Precast rammed earth systems for the Backyard Community Club, Accra, Ghana. Image courtesy of DeRoche Projects.

Glenn DeRoche photographed by Christian Saint.

Glenn DeRoche is an architect of stories. For the last 15 years, the Brooklyn-born designer has wielded light, shadow, material, and texture to create sensitive and critical displays of myth-making across multiple contexts and continents. Straight out of his undergraduate degree in 2010, DeRoche started working for Adjaye Associates, where he remained for a little over a decade. In the space of those years, he assumed the Project Director role at the studio’s London office, leading its projects across Africa while earning his Master’s at The Bartlett School of Architecture. In 2019, he relocated to Accra, Ghana, where he began his professional collaboration with lecturer and fellow architect Juergen Benson-Strohmayer. Together, they designed the Holcim Award-winning Surf Ghana Collective space in Busua on the western coast of Ghana, a photography art gallery in Vienna, and a number of projects with the Ghanaian painter and visual artist Amoako Boafo. Now a solo act under his own namesake firm, DeRoche Projects, the ever-sharp architect is out to share his brand of design-by-context as he continues to craft an architectural dialogue that serves as a celebration of heritage, sustainable construction, and community — ideas which are far too often rendered hollow buzzwords within the design world, but here, are the point, the crux, and the action. This fall, in Accra’s Osu neighborhood, the Backyard Tennis Club, a youth-focused community and sports center with an innovative rammed-earth structure that combines all he’s learned about the material and its limitations over the years, is set to open to the public. His recent collaboration with Boafo, I Do Not Come to You by Chance, the artist’s inaugural British solo exhibition and the first of a three-part series exploring space and community, recently closed at the Gagosian Mayfair. With a grand intervention of a blackened-by-fire pavilion that half-fictionalizes Boafo’s childhood home, the architecture is an accordion that folds together moments that speak to collective memory, cultural identities, and artisanal ways of making. When we spoke a week before the show’s closing, DeRoche’s voice hummed through laptop speakers, considered and precise. I got the impression that the guttural sensitivity I feel when faced with his work is less a personal projection than an intentional sentiment that he’s worked hard to imbue each project with. With more large-scale commercial projects on the horizon, plus another immersive, site-specific pavilion for Boafo’s new solo exhibition, I Have Been Here Before, which opened this past week at the Wooyang Art Museum in South Korea, we talked about the journey from photographing Brooklyn’s makeshift basketball hoops to designing a seven-building-big scheme, community-as-listening, and constructing an architecture that we can call our own.

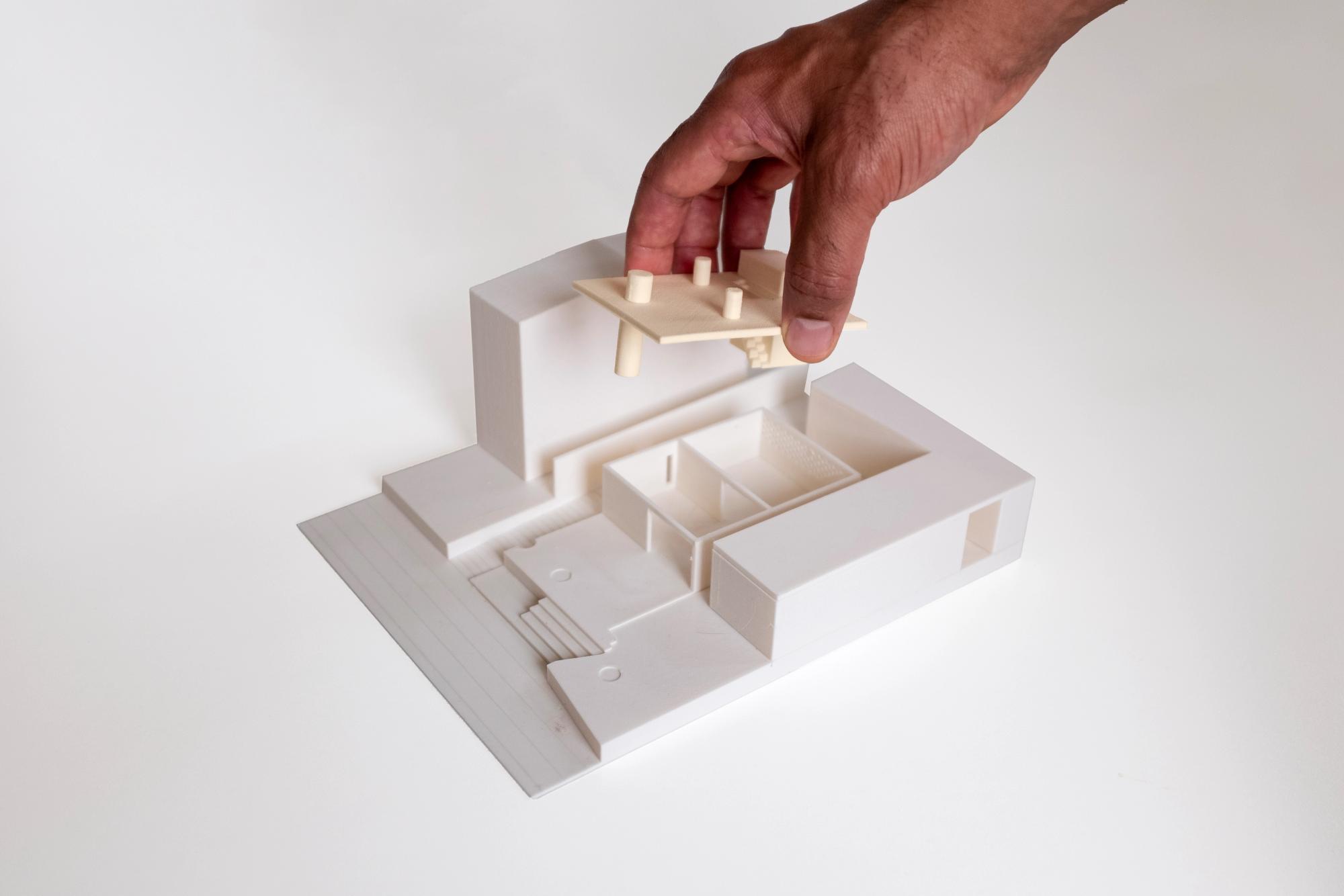

Precast rammed earth systems for the Backyard Community Club, Accra, Ghana. Image courtesy of DeRoche Projects.

The Volta Pavilion by Glenn DeRoche in collaboration with Juergen Strohmayer, at the Belvedere Museum, Vienna. Image courtesy of Julien Lanoo.

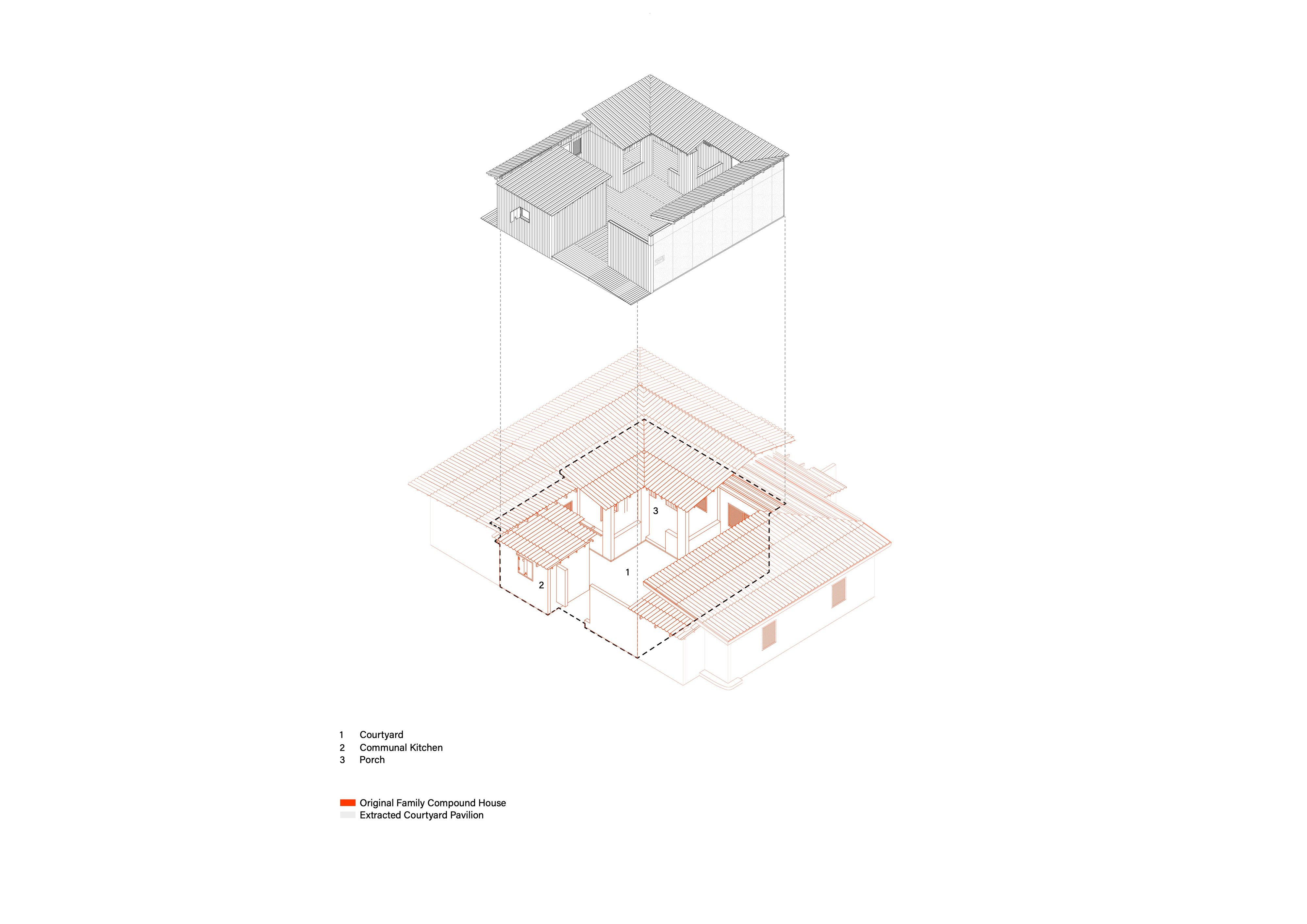

Interior view of the Awulai Ashia Courtyard Pavilion in Amaoko Boafo’s I Do Not Come to You By Chance at Gagosian Mayfair. Image courtesy of Julien Lanoo.

Angel Harvey-Ideozu: Architecture! How did you get into it?

Glenn DeRoche: I got into it by accident. Growing up, I was interested in photography, but coming from a first-generation Caribbean household in America, art was understood as a hobby, not a career. The appropriate jobs were engineer, lawyer, and doctor. To keep the peace, I enrolled in pre-collegiate engineering classes. But with the lack of resources and the level of poverty in Bedford-Stuyvesant, where I lived and went to school in the 90s and early 2000s, I didn’t have the best experience. In my senior year, a guidance counselor recommended architecture as a compromise between art and engineering, and for the first two years of architecture school, I resented them for it. Architecture was too conceptual and broad, and I was really unsure of how to express myself. I didn’t think we were learning good life skills. Everything shifted when I got into a course with Fabian Llonch, who introduced me to thinking about how buildings shape lived experiences and impact people both collectively and individually. I started to see the potential of architecture as a tool for empathy, storytelling, and reimagining spaces.

Has photography come back around in your practice?

It has. When I look back at my photographs from high school, while the content may have changed — I’m no longer taking pictures of graffiti or milk crates fashioned into basketball hoops — I can see many of the same qualities of those images still adorn my work now: that capturing of time, light, shadow, and texture. That’s what architecture really is. I’m obsessed with that.

Clearly! Your work is full of some really intense textural compositions, from the treatment of those behemoth concrete pillars in the Surf Ghana Collective space — that rough-hewn fluting which then leeches onto the ceiling and pushes out to frame either end of the building — to the juxtaposition between the smooth and the coarse, throughout the dot.ateliers | Ogbojo residence in Accra. What’s your relationship to texture?

I see texture as a way of deepening the sensorial qualities of architecture. It allows for depth, richness, and this poetic dance between light and shadow, which create emotive and surreal ways of making and experiencing space. Texture also choreographs narratives and sequences, which is fundamental for me. I use it — especially in adaptive reuse projects — as a tool to tell stories of the past and present. So those pillars and that roof slab cast over the existing room in the Surf Ghana space are textured with raffia palm to identify them as new elements while referencing the pre-existing ficus trees on site. Whether it’s the charred timber in I Do Not Come to You by Chance or the rammed earth panels in our Backyard Tennis Club project, texture guides the eye as well as the body. It marks transitions, sets tones, and makes a space feel lived in and responsive. In a way, it’s another form of language for me — one that doesn’t have to be spoken loudly, but should be felt deeply.

Glenn DeRoche photographed by Christian Saint.

Interior view of the dot.ateliers | Ogbojo Residence by Glenn DeRoche in collaboration with Juergen Strohmayer, in Accra, Ghana. Image courtesy of Julien Lanoo.

dot.ateliers | Ogbojo Residence by Glenn DeRoche in collaboration with Juergen Strohmayer, in Accra, Ghana. Image courtesy of Julien Lanoo.

Model of Surf Ghana Collective by Glenn DeRoche in collaboration with Juergen Strohmayer, in Busua, Ghana. Image courtesy of DeRoche Projects.

Surf Ghana Collective by Glenn DeRoche in collaboration with Juergen Strohmayer, in Busua, Ghana. Image courtesy of Julien Lanoo.

Between interpolating the raffia texture from the Surf Ghana site and extracting and recontextualizing Amoako Boafo’s childhood home for the courtyard in I Do Not Come to You by Chance, it’s almost like you’re sampling through architecture. Tell me about your relationship to music.

I don’t draw or conceptualize work in the traditional architectural sense, but I often use music to channel ideas. Every project starts with a series of keywords that define my ambitions. I’m a very visual person, and music helps me see and think creatively, so during that initial conceptualizing phase — which I often do alone — the interplay between music and those keywords evoke emotion, silence, and reflection, which drives my immediate response. It’s funny that you mentioned music, because I never really thought about it until you asked, but I really do use it and it’s very much a part of the practice. There is always music playing in the studio.

I’ve been drawing a map of your existence. You were born in Brooklyn, have ethnic roots in the Caribbean, worked and studied in London, and now live and work in Ghana. How do you see that interconnectivity play out in your work?

After getting into architecture, I started looking back at New York City and reflecting on how it formed my psyche about building: why we build and who we build for. Growing up in Brooklyn in the mid-80s to early 2000s was foundational for me — when Park Slope wasn’t the Park Slope we know today and Bedford-Stuyvesant wasn’t yet gentrified. There was a certain rhythm and density that taught me how to read space differently: how to navigate complexity and notice what’s improvised, broken, and functioning. On a different note, the Caribbean gave me an early sense of how layered and contradictory places like where we’re from can be, and how beauty and instability often exist side by side: lush landscapes next to eroded roads and sophisticated cultural systems inside colonial leftovers. Those conditions shaped a sensibility and resourcefulness that prepared me for working in Ghana and deepened my relationship to material culture: how things are made and how they’ve been used over time. It also brought about a sense of clarity on my own lineage and how it fits into this larger story.

You’ve just opened a new pavilion in the Wooyang Museum of Contemporary Art in South Korea. That’s your third pavilion. What does the pavilion mean to you as an architectural form or as a social intervention?

As poetic and beautiful as architecture is, it’s also very rigid. If you don’t have the right client, there are practical constraints that can stifle innovation. It can be done and we do it, but it requires a lot more time. Whereas the pavilions are quicker tools of experimentation that allow us to be consistently inquisitive, naïve, playful, and innovative while considering how to upscale ideas. Take the Volta Pavilion in collaboration with Juergen [Strohmayer] and Amoako [Boafo], for example. We used reclaimed petrified timber from the bed of Lake Volta because I wanted to recommend it for a different larger commercial project. Having been in this industry for a while, I understand that when suggesting innovative ideas, the only way to avoid being shut down is to provide precedent. I had to test this wood with the Pavilion in order to make that a reality, which we did.

You’ve spoken about considering a new visual identity for modernity. What does that look like?

[In West Africa] we’re in a vicious cycle of oversubscribing to models of architecture imported from the Global North which, in our landscape, requires extensive non-renewable resources. But that wasn’t always the case. During the era of Tropical Modernism [from the 1940s to the 1970s], for example, architects designed with the environment in mind, responding to light, airflow, and spatial needs in ways that made sense for the surrounding context. But even then, the materials often remained foreign. The prevailing image of Tropical Modernism is beautiful overhangs but it’s all concrete. Concrete roofs and breeze blocks. The local vernacular was an abundant and culturally embedded system, but it was largely left out of Tropical Modernist buildings. For me, a new visual identity is really a renaissance: a return to form-responsive architecture that embraces indigenous knowledge systems and sees technology act not as a foreign overlay, but as a tool to refine and elevate what’s already there. It’s about a dialogue between the past and present, the handmade and high tech, and that’s the approach we’re taking with our Backyard Tennis Club project. If we can use technology to advance traditional building systems, we can begin to define a new modern architecture: one that doesn’t rely on mimicry; one that grows out of the land, its history and innovations, and offers a visual language that’s specific, grounded, and future-facing. A holistic and sustainable architecture within our region. An architecture that we can call our own.

Axonometric drawing extracting the Awulai Ashia Courtyard Pavilion in I Do Not Come to You By Chance from Amoako Boafo’s childhood home in Accra, Ghana. Courtesy DeRoche Projects.

Amoako Boafo’s childhood courtyard house in Accra, Ghana. Image courtesy of Edem Tamakloe.

Installation view of the Awulai Ashia Courtyard Pavilion in Amaoko Boafo's I Do Not Come to You By Chance at Gagosian Mayfair. Image courtesy of Julien Lanoo.

What does community mean to you on both a personal level and a global level?

I’ll start by saying what community isn’t. It’s not a demographic or a targeted audience. It’s a set of relationships. It’s about how people live together, support one another, and shape their environments in real time. Within the studio, community isn't something that we design for but something that we build with. It’s embedded in the process of the work, not just the outcome. I’m especially interested in the informal systems: the networks of care, resourcefulness, and adaptation that communities create to make things work, especially in this region. These often go unacknowledged, but they’re deeply rooted in architecture in that they shape space, behavior, and identity in ways that are powerful and lasting. Community means listening closely and understanding not just what’s needed, but what’s already there. It’s about honoring local knowledge and embracing collaboration, allowing for projects to evolve through conversation and feedback, and not having a fixed idea on what something should be. Whether it’s a cultural space or a public intervention, the goal is to make something that reflects and respects the people it serves, and feels lived in, loved, and legible to them.

Can you talk to me about your relationship with Amoako Boafo?

Absolutely. Amoako is a dreamer, just like myself, so there are often times when it’s unclear why he’s showing a reference or pushing an idea, but he has a very good, critical eye. We have a lot of trust with one another, so it always ends up taking shape. One of the powerful things about working with someone like Amoako is that the collaboration isn’t static. We’re constantly in dialogue and evolving together as visionaries and artists. He has become a very close friend and collaborator, and each project becomes a checkpoint in that shared journey where we get to test new ideas and stretch what we thought was possible.

The latest of those checkpoints explores the relationship between architecture and art. What do you make of the relationship?

Without a doubt, I see architecture and art as deeply intertwined. To me, they’re both about shaping experiences, provoking emotion, and telling stories. The relationship also isn’t hierarchical — where architecture is just a container for art and art is just something to be placed within space. It’s reciprocal. When the two are in dialogue, they can create something immersive that moves people visually, physically, and emotionally. Looking at the courtyard of I Do Not Come to You by Chance, it was interesting to see how the abstraction of Amoako’s family home in Ghana evoked the memory of growing up in a courtyard house for other West Africans. When done well, that is the power of art and architecture.

Precast rammed earth systems for the Backyard Community Club, Accra, Ghana. Image courtesy of DeRoche Projects.

Glenn DeRoche photographed by Moses Kwame Kaydee.

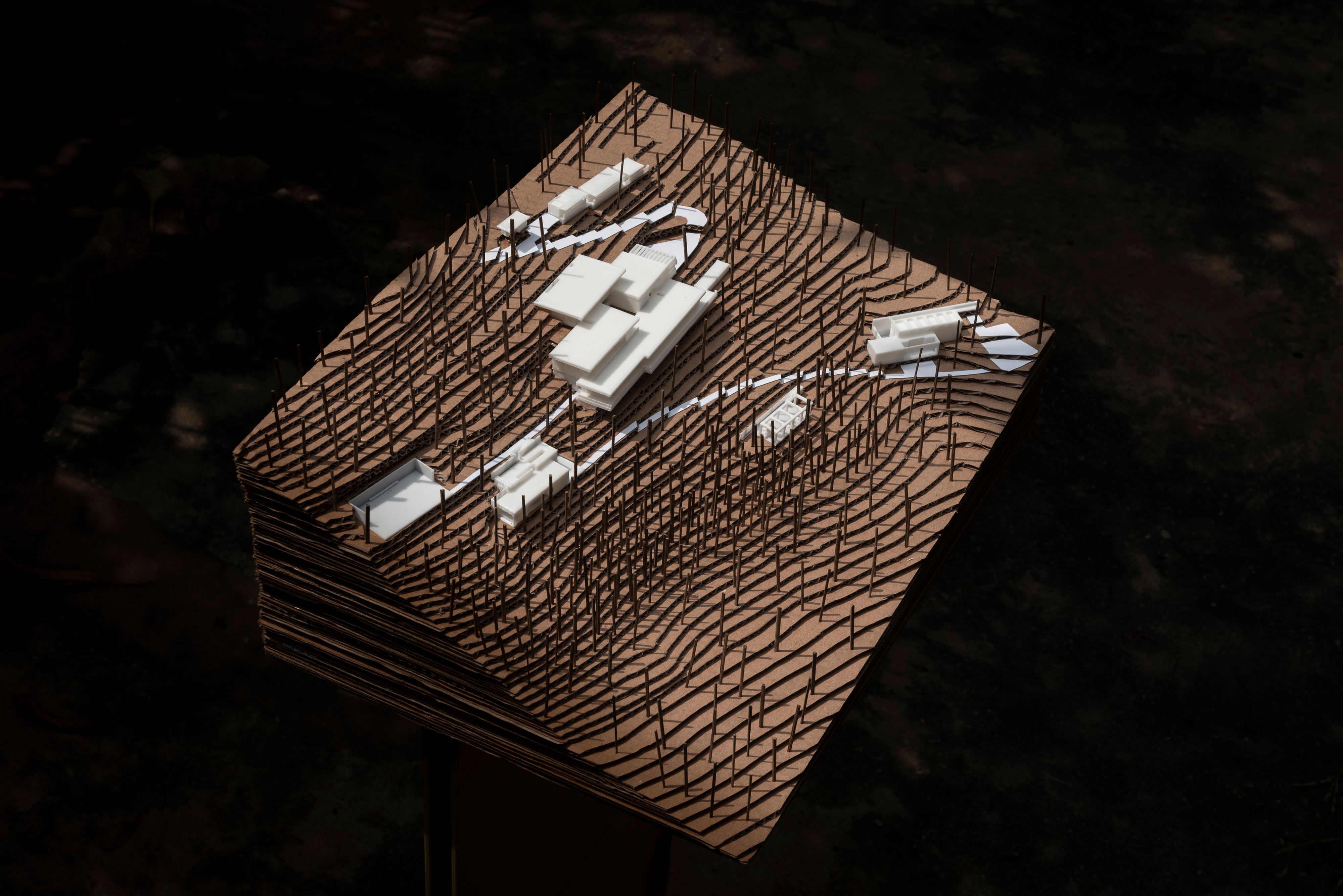

Model of the Aburi Artist Retreat, Ghana. Image courtesy of DeRoche Projects.

Other than the remaining two shows in that collaboration, what are you looking forward to at the moment?

Our first large-scale cultural project, the Aburi Artist Retreat in Ghana’s Eastern region, which is set to break ground by the end of the year. It’s a huge seven-building campus with dwellings, an art gallery, spaces for wellness and relaxation, and a sculpture garden. So far, we’ve only made smaller-scale interventions, so it’s refreshing to have someone take a chance on the studio based on our principles, and want to see our ideas translate to a larger scale. But what I’m really interested in at the moment is hybrid techniques for building, which combine traditional and contemporary methods to create more sustainable architecture that still works within our local constraints. There’s a global shift away from concrete, which I fully support. But in the context of the Global South, it’s not so straightforward. The Global North spent decades building with concrete before pivoting to more sustainable solutions, and now the same material is being regulated against in ways that disproportionately impact regions like Ghana, which are still building their infrastructure. That being said, I’m not looking to repeat the same mistakes by unconsciously making concrete buildings. We’re developing our own version of a low-carbon concrete mix and blending that with more sustainable systems, specifically for many of our multi-story projects. Until we get to the point where the technologies and knowledge are readily rampant in our regions, we have to start somewhere. This is my way of contributing to that start. I’m also super excited to finally have the Backyard Tennis Club open to the local community. It’s been a long time coming and they’ve been getting excited, seeing the towering panels erected in their neighbourhood.

People waiting to see your building?! You sound like a pop star. Did you ever imagine that?

I didn’t! But it’s a really beautiful, rewarding, and wholesome feeling that speaks to how integral we are within this community and how much they are a part of what we’re doing.

Surf Ghana, Busua, Ghana. Image courtesy of Surf Ghana.