they’re still so present in the former East — the aesthetic is still there in a place where buildings were renovated once during an investment boom after the fall of the Wall and never touched again. But I never expected that someone from San Francisco would also have feelings like that about these places.

Henrike Naumann photographed by Nadine Fraczkowski for for PIN–UP 32.

People keep wanting to talk to me about the “return of the 90s” — by which I gather they mean the revival of a Postmodern aesthetic that people of our generation used to find gauche rejected for a while. I’m not sure it’s relevant to talk about decade “returns” anymore, but maybe what’s interesting about that period is the question of rapid change — one associated with a dilution of authenticity. In the 90s, San Francisco, like many American cities, got richer. People had more money and built new kitchens in muted “California” yellows and adobes — which is the same palette you describe in the hotel in Chemnitz.

The aesthetic of the 90s is absolutely an aesthetic of transformation. Until the pandemic, the biggest event I had ever witnessed was the fall of the Wall in 1989 — something that, as a child, was primarily an aesthetic experience. Suddenly there was all this new furniture in Miami Vice colors and these weird Postmodern shapes coming into my life. People were responding to what they saw on TV. All of a sudden there was this idea that you didn’t need to have functionality or furniture that would last forever. Instead, you were looking at sets — which are disposable, which waste money and space instead of optimizing them. This very strong aesthetic memory is something I now use to speak about political change in general, in addition to showing how a system’s values are embodied in consumer objects. My generation had the Soviet first-day-of-school thing, sure, but we also had a West-German education. But there was no concept of how to educate grown-ups about a functioning democracy, other than through the economic or material reality of this new, hyper-accelerated liberalism. Democracy meant that following a radical version of the market economy would make everything fine. We still see that lag now in East Germany. The West hit like a meteor, and people at the time were just busy surviving in the new system — there wasn’t much backlash or organization from labor unions. The ideology seemed to just roll through, without resistance. And I do see it as the role of my generation to speak about this, now that we’re not just trying to adapt to a new political system and economy.

Photographs provided by the PinchukArtCentre © 2021. Photographed by Maksym Bilousov.

How do you feel about generational discourse more broadly? Does how we talk about “millennials” and “Gen X” and “Gen Z” resonate with you? Assigning the same generation to someone born in 1984 and someone born in the early 1990s seems so insane and lacking in context to me.

And we both know it’s not really the same decade everywhere at a given time — things came later to East Germany. But I do feel part of a certain age cohort, let’s say, one I would define as having lived an analogue/digital double life. I think that’s a parallel to the East/West binary, and maybe why you and I have as much overlap as we do. And that digital experience maps onto a Western liberal paradigm in which art comes from within yourself as self-expression, or is generated somehow outside of the system.

I’m still appalled by the mythology that lingers about art somehow existing outside of capitalism, even offering some type of solution to it, when it’s the most luxury product ever. Does that willful lack of awareness in the art market have something to do with why you are drawn to furniture and domestic interiors instead?

My grandfather was a painter in the GDR, which made for a very different relationship to the nature of art and who and what purpose it serves. I try to create spaces where people with different generational or cultural backgrounds can meet and share experiences, even if those experiences are not identical. That’s why the layers are so important — they create different points of access. Everybody knows furniture, and everybody has something to say about it. Whether they find something ugly or beautiful or nostalgic or traumatic in it, there’s always an emotional response and an opinion. You can obviously bring in aspects of theory to be decoded, but furniture, to me, belongs to public, political memory.

For Munich’s Haus der Kunst, Naumann presented Ruinenwert (2019), an exhibition which directly references the architecture of Hitler’s Berghof residence.

It also considered the fascist origins of the museum, which opened in 1937 as the main instutition for Nazi-approved art. In 2021, Naumann presented Einstürzende Reichsbauten at Kunsthaus Dahlem, which is housed in what was once the state-sponsored studio of Nazi sculptor Arno Breker (below). The exhibition’s title — a pun on the Berlin noise rock band Einstürzende Neubauten — means “Collapsing Reich Buildings,” and the installation presented institutional funishings from the Nazi era alongside late-80s GDR souvenirs and PoMo motifs.

In the GDR especially, right? Since there was a lot of standard-issue design.

Even when I’ve done work that incorporates a reference like that, people see things in it that I hadn’t noticed myself. In Korea, when I showed work I did about the divided Germany, I knew it would be discussed in terms of the Korean separation. When I showed in Moscow, my whole construction of “I’m from the East” didn’t work — from the Russian perspective, I’m from the West. But at a simultaneous exhibition in Ukraine, there was a very emotional discussion about the work, and nobody saw it as being about Germany. They saw it as being about them. The work constantly communicates in ways beyond what I initially imagined about why I was producing it, and what narratives I was creating — the meaning that comes to it is completely uncontrollable to me, in a good way. That’s when things take on a life of their own. My process begins on eBay classified ads, where I spend hours looking at people’s furniture and the pictures they take of what they are trying to sell. I read and research a lot as part of my process, but I really start to create the language to express a certain idea in an installation by looking at what people do, at how they post their furniture — usually on my phone.

The lives of objects are the lives of others, right? That’s a GDR narrative of surveillance. You’re on a device, but you’re also in people’s living rooms — amid their most personal and relatable possessions. I mean, it’s so fascinating on eBay when you see someone’s hand in a photograph, or when you can see parts of the house — it’s very, very intimate. And it’s omniscient. It’s the rats in the White House, the guy listening to your private phone calls. It’s you, looking into the American living room through a screen. I started looking at your work during lockdown, entirely on the screen. I think your work translates so well digitally, which is unusual for installations of this scale. But maybe it’s the mediated context of your process that allows the work to translate, as it’s carried through screens or filtered through individual or social experience. As you say, even your own experience of the work seems to change according to how it is viewed, not just by others, but by you.

Even this conversation is mediated through Zoom, and I can see your living room through a screen! But seeing a picture on the Internet is a very unique kind of access. And different types of access — physical, visual, conceptual — and what they add up to are what make an artwork stick with people. I come from a background of film scenography, so I always have this camera view in mind: I want to make sense of every angle, conceptually and literally.

Photographs provided by the PinchukArtCentre © 2021. Photographed by Maksym Bilousov.

So the removal creates a counterintuitive intimacy and insight, and inner experience is a channel through which you get to a community one? I think this connects to what you said about inhabiting a kind of in-between system, and to how you approach interiors from an outside perspective and vice versa. We agree that art as we know it doesn’t exist outside capitalism. But can the artist create the same degree of productive removal in observing the art world — as you do, say, by mediating and staging the political systems you narrate through furniture or set design?

Well, the work I do is not exactly easy to sell. It’s a great idea to work with a medium that is more like set design, where you aren’t expected to create a valuable object, if you don’t ever want to sell anything! But there is a whole process of physical and intellectual labor involved that must be compensated. German museums often don’t pay fees, the idea being that the exhibition increases the artworks’ value and exposes them to collectors who will then buy them. In the East German and Soviet systems, art wasn’t sold to collectors, but it did have to be produced for a social or political purpose — which meant you ended up with something that wasn’t fully art either, because the conditions under which artists made it were based on a decision to function within just another system.

That, I posit, is another lie: the concept of creative freedom, or frankly of freedom in general, at least as the Anglo-Saxon, Protestant system markets it in both America and Germany. You have censorship under one regime, while under the other you have to create a commercial product and pretend it’s the result of experimentation — or worse, “true” self-expression. Neither system encourages that, but only ours pretends to, which to me is the greater insult.

With political systems, it’s important to operate by really going into them. How do you maintain a labor-intensive practice that is not very commercial while still operating fairly as an artist? You can make sure you don’t pass on structures that are wrong and unfair. You can talk about how your assistants need to be paid during endless budget discussions — but you are having them, of course, from within the system. I don’t want to stand in a spectator position on this moral plateau of the political artist looking down. You can’t remove yourself from those dynamics if you want to be a part of society or want to show the world in its complexity — which includes acknowledging how we are all complicit in everything.