Inside Hajime Sorayama's studio. Photo courtesy of NANZUKA.

©Hajime Sorayama. Courtesy of NANZUKA. Photo by Kazushi Toyota.

Dynamic Visual Acuity, or DVA, refers to the ability to identify details of an object when there are movements between them. DVA is handy in activities such as driving or ball sports, when the subject needs to quickly dodge or catch something. “I have an antenna to catch sexy things,” Hajime Sorayama says. “For example, you stare at a handsome guy when you walk down the street — that’s DVA.”

Sorayama is sitting in his apartment-turned-studio in Gotanda, Tokyo, surrounded by the chaos of his art pieces and paraphernalia he’s collected since he began renting the space over 40 years ago. His signature fembots stand alongside mounds of old Disney toys that spill over the shelves and onto his two working desks. Print-outs of references — anatomical diagrams of human bones and animal body parts, illustrations of sex positions — hang above Sorayama’s head, hooked on two fishing rods like laundry waiting to dry. On the ceiling of the narrow hallway between his main workspace and kitchen is a life-size illustration of an armed, naked woman showing off her devil’s tail and vaginal piercing. With Sorayama, the disorder seems natural; it’s the result of his adult life accumulated in material layers, like beach sand slowly piling upshore. “I tend to collect things I haven’t seen before. I find many things erotic,” Sorayama says with a grin.

Inside Hajime Sorayama's studio. Photo courtesy of NANZUKA.

Inside Hajime Sorayama's studio. Photo courtesy of NANZUKA.

He walks to the back room of his studio, excited to show me his iguana Zunda, named after the Japanese mochi dessert. It has been dead for nearly two decades, but Sorayama preserved its body. He rummages through a pile of Bearbricks and other trinkets before he finds its three-foot-long body covered in dust. “I snuck it in the house one day, but my daughter caught me stealing vegetables from the kitchen to feed it,” he says. When asked if he’s had any other pets, he jokes that there are many onee-sans, or ladies. “I feed them cash.”

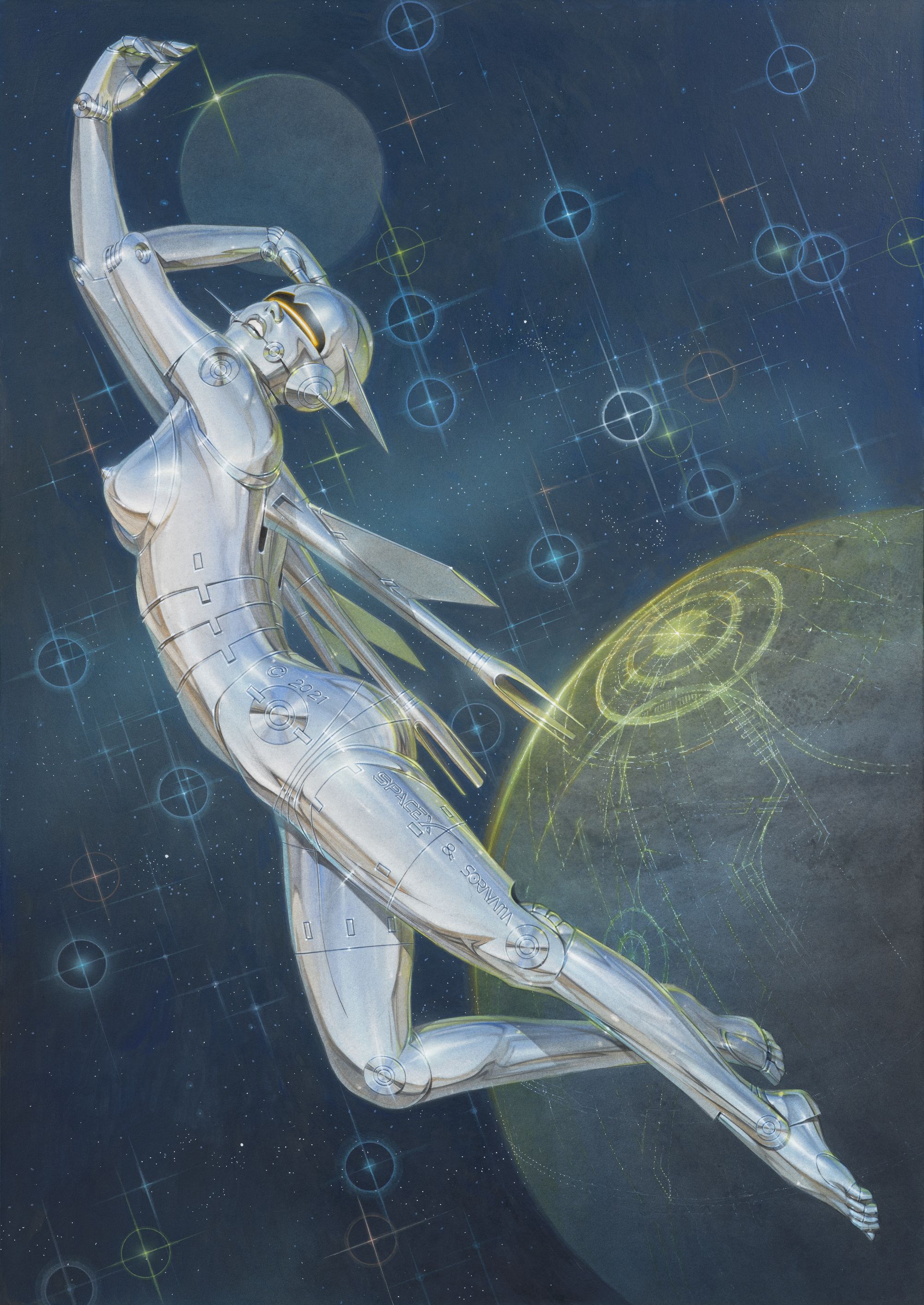

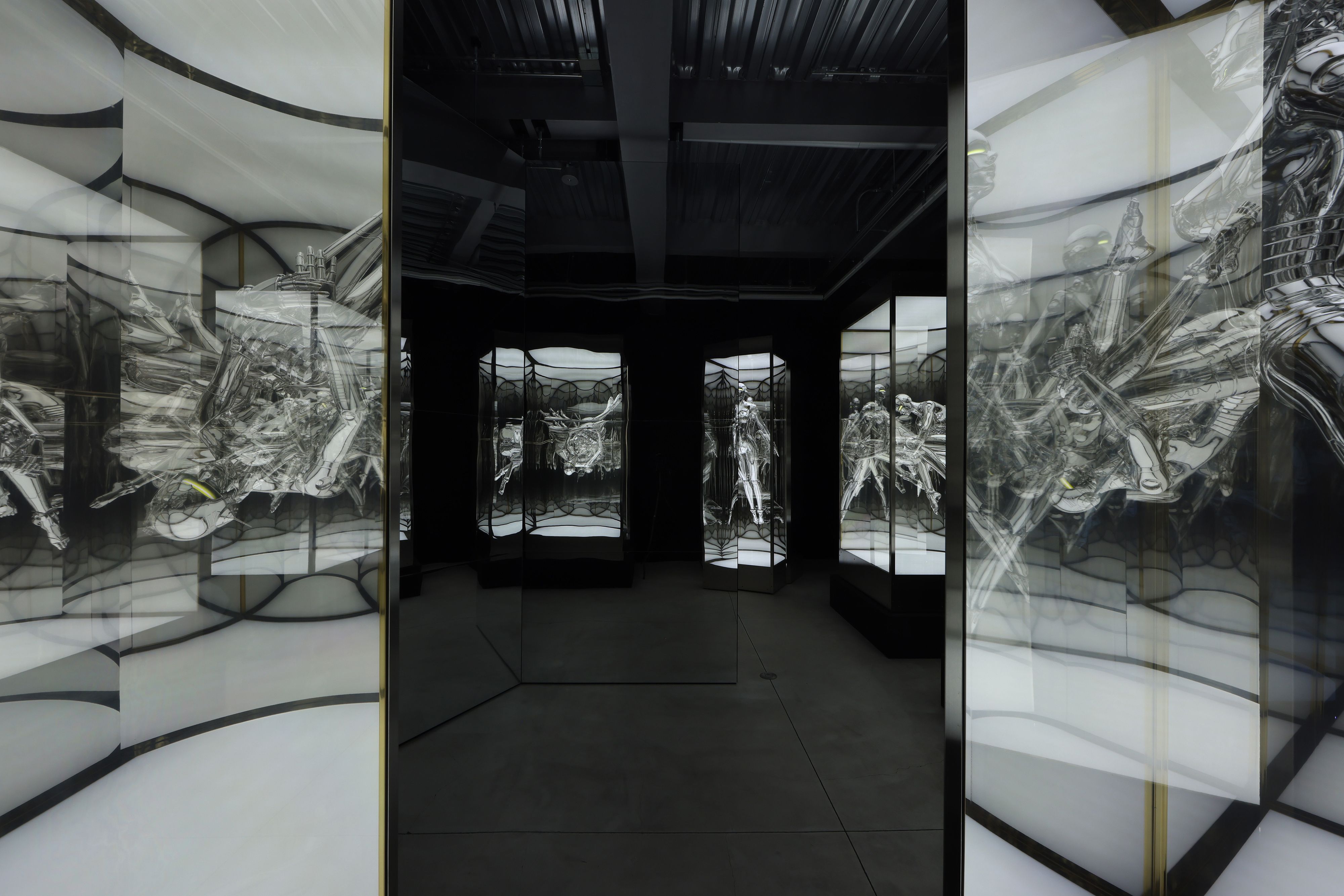

He had just wrapped up Space Traveler, his solo exhibition at Tokyo’s NANZUKA UNDERGROUND. Shown in the gallery’s three locations at the same time, Space Traveler featured large-scale paintings and recent additions to his ongoing Sexy Robot sculpture series, which he started in the late 70s. The robots, also called fembots or Gynoids, are the same ones that stood over Kim Jones’ Dior Homme pre-fall 2019 runway and The Weeknd’s 2023 European tour stage. For Space Traveler, Sorayama showcased full-size versions of his famous fembots, totaling up to eight feet tall. One figure in bronze stands heroically, looking up with her arms spread wide as if in mid-flight. Another is encased in a plexiglass infinity room, suspended upside-down in the air. Sorayama’s paintings show the same Gynoids floating through space, or iconic figures such as Iron Man, Marilyn Monroe, and Elvis Presley as the same kind of silver-skinned robot. “People who are obsessed with Sorayama’s work are so attracted to the futurism, but it's our imagination that he’s really into space,” says Katy Murata, one of his agents at NANZUKA UNDERGROUND. “From his view, he just makes what he likes.”

Hajime Sorayama, Untitled, 2020; Acrylic on illustration board, 28.6 x 20.2 in.

Hajime Sorayama, Untitled, 2018; Acrylic on illustration board, 28.6 x 20.2 in.

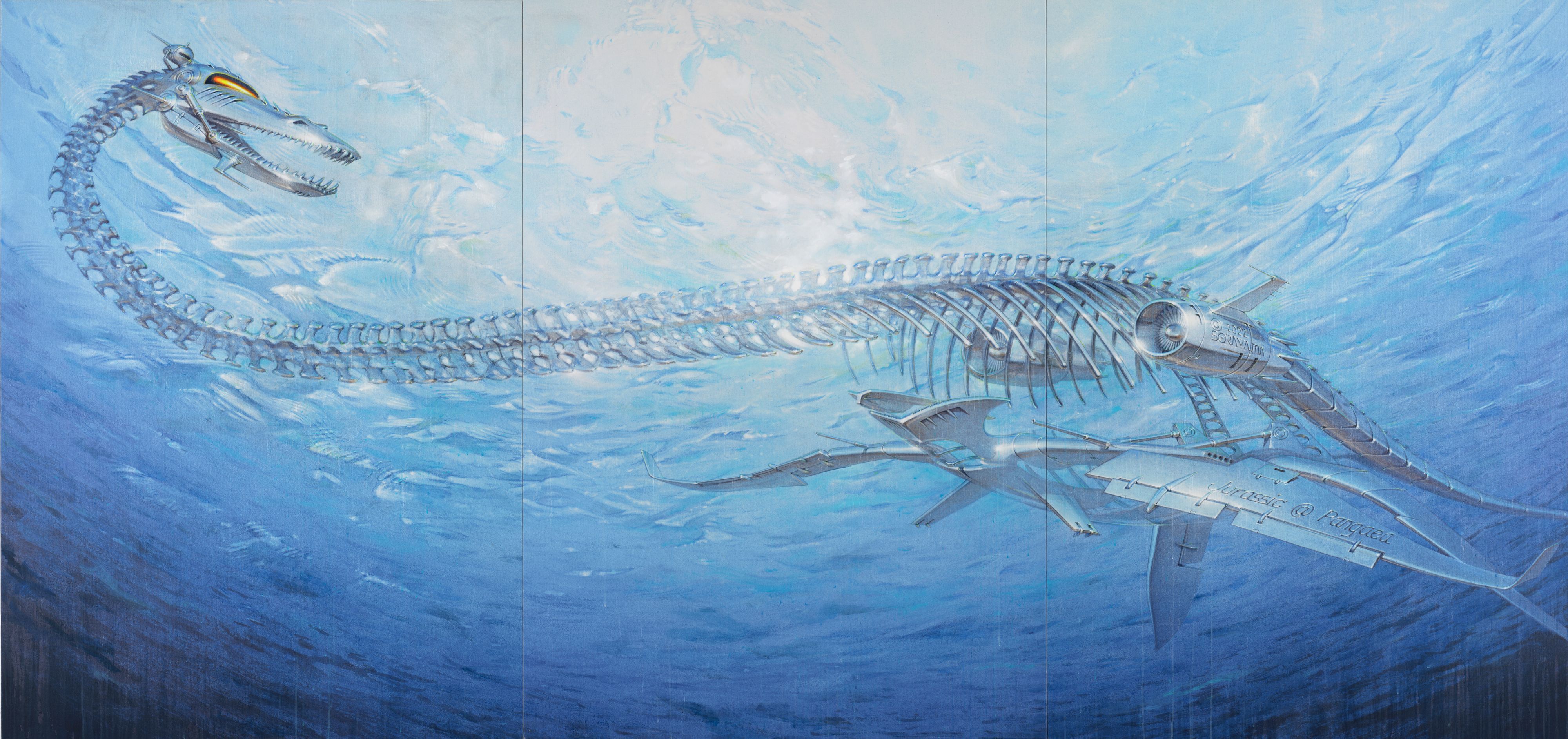

The concept of space travel interests Sorayama, but only as much as it intrigues other people. “I have no particular intention to connect to the future or air space or anything,” Sorayama clarifies. “Space, or things like dinosaurs, cars, the military — for men, these are eternal idols. Boys in general have interest in these things. I just never got out of that.” He playfully scratches his head. “I’m still in kindergarten.”

What the 76-year-old artist does like, however, is challenging taboos. “Feminists and fundamentalists tend to attack me, but they don’t understand or relate to the deeper meaning in my work. It’s a high-level, academic conversation,” Sorayama explains, his expression quickly turning serious. He points to a five-foot-square painting across the room, depicting another giant Gynoid kneeling and tilting her head back as another robot licks her vagina. She has perfectly curled blonde hair, in the style of a 50s Stepford wife. Her left nipple is pierced with the ankh, or the hieroglyphic for “life,” and below her belly button are the words Sacer Saccatum, or “holy urine,” etched in Latin. It’s a play on Christian baptism, replacing the sacred act with oral sex. “I feel ecstasy when I trigger people’s anger. I’m testing them,” Sorayama says. “I have more work related to religion that I can’t really publish. I have to wait until the world is able to follow — maybe after I’m dead.”

Hajime Sorayama, Untitled_Sexy Robot_Space traveler 1/6 scale, 2023; Alloy, PU, stainless steel. 17.7 x 13.4 x 11.4 in.

Hajime Sorayama, Untitled_Sexy Robot_Space traveler 1/6 scale, 2023; Alloy, PU, stainless steel. 17.7 x 13.4 x 11.4 in.

Hajime Sorayama, Untitled_Sexy Robot_Space traveler, 2022; Fiberglass reinforced plastic, UV curable resin, plexiglass, chrome spray, light-emitting diode, stainless steel, steel. 98.4 x 48 x 50 in.

Hajime Sorayama, Untitled_Sexy Robot_Space traveler, 2022; Fiberglass reinforced plastic, UV curable resin, plexiglass, chrome spray, light-emitting diode, stainless steel, steel. 98.4 x 48 x 50 in.

Years ago in an interview with Japanese broadcasting network NHK, Sorayama was asked to name the 100 most excellent human inventions. He cited religion as the first one. “In my world, I’m my own god,” he says. He considers his Gynoids goddesses, his precious creations, rather than mere robots or sexual objects. As a boy, he worshiped the beautiful women in Playboy pin-ups, a lifelong fascination that continues to fuel his work. “I opened my eyes to sex when I was born, since I was sucking my mother’s breast. Sex is always at the core of everything, of our desire to live. For example at a concert, the vocalist is always at the center, so maybe he plays the sexiest role. Mick Jagger is 80 years old, but he’s sexy, right?,” he asks, peeking through his glasses.

It’s a hot, wet summer day in Tokyo, a simmering 95 degrees and pouring rain. Sorayama offers iced rooibos tea from a mini fridge. He is wearing a white Hawaiian shirt with a big, blue floral pattern, and matching blue plaid shorts. Despite the dynamism in his work, he maintains a calm air about him, punctuated by occasional bantering. “I have no strength anymore,” he says. “I don’t like going abroad or to opening receptions. My face muscles hurt from having to smile.” In reality, Sorayama hasn’t been able to travel for the last five years due to problems in his right ear. He claims he will never be able to go to his international exhibitions again.

Hajime Sorayama, Untitled, 2022; Acrylic, digital print on canvas, triptych 77.5 x 164.4 x 1.6 in.

Sorayama grew up in post-World War II Japan in Imabari, a small industrial town known for its shipbuilding, towel production, and chicken skewers. His father was a carpenter, and his mother a sewer. “Because of my parents’ occupation working with wood and fabric, I felt [those materials] were under my control, but I have an inferiority complex toward metal,” he says. “It was beyond my environment.” At around age 7, he would stare at the small factory across his street, where a neighbor brazed metal for a living. “He thought I was weird,” recalls Sorayama. “I loved how shiny it became after brazing. I would look at it for hours and hours.” As a child, he dreamed of becoming a sword craftsman, shrine carpenter, and pilot.

The artist maintained his curiosity through college. At Shikoku Gakuin University, a college two hours away from his hometown, Sorayama was expelled in his second year for founding Pink Journal, an explicit zine. “There was nothing, no culture in that place, like a countryside without oxygen. I was really bored,” he says. He moved to Tokyo to transfer to Chuou Bijyustu Gakuin, and switched his major from literature to graphic design. The year was 1967, before the time of computer graphics. While claiming that he “has no teacher,” Sorayama names the late German industrial designer Luigi Colani — known for his round, bulbous shapes in 50s sports cars and furniture — as one of his favorite influences. “His curved shapes were far from practical. They were more fantasy,” he says. “I don’t like architecture because it has to be practical. For me, commercial art and fine art are the same.”

©Hajime Sorayama. Courtesy of NANZUKA.

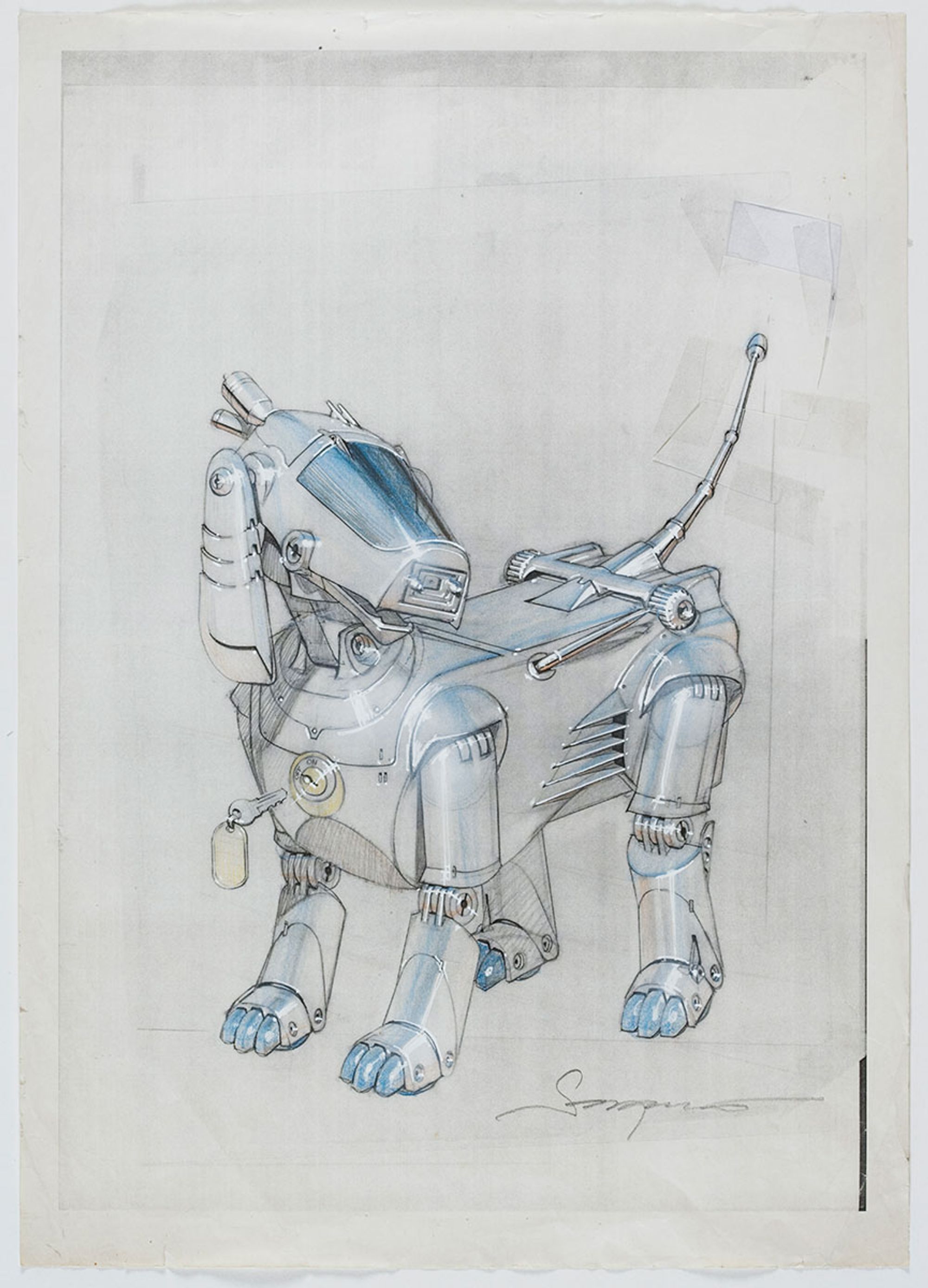

Within a year, Sorayama graduated and began working at an advertising agency, going on to freelance in 1972. He drew his first robot in 1978, when George Lucas commissioned him to ideate a character inspired by Star Wars’ C-3PO. One of Sorayama’s most talked about projects to this day is his design for the 1999 Sony AIBO, the world’s first pet robot. What excited him about making the mechanic dog was not the product itself, but the team involved. “There were people from MIT who graduated skipping a grade, those very capable, super geniuses. I wanted to interact with them,” remembers Sorayama. “The scale of the project was small, but for me, I felt the same excitement as NASA going to Mercury.”

Shinji Nanzuka, founder of NANZUKA UNDERGROUND, attributes Sorayama’s penchant for collaboration to his background in graphic design. “Sorayama originally worked in the commercial art field, which means he worked for the client,” Nanzuka says. “For him, it’s totally natural to collaborate with brands. He’s very happy to build partnerships.” Sorayama has had an especially successful track record in fashion, collaborating with brands such as Dior, Thierry Mugler, Roger Dubuis, Bvlgari, and more. His work has been hailed around the world as being among the most representative of Japanese modernist and futurist art, a truth both Nanzuka and Sorayama find ironic. “We didn’t really understand why the robot represents Japanese culture for Western people. This is an asset of old Japan, when we had good tech companies in the 80s and 90s,” Nanzuka explains. “But I guess it’s good to know we can be proud of it.”

Hajime Sorayama, concept design for AIBO, 1997; Acrylic on illustration board, 11.7 x 7.8 in.

Hajime Sorayama, AIBO, 1999; Plastic, battery. 10.5 x 10.8 x 6.14 in.

At the core of Sorayama’s work is the artist’s longing to transcend reality. His uninhibited, graphic eroticism challenges our sense of propriety by reflecting our most primal desires back to ourselves, and pokes at societal and moral conventions. To conclude his work is simply erotic or futuristic is reductive; whether Sorayama intends it or not, his Gynoids ask what really makes us human — is it our instincts, our actions, or something else? Their placement in space catapults us to a world of fantasy, where those questions are rendered futile. “I want to create something that has never been done before, that doesn’t exist, and which cannot be replicated. My life’s work is to materialize [these ideas],” Sorayama says.

When asked what his family thinks of his work, Sorayama shakes his head. “They are ashamed by what I do of course!,” he exclaims theatrically, as if he gets pleasure from this fact. He tells a story of when his daughter was in kindergarten, how she used to hide his heavy art pieces before bringing friends over. “Her friend Ai-chan told her parents that I had ecchi things,” he says, referring to the abbreviated Japanese slang for hentai. “But major collaborations with Dior and Bvlgari, they can accept.” He gestures the okay sign with his hands.

Installation view of Hajime Sorayama's Space Traveler at NANZUKA UNDERGROUND. Photo courtesy of NANZUKA.

Next on Sorayama’s agenda is a new artbook set to release, a massive, comprehensive tome of his archive. He’s also the inaugural artist to open a solo exhibition for the new Museum of Sex location in Miami this month. In his downtime, he likes to go sailing with “his boys,” a group of ten best friends collectively called Zokuzoku, because they get goosebumps on the yacht. “My wife gets seasick, so I can invite all the women and do bad things!,” Sorayama jokes.

He puts on his slippers and returns to the back room of his studio, bringing back four large, elongated metal globs on a plate with another half dozen smaller nuggets. Sorayama fixes his glasses and explains they are his feces from 50 years ago. “I shat on newspapers and plated them,” he describes. “I had to try three times before finding the perfect shape.” Sorayama is still trying to create his most perfect work of art. “My newest work is my masterpiece now, and my next one will be my most representative piece,” he says. “It’s an ongoing process until I die.”