Faye Toogood, Tiddlybits, from her rug collection for cc-tapis, 2024; hand-knotted 100 percent wool. Image courtesy Faye Toogood.

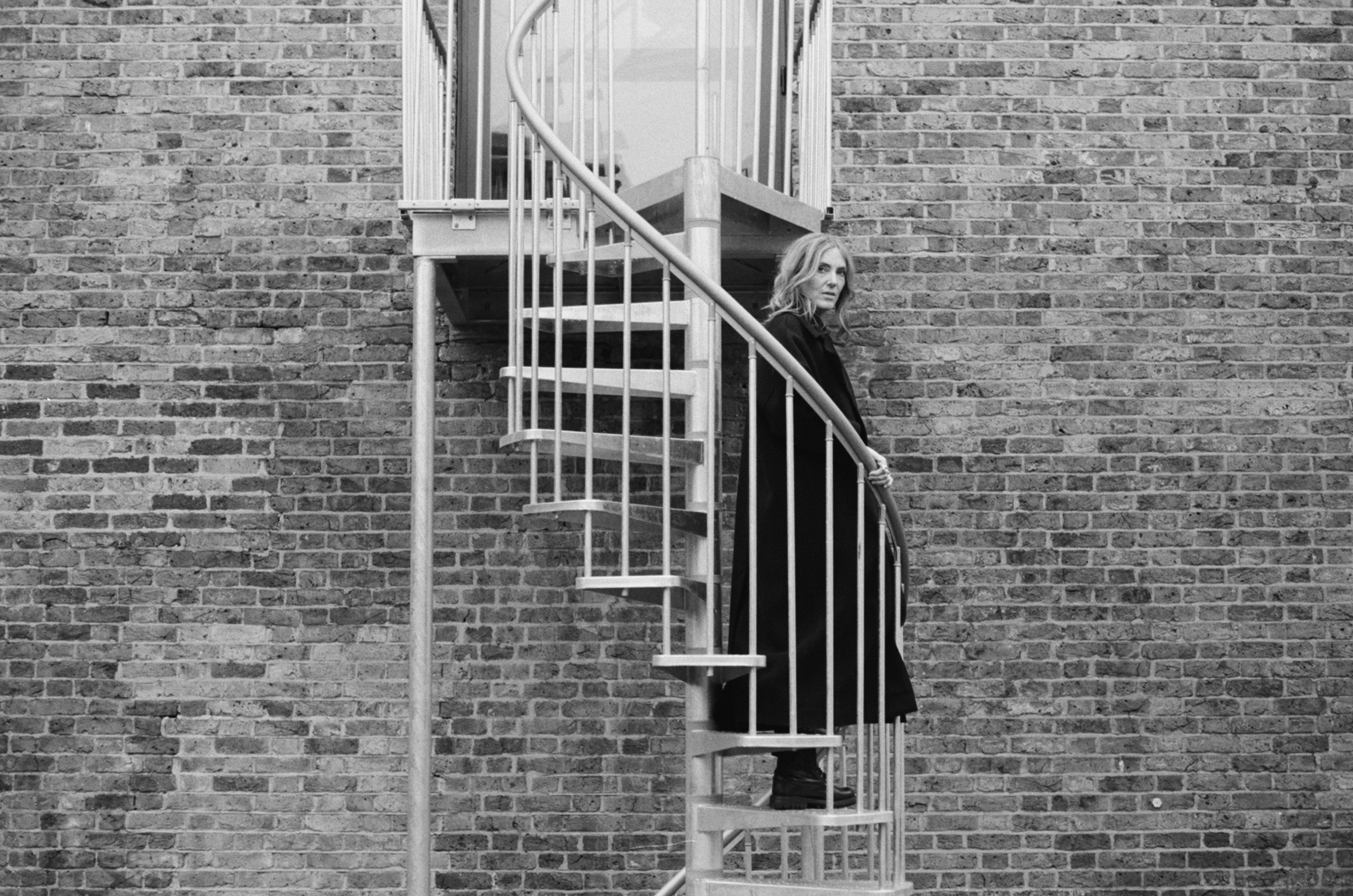

Faye Toogood photographed by Chiara Gabellini for PIN–UP 38.

Is what distinguishes the “creative disciplines” from one another — painting from architecture, music from filmmaking, and so on — a matter of scale, not medium? Putting things in terms of scale, as opposed to type, gives the attempt to differentiate such blurry boundaries an aspect that is quantifiable, concrete, numerical. Note that “scale” could mean a number of things: the size of the object, the size of its audience, the girth of its budget, or the height of its ambition. People who make buildings work at the “big” end of scale, but so do people who make small things — lamps, stools, leather goods, sweatpants — with global distribution, or even just high price points. There are, in other words, a lot of ways to be big. Scope of engagement is also one, and it’s among the reasons why Faye Toogood is, without any doubt, a very “big” designer. She started her creative-industry career at Condé Nast, working as an editor at World of Interiors under the maverick, I’ll-do-as-I-please eclecticism of founding editor Min Hogg. After eight years of handling unusual objects in unusual homes, she decided it was time to make things of her own: she founded Studio Toogood in London in 2008, oscillating between interior design, creative direction, furniture, and fashion (together with her sister Erica Toogood). By 2014 she had rolled out the Roly-Poly, a cheeky, short king of a chair that has become a 21st-century design icon. Since then, there have been collaborations with Carhartt, Birkenstock, Hermès, Hem, Tacchini, cc-tapis, and Poltrona Frau, to name but a few, plus the launch of the Toogood clothing line, gallery shows and museum retrospectives, and, recently, the 2025 Designer of the Year award at Paris’s Maison&Objet. Exaggerated, useful, silly, expensive, accessible, lofty, plush, cardboardy, and none of the above, Studio Toogood’s work is consistently large in vision, however small the production run, the object, or the number of destined users.

Faye Toogood, Squash armchair for Poltrona Frau, 2024; leather upholstery. Image courtesy Faye Toogood.

Victoria Camblin: You just got back from Paris, where you were named Designer of the Year. How does that make you feel?

Faye Toogood: Fantastic, actually! Ordinarily I’ve avoided labels like “designer” or “artist,” then suddenly being given that award made me think, “Does that make me a proper designer now?” It seems strange — and amazing!

We both come from an editorial background. I’ve found that the coolest part about being an editor in a cultural milieu is that you can pretty much talk about anything — you can call up a philosopher or an environmental scientist and put them in the magazine alongside the creatives.

Yes. And it’s similar to what I’m doing now. I realized that a couple of years ago: a team of people all working towards one goal, despite working on different things. I like that feeling. But it’s a difficult platform to explain to others. The only way I can describe it is that I inhabit the borders, the fringes, the corners — the places where others are not. For some, that makes me someone who is not serious about what I’m doing. But actually I go really deep into things on those fringes.

You’re comfortable there?

I think so. Because it’s where I feel more free. When you feel more free, you feel more creative. And that’s how I feel best, how I ground myself in the world.

What made you decide to leave World of Interiors and grow a design practice?

I didn’t study design, I studied fine art, but also history of art, which made me rigorous about research, about understanding the context of where we are and what’s come beforehand. That led me to World of Interiors, which was unlike anything else out there — in the magazine, a squat in south London, a mansion in Sweden, or a palace in Mali were all equally amazing examples of spaces. It was about the culture in which people were living. It was anthropological. And while I was there, I got to handle amazing antiques. That was my design education. But it wasn’t really about making. After eight years, I got to a point where I needed to get back to producing my own work, to working in three dimensions. With the magazine, you make something, then you wait two months, but when the piece comes out you don’t feel connected to it anymore.

Faye Toogood photographed by Chiara Gabellini for PIN–UP 38.

Faye Toogood, Tiddlybits, from her rug collection for cc-tapis, 2024; hand-knotted 100 percent wool. Image courtesy Faye Toogood.

Faye Toogood photographed by Chiara Gabellini for PIN–UP 38.

That’s true — there’s an alienation from the output in the time it takes your ideas to return to your desk as an object. And then it becomes this weird thing that you don’t want.

Exactly. You can’t look at it anymore. You’re already onto the next thing. You don’t have time to see someone reading your piece. So I felt there was a gap between making and experience that I needed to close. I was doing some work with Tom Dixon, Dover Street Market, and a few other clients — installation work, really — and at some point Dixon said to me, “I think you need to stop throwing things in the bin and start making permanent objects.”

He knew you were “throwing things in the bin?” And then gave you permission to stop?

He did. The other good bit of advice was from Ron Arad, who said, “Oh, it’s all in the geometry, Faye. It’s all in the geometry.” I put those two pieces of advice together and suddenly it made a lot of sense. I parked all the time I’d spent looking at antiques and decorative arts and World of Interiors and focused on geometry and shape. I even took color out of the question.

Sounds intimidating.

It was. I got dubbed a minimalist, but actually the rigor of only focusing on form and shape is what allowed me not to get overwhelmed by color or decoration — which, interestingly, are coming into my life again now. Once I felt I’d established the geometry, I was able to be excited about bringing them back into the work.

Is you work autobiographical?

In the sense that the work is balancing out what’s going on in my own life or in the world around me, yes. A bit like a barometer or a temperature gauge.

A scale, not a mirror.

It’s reflective, but not of myself. It’s reflective of what I’m feeling and seeing around me. If I’m feeling or seeing this, then I’ll balance it out in the work with that. I’ll provide the antidote.

Photographed by Chiara Gabellini for PIN–UP 38.

Photographed by Chiara Gabellini for PIN–UP 38.

Faye Toogood photographed by Chiara Gabellini for PIN–UP 38.

There are logistics involved in making objects — you need far more space, outlay, and materials than when making a magazine. How did you go about it?

It was that era when we were just beginning to use the Internet. When I started at World of Interiors, there was one computer in the corner of the room; eight years later, we all had them. I was working as a stylist on the side, so I put a website up. I realized I could just say that I was “doing interiors” on there. I mean, the work that I was getting was a bridge between interiors and styling, right? And I was getting paid well at the time for that. I invested all the money it earned into making objects, using the interiors and installations that I was doing for brands to pay for my own. That funded my first show.

In this post-multi-hyphenate era, do you feel you can actually have, or be seen as having, a rigorous practice in the “between” zones? Also, define “rigor” when we’re all expected to function as little one-person mini production studios.

Exactly. I don’t know if it’s any easier now than it was then. I doubt it. You can be accused of being a dilettante, just mixing and tampering and muddling along with things. I’ve always wanted to be serious. But I’ve never taken any outside investment. Everything we make gets put back into the next project. Honestly, the multidisciplinary nature of what I’ve done is what has ensured our survival. If we don’t have a strong interiors project, then we can’t make furniture or set up the clothing line. It’s an ecosystem.

One thing I find interesting about design, as opposed to contemporary art, for example, is the scale of production. If you make a lamp for Flos, they might produce thousands of them, and you have no idea what people are going to do with them.

And you have to be comfortable with that. I’ve realized that’s partly why I’m a designer, not an artist. When you create something as a designer, you’re only there for a fraction of its life. The interesting thing for me is what happens after it leaves the studio. Once it’s out, it’s out of your control. I get a buzz from that part, actually. You have to. Otherwise, you’d better go be an artist.

Have you ever been completely horrified seeing something you’ve designed somewhere?

Many times. I’ve also been horrified by all the replicas and repeats I’ve seen. Once a month someone sends me a picture of a really deformed version of the Roly-Poly. Now I find it kind of amusing.

Being bootlegged is definitely a milestone!

There are aspects of what I do that I do keep slightly pure. When you’re creating anything at volume, there are always things you can’t do, so making limited editions and artwork definitely still flexes a muscle for me. But mostly things have to be out there, living their own life. I find that with clothing in particular. I’ve never had the fashion designer’s desire to see people wearing the “full look.” We want people to take on their identity with the objects and the clothes we make, not enforce a dogmatic “Toogood” ethos.

The “full look” is the norm in magazines now. Can you imagine anyone telling a stylist not to mix brands when you were at World of Interiors?

I’ve been fascinated lately with this loss of identity, with the tendency in the industry toward homogeneity rather than identities that are changing and flowing. Technology and the way we use it, the way we communicate and get information, isn’t helping. We are all being forced into a single way of doing things. I grew up in an era that was so much about playing with identity — with designers like Westwood, with punk, new age, the New Romantics.

Faye Toogood, Puffy lounge chair for Hem, 2020; canvas upholstery in natural with stainless steel frame. Image courtesy Faye Toogood.

Faye Toogood photographed by Chiara Gabellini for PIN–UP 38.

With all the fashion labels out there, what was the impetus for starting a Toogood clothing line?

My sister had been working in the theater and doing couture work. As a pattern cutter, you’re very much in the back room. She was getting frustrated. I suggested we work on a project together. She came into the studio and we just started making things — she doesn’t really draw, either, we both go straight to making. She was able to create these amazing sculptures on the body just using flat cloth and a pair of scissors. It was a very liberating moment. I’d been working with steel and bronze — all these heavy materials that take so long to work with. Suddenly we were creating shapes on the body really quickly. We were looking for a uniform we could work in that made us feel like creatives, irrespective of age, gender, or size. It’s not heavily branded — it’s uniform-esque and utilitarian, but without being derivative of a particular moment in vintage French workwear, or whatever. We also had this desire to be playful and create something free. So we made the uniform on one side, and then on the other we created pieces that were hand-painted, more sculptural. Then we put a passport in the back: a giant label with the names of all the people involved in making each garment. The idea was that you would write your name on it too, and then when you passed it onto your partner, or your sister, or whoever, they could write theirs in as well. It gives it a sense of longevity, I guess. Also, it sounds mad, but when we started, twelve years ago, unisex clothing was still pretty radical. I remember doing all of these interviews where people would ask me about androgyny. But it wasn’t about androgyny, it was just about us. It’s pragmatic — you don’t need a different cut if it’s about functionality.

You make designs for you, but as a designer you’ve also got to make objects for other, bigger design companies, like Poltrona Frau, Driade, Tacchini, etc.

Up until a few years ago, I hadn’t worked with any large-scale furniture manufacturers. We did a Birkenstock collaboration that opened up a new way of thinking about production — we were faced with a level of manufacturing we’d never accessed before. As a designer, that’s hugely liberating. It got me thinking that I was ready to start working more often on a higher level of production. Producing in small quantities is expensive, which means the objects cost more. It’s fantastic to make products designed for more people.

Some of your best-known designs were collaborations, no? The Puffy lounge chair with Hem, for example.

Collaborations work best when they’re fully open, and when they’re with companies that are not already doing a version of what you’re doing. For example, when Poltrona Frau asked me to work with them, I didn’t get it at first — I couldn’t really see where I’d fit in aesthetically. Then you visit the factories, the archives, and the museum and you realize how much you can do. Some of what I saw in the Poltrona Frau back catalogue was just so avant-garde. They were really prepared to push it, to take a risk on something completely different.

You’re not just getting material production resources from these heritage brands, you’re also getting their archives.

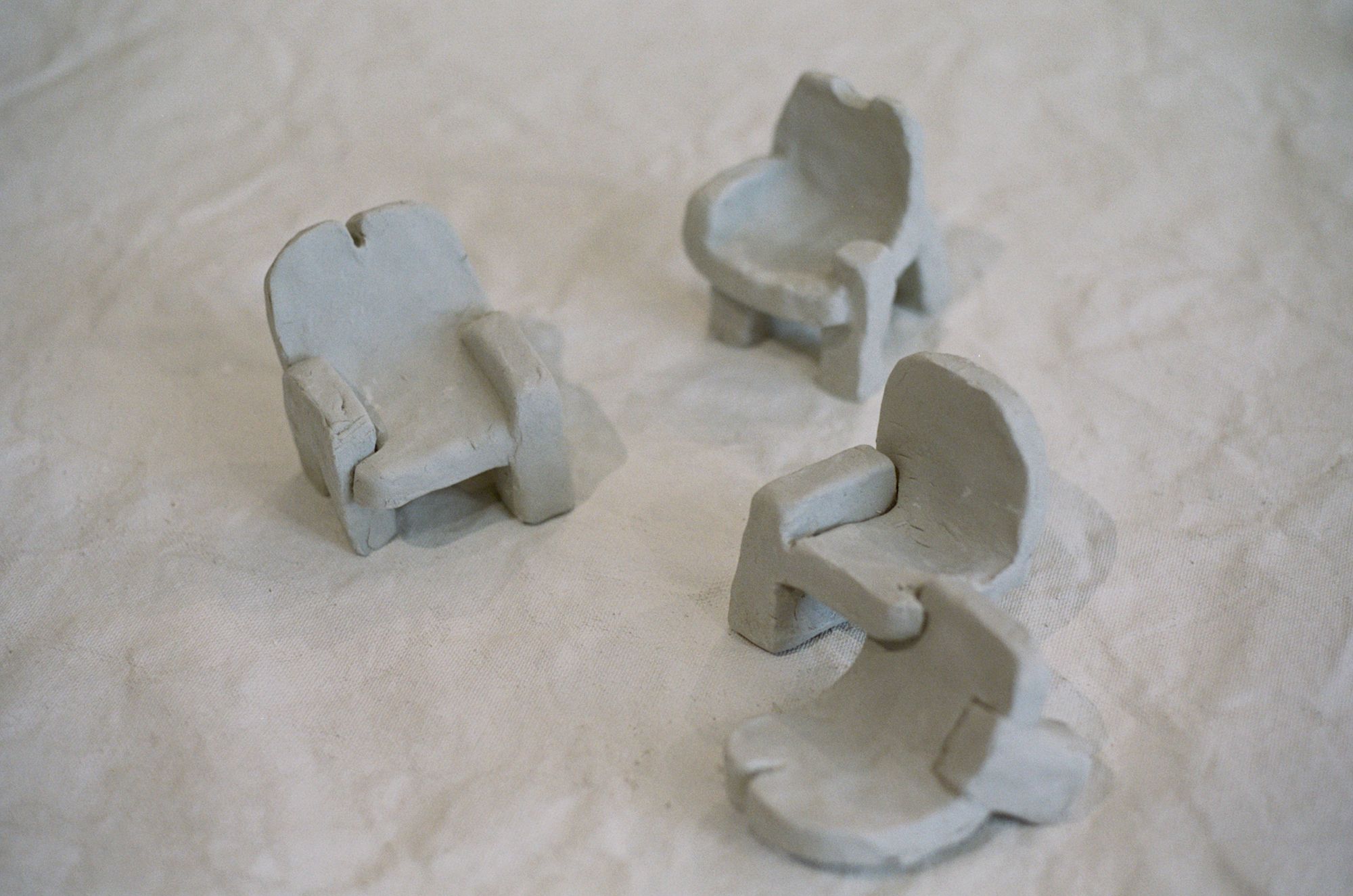

Which I love. I’m rather obsessive about saving everything as well — I’ve filled up vast amounts of storage. We have archival boxes everywhere in the studio. It comes down to an idea of revealing your process. Bringing in maquettes, showing models — these are ways of connecting with people through the piece, above and beyond the final object. A show called Assemblage 6: Unlearning that I did for Friedman Benda in 2020 completely changed my way of working in this respect. I had the feeling at the time that everything I was producing ended up looking too close to my own work or to the archives I was working with. In a bid to try to find my new language, my new vocabulary, I created hundreds of maquettes. Then I enlarged them to full scale, keeping the essence of the miniature. That resulted in chairs that looked like they were made of wire and card, but in fact were hand cast in bronze and painted to look like taped-up cardboard.

Faye Toogood, Roly-Poly chair, 2014; raw fiberglass. Image courtesy Faye Toogood.

Faye Toogood, Maquette 270 / Wire and Card chair, 2020; zinc-coated steel, cast aluminium, acrylic paint. Edition of eight. Exhibited at Assemblage 6: Unlearning at Friedman Benda in 2020. Image courtesy Faye Toogood.

Faye Toogood, Plot II, 2022; hand-carved Purbeck marble; Edition of eight. Exhibited at Assemblage 7: Lost and Found II at Friedman Benda in 2022. Image courtesy Faye Toogood.

Have you designed much with children in mind?

It’s funny, the other day I woke up and thought, “I need to do a children’s book.” I think the most successful creatives are those who have held onto certain aspects of childhood. I’m really fascinated with preserving imagination and creativity, which is based in play. That comes out as humor, or naivety, or maybe as an odd proportion of something “wrong” about the material.

Or as an object being used for something other than the function for which it was designed? I remember my parents had this big soap dish that I repurposed as a fabulous Barbie jacuzzi.

And that comes so naturally to children. It’s truly magic, and we really need it for innovation. In fact, if we don’t tap into that, innovation is at risk. We can have all the rigor and the research we want, but we’ll just be repeating one another if we don’t channel that organic sense of invention. Referencing only ourselves is deadly.

Do you live with your own designs at home? I feel like designers fall into two camps there, and I could see you going either way.

It’s a bit like fashion designers who can’t wear their own clothes. But I do. I wear the clothing. If I’m not going to wear it, how can I expect anybody else to? With the furniture and objects, it’s hard to live with your own work because you’re always very critical. But the reality is that I always get the prototypes, or pieces that didn’t quite make it, or samples, or things we made too many of, so it’s practical. And there are also a huge number of pieces I’ve made that I can’t even afford.

So you’re not living in your own showroom, in a controlled environment that encapsulates your output?

No. I would say it’s more like a funny portfolio or a kind of live sketchbook. Materials taught me that all good homes are a layering of things that you’ve been given, collected. Some things you like, some things you don’t; some things you’re trying to cover up, some things you’ve inherited. That’s what makes those spaces so much more interesting.

Photographed by Chiara Gabellini for PIN–UP 38.

Faye Toogood, Gummy armchair and footstool, 2024; upholstered in Pierre Frey Opio in kiwi. Image courtesy Faye Toogood.

Photographed by Chiara Gabellini for PIN–UP 38.

What’s your media consumption like these days?

I don’t have anything. I’m off Instagram. I don’t take any magazines.

Do you read fiction?

Rarely. I read a lot of nonfiction, and also poetry.

You mentioned children’s books. Why not design a children’s playground?

I would love to do a children’s playground. Or an educational environment. I have three children, but there’s a calling around “saving” childhood, essentially.

In interviews, do you get a lot of questions around your experience as a woman designer?

At the moment? Tons. And I spent many, many years refusing any interviews around my gender, but I’m prepared to talk about it now. Although plenty of publications have addressed women in design, the statistics haven’t changed, or maybe by one percent. That’s not enough. And we need more women in that environment.I won’t keep beating this drum — I’ll move on to other things. But I’m no longer shying away from being a woman in my work. I’m using words like “emotion” and “sensual,” areas I’ve held back on in order to be taken seriously or for fear of being judged. Maybe I’m just getting old now. I’m not going to hide anymore. And I have young girls and women writing messages and coming up to me after talks to say, “Thank you for calling it.” I would physically hide it in my work, removing color, decoration, textile, ceramics. Now, it’s all coming back, interestingly.

Interiors are also the domain of the woman, of domestic labor. The home versus the skyscraper. The square...

...and the circle. Hard and soft. I was working with squares that were hard, and now I’m working with circles that are soft and colorful. Fuck it.

Faye Toogood photographed by Chiara Gabellini for PIN–UP 38.

Faye Toogood, Solar daybed from the Cosmic collection for Tacchini, 2024. Image courtesy Faye Toogood.