The Pocono Palace Resort campus with Lovers’ Lane road sign. Video still, 2024, Nora Chellew.

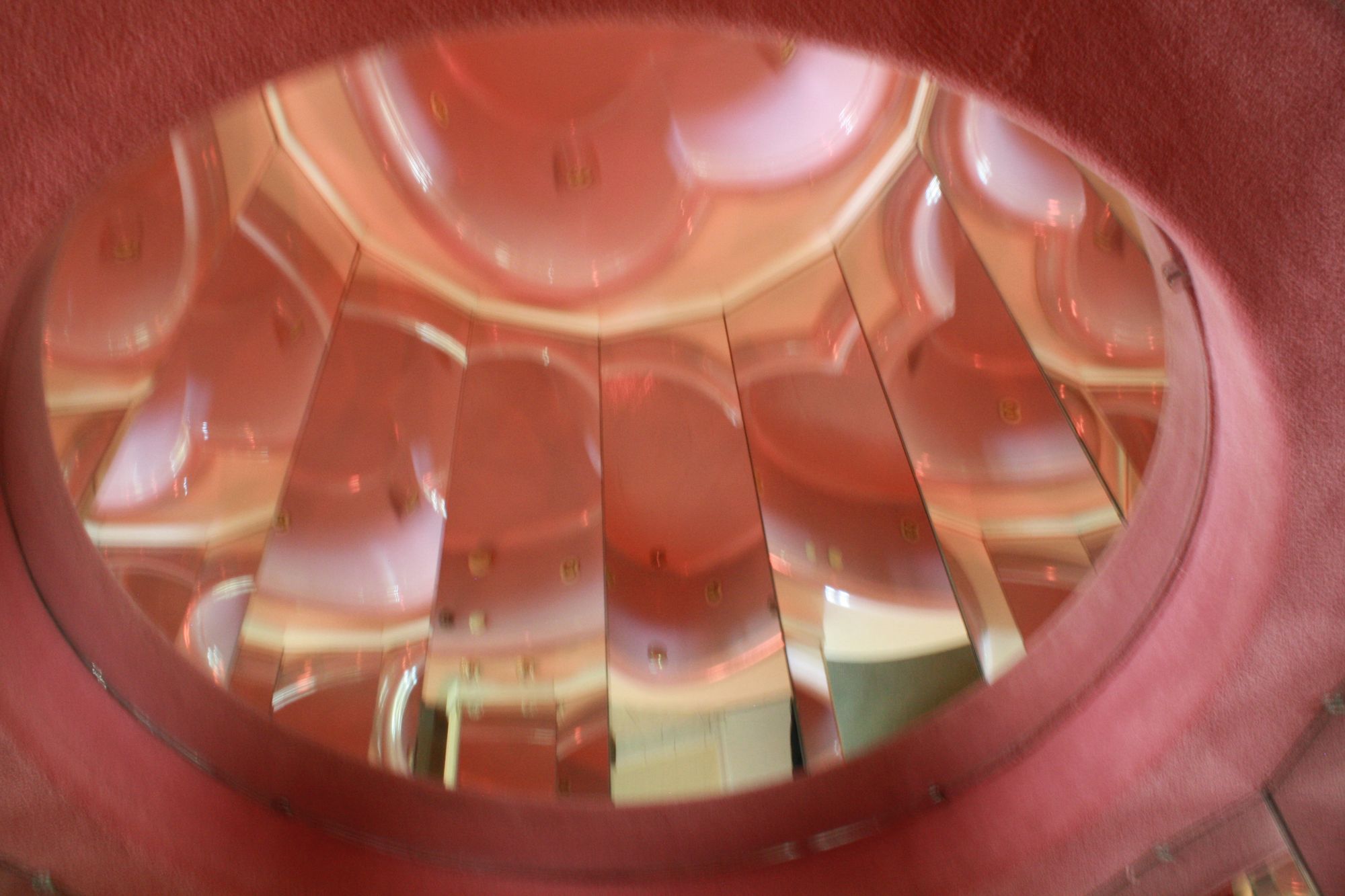

A red heart-shaped tub in the Pocono Palace Resort. Digital photograph, 2024, Nora Chellew.

A crystalline knob squeaks on, spouting water into a glossy, heart-shaped tub. Around you, ceiling and wall mirrors gamefully catch each other’s reflections. Sun shines through the rock-rooted trees outside your window and lands on the edge of your bed’s circular duvet. From your bubble bath vantage, you can make out a few small cabin structures beyond the thicket, seemingly empty. Your suds decompress and fade in tandem with the fizzy wine in your flute. You slip out of the bathwater and onto a spiraling path of soft steps — the architectural lovechild of a grand staircase and an approachable suburban carpet. Welcome to the hub of the American honeymoon boom of the late 20th Century: welcome to the Pocono Mountains.

While the Pocono Mountains and the concept of honeymooning are now wedded in my mind, I first knew the Poconos as a woodland. From ages 8 through 17, I spent summers there. I started campfires with blueberry twigs, flipped capsized canoes, and backed away from large animals slowly. I learned that the rocky, somewhat unforgiving Poconos landscape was formed by ancient glaciers. As I transitioned into adulthood, comfortably acquainted with the craggy ecology, I realized I could not make sense of one mountain species: the honeymoon hotel. I often passed the Pocono Palace Resort, formerly in operation at 206 Fantasy Road, boasting cabaret singers on its marquee. I wondered if the resort’s amorous intentions were out of place in the woods until I realized it was not alone. There was a constellation of couples’ hotels throughout the mountainous landscape, harboring hopeful romantics in heart-shaped tubs.

The Pocono Palace Resort campus with Lovers’ Lane road sign. Video still, 2024, Nora Chellew.

Wedding archway above “Echo Lake” at the Pocono Palace Resort property. Digital photograph, 2024, Nora Chellew.

Welcome sign at the front of the Pocono Palace Resort property. Digital photograph, 2024, Nora Chellew.

In 2020, to satiate my curiosity, I poked around the outside of the abandoned Penn Hills Resort, roughly eleven miles from the Pocono Palace. The ruins of the resort appeared ancient, as if recently recovered in a university-funded dig, rather than simply neglected in the early 2000s. I saw crumbling facades climbing with ivy and crown-shaped signs too painted-over to be useful. One red heart-shaped tub sat out in a patch of grass, cracked at the edges. While there was no water inside, I was delighted to find a full bottle of fruit-punch-flavored Gatorade, perfectly camouflaged to the tub’s cherry red. Most of all, I was thrilled to finally understand the weight and size of a heart-shaped bath — my body in relation to its dual-figure design — but I still had questions. I found answers in the words of architectural historian Barbara Penner.

Penner’s writing filled in gaps in my understanding and had me nodding along with shared inquisitiveness. Her texts take readers through the evolutionary timeline of Poconos suites in relation to the broader history of honeymooning in the United States and Canada. I was lucky enough to speak with her in 2024 about her research, after she kindly responded to my cold-email request for an interview.

In the early 20th Century, I learned from Penner, honeymooning became an increasingly common endeavor, in tandem with expanding transportation options: white, heterosexual couples outside of the upper class were able to partake in the post-marriage practice without breaking the bank. Inns and lodges sprung up in places like the Pocono Mountains to meet the needs of these new newlywed consumers. In the 1950s and early ‘60s, prior to the incorporation of heart-shaped tubs, mountainous honeymoon suites were quaint cabins, built as temporary pseudo-homes for those who had tied the knot before age 21.

Photo of a swan at The Farm on the Hill from one of Anne Vitable and Joseph Chellew’s wedding albums. Digital scan, 2024, personal collection of Nora Chellew.

My grandmother Anne and grandfather Joe fit that exact bill, having married at the ages of 19 and 21 respectively, and subsequently honeymooned at The Farm on the Hill in Swiftwater, PA, “the first dedicated newlywed resort in the Poconos.” Though they divorced years later, their 1951 black-and-white Kodak album tells the story of a charming trip, surrounded by lakes, trees, and sweet cottage structures. In their developed photographs, I recognize the alpine streams and shrubbery I have come to know.

Anne and Joe settled just outside of Philadelphia, so driving to the mountains made all the sense in the world for them. The geographical convenience of the Poconos to major East Coast cities played a part in its success as a honeymooning hotspot. There was another, more complex lure at play as well: The Poconos’ most enticing newlywed offering was security. Postwar husbands and wives on the cusp of their twenties found themselves outside of their parental enclaves for the first time, in an entirely new and entirely adult situation. The Poconos offered guidance through instructive architecture and playful activities. There were private spaces in which couples could test their homemaking skills and public spaces in which couples could connect with other nervous newlyweds. What the Poconos hotels initially failed to do was make these structural guardrails available to all. The Farm on the Hill, for example, opened in 1945, over a decade before the end of Jim Crow-era racial segregation. The homey balm the Poconos used to salve marital worries was exclusionary — by and for white Americans — even as it made honeymooning accessible for wage earners.

In our conversation, Penner describes this resort environment as both alluring and strict:

The suites were embedded in larger resort complexes. The reception is really like a kind of panoptic point. You can't access your room without going through reception. It's one of a series of controls that surround this space to make it safe and to exclude elements that don't fit. It's highly controlled with very strict boundaries. And I would argue that this sense of being in a secure environment was just as important to the allure as any specific offering.

As Poconos honeymoon hotels became more inclusive in the later half of the 20th Century, their scope of safety evolved. That is to say, they did not become any less methodical in their offerings, but rather shifted focus from the domestic to the sensual, offering safe-play services to a wider clientele. In her writing, Penner describes the modern romance hotel structure not as rigid and falsifying, but rather as a scaffold in which authentic experiences are possible.

A transparent floor showing a small pool three levels below in the Pocono Palace Resort’s Fantasy Apple Suite. Digital photograph, 2024, Nora Chellew.

By the mid-1960s and ‘70s, coziness was important to honeymooners, but it wasn’t enough. Couples were tying the knot at an older age, and lovers were more interested in sex than homemaking. It was around this time that Poconos hotels gave themselves an interior makeover worthy of the silver screen. Cabins were retrofitted or rebuilt to house lavish bathing vessels in movie-set designs. Morris B. Wilkins, a famous Poconos hotelier, invented and incorporated heart-shaped tubs into honeymoon suites starting in 1963. This sculptural and functional attraction was sequeled by its sibling, Wilkins’s champagne tower tub, twenty years later.

Penner cites the design strategies of resort architect Morris Lapidus as an influence on Poconos suites. Lapidus wished guests to experience multiple levels within their suites, providing opportunities for grand entrances or exits at every turn. Everything was a step down or up, rounded and open. If you are going to present guests with a premeditated environment, why not have it reflect an actual stage?

While much of the Hollywood architecture now embedded in Poconos hotels feels aesthetically out of sync with their cottage exteriors, the theatrical interior design arguably emphasizes narrative guardrails that mark the space for romance. For instance, a celebratory check-in experience that leads you to a private cabin pairs nicely with a mirrored ceiling and rougey red interior design. The conceptual and the actual complement each other, creating a singularly strong framework for amorous activity. The kitsch disrobes the space of any homelike quality, setting the scene for an experience beyond the norm.

A closeup of a spout on a heart-shaped tub and a mirrored reflection of trees outside at the Pocono Palace Resort. Film photograph, 2024, Nora Chellew.

Blurry photo of a carpet-lined ceiling mirror above a pink, heart-shaped tub at the Pocono Palace Resort. Digital photograph, 2024, Nora Chellew.

Self portrait in reflective glass in a Roman-style suite at the Pocono Palace. A champagne tower tub is visible in the reflection, against a heart-shaped pool. Digital photograph, 2024, Nora Chellew.

The hot-and-heaviness of the Poconos honeymoon business increased in temperature into the 1980s until, supposedly, hotels were offering video cameras to guests. The shine and shag of the suites moved beyond the institution of marriage and into a world of noncommittal couples. Splashy bubble bath advertisements promised climactic experiences to couples or solo travelers. These conceptual changes, promoted by magazine spreads, drummed up business that was beginning to die. The new hyper-hedonistic focus did not distort the camp (as in kitsch) interiors or camp (as in campground) exteriors of the resorts. It did, however, mark these resorts as pornographic spaces. This may be the reason why some contemporary travelers view these spaces as tawdry: it is as if the Poconos style of romantic kitsch has become synonymous with a certain vulgarity. Penner addressed the unfair reception of this aesthetic in our conversation, stating:

I honestly felt like there was no language to sympathetically engage these kinds of spaces… People take [heart-shaped tubs] as a kind of offense against good taste.

At present, only two honeymoon hotels remain in operation in the Poconos, through the Cove Haven group. Cove Haven’s former third property was the Pocono Palace, which closed in 2024. Thanks to the lovely staff members of Cove Haven, I was able to photograph and videotape the Pocono Palace a few days before it closed. I tried to capture some of the romance and ritual soaked into the suites. As these Poconos properties disappear, I think about the methods and meanings of enshrining this amorous architecture. In our discussion, Penner and I imagined a reality in which the Smithsonian acquired a heart-shaped tub. We agreed it would be an amazing addition to their collection, though she noted that, “We shouldn't rely so much on official institutions to curate our collective memory.”

The adaptations and renovations that took place in these Poconos love resorts plot cultural attitudes and historical precedents at the scale of the human body. Their seismic shifts serve as records of the history of American romance: we can no less forget their impact than that of the Arctic glaciers responsible for Pennsylvania’s rocky terrain. And, if we choose to remember, I believe that the medium matters. Perhaps it’s because I operate in the fields of sculpture and live art that I don’t think images do these properties justice. We need to map, measure, and mold the transformations of these sunken rooms and raised baths, following the breadcrumbs of the sprawling woodsy campuses. To understand all that has transpired, we must hold our bodies against the duetting designs.