Portrait of Frida Escobedo by Daniel Shea for PIN–UP 39. In partnership with Burberry.

Portrait of Frida Escobedo by Daniel Shea for PIN–UP 39. In partnership with Burberry.

Frida Escobedo is most comfortable living between two places. Raised by divorced parents, she remembers a childhood in transit, crossing parks and streets between their Mexico City homes. Today her commute is longer, from CDMX to Gotham, since the architect now runs offices in both her hometown and New York City. This penchant for the liminal finds expression in her buildings, which blur the line between private and public with projects that include the 2018 Serpentine Pavilion (at the time, Escobedo was the youngest architect to have received this honor), La Tallera museum and cultural center in Cuernavaca (2010–12), and boutique retail and hospitality concepts across North America and Mexico. She’s also juggling two major commissions set to be completed in 2030: an interior redesign of Paris’s mythic Centre Pompidou (led by Moreau Kusunoki) and construction of the new Tang Wing at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the first time a female architect has added to the storied uptown establishment. With key institutional jobs like these, it’s easy to forget Escobedo is as invested in ideas about the home as she is in the public realm, something she’s putting to the test in the contentious world of New York real estate with Ray Harlem, a 21-story mixed-use tower containing affordable housing and the new National Black Theatre (in collaboration with Handel Architects), as well as the exterior of a Brooklyn condominium that integrates public gathering space at street level (in partnership with DXA and Workstead). Her 2019 publication Domestic Orbits offers a counter-history of modern architecture in Mexico City, examining how iconic buildings concealed domestic labor, from the service quarters embedded in Luis Barragán’s own home to the cramped ancillary housing tucked behind the luxury residences in the affluent Polanco neighborhood. Furniture, for now, is her most personally expressive side project — think Screen 01 (2019), her sleek, mirrored room divider, or the elegant, draped nickel ball chain of her Creek chair and bench (2022). For the first conversation of this issue, PIN–UP invited the irreverent Sam Chermayeff —architect and longtime friend of Escobedo’s, and someone equally invested in challenging the norms of domesticity — to join her in discussing their shared views on lifestyle, why privacy might be overrated, and the ideal sofa.

In 2022, the Metropolitan Museum of Art commissioned Frida Escobedo for the renovation and expansion of its Oscar L. Tang and H.M. Agnes Hsu-Tang Wing, making her the first woman in the institution’s history to design a wing. The five-floor limestone renovation will expand gallery space for modern and contemporary art by 50 percent and is expected to be completed in 2030. © Filippo Bolognese Images

Felix Burrichter: Let’s start at the beginning. How did you two meet?

Frida Escobedo: I think it was when I visited the Moriyama House in Tokyo [Ryue Nishizawa, 2005]. That’s where you lived.

Sam Chermayeff: Yes, we met in my home! A long time ago. I was working for SANAA, where I stayed until 2010.

FE: It was the first time I saw this typology of a fragmented house. Sam gave us a tour, and it was so interesting how Sam described each of the spaces, and how it was more like a constellation, which was very different from the Mexican experience I had known until then. In Mexico, a large part of the population lives with extended family in the same household — grandmothers, aunts, cousins, brothers who are married, etc. And with the Moriyama House, it seemed like just the opposite. It was very singular, but also very expansive in a city that’s so dense. That’s a good question to consider: how do you build a different type of housing in a different culture? It’s one thing to design within your own culture, because the way we live is so embedded. What does it mean to do it outside of your home country?

FB: This makes me think of the Ordos 100 project, when in 2007 Ai Weiwei and Herzog & de Meuron invited 100 young architecture firms to a remote part of northern China to design a series of villas. Frida, you were part of it.

FE: Yes. It was a very interesting experiment in trying to shape the paradigm of the home. We all went — it was an incredible experience.

FB: In the end, none of the houses got built — someone once called it the Fyre Festival of architecture, but with a far more

interesting speculative outcome.

SC: Ordos 100 was a real thing that had real importance. I’m jealous you got to be part of that, Frida. It was the kind of gathering that doesn’t happen very often. It shaped a whole generation of architects.

Portrait of Frida Escobedo by Daniel Shea for PIN–UP 39. In partnership with Burberry.

Portrait of Frida Escobedo by Daniel Shea for PIN–UP 39. In partnership with Burberry.

FB: There is this saying that when you’re in a relationship with someone, you’re also in a relationship with their childhood. Frida, you grew up in Mexico City, and Sam, you grew up in Manhattan. To what extent did your childhood experiences shape your view of domestic space today?

SC: If you look past the conventional signifiers of privilege that come with an apartment on Manhattan’s Upper East Side, you’ll realize that the way my family lived was remarkably similar to the work I do. Like me now, my parents also lived far away from their parents and family, even my older siblings, so they were always looking for community, through hosting or social gatherings, creating some kind of domestic culture. They had people over all the time! This idea of extended family is something that everybody needs, and it’s also at the core of the building I live in right now [the Baugruppe Kurfürstenstraße 142, Berlin, completed by June 14 Meyer-Grohbrügge & Chermayeff in 2022]. One of the main reasons people are attracted to the Baugruppe is the relationship between neighbors, the way they are connected both socially and spatially through stacked apartment units. Even though it’s sometimes complicated and people still get upset with each other — and they constantly get upset with me about delivery boxes or late-night barbecues — residents in this building are here to be around other people, whether to help take care of their kids or for when they get old. I don’t want to take unnecessary credit, but these relationships are also, on some level, a result of the architecture. So, Frida, what you described in Mexico — people living with their extended family — that’s a real architectural quality!

FE: My upbringing was completely different. I was an only child, and my parents divorced when I was five. Afterwards, they lived in different apartments, and I would go back and forth a lot. My father was very active in my childhood — he basically spent every afternoon with me. They tried to live as close to each other as they could, so I could commute more easily. Most of my childhood memories are not necessarily from within their homes, but from those moments in transit, and what happened in between. Crossing the park to go to the other home — that was my playground. I believe that really shaped the way I think. I mean, I still live in two places — Mexico City and New York — and for a long time I didn’t realize my idea of being comfortable is moving between two cities, because it feels very natural to me. I actually get a little bit claustrophobic when I stay in one place too long. [Laughs.] My parents not living together also made me notice other social conventions. When I would invite friends or cousins over to my dad’s, they would be surprised that he was cooking or knitting my sweater, which was not the norm in Mexico at the time. That helped me understand how spaces are highly gendered. Take Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera’s house: they lived in separate wings, but there was only one kitchen, in Frida’s part of the building. You can have separate living spaces, but someone always needs to take care of people. And in my case, both parents could take care of me.

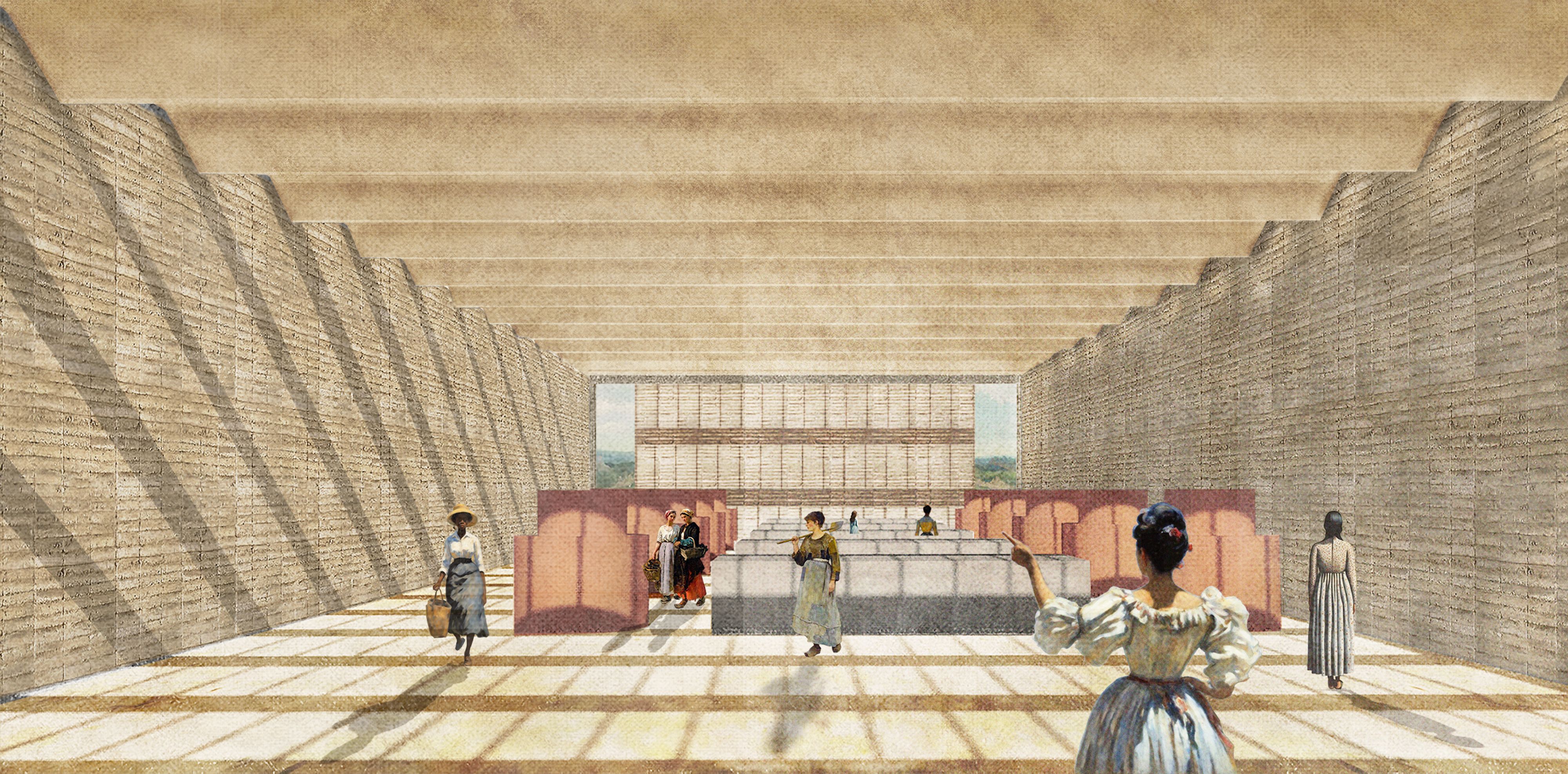

Organic mezcal brand YOLA MEZCAL commissioned Escobedo to design a new distillery in Oaxaca, Mexico, centered on the factory’s mostly female workforce. The zero-waste facility will be built with custom clay bricks made from agave waste (developed by COAA and Gnanli Landrou) and will include communal kitchens, gardens, and childcare. Courtesy Frida Escobedo Studio.

FB: So, a very different situation from the extended-family living you mentioned earlier.

FE: Yes. In Mexico, extended families live together to support childcare, elderly care, and to share expenses. It’s fascinating because domestic space really tells an economic story. If you’re lucky enough, you can choose how you want to live. There are also people who are displaced by war or by the need to find work. It’s interesting to consider how cities are shaped by these forces of displacement. For example, it’s easy to think everyone in New York is there by choice, but that’s not necessarily the case for the whole layer of people in the service industry or those who are caretakers. Those people may well be living in similar conditions to these shared Mexican homes, pooling some of the expenses. I think we should acknowledge that combination and that different typologies should emerge, not just for the real-estate developer, but for the actual needs of these underrecognized inhabitants.

FB: You each, in your own way, critique domestic norms, whether by questioning gendered spaces or challenging traditional bourgeois ideas of comfort. Sam, when did you first start actively rethinking domesticity?

SC: My mother didn’t want to cook on principle because of how gendered it was, and my father also went around like a classic 20th-century man and never cooked anyway, so we went out for dinner constantly. I literally didn’t boil pasta myself until after I left Tokyo, about 15 years ago. It took me a long time to realize that that doesn’t work. You’ve got to cook. Now I spend half my days designing kitchens, but this idea of challenging domestic norms came to me when I was living in the Moriyama House. I realized I didn’t care about privacy so much. I don’t mind if my neighbor sees me naked. I don’t care if they can hear me having sex. I don’t particularly need quiet alone time. And then I started asking myself, “Why does anyone? Where do those ideas come from?” I realized they came from industrialization and Modernist ideas, where people’s free time was reduced to a brief moment after work. Why people want efficiency or privacy gets you back to what they really want, which is connection, because they don’t have their families around. And then you realize people are willing to explore so many assumptions that developers aren’t. Developers, by default, are playing to the lowest common denominator of possible needs, so you end up with enclosed kitchens and various versions of privacy, internally and externally. I just realized, well, people didn’t ask for that, and it makes them feel isolated, and we can actually sell them a more communal proposition.

FE: The idea of privacy versus individuality is interesting to me. You ask if privacy is overrated, whereas for me, individuality is overrated, because we need to create connections. It feels like what you’re describing, Sam, is that developers are focusing more on designing out of fear of complaints or lawsuits, and for exchange value — if people are just passing through spaces, it creates more added value versus creating a home where people might stay for generations. The latter is probably not a good business model. But I would like to design a home where people would stay forever. If you live in a different, more collective typology, you’re able to create more connections. Then you might consume less because, when you’re lonely, you go out and consume, whether that’s social media, online shopping, whatever. Even a very basic thing like boiling pasta — cooking it for one person uses much more energy than cooking it collectively. Why don’t we simplify our lives a little bit more? That would maybe take the form of doing more things in smaller groups. I’m not saying this should be the case on a large scale, but maybe small groups would make things better for everyone.

Kitchen and interior patio of Mar Tirreno (2018), a discreet residential development in Escobedo’s hometown, Mexico City. Inspired by the morphology of the vecindad, typical early-20th-century Mexican multifamily apartment dwellings, the ten units feature small patios that serve as transitional spaces between the bustling street and the family homes. ©Rafael Gamo

A view of a private alley in Mar Tirreno. ©Rafael Gamo

A view framing the entrance to circulation serving the residential units of Mar Tirrenio. ©Rafael Gamo

FB: Let’s talk about the pinnacle of domestic comfort: the sofa. Speaking for myself, I have a fraught relationship with it. Frida, you haven’t designed one, but you’ve designed a bench draped in nickel-ball chain. Sam, you’ve tried your hand at the sofa typology. What are your thoughts on this staple of nearly every home?

FE: It’s so hard to find a nice sofa. I live in a very old Mario Pani building, and I recently had to change the windows in my apartment, which meant moving some of the furniture. I ended up with my futon in the middle of the living room, which turned out to be the most comfortable, wonderful thing. My partner and I would lie on the futon all day. And when people come over, they just lie comfortably on the carpet. I think the sofa is a social construct. It can feel very formal when it should be the most comfortable, relaxed thing. Sitting up straight on sofas harks back to an old idea of receiving guests and the ceremony that goes with that.

SC: The heavy-light thing about sofas is really an architectural problem. All the sofas I think are nice are the lightest-looking ones. My favorite sofa is by Franz West because it looks like you can pick it up and move it. It looks light enough to be body-related. My own sofa is comfy enough, but I will always trade comfort for lightness. With all of these design objects, I want to be able to see around them. I never put things up against the walls. I don’t have built-in closets. I have an obsession with seeing under things or seeing the wall behind them. We just made a sofa that’s really heavy-looking, and I keep wondering if we should make it lighter. It’s all too grand. It’s such an object. How do we do it with less?

FE: A sofa should be grounded, almost part of the surface. I don’t want it to be a thing. The sofa should just be like sitting on the beach.

SC: I follow that. I miss built-in sofas. The kind my grandfather did [the architect Serge Chermayeff, 1900–96] or all those other Modernists who just did built-in benches with up-holstered pillows. That was good. I would love to do a 70s interior where everything’s matching and built in — one giant carpeted sofa pit.

FB: I consider you both domestic anthropologists. Do you agree?

SC: Sure, Felix. [Laughs.]

FE: If you’re not curious about how people behave in space, maybe you’re not really an architect. I wouldn’t separate it. There’s no need to change the name of the profession.

Portrait of Frida Escobedo by Daniel Shea for PIN–UP 39. In partnership with Burberry.

FB: You’ve both worked on residential projects in very different cultural contexts. For you, Frida, Mexico City and the U.S., and for you, Sam, Berlin, the U.S., and the Albanian capital Tirana. How do you think about domestic space in these very different places, where social norms and building codes may prevent you from transposing your own inclinations?

SC: Albania is fascinating because they had a particularly rough form of communism in the 20th century — a hardcore, deep collectivization of everything. So when I talk to them about the notion of the collective building, they look at me like I’m out of my mind. They understand when I talk about actual public space, but in the individual, domestic unit, they want every feature — their own car, guest toilets with bidets in tiny apartments. There’s a very individualistic notion of freedom that’s quite troubling. I’m super sympathetic to that because these clients grew up in a time when everything was owned by the state — everything was somebody else’s, nothing was yours. I’m constantly trying to convince people to have semi-public space. There’s going to be a big public restaurant on the 23rd floor of the building we’re constructing in Tirana. I wonder if people will go to be together. But Frida, to go back to your comment about individualism — it reminded me of this funny thing about design journalism right now, which is how everything became a fucking home story. Basically, architecture doesn’t exist anymore as a thing to look at. The entire built world is reduced to the interior of the home, and I think the reason why has to do with this question of individualism. As consumers of architecture, we feel we have less and less agency. Everybody needs some way to define themselves, and I don’t know how we deal with that as architects, because I don’t think you can say that we should just go in favor of the collective. I want to fight with you on that.

FE: It’s not that I’m in favor of the collective being embedded in every single aspect of everything we design. Your building in Tirana brings up the concept of amenities, which fascinates me. Why would you have to have everything in the same building? On the one hand, having amenities is a question of privilege, but on the other, for people who are commuting long distances to get from their homes to their jobs, they actually need to have things that are closer to them. Maybe for specific housing units it’s actually more convenient to have a kindergarten, a little shop, an open area where people can exercise, and a playground all included within the same compound — that’s fine. But when we’re trying to make it a commodity, like with membership clubs, I think it’s problematic.

One of three large-scale projects currently underway in New York City, Ray Harlem is a multi-family apartment building by Frida Escobedo Studio with Handel Architects and interiors by Little Wing Lee and Ray’s in-house design team. The 21-story tower, which opened in June 2025, contains 222 residences, behind a façade of locally sourced brick arranged in patterned, layered compositions. Also housed within the tower is the National Black Theatre, founded in Harlem in 1968 by Dr. Barbara Ann Teer and now led by her daughter, Sade Lythcott, with reopening slated for 2026. © Melanie Landsman

Models and material testing for the design of Ray Harlem. Courtesy Frida Escobedo Studio.

SC: It’s a thin line between amenity and public. Private membership clubs are evil. In a lot of projects, I’m influenced by New York, where there’s ground-floor retail everywhere. There’s always a bodega downstairs where the person who runs it knows your name. Bringing that somewhere else is very hard. You’re pointing in the direction of the community that needs to be made somewhere between suburbia and the city center. In New York, as people move further and further out, the original suburbs are becoming working-class neighborhoods again, but they lack community, because they’re sort of disparate and have a strange density that makes it very difficult to sustain certain kinds of businesses.

FE: For me, it’s almost more about the question of private property. You were describing how some of your clients want to have everything within their home — it’s almost like a security blanket, the more features the better. I want to move away from that scheme to one where people could have a more compact footprint, where there’s value in the proximity of things around you that you don’t own, that you encounter in between — I think that would be the most efficient way of living. These spaces don’t belong to anyone, neither a corporation nor an individual. It’s this shared public space. I know that sounds like a fantasy, but it’s possible.

A detail of Bergen Brooklyn, a residential project in Boerum Hill. Here Escobedo drew on the local brownstone vernacular, translating it into a 400-foot-long undulating brick façade that creates private outdoor gardens for 75 percent of the units. Courtesy Frida Escobedo Studio.

A collage of Bergen Brooklyn's private outdoor gardens. Escobedo's collages eschew photorealism in favor of textural atmospheres, populated by figures from oil paintings and text books, to conjure a dreamlike effect open to imagination. Courtesy Frida Escobedo Studio.

FB: I want to talk about furniture. Sam, I did a conservative count — you’ve designed more than a dozen kitchens. And you’ve both designed objects and furniture. What’s your relationship to the design object individually, but also in the context of the domestic ritual?

FE: I’m fascinated, Sam, how you convince people to adopt such radical ideas, because I haven’t been able to. [Laughs.] What’s the trick to experimenting in such a way with kitchens, beds, and all of these things?

SC: I mean, particularly with Germans, it’s very easy. You just go on and on about how well it works. You say, “Well, it’s not that radical. There’s nothing weird about a triangular bed at all. A bed is a bed. Don’t worry about it.” I also remind people that they didn’t call me because they wanted the easy way out. It’s about ritualizing the domestic function. Ritualizing it doesn’t mean making it faster. It means making it better. Most stoves face walls for obvious reasons, unless you live in a huge suburban house with a big kitchen island. I want to propose, in a small space, how you can avoid facing the wall when you cook. It’s almost like, “Hey, this thing that you’re going to do anyway — now you don’t face the wall.” That’s almost the end of my pitch. By not facing the wall, you actually face your husband, your wife, your kids, your guests — that I figured out over time. This week, my obsession is big bowls. I want to make platters that are communal — too big for two people. At least three people have to use them. That changes everything. It’s the same with the bed, in a way — it suggests something bigger than yourself. And people are game for that suggestion. People aspire to be weirder than they are.

FE: It’s harder here in Mexico because people tend to have more conservative ways of thinking about domestic space. They want to have the standard, the traditional, they’re less open to other possibilities. With the furniture I design, I’m not trying to make things better or more functional, it’s more about pure aesthetic pleasure. When my dad sits in my chairs, he always complains they’re the most uncomfortable. [Laughs.] They’re very selfish, in a way, because I’m not thinking about designing these objects or pieces of furniture for other people, necessarily. It’s always just something I would like to explore, or something I would like to have, touch, or interact with. And then you just make it. If someone else wants it, great.

Portrait of Frida Escobedo by Daniel Shea for PIN–UP 39. In partnership with Burberry.

SC: All that I actually do with design objects is change the sizes to make them domestic. Domestic things, by nature, automatically have something to do with the body, with human scale. When you put together many of the objects that I think are good, including that screen of yours, Frida, they become almost like a little animal farm — these creatures, where some are taller and skinnier, some shorter and fatter. They suddenly become more like pets.

FE: Right, individual pieces have specific personalities, which I think is a very different concept from trying to create a homogeneous furniture arrangement where everything blends into the landscape of the home. There’s prescription and there’s playfulness — you can replace one object and still have the same feeling, versus the idea of interiors, generally, where everything is just perfect and nothing can move.

SC: I think that’s also a function of the transience you were mentioning, where homes are designed for turnover. Your notion that everybody should live in a home for the longest possible time is so attractive — I would design totally differently if that were the case. Because people need to move, I don’t make anything that doesn’t fit in an elevator anymore.

Escobedo’s forays into furniture and functional objects include Screen 01 (2019), a three-part divider playing on the voyeurism of blinds, windows, and mirrors, photographed at OMR gallery in Mexico City. Courtesy Frida Escobedo Studio.

Cube 01 (2025), a polished stainless-steel assemblage by Frida Escobedo. Courtesy Frida Escobedo Studio.

FB: What I’m trying to get at is the idea of voyeurism. Sam, you mentioned earlier enjoying the absence of privacy, while Frida, you once shared a childhood memory of gazing at apartment buildings and imagining the different lives behind the windows. How do these concepts of privacy, interior spaces, and external perception shape your work?

FE: I do feel I’m a little bit voyeuristic. The first time I encountered that was a moment of boredom, which is something I think we’re losing very quickly. We don’t get bored anymore because we’re constantly stimulated, and therefore we don’t observe anymore. I love the idea of being able to connect with people just by looking at them in their spaces, learning how they dress and move around. It’s almost like getting into the depth of their personality before even speaking to them. People are increasingly voyeuristic, but from a very artificial standpoint. We know what everyone is doing all the time through social media. We’re looking at people’s private lives constantly, but actually that’s not their real life. But looking through someone’s window — that’s reality versus a curated version of it. I think observing is a way of listening. Whether you’re designing a private home or a collective building, you need to start paying attention very early on to people’s gestures, behaviors, and references, before you start on your design. But if you’re designing a large family block, you don’t know who your final client is going to be. You can only sense what’s happening in the neighborhood, and you have to be very observant of that. It’s about being able to read the symbols, and quickly. It’s an exercise. You have to keep doing it every day.

SC: Absolutely. And obviously, I share that fascination. I invite myself to other people’s houses quite regularly. I even do this thing where I cook at other people’s places just to figure out how they live. I have to resist telling people they should get a new colander, or whatever. Somehow people get weirder and more individual in cities. The more jammed together they are, and the more similar the exteriors are, like with the East German Plattenbau, the more people want to express themselves within them. I’m more fascinated by people’s little expressions than my own. I often think of architecture as this universal thing in a Modernist kind of way, and then it’s so fascinating and warm to me how that universalism is individualized. Understanding that balance feels like the key to a lot of things.

30 Otis Plaza in San Francisco (2024), designed by Frida Escobedo Studio and Fletcher Studio with support from Multistudio, merges the civic and the intimate: a carved topography redirects pedestrian flow, while a crater-like center morphs into forum, fountain, or stage, according to the public’s needs. Mist diffusers and soft lighting evoke the city’s fog, making the plaza both refuge and spectacle. © Rory Gardiner

FB: I’d love to ask about your teaching experiences. Frida, you’ve taught at Harvard, Columbia, and the Architectural Association in London. Sam, you’re committed for another four years at the University of Applied Arts in Vienna. How do you balance the responsibility you feel to your clients, creating spaces for both individuals and the public, with the social responsibility you have towards your students?

FE: When I’m teaching studio, I’m not there to teach students how to design. That’s something they’ll figure out on their own. My responsibility is to have critical conversations with them and ask questions, because academia might be the only place in an architect’s life where they can actually ask these questions. So that’s a responsibility — being aware that there needs to be this space for questioning what we’re doing professionally all the time.

SC: My question to my students is: “How can we live differently?” I spend a huge amount of time just convincing them that we can. I promise, people will buy a triangular bed. Things change. The world changes. People feel like they can’t do anything and that they should just squirrel away and make careful, tiny things. You can sometimes think the whole world is conservative and it’s all going to shit, which it is. We did this thing where we turned the heat off in the Vienna studio for a month, just to fuck around. It was pretty cold. We wore sweaters. It was just to see: How hot do you need it to be? Where do we get this idea that everywhere has to be 70 degrees all the time? Just put a thicker sweater on. I didn’t personally mind because I was talking the whole time — I wasn’t laboring late at night, making models with cold fingers. But the point stands — what can we take? The world can take a lot. The second question is, what can you take? People can take a lot. People can change. It’s that simple.

Portrait of Frida Escobedo by Daniel Shea for PIN–UP 39. In partnership with Burberry.